A Rogue By Compulsion (4)

By:

April 21, 2016

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

Whatever my intentions may have been — and they were pretty venomous when I jumped up — the revolver was really an unnecessary precaution. Directly I was on my feet I went as giddy as a kite, and it was only by clutching the chair that I saved myself from toppling over. I was evidently in a worse way than I imagined.

Lowering his weapon the doctor repeated his order.

“Sit down, man, sit down. No one means you any harm here.”

“Who is it in the car?” I demanded, fighting hard against the accursed feeling of faintness that was again stealing through me.

“They are friends of mine. They have nothing to do with the police. You will see in a minute.”

I sat down, more from necessity than by choice, and as I did so I heard the car draw up outside the back door.

Crossing to the window the doctor threw up the sash.

“Savaroff!” he called out.

There came an answer in a man’s voice which I was unable to catch.

“Come in here,” went on McMurtrie. “Don’t bother about the car.” He turned back to me. “Drink this,” he added, pouring out some more brandy into the wine-glass. I gulped it down and lay back again in my chair, tingling all through.

He took my wrist and felt my pulse for a moment. “I know you are feeling bad,” he said, “but we’ll get your wet clothes off and put you to bed in a minute. You will be a different man in the morning.”

“That will be very convenient,” I observed faintly.

There was a noise of footsteps outside, the handle of the door turned, and a man — a huge bear of a man in a long Astrachan coat — strode heavily into the room. He was followed by a girl whose face was almost hidden behind a partly-turned-back motor veil. When they caught sight of me they both stopped abruptly.

“Who’s this?” demanded the man.

Dr. McMurtrie made a graceful gesture towards me with his hand.

“Allow me,” he said, “to introduce you. Monsieur and Mademoiselle Savaroff — our distinguished and much-sought-after friend Mr. Neil Lyndon.”

The big man gave a violent start, and with a little exclamation the girl stepped forward, turning back her veil. I saw then that she was remarkably handsome, in a dark, rather sullen-looking sort of way.

“You will excuse my getting up,” I said weakly. “It doesn’t seem to agree with me.”

“Mr. Lyndon,” explained the doctor, “is fatigued. I was just proposing that he should go to bed when I heard the car.”

“How in the name of Satan did he get here?” demanded the other man, still staring at me in obvious amazement.

“He came in through the window with the intention of borrowing a little food. I had happened to see him in the garden, and being under the natural impression that he was—er—well, another friend of ours, I ventured to detain him.”

Savaroff gave a short laugh. “But it’s incredible,” he muttered.

The girl was watching me curiously. “Poor man,” she exclaimed, “he must be starving!”

“My dear Sonia,” said McMurtrie, “you reflect upon my hospitality. Mr. Lyndon has been faring sumptuously on bread and milk.”

“But he looks so wet and ill.”

“He is wet and ill,” rejoined the doctor agreeably. “That is just the reason why I am going to ask you to heat some water and light a fire in the spare bedroom. We don’t want to disturb Mrs. Weston at this time of night. I suppose the bed is made up?”

Sonia nodded. “I think so. I’ll go up and see anyhow.”

With a last glance at me she left the room, and Savaroff, taking off his coat, threw it across the back of a chair. Then he came up to where I was sitting.

“You don’t look much like your pictures, my friend,” he said, unwinding the scarf that he was wearing round his neck.

“Under the circumstances,” I replied, “that’s just as well.”

He laughed again, showing a set of strong white teeth. “Yes, yes. But the clothes and the short hair — eh? They would take a lot of explaining away. It was fortunate for you you chose this house — very fortunate. You find yourself amongst friends here.”

I nodded.

I didn’t like the man — there was too great a suggestion of the bully about him, but for all that I preferred him to McMurtrie.

It was the latter who interrupted. “Come, Savaroff, you take Mr. Lyndon’s other arm and we’ll help him upstairs. It is quite time he got out of those wet things.”

