A Rogue By Compulsion (2)

By:

April 9, 2016

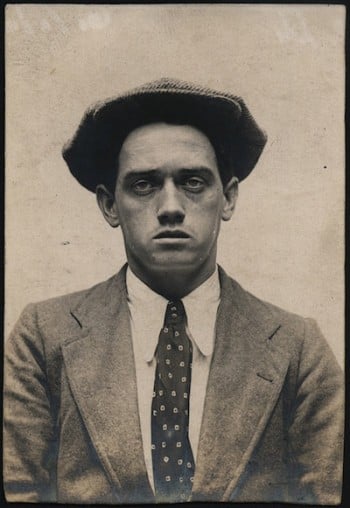

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

I was taken so utterly by surprise that nothing except sheer strength saved me from going over. As it was I staggered back a couple of paces, fetching up against the railings with a bang that nearly knocked the breath out of me. By a stroke of luck I must have crushed my opponent’s hand against one of the bars, for with a cry of pain he momentarily slackened his grip.

That was all I wanted. Wrenching my left arm free, I brought up my elbow under his chin with a wicked jolt; and then, before he could recover, I smashed home a short right-arm punch that must have landed somewhere in the neighbourhood of his third waistcoat button. Anyhow it did the business all right. With a quaint noise, like the gurgle of a half-empty bath, he promptly released me from his embrace, and sank down on to the grass almost as swiftly and silently as he had arisen.

I doubt if a more perfectly timed blow has ever been delivered, but unfortunately I had no chance of studying its effects. Through the fog I could hear the sound of footsteps — quick heavy footsteps hurrying towards me from either direction. For one second I thought of scrambling back over the railings and taking to the wood again. Then suddenly a kind of mischievous exhilaration at the danger gripped hold of me, and jumping over the prostrate figure on the ground I bolted forwards into the mist. The warders, who must have been quite close, evidently heard me, for from both sides came hoarse shouts of “There he goes!” “Look out there!” and other well-meant pieces of advice.

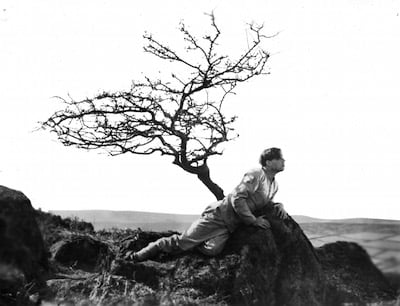

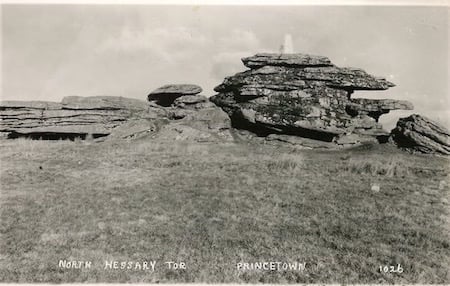

It was a funny sort of sensation dodging through the fog, feeling that at any moment one might blunder up against the muzzle of a loaded carbine. The only guide I had as to my direction was the slope of the ground. I knew that as long as I kept on going uphill I was more or less on the right track, for the big granite-strewn bulk of North Hessary lay right in front of me, and I had to cross it to get to the Walkham Valley.

On I went, the ground rising higher and higher, until at last the wet slippery grass began to give way to a broken waste of rocks and heather. I had reached the top, and although I could see nothing on account of the mist, I knew that right below me lay the woods, with only about a mile of steeply sloping hillside separating me from their agreeable privacy.

Despite the cold and the wet and the fact that I was getting devilish hungry, my spirits somehow began to rise. Good luck always acts on me as a sort of tonic, and so far I had certainly been amazingly lucky. I felt that if only the rain would clear up now and give me a chance of getting dry, Fate would have treated me as handsomely as an escaped murderer had any right to expect.

Making my way carefully across the plateau, for the ground was stiff with small holes and gullies and I had no wish to sprain my ankle, I began the descent of the opposite side. The mist here was a good deal thinner, but night was coming on so rapidly that as far as seeing where I was going was concerned I was very little better off than I had been on the top of the hill.

Below me, away to the right, a blurred glimmer of light just made itself visible. This I took to be Merivale village, on the Tavistock road; and not being anxious to trespass upon its simple hospitality, I sheered off slightly in the opposite direction. At last, after about twenty minutes’ scrambling, I began to hear a faint trickle of running water, and a few more steps brought me to the bank of the Walkham.

