A Rogue By Compulsion (3)

By:

April 15, 2016

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

I was going so fast that everything seemed to happen simultaneously. I had one blurred vision of him spinning round and yelling to me to stop: then the next moment I had flashed past him and was racing across the bridge.

Whether he recognized me for certain I can’t say. I think not, or he would probably have fired sooner than he did: as it was, my rush had carried me three quarters of the way up the opposite hill before he could make up his mind to risk a shot.

Bang went his carbine, and at the same instant, with a second loud report, the tire of my back wheel abruptly collapsed. It was a good shot if he had aimed for it, and what’s more it came unpleasantly near doing the trick. The old bike swerved violently, but with a wild wrench I just succeeded in righting her. For a second I heard him shouting and running behind me, and then, working like a maniac, I bumped up the rest of the slope, and disappeared over the protecting dip at the top.

Of my progress for the next mile or so I have only the most confused recollection. It was like one of those ghastly things that occasionally happen to one in a nightmare. I just remember pedalling blindly along, with the back wheel grinding and jolting beneath me and the moonlit road rising and falling ahead. It must have been more instinct than anything else that kept me going, for I was in the last stages of hunger and weariness, and most of the time I scarcely knew what I was doing.

At last, after wobbling feebly up a long slope, I found I had reached the extreme edge of the Moor. Right below me the road dropped down for several hundred feet into a broad level expanse of fields and woods. Six or seven miles away the lights of Plymouth and Devonport threw up a yellow glare into the sky, and beyond that again I could just see the glint of the moonlight shining on the sea.

It was no good stopping, for I knew that in an hour or so the mounted warders would be again on my track. So clapping on both brakes, I started off down the long descent, being careful not to let the machine get away with me as it had done on the previous hill.

At the bottom, which I somehow reached in safety, I found a sign-post with two hands, one marked Plymouth and the other Devonport. I took the latter road, why I can hardly say, and summoning up my almost spent energies I pedalled off shakily between its high hedges.

How I got as far as I did remains a mystery to me to this day. I fell off twice from sheer weakness, but on each occasion I managed to drag myself back into the saddle again, and it was not until my third tumble, that I decided I could go no farther.

I was in a dark stretch of road bounded on each side by thick plantations. It was a good place to lie up in, but unfortunately there was another and more pressing problem in front of me. Half delirious as I was, I realized that unless I could find something to eat that night my career as an escaped convict was pretty near its end.

I picked myself up, and with a great effort managed to drag the bicycle to the side of the road. Then, clutching the rail that bounded the plantation, I began to stagger slowly forward along the slightly raised path. I think I had a sort of vague notion that there might be something to eat round the next corner.

I had progressed in this fashion for perhaps forty yards, when quite unexpectedly both the trees and the railings came to an end. I remained swaying and half incredulous for a moment: then I began to realize that I was standing in front of an open gate looking up an exceedingly ill-kept drive. At the end of this drive was a house, and the moonlight shining full on the front of it showed me that the whole place had about as forlorn and neglected an appearance as an inhabited building could very well possess. That it was inhabited there could be no doubt, for in the small glass square above the hall door I could see a feeble glimmer of light.

No one could have called it an inviting-looking place, but then I wasn’t exactly waiting for invitations where a chance of food was concerned. I just slipped in at the gate, and keeping well in the shadow of the bushes that bounded the drive, I crept slowly and unsteadily forward until I reached a point opposite the front door. I crouched there for a moment, peering up at the house. Except for that flickering gas jet there was no sign of life anywhere; all the windows were shuttered or else in complete darkness.

At first I had a wild idea of ringing the bell and pretending to be a starving tramp. Then I remembered that my description had no doubt been circulated all round the neighbourhood, and that if there was any one in the place they would probably recognize me at once as the missing convict. This choked me off, for though as a rule I have no objection to a slight scuffle, I felt that in my present condition the average housemaid could knock me over with the flick of a duster.