With their joint assistance I hoisted myself out of the chair and, leaning heavily on the pair of them, hobbled across to the door. Every step I took sent a thrill of pain through me, for I was as stiff and sore as though I had been beaten all over with a walking-stick. The stairs were a bit of a job too, but they managed to get me up somehow or other, and I found myself in a large sparsely furnished hall lit by one ill-burning gas jet. There was a door half open on the left, and through the vacant space I could see the flicker of a freshly lighted fire.

They helped me inside, where we found the girl Sonia standing beside a long yellow bath-tub which she had set out on a blanket.

“I thought Mr. Lyndon might like a hot bath,” she said. “It won’t take very long to warm up the water.”

“Like it!” I echoed gratefully; and then, finding no other words to express my emotions, I sank down in an easy chair which had been pushed in front of the fire.

I think the brandy that McMurtrie had given me must have gone to my head, or perhaps it was merely the sudden sense of warmth and comfort coming on top of my utter fatigue. Anyhow I know I fell gradually into a sort of blissful trance, in which things happened to me very much as they do in a dream.

I have a dim recollection of being helped to pull off my soaked and filthy clothes, and later on of lying back with indescribable felicity in a heavenly tub of hot water.

Then I was in bed and somebody was rubbing me, rubbing me all over with some warm pungent stuff that seemed to take away the pain in my limbs and leave me just a tingling mass of drowsy contentment.

After that — well, after that I suppose I fell asleep.

I base this last idea upon the fact that the next thing I remember is hearing some one say in a rather subdued voice: “Don’t wake him up. Let him sleep as long as he likes — it’s the best thing for him.”

Whereupon, as was only natural, I promptly opened my eyes.

Dr. McMurtrie and the dark girl were standing by my bedside, looking down at me.

I blinked at them for a moment, wondering in my half-awake state where the devil I had got to. Then suddenly it all came back to me.

“Well,” said the doctor smoothly, “and how is the patient today?”

I stretched myself with some care. I was still pretty stiff, and my throat felt as if some one had been scraping it with sand-paper, but all the same I knew that I was better—much better.

“I don’t think there’s any serious damage,” I said hoarsely. “How long have I been asleep?”

He looked at his watch. “As far as I remember, you went to sleep in your bath soon after midnight. It’s now four o’clock in the afternoon.”

I started up in bed. “Four o’clock!” I exclaimed. “Good Lord! I must get up — I —”

He laid his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t be foolish, my friend,” he said. “You will get up when you are fit to get up. At the present moment you are going to have something to eat.” He turned to the girl. “What are you thinking of giving him?” he asked.

“There are plenty of eggs,” she said, “and there’s some of that fish we had for breakfast.” She answered curtly, almost rudely, looking at me while she spoke. Her manner gave me the impression that for some reason or other she and McMurtrie were not exactly on the best of terms.

If that was so, he himself betrayed no sign of it. “Either will do excellently,” he said in his usual suave way, “or perhaps our young friend could manage both. I believe the Dartmoor air is most stimulating.”

“I shall be vastly grateful for anything,” I said, addressing the girl. “Whatever is the least trouble to cook.”

She nodded and left the room without further remark — McMurtrie looking after her with what seemed like a faint gleam of malicious amusement.

“I have brought you yesterday’s Daily Mail,” he said; “I thought it would amuse you to read the description of your escape. It is quite entertaining; and besides that there is a masterly little summary of your distinguished career prior to its unfortunate interruption.” He laid the paper on the bed. “First of all, though,” he added, “I will just look you over. I couldn’t find much the matter with you last night, but we may as well make certain.”

He made a short examination of my throat, and then, after feeling my pulse, tapped me vigorously all over the chest.

“Well,” he said finally, “you have been through enough to kill two ordinary men, but except for giving you a slight cold in the head it seems to have done you good.”

I sat up in bed. “Dr. McMurtrie,” I said bluntly, “what does all this mean? Who are you, and why are you hiding me from the police?”

He looked down on me, with that curious baffling smile of his. “A natural and healthy curiosity, Mr. Lyndon,” he said drily. “I hope to satisfy it after you have had something to eat. Till then —” he shrugged his shoulders — “well, I think you will find the Daily Mail excellent company.”

