A Rogue By Compulsion (5)

By:

April 30, 2016

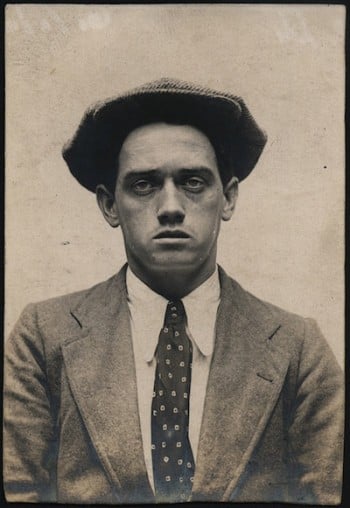

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

With a big effort I pulled myself together. “Come in,” I called out.

The door opened, and the girl, Sonia, entered the room. She was carrying a tray, which she set down on the top of the chest of drawers.

“I don’t know the least how to thank you for all this,” I said.

She turned round and looked at me curiously from under her dark eyebrows.

“For all what?” she asked.

“This,” I repeated, waving my hand towards the tray, “and the hot bath last night, and incidentally my life. If it hadn’t been for you and Dr. McMurtrie I think my ‘career,’ as the Daily Mail calls it, would be pretty well finished by now.”

She stood where she was, her hand on her hip, her eyes fixed on my face.

“Do you know why we are helping you?” she asked.

I shook my head. “I haven’t the faintest notion,” I answered frankly. “It certainly can’t be on account of the charm of my appearance. I’ve just been looking at myself in the glass.”

She shrugged her shoulders half impatiently. “What does a man’s appearance matter? You can’t expect to break out of Dartmoor in a frock-coat.”

“No,” I replied gravely; “there must always be a certain lack of dignity about such a proceeding. Still, when one looks like — well, like an escaped murderer, it’s all the more surprising that one should be so hospitably received.”

She picked up the tray again, and brought it to my bedside.

“Oh!” she said; “I shouldn’t build too much upon our hospitality if I were you.”

I took the tray from her hands. “I would build upon yours to any extent,” I said; “but I am under no illusion whatever about Dr. McMurtrie’s disinterestedness. He and your father — it is your father, isn’t it? — are coming up to explain matters as soon as I have had something to eat.”

She stood silent for a moment, her brows knitted in a frown.

“They mean you no harm,” she said at last, “as long as you will do what they want.” Then she paused. “Did you murder that man Marks?” she asked abruptly.

I swallowed down my first mouthful of fish. “No,” I said; “I only knocked him about a bit. He wasn’t worth murdering.”

She stared at me as if she was trying to read my thoughts.

“Is that true?” she said.

“Well,” I replied, “he was alive enough when I left him, judging from his language.”

“Then why did your partner — Mr. Marwood — why did he say that you had done it?”

“That,” I said softly, “is a little question which George and I have got to discuss together some day.”

She walked to the door and then turned.

“If a man I had trusted and worked with behaved like that to me,” she said slowly, “I should kill him.”

I nodded my approval of the sentiment. “I daresay it will come to that,” I said; “the only thing is one gets rather tired of being sentenced to death.”

She gave me another long, curious glance out of those dark brown eyes of hers, and then going out, closed the door behind her.

For an exceedingly busy and agreeable quarter of an hour I occupied myself with the contents of the tray. There was some very nicely grilled whiting, a really fresh boiled egg, a jar of honey, and a large plate of brown bread and butter cut in sturdy slices. Best of all, on the edge of the tray were a couple of McMurtrie’s cigarettes. Whether he or Sonia was responsible for this last attention I could not say. I hoped it was Sonia: somehow or other I did not want to be too much indebted to Dr. McMurtrie.

I finished my meal — finished it in the most complete sense of the phrase — and then, putting down my tray on the floor, reverently lighted up. I found that my first essay in smoking on the previous evening had in no way dulled the freshness of my enjoyment, and for a few minutes I was content to lie there pleasantly indifferent to everything except the flavour of the tobacco.

