A Rogue By Compulsion (9)

By:

May 24, 2016

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

My shopping took me quite a little while. There were a lot of things I wanted to get, and I saw no reason for hurrying — especially as McMurtrie was paying for the taxi. I stopped at Selfridge’s and laid in a small but nicely chosen supply of shirts, socks, collars, and other undergarments, and then, drifting slowly on, picked up at intervals some cigars, a couple of pairs of boots, and a presentable Homburg hat.

The question of a suit of clothes was the only problem that offered any real difficulties. Apart from the fact that Savaroff’s suit was by no means in its first youth, I had a strong objection to wearing his infernal things a moment longer than I could help. I was determined to have a decently cut suit as soon as possible, but I knew that it would be a week at least before any West End tailor would finish the job. In the meantime I wanted something to go on with, and in my extremity I suddenly remembered a place in Wardour Street where four or five years before I had once hired a costume for a Covent Garden ball.

I told the man to drive me there, and much to my relief found the shop still in existence. There was no difficulty about getting what I wanted. The proprietor had a large selection of what he called “West End Misfits,” amongst which were several tweeds and blue serge suits big enough even for my somewhat unreasonable proportions. I chose the two that fitted me best, and then bought a second-hand suit-case to pack them away in.

I had spent about fifteen pounds, which seemed to me as much as a fifty-pound capitalist had any right to squander on necessities. I therefore returned to the taxi and, arranging my parcels on the front seat, instructed the man to drive me down to the address that McMurtrie had given me.

Pimlico was a part of London that I had not patronized extensively in the days of my freedom, and I was rather in the dark about the precise situation of Edith Terrace. The taxi-man, however, seemed to suffer under no such handicap. He drove me straight to Victoria, and then, taking the road to the left of the station, turned off into a neighbourhood of dreary-looking streets and squares, all bearing a dismal aspect of having seen better days.

Edith Terrace was, if anything, slightly more depressing than the rest. It consisted of a double row of gaunt, untidy houses, from which most of the original stucco had long since peeled away. Quiet enough it certainly was, for along its whole length we passed only one man, who was standing under a street lamp, lighting a cigarette. He looked up as we went by, and for just one instant I had a clear view of his face. Except for a scar on the cheek he was curiously like one of the warders at Princetown, and for that reason I suppose this otherwise trifling incident fixed itself in my mind. It is funny on what queer chances one’s fate sometimes hangs.

We pulled up at Number 3 and, mounting some not very recently cleaned steps, I gave a brisk tug at a dilapidated bell-handle. After a minute I heard the sound of shuffling footsteps; then the door opened and a funny-looking little old woman stood blinking and peering at me from the threshold.

“How do you do?” I said cheerfully. “Are you Mrs. Oldbury?”

She gave a kind of spasmodic jerk, that may have been intended for a curtsey.

“Yes, sir,” she said. “I’m Mrs. Oldbury; and you’d be the gentleman I’m expectin’ — Dr. McMurtrie’s gentleman?”

This seemed an accurate if not altogether flattering description of me, so I nodded my head.

“That’s right,” I said. “I’m Mr. Nicholson.” Then, as the heavily laden taxi-man staggered up the steps, I added: “And these are my belongings.”

With another bob she turned round, and leading the way into the house opened a door on the right-hand side of the passage.

“This will be your sitting-room, sir,” she said, turning up the gas. “It’s a nice hairy room, and I give it a proper cleaning out this morning.”

I looked round, and saw that I was in a typical “ground-floor front,” with the usual cheap lace curtains, hideous wall paper, and slightly stuffy smell. At the back of the room, away from the window, were two folding doors.

My landlady shuffled across and pushed one of them open. “And this is the bedroom, sir. It’s what you might call ‘andy—and quiet too. You’ll find that a nice comfortable bed, sir. It’s the one my late ‘usband died in.”

“It sounds restful,” I said. Then walking to the doorway I paid off the taxi-man, who had deposited his numerous burdens and was waiting patiently for his fare.

As soon as he had gone, Mrs. Oldbury, who had meanwhile occupied herself in pulling down the blinds and drawing the curtains, inquired whether I should like anything to eat.

“I don’t think I’ll trouble you,” I said. “I have got to go out in any case.”