He left the room, closing the door behind him, and for a moment I lay there with an uncomfortable sense of being tangled up in some exceedingly mysterious adventure. Even such unusual people as Dr. McMurtrie and his friends do not as a rule take in and shelter escaped convicts purely out of kindness of heart. There must be a strong motive for them to run such a risk in my case, but what that motive could possibly be was a matter which left me utterly puzzled. So far as I could remember I had never seen any of the three before in my life.

I glanced round the room. It was a big airy apartment, with ugly old-fashioned furniture, and two windows, both of which looked out in the same direction. The pictures on the wall included an oleograph portrait of the late King Edward in the costume of an Admiral, a large engraving of Mr. Landseer’s inevitable stag, and several coloured and illuminated texts. One of the latter struck me as being topical if a little inaccurate. It ran as follows:

THE WICKED FLEE WHEN NO MAN PURSUETH

Over the mantelpiece was a mirror in a mahogany frame. I gazed at it idly for a second, and then a sudden impulse seized me to get up and see what I looked like. I turned back the clothes and crawled out of bed. I felt shaky when I stood up, but my legs seemed to bear me all right, and very carefully I made my way across to the fireplace.

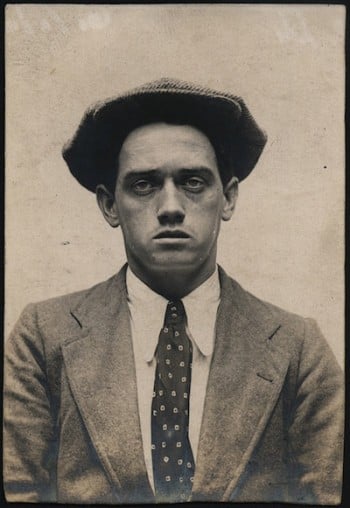

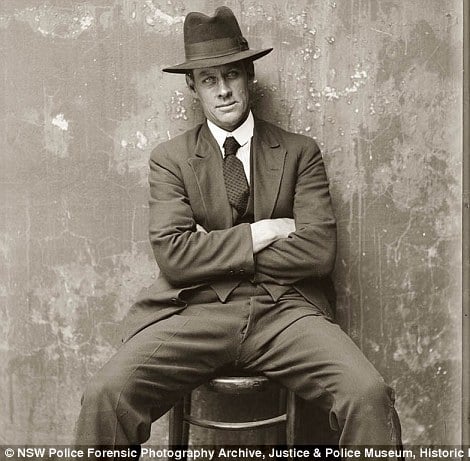

The first glance I took in the mirror gave me a shock that nearly knocked me over. A cropped head and three days’ growth of beard will make an extraordinary difference in any one, but I would never have believed they could have transformed me into quite such an unholy-looking ruffian as the one I saw staring back at me out of the glass. If I had ever been conceited about my personal appearance, that moment would have cured me for good.

Satisfied with a fairly brief inspection I returned to the bed, and arranging the pillow so as to fit the small of my back, picked up the Daily Mail. I happened to open it at the centre page, and the big heavily leaded headlines caught my eyes straight away.

ESCAPE OF NEIL LYNDON FAMOUS PRISONER BREAKS OUT OF DARTMOOR SENSATIONAL CASE RECALLED

With a pleasant feeling of anticipation I settled down to read.

From our own Correspondent. Princetown.

Neil Lyndon, perhaps the most famous convict at present serving his sentence, succeeded yesterday in escaping from Princetown. At the moment of writing he is still at large.

He formed one of a band of prisoners who were returning from the quarries late in the afternoon. As the men reached the road which leads through the plantation to the main gate of the prison, one of the warders in charge was overcome by an attack of faintness. In the ensuing confusion, a convict of the name of Cairns, who was walking at the head of the gang, made a sudden bolt for freedom. He was immediately challenged and fired at by the Civil Guard.

The shot took partial effect, but failed for the moment to stop the runaway, who succeeded in scrambling off into the wood. He was pursued by the Civil Guard, and it was at that moment that Lyndon, who was in the rear of the gang, also made a dash for liberty.

He seems to have jumped the low wall which bounds the plantation, and although fired at in turn by another of the warders, apparently escaped injury.