Then my mind began to work. Sonia’s questions had once again started a train of thought which ever since the trial had been running through my brain with maddening persistence. If I had not killed Marks, who had? How often had I asked myself that during the past three years, and how often had I abandoned the problem in utter weariness! Sometimes, indeed, I had been almost tempted to think the jury must have been right — that I must have struck the brute on the back of the head without realizing in my anger what I was doing. Then, when I remembered how I had left him crouching against the wall, spitting out curses at me through his cut and bleeding lips, I knew that the idea was nonsense. The wound which they found in his head must have killed him instantly. No man who had received a blow like that would ever speak or move again.

The one thing I felt certain of was that in some mysterious way or other George was mixed up in the business. It was incredible that he could have acted as he did at the trial unless he had had some stronger reason than mere dislike for me. That he did dislike me I knew well, but my six years’ association with him had taught me that he would never allow any personal motive to interfere with a chance of making money. By sending me to the gallows or into penal servitude he was practically ruining himself, for with all his acuteness and business knowledge he was quite deficient in any sort of inventive power. And yet he had not hesitated to do it, and to do it by a piece of lying sufficiently cold-blooded and deliberate to make Judas pale with envy.

If there had been any apparent chance of his being able to rob me by the proceeding, I could have understood it. But my business interests as far as past inventions went were safe in the hands of my lawyers, and although I had told him a certain amount about the new explosive which I had been working at, it was quite impossible for him to turn it to any practical use.

No, George must have had some other reason for perjuring his unpleasant soul, and the only one I could think of was that he had purposely turned the case against me in order to shield the real murderer. He had been fairly well acquainted with the dead man, I knew — their tastes indeed ran on somewhat similar lines — and it was just possible that he was aware who had committed the crime.

The thought filled me, as it always had filled me, with a bitter fury. Again and again in my cell I had fancied myself escaping from the prison and choking the truth out of my cousin’s throat with my fingers, and now that the first part of this picture had come true, I vowed silently to myself that nothing should stop the remainder from following it. Whatever McMurtrie might propose, I would see George once again face to face, even if death or recapture was the price I had to pay.

I had just arrived at this conclusion when I heard the sound of footsteps in the passage outside. Then the handle of the door turned, and McMurtrie appeared on the threshold with Savaroff looming up behind him. There was a moment’s silence, while the doctor stood there smiling down on me as blandly as ever.

“May we come in?” he inquired. “We are not interrupting your tea, I hope.”

“No, I have done tea, thank you,” I said, with a gesture towards the tray.

Why it was so, I can’t say, but McMurtrie’s politeness always filled me with a feeling of repulsion. There was something curiously sinister about it.

He stepped forward into the room, followed by Savaroff, who closed the door behind him. The latter then lounged across and sat down on the window-sill, McMurtrie remaining standing by my bedside.

“You have read the Mail, I see,” he said, picking up the paper. “I hope you admired the size of the headlines.”

“It’s the type of compliment,” I replied, “that I have had rather too much of.”

Savaroff broke out into a short gruff laugh. “Our friend,” he said, “is modest — so modest. He does not thirst for more fame. He would retire into private life if they would let him.”

He chuckled to himself, as though enjoying the subtlety of his own humour. Unlike his daughter, he spoke English with a distinctly foreign accent.

“Ah, yes,” said Dr. McMurtrie amiably; “but then, Mr. Lyndon is one of those people that we can’t afford to spare. Talents such as his are intended for use.” He took off his glasses and began to polish them thoughtfully. “One might almost say that he held them in trust — in trust for Providence.”

There was a short silence.

“And is it on account of my talents that you have been kind enough to shelter me?” I asked bluntly.

The doctor readjusted his pince-nez, and seated himself with some deliberation on the foot of the bed.

“The instinct to assist a hunted fellow-creature,” he observed, “is almost universal.” Then he paused. “I take it, Mr. Lyndon, that you are not particularly anxious to rejoin your friends in Princetown?”

I shook my head. “Not if there is a more pleasant alternative.”

Savaroff grunted. “No alternative is likely to be more unpleasant for you,” he said harshly.

The touch of bullying in his tone put my back up at once. “Indeed!” I said: “I can imagine several.”

McMurtrie’s smooth voice intervened. “But ours, Mr. Lyndon, is one which I think will make a very special appeal to you. How would you like to keep your freedom and at the same time take up your scientific work again?”

I looked at him closely. For once there was no trace of mockery in his eyes.

“I should like it very much indeed, if it was possible,” I answered.