The only alternative scheme that suggested itself to my numbed mind was to commit another burglary. There was a path running down the side of the house, which apparently led round to the back, and it struck me that if I followed this I might possibly come across an unfastened window. Anyhow, it was no good waiting about till I collapsed from exhaustion, so, getting on my feet, I slunk along the laurels as far as the end of the drive, and then crept across in the shadow of an overhanging tree.

I made my way slowly down the path, keeping one hand against the wall, and came out into a small square yard, paved with cobbles, where I found myself looking up at the back of the house. There was a door in the middle with two windows on either side of it, and above these several other rooms—all apparently in complete darkness.

I was beginning to feel horribly like fainting, but by sheer will-power I managed to pull myself together. Going up to the nearest window I peered through the pane. I could see the dim outline of a table with some plates on it just inside, and putting my hand against the bottom sash I gave it a gentle push. It yielded instantly, sliding up several inches with a wheezy rattle that brought my heart into my mouth.

For a moment or two I waited, listening intently for any sound of movement within the house. Then, as nothing happened, I carefully raised the sash a little higher, and poked my head in through the empty window-frame.

It was the kitchen all right: there could be no doubt about that. A strong smell of stale cooking pervaded the warm darkness, and that musty odour brought tears of joy into my eyes. I took one long luxurious sniff, and then with a last effort I hoisted myself up and scrambled in over the low sill.

As my feet touched the floor there was a sharp click. A blinding flash of light shot out from the darkness, striking me full in the face, and at the same instant a voice remarked quietly but firmly: “Put up your hands.”

I put them up.

There was a short pause: then from the other end of the room a man in a dressing-gown advanced slowly to the table in the centre. He was holding a small electric torch in one hand and a revolver in the other. He laid down the former with the light still pointing straight at my face.

“If you attempt to move,” he remarked pleasantly, “I shall blow your brains out.”

With this he walked to the side of the room, struck a match against the wall, and reaching up turned on the gas.

I was much too dazed to do anything, even if I had had the chance. I just stood there with my hands up, rocking slightly from side to side, and wondering how long it would be before I tumbled over.

My captor remained for a moment under the light, peering at me in silence. He seemed to be a man of about sixty — a thin, frail man with white hair and a sharp, deeply lined face. He wore gold-rimmed pince-nez, behind which a pair of hard grey eyes gleamed at me in malicious amusement.

At last he took a step forward, still holding the revolver in his hand.

“A stranger!” he observed. “Dear me — what a disappointment! I hope Mr. Latimer is not ill?”

I had no idea what he was talking about, but his voice sounded very far away.

“If you keep me standing like this much longer,” I managed to jerk out, “I shall most certainly faint.”

I saw him raise his eyebrows in a sort of half-mocking smile.

“Indeed,” he said, “I thought —”

What he thought I never heard, for the whole room suddenly went dim, and with a quick lurch the floor seemed to get up and spin round beneath my feet. I suppose I must have pitched forward, for the last thing I remember is clutching wildly but vainly at the corner of the kitchen table.

My first sensation on coming round was a burning feeling in my lips and throat. Then I suddenly realized that my mouth was full of brandy, and with a surprised gulp I swallowed it down and opened my eyes.

I was lying back in a low chair with a cushion under my head. Standing in front of me was the gentleman in the dressing-gown, only instead of a revolver he now held an empty wine-glass in his hand. When he saw that I was recovering he stepped back and placed it on the table. There was a short pause.

“Well, Mr. Lyndon,” he said slowly, “and how are you feeling now?”

A hasty glance down showed me that the jacket of my overalls had been unbuttoned at the neck, exposing the soaked and mud-stained prison clothes beneath. I saw that the game was up, but for the moment I was too exhausted to care.

My captor leaned against the end of the table watching me closely.

“Are you feeling any better?” he repeated.

I made a feeble attempt to raise myself in the chair. “I don’t know,” I said weakly; “I’m feeling devilish hungry.”

He stepped forward at once, his lined face breaking into something like a smile.

“Don’t sit up. Lie quite still where you are, and I will get you something to eat. Have you had any food today?”