“Oh, it’s no trouble, sir — no trouble at all. I can put you on a nice little bit o’ steak as easy as anything if you ‘appen to fancy it.”

I shook my head. A few weeks ago “a nice little bit o’ steak” would have seemed like Heaven to me, but since then I had become more luxurious. I was determined that my first dinner in London should be worthy of the occasion. Besides, I had other business to attend to.

“No, thanks,” I said firmly. “I don’t want anything except some hot water and a latchkey, if you have such a thing to spare. I don’t know what time you go to bed here, but I may be a little late getting back.”

She fumbled in her pocket and produced a purse, from which she extricated the required article.

“I’m not gen’rally in bed — not much before midnight, sir,” she said. “If you should be later per’aps you’d be kind enough to turn out the gas in the ‘all. I’ll send you up some ‘ot water by the girl.”

She went off, closing the door behind her; and picking up my parcels and bags I carried them into the bedroom and started to unpack. I decided that the blue suit was most in keeping with my mood, so I laid this out on the bed together with a complete change of underclothes. I was eyeing the latter with some satisfaction, when there came a knock at the door, and in answer to my summons the “girl” entered with the hot water. She was the typical lodging-house drudge, a poor little object of about sixteen, with a dirty face and her hair twisted up in a knot at the back of her head.

“If yer please, sir,” she said, with a sniff, “Mrs. Oldbury wants ter know if yer’ll be likin’ a barf in the mornin’.”

“You can tell Mrs. Oldbury that the answer is yes,” I said gravely.

Then I paused. “What’s your name?” I asked.

She sniffed again, and looked at me with round, wondering eyes.

“Gertie, sir. Gertie ‘Uggins.”

I felt in my pocket and found a couple of half-crowns.

“Take these, Gertie,” I said, “and go and have a damned good dinner the first chance you get.”

She clasped the money in her grubby little hand.

“Thank you, sir,” she murmured awkwardly.

“You needn’t thank me, Gertie,” I said; “it was a purely selfish action. There are some emotions which have to be shared before they can be properly appreciated. My dinner tonight happens to be one of them.”

She shifted from one leg to the other. “Yes, sir,” she said. Then with a little giggle she turned and scuttled out of the room.

I washed and dressed myself slowly, revelling in the sensation of being once more in clean garments of my own. I was determined not to spoil my evening by allowing any bitter or unpleasant thoughts to disturb me until I had dined; after that, I reflected, it would be quite time enough to map out my dealings with George.

Lighting a cigarette I left the house, and set off at a leisurely pace along Edith Terrace. It was my intention to walk to Victoria, and then take a taxi from there to whatever restaurant I decided to dine at. The latter question was not a point to be determined lightly, and as I strolled along I debated pleasantly in my mind the attractions of two or three of my old haunts.

By the time I reached Victoria I had decided in favour of Gaultier’s — if Gaultier’s was still in existence. It was a place that, in my time at all events, had been chiefly frequented by artists and foreigners, but the food, of its kind, was as good there as anywhere in London.

I beckoned to a passing taxi, and waving his arm in response the driver swerved across the street and drew up at the kerb.

“Where to, guv’nor?” he inquired.

I gave him the direction, and then turned to open the door. As I did so I noticed a man standing on the pavement close beside me looking vacantly across the street. For an instant I wondered where I had seen him before; then quite suddenly I remembered. He was the man we had passed in Edith Terrace, lighting a cigarette under the street lamp — the man who had reminded me of one of the prison warders. I knew I was not mistaken because I could see the scar on his face.

With a sudden vague sense of uneasiness I got into the taxi and shut the door. The gentleman on the pavement paid no attention to me at all. He continued to stand there staring aimlessly at the traffic, until we had jerked forward and turned off round the corner of Victoria Street.

All the same the incident had left a kind of uncomfortable feeling behind it. I suppose an escaped convict is naturally inclined to be suspicious, and somehow or other I couldn’t shake off the impression that I was being watched and followed. If so, I had not much doubt whom I was indebted to for the honour. It had never seemed to me likely that McMurtrie would leave me entirely to my own sweet devices while I was in London — not, at all events, until he had satisfied himself that I had been speaking the truth about my intentions.