McMurtrie leaned forward a little. “It is possible,” he said quietly.

There was a short pause. Savaroff pulled out a cigar, bit off the end, and spat it into the fireplace. Then he reached sideways to the chest of drawers for a match.

“Explain to him,” he said, jerking his head towards me.

McMurtrie glanced at him — it seemed to me a shade impatiently. Then he turned back to me.

“For some time before Mr. Marks’s unfortunate death,” he said slowly, “you had been experimenting with a new explosive.”

I nodded my head. I had no idea how he had got his information, for as far as I was aware George was the only person who had any knowledge of my secret.

“And I believe you were just on the point of success when you were arrested?”

“Theoretically I was,” I said. “These matters don’t always work out quite so well when you put them to a practical test.”

“Still, you yourself were quite satisfied with the prospects?”

I nodded again.

“And unless I am wrong, this new explosive will be immensely more powerful than anything now in use?”

“Immensely,” I repeated; “in fact, there would be no practical comparison between them.”

“Can you give me any idea as to its strength?”

I hesitated. “According to my calculations,” I said slowly, “it ought to prove at least twenty times as powerful as gun-cotton.”

Savaroff uttered a hoarse exclamation and sat upright in his seat.

“Are you speaking the truth?” he asked roughly.

I stared him full in the face, and then without answering turned back to McMurtrie.

The latter made a gesture with his hand. “Leave the matter to me, Savaroff,” he said sharply. “I understand Mr. Lyndon better than you do.” Then addressing me: “Supposing you had all the things that you required, how long would it take you to manufacture some of this powder — or whatever it is?”

“It’s difficult to say,” I answered. “Perhaps a week; perhaps a couple of months. I could make the actual stuff at once provided I had the materials, but it’s a question of doing it in such a way that one can handle it safely for practical purposes. I was experimenting on that very point at the time of my arrest.”

McMurtrie nodded his head slowly. “You have been candid with us,” he said, “and now I will be equally candid with you. My friend M. Savaroff and myself are very largely interested in the manufacture of high explosives. The appearance of an invention like yours on the market would be a very serious matter indeed for us. On the other hand, if we had control of it, we should, I imagine, be in a position to dictate our own terms.”

“You certainly would,” I said; “there is no question about that. My explosive would be no more expensive to manufacture than cordite.”

“So you see when some exceedingly convenient chance brought you in through our kitchen window it naturally occurred to me to invite you to stay and discuss the matter. You happen to be in a position in which you could be useful to us, and I think that we, on the other hand, might be of some assistance to you.”

He leant back and watched me with that cold smile of his.

“What do you say, Mr. Lyndon?” he added.

I did some rapid but necessary thinking. It was quite true that the new explosive would knock the bottom out of the present methods of manufacture, and McMurtrie’s interests in the matter might well be large enough to make him run the risk of helping me. There seemed no reason to doubt that he was speaking the truth — and yet, somehow or other I mistrusted him — mistrusted him from my soul.

“How did you know about my experiments?” I asked quietly.

He shrugged his shoulders. “There are such things as trade secrets. It is necessary for a business man to keep in touch with anything that may threaten his interests.”

I hesitated a second. “What is it that you propose — exactly?” I inquired.

I saw — or thought I saw — the faintest possible gleam of satisfaction steal into his eyes.

“I propose that you should finish your experiments as soon as possible, make some of this explosive, and hand the actual stuff and the full secret of its manufacture over to us. In return I will guarantee you your freedom, and let you have a quarter interest in all profits we make out of your invention.”

He brought out these somewhat startling terms as coolly as though it were an every-day custom of his to do business with escaped convicts. I bent down from the bed, and under cover of picking up my second cigarette from the tray, secured a few useful moments for considering the situation.

“I have no objection to the bargain,” I said slowly, helping myself to a match off the table; “the only question is whether it is possible to carry it out. My experiments aren’t the kind that can be conducted in a back bedroom. I should want a large shed of some kind, and the farther away it was from any houses the better. There is always the chance of blowing oneself up at this sort of business, and in that case an explosive like mine would probably wreck everything within a couple of miles.”

“You shall work under any conditions you please,” said McMurtrie amiably. “If it suits you we will fix you up a hut and some sheds down on the Thames marshes, and you can live there till the experiments are finished.”