I stood there for a little while in the darkness, feeling a kind of tired elation at my achievement. My chances of escape might still be pretty thin, but I had at least reached a temporary shelter. For five miles away to my left stretched the pleasantly fertile valley, and until I chose to come out of it all the warders on Dartmoor might hunt themselves black in the face without finding me.

I can’t say exactly how much farther I tramped that evening. When one is stumbling along at night through an exceedingly ill-kept wood in a state of hunger, dampness, and exhaustion, one’s judgment of distance is apt to lose some of its finer accuracy. I imagine, however, that I must have covered at least three more miles before my desire to lie down and sleep became too poignant to be any longer resisted.

I hunted about in the darkness until I discovered a small patch of fairly dry grass which had been more or less protected from the rain by an overhanging rock. I might perhaps have done better, but I was too tired to bother. I just dropped peacefully down where I stood, and in spite of my bruises and my soaked clothes I don’t think I had been two minutes on the ground before I was fast asleep.

Tommy Morrison always used to say that only unintelligent people woke up feeling really well. If he was right I must have been in a singularly brilliant mood when I again opened my eyes.

It was still fairly dark, with the raw, sour darkness of an early March morning, and all round me the invisible drip of the trees was as persistent as ever. Very slowly and shakily I scrambled to my feet. My head ached savagely, I was chilled to the core, and every part of my body felt as if it had been trampled on by a powerful and rather ill-tempered mule.

I was hungry too — Lord, how hungry I was! Breakfast in the prison is not exactly an appetizing meal, but at that moment the memory of its thin gruel and greasy cocoa and bread seemed to me beautiful beyond words.

I looked round rather forlornly. As an unpromising field for foraging in, a Dartmoor wood on a dark March morning takes a lot of beating. It is true that there was plenty of water — the whole ground and air reeked with it — but water, even in unlimited quantities, is a poor basis for prolonged exertion.

There was nothing else to be got, however, so I had to make the best of it. I lay down full length beside a small spring which gurgled along the ground at my feet, and with the aid of my hands lapped up about a pint and a half. When I had finished, apart from the ache in my limbs I felt distinctly better.

The question was what to do next. Hungry or not, it would be madness to leave the shelter of the woods until evening, for not only would the warders be all over the place, but by this time everyone who lived in the neighbourhood would have been warned of my escape. My best chance seemed to lie in stopping where I was as long as daylight lasted, and then staking everything on a successful burglary.

It was not a cheerful prospect, and before the morning was much older it seemed less cheerful still. If you can imagine what it feels like to spend hour after hour crouching in the heart of a wood in a pitiless drizzle of rain, you will be able to get some idea of what I went through. If I had only had a pipe and some baccy, things would have been more tolerable; as it was there was nothing to do but to sit and shiver and grind my teeth and think about George.

I thought quite a lot about George. I seemed to see his face as he read the news of my escape, and I could picture the feverish way in which he would turn to each edition of the paper to find out whether I had been recaptured. Then I began to imagine our meeting, and George’s expression when he realized who it was. The idea was so pleasing that it almost made me forget my present misery.

It must have been about midday when I decided on a move. In a way I suppose it was a rash thing to do, but I had got so cursedly cramped and cold again that I felt if I didn’t take some exercise I should never last out the day. Even as it was, my legs had lost practically all feeling, and for the first few steps I took I was staggering about like a drunkard.

Keeping to the thickest part of the wood, I made my way slowly forward; my idea being to reach the top of the valley and then lie low again until nightfall. My progress was not exactly rapid, for after creeping a yard or two at a time I would crouch down and listen carefully for any sounds of danger. I had covered perhaps a mile in this spasmodic fashion when a gradual improvement in the light ahead told me that I was approaching open ground. A few steps farther, and through a gap in the trees a red roof suddenly came into view, with a couple of chimney-pots smoking away cheerfully in the rain.

It gave me a bit of a start, for I had not expected to run into civilization quite so soon as this. I stopped where I was and did a little bit of rapid thinking. Where there’s a house there must necessarily be some way of getting at it, and the only way I could think of in this case was a private drive up the hill into the main Devonport road. If there was such a drive the house was no doubt a private residence and a fairly large one at that.

With infinite precaution I began to creep forward again. Between the trunks of the trees I could catch glimpses of a stout wood paling about six feet high which apparently ran the whole length of the grounds, separating them from the wood. On the other side of this fence I could hear, as I drew nearer, a kind of splashing noise, and every now and then the sound of somebody moving about and whistling.