I shook my head. “Only rain-water,” I said.

“You had better start with some bread and milk, then. You have been starving too long to eat a big meal straight away.”

Crossing the room, he pushed open a door which apparently led into the larder, and then paused for a moment on the threshold.

“You needn’t try to escape,” he added, turning back to me. “I am not going to send for the police.”

“I don’t care what you do,” I whispered, “as long as you hurry up with some grub.”

Lying there in the sort of semi-stupor that comes from utter exhaustion, I listened to him moving about in the larder apparently getting things ready. For the moment all thoughts of danger or recapture had ceased to disturb me. Even the unexpected fashion in which I was being treated did not strike me as particularly interesting or surprising: my whole being was steeped in a sense of approaching food.

I saw him re-enter the room, carrying a saucepan, which he placed on a small stove alongside the fireplace. There was the scratching of a match followed by the pop of a gas-ring, and half-closing my eyes I lay back in serene and silent contentment.

I was aroused by the chink of a spoon, and the splash of something liquid being poured out. Then I saw my host coming towards me, carrying a large steaming china bowl in his hand.

“Here you are,” he said. “Do you think you can manage to feed yourself?”

I didn’t trouble to answer. I just seized the cup and spoon, and the next moment I was wolfing down a huge mouthful of warm bread and milk that seemed to me the most perfect thing I had ever tasted. It was followed rapidly by another and another, all equally beautiful.

My host stood by watching me with a sort of half-amused interest.

“I shouldn’t eat it quite so fast,” he observed. “It will do you more good if you take it slowly.”

The first few spoonfuls had already partly deadened my worst pangs, so following his advice I slackened down the pace to a somewhat more normal level. Even then I emptied the bowl in what I think must have been a record time, and with a deep sigh I handed it to him to replenish.

I was feeling better — distinctly better. The food, the rest in the chair, and the comparative warmth of the room were all doing me good in their various ways, and for the first time I was beginning to realize clearly where I was and what had happened.

I suppose my host noticed the change, for he looked at me in an approving fashion as he gave me my second helping.

“There you are,” he said in that curious dry voice of his. “Eat that up, and then we’ll have a little conversation. Meanwhile —” he paused and looked round — “well, if you have no objection I think I will shut that window. I daresay you have had enough fresh air for today.”

I nodded — my mouth was too full for any more elaborate reply — and crossing the room he closed the sash and pulled down the blind.

“That’s better,” he observed, gently rubbing his hands together; “now we are more comfortable and more private. By the way, I don’t think I have introduced myself yet. My name is McMurtrie — Doctor McMurtrie.”

“I am charmed to meet you,” I said, swallowing down a large chunk of bread.

He nodded his head, smiling. “The pleasure is a mutual one, Mr. Lyndon — quite a mutual one.”

The words were simple and smooth enough in themselves, but somehow or other the tone in which they were uttered was not altogether to my taste. It seemed to carry with it the faint suggestion of a cat purring over a mouse. Still I was hardly in a position to be too fastidious, so I accepted his compliment, and went on calmly with my bread and milk.

With the same rather catlike smile Dr. McMurtrie drew up a chair and sat down opposite to me. He kept his right hand in his pocket, presumably on the revolver.

“And now,” he said, “perhaps you have sufficiently recovered to be able to tell me a little about yourself. At present my knowledge of your adventures is confined to the account of your escape in this morning’s Daily Mail.”

I slowly finished the last spoonful of my second helping, and placed the cup beside me on the floor. It was a clumsy device to gain time, for now that the full consciousness of my surroundings had returned to me, I was beginning to think that Dr. McMurtrie’s methods of receiving an escaped convict were, to say the least, a trifle unusual. Was his apparent friendliness merely a blind, or did it hide some still deeper purpose, of which at present I knew nothing?