Still, even if my suspicions were right, there seemed no reason for being seriously worried. The gentleman on the pavement might have overheard me give the address to the driver, but that after all was exactly what I should have liked him to hear. Dinner at Gaultier’s sounded a most natural preliminary to an evening’s dissipation, and unless I was being actually followed to the restaurant I had nothing to fear. It was quite possible that my friend with the scar was only anxious to discover whether I was really setting out for the West End.

All the same I determined to be devilish careful about my future movements. If McMurtrie wanted a report he should have it, but I would take particular pains to see that it contained nothing which would in any way disturb his belief in me.

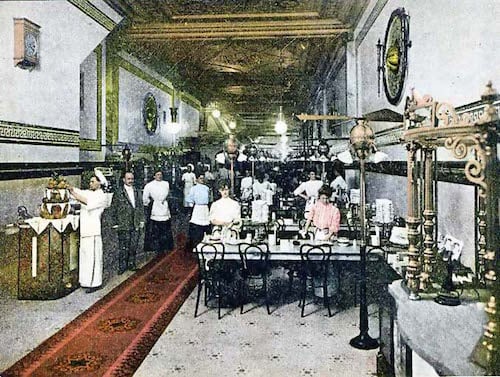

We pulled up at Gaultier’s, and I saw with a sort of sentimental pleasure that, outside at all events, it had not altered in the least during my three years’ exile. There was the same discreet-looking little window, the same big electric light over the door, and, unless I was much mistaken, the same uniformed porter standing on the mat.

When I entered I found M. Gaultier himself, as fat and bland as ever, presiding over the scene. He came forward, bowing low after his usual custom, and motioned me towards a vacant table in the corner. I felt an absurd inclination to slap him on the back and ask him how he had been getting on in my absence.

It seemed highly improbable that he would remember my voice, but, as I had no intention of running any unnecessary risks, I was careful to alter it a little when I spoke to him.

“Good-evening,” I began; “are you M. Gaultier?”

He bowed and beamed.

“Well, M. Gaultier,” I said, “I want a good dinner — a quite exceptionally good dinner. I have been waiting for it for some time.”

He regarded me keenly, with a mixture of sympathy and professional interest.

“Monsieur is hungry?” he inquired.

“Monsieur,” I replied, “is both hungry and greedy. You have full scope for your art.”

He straightened himself, and for an inspired moment gazed at the ceiling. Then he slapped his forehead.

“Monsieur,” he said, “with your permission I go to consult the chef.”

“Go,” I replied. “And Heaven attend your council.”

He hurried off, and I beckoned to the head waiter.

“Fetch me,” I said, “a Virginian cigarette and a sherry and bitters.”

A true gourmet would probably shudder at such a first course, but it must be remembered that for three years my taste had had no opportunity of becoming over-trained. Besides, in matters of this sort I always act on the principle that it’s better to enjoy oneself than to be artistically correct.

Lying back in my chair I looked out over the little restaurant with a sensation of beautiful complacency. The soft rose-shaded lamps threw a warm glamour over everything, and through the delicate blue spirals of my cigarette I could just see the laughing face of a charmingly pretty girl who was dining with an elderly man at the opposite table. I glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. It was close on eight—the hour when the cell lights at Princetown are turned out, and another dragging night of horror and darkness begins. Slowly and luxuriously I sipped my sherry and bitters.

I was aroused from my reverie by the approach of M. Gaultier, who carried a menu in his hand.

He handed me the card with another bow, and then stepped back as though to watch the result. This was the dinner:

Clear soup.

Grilled salmon.

Lamb. New potatoes.

Woodcock.

Pêche Melba.

Marrow on Toast.

I read it through, enjoying each separate word, and then, with a faint sigh, handed it back to him.

“Heaven,” I said, “was undoubtedly at the conference.”

M. Gaultier picked up a wine list from the table. “And what will Monsieur drink?” he inquired reverently.

“Monsieur,” I replied, “has perfect faith in your judgment. He will drink everything you choose to give him.”

Half an hour later I again lay back in my chair, and lapped in a superb contentment gently murmured to myself those two delightful lines of Sydney Smith’s —

“Serenely calm, the epicure may say:

Fate cannot harm me, I have dined today.”

I sipped my Turkish coffee, lighted the fragrant Cabana which M. Gaultier had selected for me, and debated cheerfully with myself what I should do next. I had had so many unpleasant evenings since my trial that I was determined that this one at all events should be a complete success.