“But I should be recognized,” I objected. “I am bound to be recognized. I am fairly well known as it is, and with my picture and description placarded all over England, I shouldn’t stand a dog’s chance. However lonely a place it was, some one would be bound to see me and give me away sooner or later.”

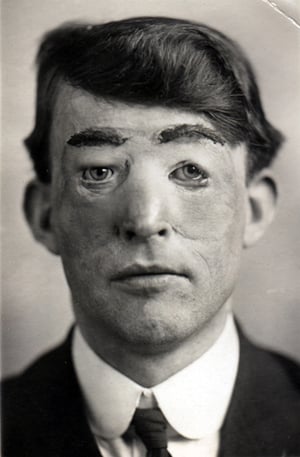

McMurtrie shook his head. “You may be seen,” he said, “but there is no reason why you should be recognized.”

I paused in the act of lighting my cigarette. “What do you mean?” I asked with some curiosity.

“My dear Mr. Lyndon,” said McMurtrie, courteously, “as a scientist yourself you don’t imagine that it’s beyond the art of an intelligent surgeon to cope with a little difficulty like that?”

“But in what way?” I objected. “A disguise? Any one can see through a disguise except in novels.”

The doctor smiled. “I am not suggesting a wig and a pair of spectacles,” he observed. “It is rather too late in the world’s history for that sort of thing.” Then he stopped and studied me for an instant attentively. “In a fortnight, and practically without hurting you,” he added, “I can make you as safe from the police as if you were dead and buried.”

I sat up in bed. “Under the circumstances,” I said, “you’ll excuse my being a little inquisitive.”

“Oh, there is no secret about it. Any surgeon could do it. I have only to alter the shape of your nose a trifle, and make your forehead rather higher and wider. A stain of some sort will do the rest.”

“Yes,” I said; “but what about the first part of the programme?”

He shrugged his shoulders. “Child’s play,” he answered. “Merely a question of paraffin injections and the X-rays.”

He spoke with such careless confidence that for once it was impossible to doubt his sincerity.

I lay back again and drew in a large exulting lungful of cigarette smoke. I had suddenly realized that if McMurtrie’s offer was genuine, and he could really do what he promised, there were no longer any difficulties in the way of my getting at George. The idea of meeting him, and perhaps even speaking to him, without his being able to recognize me filled me with a wicked satisfaction that no words can do justice to.

I don’t think I betrayed my emotion, however, for McMurtrie’s keen eyes were on me, and I was not in the least anxious to take him into my confidence. I blew out the smoke in a grey cloud, and then, raising myself on my elbow carefully flicked the ash off my cigarette.

“How am I to know that you will keep your promise?” I asked.

Savaroff made an angry movement, but before he could speak, McMurtrie had broken in.

“You forget what an embarrassing position we shall be putting ourselves in, Mr. Lyndon,” he said with perfect good temper. “Shielding a runaway convict is an indictable offence — to say nothing of altering his appearance. As for the money” — he made a little gesture of contempt — “well, do you think it would pay us to cheat you? There is always the chance that a gentleman who can invent things like this explosive and the Lyndon-Marwood torpedo may have other equally satisfactory notions.”

“Very well,” I said quietly. “I will accept the offer on one condition — that I can have a week in London before beginning work.”

With an oath Savaroff started up from the window-sill.

“Gott in Himmel! and who are you to make terms?” he exclaimed roughly. “Why, we have only to send you back to the prison and you will be flogged like a dog!”

“In which distressing event,” I observed, “you would not get your explosive.”

“My dear Savaroff,” interrupted McMurtrie, soothingly, “there is no need to threaten Mr. Lyndon. I am sure that he appreciates the situation.” Then he turned to me. “I suppose you have some reason for making this condition?”

Silently in my heart I invoked the shade of Ananias.

“If you had been in Dartmoor three years,” I said, with a rather well-forced laugh, “you would find several excellent reasons for wanting a week in London.”

My acting must have been good, for I could have sworn I saw a faint expression of relieved contempt flicker across McMurtrie’s face.

“I see. A little holiday — a brief taste of the pleasures of liberty! Well, that seems to me a very natural and reasonable request. What do you think, Savaroff?”

That gentleman contented himself with a singularly ungracious grunt.

