THIS: Big Blue

By:

March 21, 2016

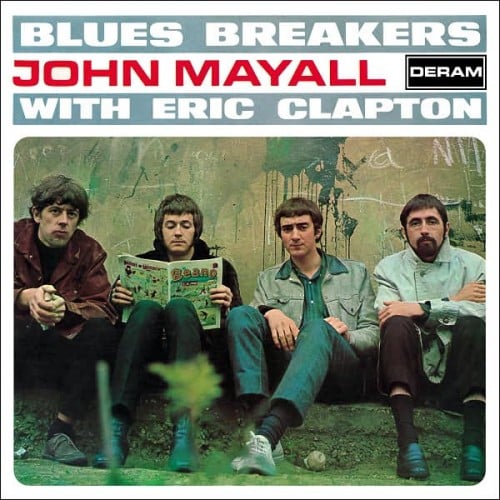

I didn’t have to know John Mayall to hate him. Figures like Mayall, Clapton, et al. were the “serious,” “real” musicians who put my glammy, synthy high-school icons to shame, and their fans with them. This of course was in the stylistically segregated mid-1970s to early 1980s, when there was no “just music” and self was defined by who you damn well weren’t. In the flower of my old age it’s clear that albums like Mayall & Clapton’s Blues Breakers were as exploratory, in their way, and in their time and cultural context, as Johnny Rotten or Bowie’s ventures to the fringe of melody and imagination and taste. Of course, roots can be less compelling than mutated flowers, which is where reincarnations like Alexis Moon and the Suns’ version of Mayall & Clapton’s foundational collaboration comes to the rehabilitative rescue. A cult supergroup, they gathered together from narrow streets converging on the Lower East Side of New York, performing that album and some kindred compositions in January of this year. Composed of neo-folk tribune and ritualistic rock diva Alexis Thomason on vocals, epicurean shredder Keith Hartel on guitar, and concussive poet Tom Shad on bass, with the thunderous percussion of Ray Kubian and, in this early gig, the multidimensional keyboard colors of Charles Roth, they crossed a horizon that kicks rock up from “classic” to mythic. In February I spoke with Thomason about their promising new past…

HILOBROW: Will you be doing other material, or did you mainly convene to be the re-creators of this particular canon?

THOMASON: Our idea with this project originally, it wasn’t a Blues Breakers project initially, we wanted to put together a psychedelic rock band that was doing… not what the jam bands are doing. We wanted to do improvisatory rock; my want was to do stuff that was a little heavier, Tom’s idea is to do stuff that’s a little more avant-garde, just a little more weird, and Keith Hartel, he and I agree a whole lot on taking psychedelic rock from the heavier approach, and where this all sort of meets is in the heavy blues, and things like early Floyd, and Hawkwind, and those are the kind of things that we were talking about early on. And we all come from this tradition of doing album nights; that’s kind of how we met, doing these tributes. Well, that’s how I know Keith; I’ve known Tom for 20 years, mostly from jazz. We did a Husker Du tribute, a couple of Bowie tributes, and Keith is really good at picking albums, and we wanted to pick an album and assemble our “dream band.” Keith’s idea, which won, was the Blues Breakers album.

HILOBROW: It’s funny that you said you wanted to do something heavier, because I was surprised, when I did listen, at long last, to the actual album, at how…relaxed some of it sounded, even though it builds in intensity as it goes, and it’s almost as if you have to have lived past the punk era to bring the kind of ferocity that you guys do to it.

THOMASON: We’re all post-punk and they weren’t, so there is that. Although that album is thought to have started a whole subgenre of riff-heavy rock, like Zeppelin and Cream. Clapton was on the verge of thinking about that kind of stuff. These guys all just kinda know each other. The Mayall [material] is a lot “mellower,” but not really — it doesn’t use the heavy distortion, but it does have this authentic blues vocabulary… John Mayall wasn’t playing with the blues, he was playing The Blues. It’s this road to doing seriously deep blues. So that’s why it feels heavier to me.

HILOBROW: Do you make that assessment based on a knowledge of its context and its immediate predecessors, as much as, maybe, its own intrinsic qualities?

THOMASON: Both. We have the virtue of historical hindsight, but it’s also…it’s 1966, and it’s one of those albums from 1966, so it’s this crossover into something very different from what everyone was doing. And people went in a lot of different directions; the Beatles went psychedelic, and lots of people stopped “writing songs” and started making albums, and others started to make their blues more blues, and more riff-heavy, and everything was like on this crux.