My first impulse of course was to visit George. There was something very engaging in the thought of being ushered into his presence by a respectable butler, and making my excuses for having called at such an unreasonable hour. I pictured to myself how he would look as I gradually dropped my assumed voice, and very slowly the almost incredible truth began to dawn on him.

So charming was the idea that it was only with some reluctance I was able to abandon it. I didn’t want to waste George: he had to last me at least three days, and I felt that if I went down there now, warmed and exhilarated with wine and food, I should be almost certain to give myself away. I had no intention of doing that until the last possible moment. I still had a sort of faint irrational hope that by watching George without betraying my identity, I might discover something which would throw a little light on his behaviour to me.

But if I didn’t go to Cheyne Walk, what was I to do? I put the question to myself as I slowly lifted the glass of old brandy which the waiter had set down in front of me, and before the fine spirit touched my lips the answer had flashed into my mind. I would go and see Tommy!

It was the perfect solution of the difficulty; and as I put down the glass again I laughed softly in sheer happiness. The prospect of interviewing Tommy without his recognizing me was only a degree less attractive than the thought of a similar experience with George. I knew that the mere sight of his velvet coat and his dear old burly carcase would fill me with the most delightful emotions—emotions which now, amongst all my one-time friends, he and perhaps poor little Joyce would alone have the power to provoke. The others seemed to me as dead as the past to which they belonged.

One thing I was determined on, and that was that I wouldn’t give away my secret. It would be difficult not to, for there were naturally a hundred things I wanted to say to Tommy; but, however much I might be tempted, I was resolved to play the game. It was not the thought of my promise to McMurtrie (that sat very easily on my conscience), but the possibility of getting Tommy himself into trouble. I knew that for me he would run any risk in the world with the utmost cheerfulness, but I had no intention of letting him do it. He had done more than enough for me at the time of the trial.

I called for the waiter and paid my bill. It seemed absurdly cheap for such a delightful evening, and I said as much to M. Gaultier, who insisted on accompanying me to the door. He received the remark with a protesting gesture of his hands.

“Most people,” he said, “feed. Monsieur eats. To such we do not wish to overcharge. It is a pleasure to provide a dinner which is appreciated.”

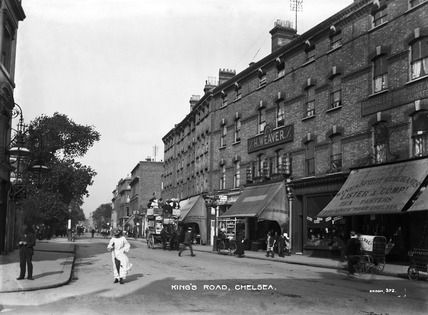

The porter outside volunteered to call me a taxi, and while he was engaged in that operation I had a sharp look up and down the street to see whether my friend with the scar was hanging about anywhere. I could discern no sign of him, but all the same, when the taxi came up, I took the precaution of directing the man in a fairly audible voice to drive me to the Pavilion, in Piccadilly Circus. It was not until we were within a few yards of that instructive institution that I whistled through the tube and told him to take me on to Chelsea.

I knew Tommy was in the same studio, for Joyce had told me so in her second letter. It was one of a fairly new block of four or five at the bottom of Beaufort Street, about half a mile along the embankment from George’s house. All the way down I was debating with myself what excuse I could offer for calling at such a late hour, and finally I decided that the best thing would be to pretend that I was a travelling American artist who had seen and admired some of Tommy’s work. Under such circumstances it would be difficult for the latter not to ask me in for a short chat.

I stopped the cab in the King’s Road, and getting out, had another good look round to see that I was not being followed. Satisfied on this point, I lighted a second cigar and started off down Beaufort Street.

The stretch of embankment at the bottom seemed to have altered very little since I had last seen it. One or two of the older houses had been done up, but Florence Court, the block of studios in which Tommy lived, was exactly as I remembered it. The front door was open, after the usual casual fashion that prevails in Chelsea, and I walked into the square stone hall, which was lighted by a flickering gas jet.

There was a board on the right, containing the addresses of the various tenants. Opposite No. 3 I saw the name of Mr. T.G. Morrison, and with a slight quickening of the pulse I advanced along the corridor to Tommy’s door.