“I don’t think there would be much risk about it,” I said boldly. “If you can change my appearance as completely as you say you can, no one would be the least likely to recognize me. After three years of that dog’s life up there I can’t settle down in a hut on the Thames marshes without having a few days’ fun first. I should be very careful what I did naturally. I have had quite enough of the prison to appreciate being outside.”

McMurtrie nodded. “Very well,” he said slowly. “I see no objection to your having your ‘few days’ fun’ in London if you want them. It would be safer perhaps to get you away from this house as soon as possible. I should think three weeks would be quite enough for our purposes here — and I daresay it will take us a month to fix up a satisfactory place for you to work in.” Then he paused. “Of course if you go to town,” he added, “you will have to stay at some address we shall arrange for, and you will have to be ready to start work directly we tell you to.”

“Naturally,” I said; “I only want —”

I was saved from finishing my falsehood by a sudden sound from outside — the sound of a swing gate banging against its post. For a moment I had a horrible feeling that it might be the police.

Savaroff jumped up and looked out of the window. Then with a little guttural exclamation he turned back to McMurtrie.

“Hoffman!” he muttered, apparently in some surprise.

Who Mr. Hoffman might be I had not the faintest notion, but the mention of the name brought the doctor to his feet at once. I think he was rather annoyed with Savaroff for being unnecessarily communicative. When he spoke, however, it was with his usual perfect composure.

“Well, we will leave you at peace now, Mr. Lyndon. I should try to go to sleep again for a little while if I were you. I will come up later and see whether you would like some supper.” He stopped and looked round the room. “Is there anything else you want that you haven’t got?”

“If you could advance me a box of cigarettes,” I said, “it shall be the first charge on the new explosive.”

He nodded, smiling. “I will send Sonia up with it,” he answered. Then, following Savaroff, he went out into the passage, carefully closing the door after him.

Left alone, I lay back on the pillow in a frame of mind which I believe novelists describe as “chaotic.” I had expected something rather unusual from my interview with McMurtrie, but these proposals of his could hardly be classed under such a mild heading as that. For sheer unexpectedness they about took the biscuit.

I had read in books of a man’s appearance being altered so completely that even his best friends failed to recognize him, but it had never occurred to me that such a thing could be done in real life — let alone in the simple fashion outlined by the doctor. Of course, if he was speaking the truth, there seemed no reason why his plan, fantastic as it might sound, should not turn out perfectly successful. A private hut on the Thames marshes was about the last place in which you would look for an escaped Dartmoor convict, especially when he had vanished into thin air within a few miles of Devonport.

What worried me most in the matter was my apparent good luck in having fallen on my feet in this amazing fashion. There is a limit to one’s belief in coincidences, and the extraordinary combination of chances suggested by McMurtrie’s smooth explanations was just a little too stiff for me to swallow. I felt sure that he was lying in some important particulars — but precisely which they were I was unable to guess for certain.

That he wanted the secret of the new explosive, and wanted it badly, there could be no doubt, but neither he nor Savaroff in the least suggested to me a successful manufacturer of cordite or anything else. They seemed to me to belong to a much more interesting if less conventional type, and I couldn’t help wondering what on earth such a curious trio as they and Sonia could be doing tucked away in an ill-furnished, deserted-looking country house in a corner of South Devon.

However it was no good worrying, for as far as I was concerned it was painfully clear that there was no alternative. If I declined their offer and refused to let McMurtrie carve my face about, they had only to turn me out, and in a few hours I should probably be back in my cell with the cheerful prospect of chains, a flogging, and six months’ semi-starvation in front of me.

Anything was better than that — even the wildest of plunges in the dark. Indeed I am not at all sure that the mystery that surrounded McMurtrie’s offer did not lend it a certain charm in my eyes. My life had been so infernally dull for the last three years that the prospect of a little excitement, even of an unpleasant kind, was by no means wholly disagreeable.

At least I had my week’s “fun” in London to look forward to, and the thought of that alone would have been quite enough to make me go through with anything. I had lied to McMurtrie about my object, but the falsehood, such as it was, did not sit very heavily on my conscience. The precise meaning of “fun” is purely a matter of opinion, and I was as much entitled to my definition as he was to his. After all, if a convicted murderer can’t be a little careless about the exact truth, who the devil can?

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.