The last few yards consisted of a strip of open grass marked by deep cart-ruts. Across this I crawled on my hands and knees, and getting right up against the fence began very carefully to search around for a peep-hole. At last I found a tiny gap between two of the boards. It was the merest chink, but by gluing my eye to it I was just able to see through.

I was looking into a square gravel-covered yard, in the centre of which a man in blue overalls was cleaning the mud off a small motor car. He was evidently the owner, for he was a prosperous, genial-looking person of the retired Major type, and he was lightening his somewhat damp task by puffing away steadily at a pipe. I watched him with a kind of bitter jealousy. I had no idea who he was, but for the moment I hated him fiercely. Why should he be able to potter around in that comfortable self-satisfied fashion, while I, Neil Lyndon, starved, soaked, and hunted like a wild beast, was crouching desperately outside his palings?

It was a natural enough emotion, but I was in too critical a position to waste time in asking myself questions. I realized that if burglary had to be done, here was the right spot. By going farther I should only be running myself into unnecessary risk, and probably without finding a house any more suitable to my purpose.

I squinted sideways through the hole, trying to master the geography of the place. On the left was a high bank of laurels, and just at the corner I could see the curve of the drive, turning away up the hill. On the other side of the yard was a small garage, built against the wall, while directly facing me was the back of the house.

I was just digesting these details, when a sudden sigh from the gentleman in the yard attracted my attention. He had apparently had enough of cleaning the car, for laying down the cloth he had been using, he stepped back and began to contemplate his handiwork.

It was not much to boast about, but it seemed to be good enough for him. At all events he came forward again, and taking off the brake, proceeded very slowly to push the car back towards the garage. At the entrance he stopped for a moment, and going inside brought out a bicycle which he leaned against the wall. Then he laboriously shoved the car into its appointed place, put back the bicycle, and standing in the doorway started to take off his overalls.

I need hardly say I watched him with absorbed interest. The sight of the bicycle had sent a little thrill of excitement tingling down my back, for it opened up possibilities in the way of escape that five minutes before had seemed wildly out of reach. If I could only steal the machine and the overalls as well, I should at least stand a good chance of getting clear away from the Moor before I was starved or captured. In addition to that I should be richer by a costume which would completely cover up the tasteful but rather pronounced pattern of my clothes.

My heart beat faster with excitement as with my eye pressed tight to the peep-hole I followed every movement of my unconscious quarry. Whistling cheerfully to himself, he stripped off the dark blue cotton trousers and oil-stained jacket that he was wearing and hung them on a nail just inside the door. Then he gave a last look round, presumably to satisfy himself that everything was in order, and shutting the door with a bang, turned the key in the lock.

I naturally thought he was going to stuff that desirable object into his pocket, but as it happened he did nothing of the kind. With a throb of half-incredulous delight I saw that he was standing on tiptoe, inserting it into some small hiding-place just under the edge of the iron roof.

I didn’t wait for further information. At any moment someone might have come blundering round the corner of the paling, and I felt that I had tempted Fate quite enough already. So, abandoning my peep-hole, I turned round, and with infinite care crawled back across the grass into the shelter of the trees.

Once there, however, I rolled over on the ground and metaphorically hugged myself. The situation may not appear to have warranted such excessive rapture, but when a man is practically hopeless even the wildest of possible chances comes to him like music and sunshine. Forgetting my hunger and my wet clothes in my excitement, I lay there thinking out my plan of action. I could do nothing, of course, until it was dark: in fact it would be really better to wait till the household had gone to bed, for several of the back windows looked right out on the garage. Then, provided I could climb the paling and get out the bicycle without being spotted, I had only to push it up the drive to find myself on the Devonport road.

With this comforting reflection I settled myself down to wait. It was at least four hours from darkness, with another four to be added to that before I dared make a move. Looking back now, I sometimes wonder how I managed to stick it out. Long before dusk my legs and arms had begun to ache again with a dull throbbing sort of pain that got steadily worse, while the chill of my wet clothes seemed to eat into my bones. Once or twice I got up and crawled a few yards backwards and forwards, but the little additional warmth this performance gave me did not last long. I dared not indulge in any more violent exercise for fear that there might be warders about in the wood.

What really saved me, I think, was the rain stopping. It came to an end quite suddenly, in the usual Dartmoor fashion, and within half an hour most of the mist had cleared off too. I knew enough of the local weather signs to be pretty certain that we were in for a fine night; and sure enough, half an hour after the sun had set a large moon was shining down from a practically cloudless sky.