As I reached it I saw that there was a card tied to the knocker. I knew that this was a favourite trick of Tommy’s when he was away, and with a sharp sense of disappointment I bent down to read what was written on it. With some difficulty, for the light was damnable, I made out the following words, roughly scribbled in pencil:

“Out of Town. Please leave any telegrams or urgent letters at No. 4.

T.M.”

I dropped the card and stood wondering what to do. If Tommy had some pal living next door, as seemed probable from his notice, the latter would most likely know what time he was expected to return. For a moment I hesitated: then retracing my steps, I walked back into the hall and glanced at the board to see who might be the tenant of No. 4.

To my surprise I found it was a woman — a “Miss Vivien.”

At first I thought I must be wrong, for women had always been the one agreeable feature of life for which Tommy had no manner of use. There it was, however, as plain as a pikestaff, and with a feeling of lively interest I turned back towards the flat. Whoever Miss Vivien might be, I was determined to have a look at her. I felt that the girl whom Tommy would leave in charge of his more important correspondence must be distinctly worth looking at.

I rang the bell, and after a short wait the door was opened by a little maid about the size and age of Gertie ‘Uggins, dressed in a cap and a print frock.

“Is Miss Vivien in?” I asked boldly.

She shook her head. “Miss Vivien’s out. ’Ave you got an appointment?”

“No,” I said. “I only want to know where Mr. Morrison is, and when he’s coming back. There’s a notice on his door asking that any letters or telegrams should be left here, so I thought Miss Vivien might know.”

She looked me up and down, with a faint air of suspicion.

“’E’s away in ’is boat,” she said shortly. “’E won’t be back not till Thursday.”

So Tommy still kept up his sailing! This at least was news, and news which had a rather special interest for me. I wondered whether the “boat” was the same little seven-tonner, the Betty, in which we had spent so many cheerful hours together off the Crouch and the Blackwater.

“Thanks,” I said; and then after a moment’s pause I added, “I suppose if I addressed a letter here it would be forwarded?”

“I s’pose so,” she admitted a little grudgingly.

There seemed to be nothing more to say, so bidding the damsel good-night, I walked off down the passage and out on to the embankment. If I had drawn a blank as far as seeing Tommy was concerned, my evening had not been altogether fruitless. I felt vastly curious as to who Miss Vivien might be. Somehow or other I couldn’t picture Tommy with a woman in his life. In the old days, partly from shyness and partly, I think, because they honestly bored him, he had always avoided girls with a determination that at times bordered on rudeness. And yet, unless all the signs were misleading, it was evident that he and his next-door neighbour were on fairly intimate terms. The most probable explanation seemed to me that she was some elderly lady artist who darned his socks for him, and shed tears in secret over the state of his wardrobe. There was a magnificent uncouthness about Tommy which would appeal irresistibly to a certain type of motherly woman.

I strolled up the embankment in the direction of Chelsea Bridge, smiling to myself over the idea. Whether it was right or not, it presented such a pleasing picture that I had walked several hundred yards before I quite woke up to my surroundings. Then with a sudden start I realized that I was quite close to George’s house.

It was a big red-brick affair, standing back from the embankment facing the river. As I came opposite I could see that there was a light on the first floor, in the room which I knew George used as a study. I stopped for a minute, leaning back against the low wall and staring up at the window.

I wondered what my cousin was doing. Perhaps he was sitting there, looking through the evening paper in the vain hope of finding news of my capture. I could almost see the lines on his forehead and the nervous, jerky way in which he would be biting his fingers—a trick of his that had always annoyed me intensely. He would bite harder than ever if he only knew that I was standing outside in the darkness not more than twenty yards away from him!

I waited for a little while in the hope that he might come to the window, but this luxury was denied me.

“Good-night, George,” I said softly; “we’ll meet in the morning,” and then, with a last affectionate look at the lighted blind, I continued my way along the embankment.

I was not sure which turning I ought to take for Edith Terrace, but an obliging policeman who was on duty outside the Tate Gallery put me on the right track. There was something delicately pleasing to my sense of humour in appealing to a constable, and altogether it was in a most contented frame of mind that I inserted my latch-key into Mrs. Oldbury’s door and let myself into the house. My first day’s holiday seemed to me to have been quite a success.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.