Running up the hill through the trees, he reached the open slope of moor on the farther side which divides the plantation from the main wood. While he was crossing this he was seen from the roadway by that well-known horse-dealer and pigeon-shot, Mr. Alfred Smith of Shepherd’s Bush, who happened to be on a walking tour in the district.

Mr. Smith, with characteristic sportsmanship, made a plucky attempt to stop him; but Lyndon, who had picked up a heavy stick in the plantation, dealt him a terrific blow on the head that temporarily stunned him. He then jumped the railings and took refuge in the wood.

The pursuing warders came up a few minutes later, but by this time a heavy mist was beginning to settle down over the moor, rendering the prospect of a successful search more than doubtful. The warders therefore surrounded the wood with the idea of preventing Lyndon’s escape.

Taking advantage of the fog, however, the latter succeeded in slipping out on the opposite side. He was heard climbing the railings by Assistant-warder Conway, who immediately gave the alarm and closed with the fugitive. The other warders came running up, but just before they could reach the scene of the struggle Lyndon managed to free himself by means of a brutal kick, and darting into the fog disappeared from sight.

It is thought that he has made his way over North Hessary and is lying up in the Walkham Woods. In any case it is practically certain that he will not be at liberty much longer. It is impossible for him to get food except by stealing it from a cottage or farm, and directly he shows himself he is bound to be recaptured.

Considerable excitement prevails in the district, where all the inhabitants are keenly on the alert.

THE MARKS MURDER ECHOES OF A FAMOUS CASE

The escape of Neil Lyndon recalls one of the most famous crimes of modern days.

On the third of October four years ago, as most of our readers will remember, a gentleman named Mr. Seton Marks was found brutally murdered in his luxurious flat on the Chelsea Embankment. It was thought at first that the crime was the work of burglars, for Mr. Marks’s rooms contained many art treasures of considerable value. A further examination, however, revealed the fact that nothing had been tampered with, and the next day the whole country was startled and amazed to learn that Neil Lyndon had been arrested on suspicion.

At the trial it was proved beyond question that the accused was the last person in the company of the murdered man. He had gone round to Mr. Marks’s flat at four o’clock in the afternoon, and had apparently been admitted by the owner. Two hours later Mr. Marks’s servant returning to the flat was horrified to find his master’s dead body lying in the sitting-room. Death had been inflicted by means of a heavy blow on the back of the head, but the state of the dead man’s face showed that he had been brutally mishandled before being killed.

The accused, while maintaining his innocence of the murder, did not deny either his visit to the flat, or the fact that he had inflicted the other injuries on the deceased. He declined to state the cause of their quarrel, but the defending counsel produced a witness in the person of Miss Joyce Aylmer, a young girl of sixteen, who was able to throw some light on the matter.

Miss Aylmer, a young lady of considerable beauty, stated that for about a year she had been working as an art student in Chelsea, and used occasionally to sit to artists for the head. On the afternoon before the murder she had had a professional engagement of this kind with Mr. Marks. There had been a visitor in the flat when she arrived, but he had left as soon as she came in. Subsequently, according to her statement, the deceased had acted towards her in an outrageous and disgraceful manner. She had escaped from his flat with difficulty, and had subsequently informed Mr. Lyndon of what had taken place.

In his re-examination, the accused admitted that it was on account of Miss Aylmer’s statement he had visited the flat. Up till then, he declared, he had had no quarrel with the deceased.

This statement, however, was directly contradicted by Lyndon’s partner, Mr. George Marwood. Giving his evidence with extreme reluctance, Mr. Marwood stated that for some time bad blood had undoubtedly existed between Mr. Marks and the accused. He added that in his own hearing on two separate occasions the latter had threatened to kill the deceased.

Pressed still further, he admitted meeting Mr. Lyndon in Chelsea on the night of the murder, when the latter had to all intents and purposes acknowledged his guilt.

On the evidence there could naturally be only one verdict, and Lyndon was found guilty and sentenced to death by Mr. Justice Owen.

A tremendous agitation in favour of his reprieve broke out at once. Apart from the peculiar circumstances under which the crime was committed, it was urged that Mr. Lyndon’s services to the country as an inventor should be taken into consideration. Within twenty-four hours over a million people had signed a petition in his favour, and the following day His Majesty was pleased to commute the sentence to one of penal servitude for life.