HILOBROW: It reminds me of the way that something like “God Save the Queen” sounded like a clatter when it came out, and by a decade later it sounded like the perfect pop song it is, and the Dead Kennedys’ “Holiday in Cambodia” sounded like a pop song by the mid-1990s, even though it had sounded even more harsh and aggressive than the Pistols at the time, but this is based on what preceded each. It’s interesting, when those trappings of stylistic reference fall away. Do you think sometimes it’s easier to perceive the merits, and even the characteristics of certain music at that kind of historical remove? Because you seem to tap the roots of this music better than bands in the intervening generations might have, because they were revisiting it instead of re-creating it. An album like this can be thought of as a signifier for anti-theatrical, meat-and-potatoes rock, whereas you guys seem to tap the common furious wellspring of it.

THOMASON: I’m glad that that’s what’s coming across so far. We had a fairly distinct idea that we didn’t want to be just like any old cover band… for my part, I always feel like I’m in a particular place where I can re-create something from my vantage-point because I’m female, doing what is considered male music. And I’m very meta about that. Sometimes I will change lyrics, and sometimes I won’t. It depends on what it is contextually. I consider any text that I sing to be a monologue; I consider the pronoun usage, and I will purposefully change pronouns, or not, given the meter, the context, and also what it is I’m saying, because we are living in a time when women can sing about other women, and about men, and one woman can sing about either. It’s important for me to be able to relay the character’s story of whatever song I’m singing. I’m very thoughtful about singing someone else’s song.

HILOBROW: I was going to ask if this project was, in some ways, a repair of history, and if a feminine presence was what might have been missing.

THOMASON: Relationship dynamics and politics go hand-in-hand for me, because I’m a female, and I’m a feminist, and I’m in a rock’n’roll world that is mostly dominated by men, still to this day — even if women are ruling the pop world, they’re not ruling the rock world.

HILOBROW: I’m reminded that there were always top-rank icons of the blues itself who were women, but then it was pretty much re-taken over by men for the rock incarnation.

THOMASON: I’m glad that you bring that up, because I once did a big thesis on the African-American blueswomen of the 1920s, ’30s, going into the ’40s, though they were starting to morph into different things because of the Depression and the Swing era, and comparing them to the white women who were doing the folk tradition, which musically are not dissimilar, y’know, the mountain music of the South is not dissimilar from the blues music of the South; there’s maybe a different rhythmic emphasis, but it comes from a very similar place. But the African-American women had a lot more freedom to be bluesy, raunchy, because they were already living outside a certain kind of society. And white women didn’t have that option, so they went more the route of — well, you hear it in the Carter Family — they went more the religious route… though the Carter Family is an interesting exception because they did do some blues. They kind of got away with doing some blues, and a lot of white women did. And obviously African-American women were also involved with creating what would be Gospel, coming from the hymn tradition. Other people wanted to make these categories, but all these women were singing deeply religious and deeply raunchy music [laughter]; the musicians didn’t want to categorize themselves.

HILOBROW: Some becoming a woman without a country, like Rosetta Tharpe — cast out of the church, while she was singing only about Jesus.

THOMASON: The classic blues singers, Bessie Smith being the pinnacle, there was so much great stuff in that period, late ’20s, early ’30s, up until they couldn’t do it anymore, because it got too expensive for them to tour on these really, really segregated tour routes that they had to deal with. But yeah, the white women who sang the blues in rock, Janis Joplin being the most well-known, adored these women; this is what they were all listening to… but there’s not a lot of women from that time period, in rock — there still were quite a lot of women in jazz but not as many as men. Like anything else, there were ceilings that women had to deal with, and reputations, and shaming, and just the typical, natural things of, like, “I’m gonna get married, and have a baby now, and spend a lot of time that I would normally be working on my career, having a family.” But even if women’s voices in numbers might have been missing, the ones who were doing it were loud. Because when you’re in the minority, you get loud.

Somebody might look at the kind of music we want to do for this band and be like, “That’s guy music,” and I do sing a lot of, y’know, maybe “guy” music, but for the reason that Patti Smith I think sings a lot of “guy” music, which is that, I’ve been influenced by rock’n’roll, we’ve all been influenced by male musicians ’cuz that’s what there was to listen to. So, do I like it because it’s a guy thing or do I like it because it is in fact cool? I’m gonna say on the record right now that I don’t think I like Led Zeppelin because it was a bunch of guys, but because they were fuckin’ cool — they could’ve been women, if anyone plays like THAT I’m gonna think they’re cool. Do I like it because it’s men? No. Do I like it because there’s an aggressive, masculine thing to some of this stuff? YES. Which is different; that’s very different to me.