He must have guessed my thoughts, for leaning back in his chair he remarked half-mockingly: “Come, Mr. Lyndon, it doesn’t pay to be too suspicious. If it will relieve your mind, I can assure you I have no immediate intention of turning policeman, even for the magnificent sum of — how much is it — five pounds, I believe? On mere business grounds I think it would be underrating your market value.”

The slight but distinct change in his voice in the last remark invested it with a special significance. I felt a sudden conviction that for some reason of his own Dr. McMurtrie did not intend to give me up — at all events for the present.

“I will tell you anything you want to know with pleasure,” I said. “Where did the Daily Mail leave off?”

He laughed curtly, and thrusting the other hand into his pocket pulled out a silver cigarette-case.

“If I remember rightly,” he said, “you had just taken advantage of the fog to commit a brutal and quite unprovoked assault upon a warder.” He held out the case.

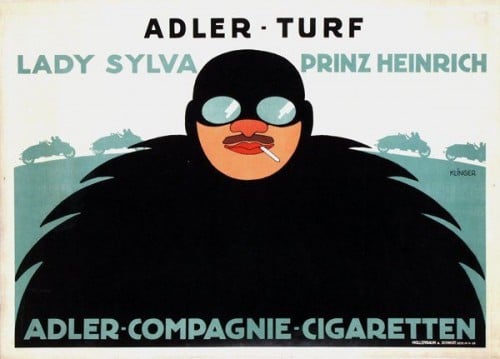

“But try one of these before you start,” he added. “They are a special brand from St. Petersburg, and I think you will enjoy them. There is nothing like a little abstinence to make one appreciate a good tobacco.”

With a shaking hand I pressed the spring. It was three years since I had smoked my last cigarette — a cigarette handed me by the inspector in that stuffy little room below the dock, where I was waiting to be sentenced to death.

If I live to be a hundred I shall never forget my sensations as I struck the match which my host handed me and took in that first fragrant mouthful. It was so delicious that for a moment I remained motionless from sheer pleasure; then lying back again in my chair with a little gasp I drew another great cloud of smoke deep down into my lungs.

The doctor waited, watching me with a kind of cynical amusement.

“Don’t hurry yourself, Mr. Lyndon,” he observed, “pray don’t hurry yourself. It is a pleasure to witness such appreciation.”

I took him at his word, and for perhaps a couple of minutes we sat there in silence while the blue wreaths of smoke slowly mounted and circled round us. Then at last, with a delightful feeling of half-drugged contentment, I sat up and began my story.

I told it him quite simply — making no attempt to conceal or exaggerate anything. I described how the idea of making a bolt had come suddenly into my mind, and how I had acted on it without reflection or hesitation. Step by step I went quietly through my adventures, from the time when the fog had rolled down to the moment when, half fainting with hunger and exhaustion, I had climbed in through his kitchen window.

Leaning on the arm of his chair, he listened to me in silence. As far as any movement or change of expression was concerned a statue could scarcely have betrayed less interest, but all the time the steady gleam of his eyes never shifted from my face.

When I had finished he remained there for several seconds in the same attitude. Then at last he gave a short mirthless laugh.

“It must be pleasant to be as strong as you are,” he said. “I should have been dead long ago.”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Well, I don’t exactly feel like going to a dance,” I answered.

He got up and walked slowly as far as the window, where he turned round and stood staring at me thoughtfully. At last he appeared to make up his mind.

“You had better go to bed,” he said, “and we will talk things over in the morning. You are not fit for anything more tonight.”

“No, I’m not,” I admitted frankly; “but before I go to bed I should like to feel a little more certain where I’m going to wake up.”

There was a faint sound outside and I saw him raise his head. It was the distant but unmistakable hum of a motor, drawing nearer and nearer every moment. For a few seconds we both stood there listening: then with a sudden shock I realized that the car had reached the house and was turning in at the drive.

Weak as I was I sprang from my chair, scarcely feeling the thrill of pain that ran through me at the effort.

“By God!” I cried fiercely, “you’ve sold me!”

He whipped out the revolver, pointing it full at my face.

“Sit down, you fool,” he said. “It’s not the police.”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.