There is little doubt, however, that Lyndon would have been released at the end of ten or twelve years.

THE ESCAPED CONVICT’S CAREER

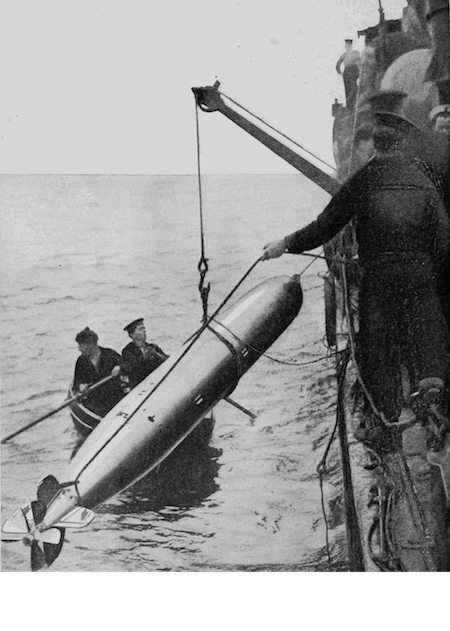

Neil Lyndon is the only son of the well-known explorer Colonel Grant Lyndon, who perished on the Upper Amazon some fifteen years ago. He was educated at Haileybury, and Oriel College, Oxford, where he took the highest honours in chemistry and mathematics. Coming down, he entered into partnership with his cousin Mr. George Marwood, and between them the two young inventors met with early and remarkable success. Their greatest achievement was of course the construction of the Lyndon-Marwood automatic torpedo, which was taken up four years ago, after exhaustive tests, by the British Government.

Lyndon is a man of exceptionally powerful physique. He successfully represented Oxford as a heavy-weight boxer in his last term, and the following year was runner up in the Amateur Championship. He is also a fine long-distance swimmer, and a well-known single-handed yachtsman.

Mr. George Marwood, whose painful position in connection with the trial aroused considerable sympathy, has carried on the business alone since his partner’s conviction. Quite recently, as our readers will recall, he was the victim of a remarkable outrage at his offices in Victoria Street. While he was working there by himself late at night, a couple of masked men broke into the building, bound and gagged him, and proceeded to ransack the safe. It is said that they secured plans and documents of considerable value, but owing to the non-arrest of the thieves the exact details have never come to light.

So ended the Daily Mail.

I finished reading, and taking a long breath, laid down the paper. Up till then I had heard nothing about the news contained in the last paragraph, and it sent my memory back at once to the big well-lighted room in Victoria Street where George and I had spent so many hours together. I wondered what the valuable “plans and documents” might be which the thieves were supposed to have secured. In my day we had always been pretty careful about what we left at the office, and any really important plans — such as those of the Lyndon-Marwood torpedo — were invariably kept at the safe deposit across the street.

From George and the office my thoughts drifted away over the whole of that crowded time referred to in the paper. Brief and bald as the narrative was, it brought up before me a dozen vivid memories, which jostled each other simultaneously in my mind. I saw again poor little Joyce’s tear-stained face, and remembered the shuddering relief with which she had clung to me as she sobbed out her story. I could recall the cold rage in which I had set out for Marks’s flat, and that first savage blow of mine that sent him reeling and crashing into one of his own cabinets.

Then I was in court again, and George was giving his evidence — the lying evidence that had been meant to send me to the gallows. I remembered the cleverly assumed reluctance with which he had apparently allowed his statements to be dragged from him, and my blood rose hot in my throat as I thought of his treachery.

Above all I seemed to see the fat red face of Mr. Justice Owen, with the ridiculous little three-cornered black cap above it. He had been very cut up about sentencing me to death, had poor old Owen, and I could almost hear the broken tones in which he had faltered out the words:

“… taken from the place where you now stand to the place whence you came — hanged by the neck until your body be dead — and may God have mercy on your soul.”

At this cheerful point in my reminiscences I was suddenly interrupted by a sharp knock at the door.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.