From where I was lying I could, by raising my head, just see the two top windows of the house. About ten, as near as I could judge, somebody lit a candle in one of these rooms, and then coming to the window drew down the blind. I waited patiently till I saw this dull glimmer of light disappear, then, with a not unpleasant throb of excitement, I crawled out from my hiding-place and recrossed the grass to my former point of observation. Very gingerly I lifted myself up and peered over the top of the paling. The yard was in shadow, and so far as I could see the back door and all the various outbuildings were locked up for the night.

Under ordinary circumstances I could have cleared that blessed paling in about thirty seconds, but in my present state of exhaustion it proved to be no easy matter. However, with a mighty effort I at last succeeded in getting my right elbow on the top, and from that point I managed to scramble up and hoist myself over. Then, keeping a watchful eye on the windows, I advanced towards the garage.

I found the key first shot. It was resting on a little ledge under the roof, and a thrill of joy went through me as my fingers closed over it. I pushed it into the keyhole, and very carefully I turned the lock.

It was quite dark inside, but I could just see the outline of the overalls hanging on the nail. I unhooked them, and placing the coat on the ground I drew on the oily trousers over my convict breeches and stockings. I could tell by the feel that they covered me up completely.

As I picked up the coat something rattled in one of the side pockets. I put my hand in and pulled out a box of wax matches, which despite the dampness of the garment still seemed dry enough to strike. For a moment I hesitated, wondering whether I dared to light one. It was dangerous, especially if there happened to be a window looking out towards the house, but on the other hand I badly wanted a little illumination to see what I was doing.

I decided to risk it, and closing the door, struck one against the wall. It flared up, and shading it with my hand I cast a hasty glance round the garage. The bicycle was leaning against a shelf just beyond me, and on a nail above it I saw an old disreputable-looking cap. I pounced on it joyfully, for it was the one thing I needed to complete my disguise. Then, wheeling the bicycle past the car, I blew out the match and reopened the door.

Stepping as noiselessly as possible on the gravel, I pushed the bike across the yard. There was a large patch of moonlight between me and the end of the drive, and I went through it with a horrible feeling in the small of my back that at any moment someone might fling up a window and bawl out, “Stop thief!” Nothing of the kind occurred, however, and with a vast sense of thankfulness I gained the shelter of the laurels.

The only thing that worried me was the thought that there might be a lodge at the top. If so I was by no means out of the wood. Even the most guileless of lodge-keepers would be bound to think it rather curious that I should be creeping out at this time of night accompanied by his master’s bicycle.

Keeping one hand against the bushes to guide me, and pushing the machine with the other, I groped my way slowly up the winding path. As I came cautiously round the last corner I saw with a sigh of relief that my fears were groundless. A few yards ahead of me in the moonlight was a plain white gate, and beyond that the road.

I opened the gate with deliberate care, and closed it in similar fashion behind me. Then for a moment I stopped. I was badly out of breath, partly from weakness and partly from excitement, so laying the machine against the bank I leaned back beside it.

Everything was quite still. On each side of me the broad, white, moonlit roadway stretched away into the night, flanked by a row of telegraph poles which stood out like gaunt sentries. It was curious to think that they had probably put in a busy day’s work, carrying messages about me.

There was a lamp on the front bracket, and as soon as I felt a little better I took out my matches and proceeded to light it. Then, wheeling my bike out into the roadway, I turned in the direction of Devonport and mounted. I felt a bit shaky at first, for, apart from the fact that I was worn out and pretty near starving, I had not been on a machine for over three years. However, after wobbling wildly from side to side, I managed to get the thing going, and pedalled off down the centre of the road as steadily as my half-numbed senses would allow.

For perhaps a quarter of a mile the ground kept fairly level, then, breasting a slight rise, I found myself at the top of a hill. I shoved on the brake and went slowly round the first corner, where I got an unexpected surprise. From this point the road ran straight away down through a small village, across a bridge over the river, and up a short steep slope on the farther side.

I took in the situation at a glance, and, releasing my brake, I let the old bike have her head. It certainly wouldn’t suit me to have to dismount in the village and walk up the opposite slope, and I was much too exhausted to do anything else unless I could take it in a rush.

Down I went, the machine flying noiselessly along and gathering pace every yard. I had nearly reached the bottom and was just getting ready to pedal, when all of a sudden, I caught sight of something that almost paralyzed me. Right ahead, in the centre of the village square, stood a prison warder. His back was towards me and I could see the moonlight gleaming on the barrel of his carbine.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.