HILOBROW: It’s a question of which comes first, the man or the association, because it seems to me that there is an affirmative aggression, that is accessible by anybody, but got assigned to, associated with men, because they had the agency to exercise this. I was a big metal fan in high school, and still like a lot of it, but I find it in places where metalheads don’t think it is; “Don’t Make Fun of Daddy’s Voice” by Morrissey is clearly a metal song, but no metal fan would claim it… but I realized that that energy I would get from your Priests and your Maidens and your Dios is still there in a lot of music I listen to, but it’s almost exclusively by women — Rasputina, Skin from Skunk Anansie — I want that psychotic aggression, but it only seems pure from women singers and players, and I think that’s because it isn’t a gendered thing; it’s a lifeforce which sometimes is actually obstructed by males, because we trivialize it down to just being about “power.”

THOMASON: Oh, women are ferocious; like I said, we know we have to get loud sometimes. Because we can’t rely on an ability to stop something with our hands, we have to rely on our ability to stop something with our voice. This reminds me also that, men suffer from these gender roles just as we do, but the men in the ’60s — now we’re talking about, “Well if you like rock’n’roll, you just like ‘man’ stuff,” but the men of the ’60s, they were called “fags,” they were dissed for their long hair and their boots and their tight jeans, and wearing blouses; all of these men were dealing with the idea that… they were playing with gender roles, whether they were identifying as… I mean, nobody was really comin’ out of the closet back then strongly — not in [mainstream] rock’n’roll. But that leads to… y’know, we’ve all lived through, now, Bowie’s lifetime, right? We’ve all seen this arc of exploration, and we are so lucky, like Simon Pegg said, to have been on this planet during that. And now we can do whatever we want. I can play whatever role I want to play onstage. And it’s a lot due to the men of the ’60s saying, “I’m gonna let my hair grow long. And hell, if I let my hair grow long, why can’t I wear a dress on my next album.” They were playing with that line between masculine and feminine, and that’s what I’m doing, although maybe it looks like I’m just standing up there and singing a song but I’m thinking about that, and I hope it does come across.

HILOBROW: It does. When I saw you sing two songs from Ziggy Stardust [in 2015], I felt that the pure essence of the Ziggy avatar had passed from Bowie to you.

THOMASON: That’s a compliment that’s almost too nice and I’m not sure I can accept it, but thank you.

HILOBROW: Maybe only women can sing that material now; I saw Gail Ann Dorsey on the Suffragette Sessions tour and it was the best version of “Ziggy Stardust” ever done! And you raise an important point; it’s become so engrained that it had receded into the mists of history for me, the representational risks that male rockers in the ’60s were taking. An interesting dichotomy, since they were taking that risk at the same time they were appropriating black music… and Little Richard was living that gender-fluidity too, while he couldn’t get played on white radio… but with the Brits [the appropriation] was always a bit more removed; it wasn’t personal, in the way that it was with Elvis…

THOMASON: That’s true. The British have… I keep bringing it back to theatre, but so much of singing, for me, has become very theatrical, because I have done so much opera and theatre in the last ten years, and it’s changed who I am as a singer, dramatically. I was singing rock and blues and folk and jazz before that for a very long time, but then I started to do theatre, and started to think about how I portray songs in a very different way. The British have the theatre tradition, and they’re not afraid to be presentational about it. The United States is more known for its movies; we’ve got the classic Hollywood tradition…

HILOBROW: …We’re also insistent on our “sincerity” and “authenticity”…

THOMASON: …Yeah, we’re the Method-y ones. British bands weren’t afraid to be theatrical. Not to say American bands didn’t take that on. All the British stuff fed [back] into the American stuff, and what came of that? New York Glam; the New York Dolls and all that.

HILOBROW: That theatricality, that switching of roles, might be the key to something that still blows my mind — I have living memory of when a high school John Mayall fan would have to change his name and enter the Witness Protection Program if he became a Bowie fan, and vice-versa; there was this stylistic sectarianism that seems to have completely disappeared. What is the yardstick for an artist like you?

THOMASON: You probably lived through more of that “these guys versus these guys” stuff than I did.

HILOBROW: I’ve always maintained that four years is a pop-culture generation in America, so I’m two “generations” older than you.

THOMASON: By the time I was in high school, there was still the subgenre vs. subgenre thing; the skinheads and the metalheads didn’t hang out together… I came into high school really liking metal; I listened to my dad’s music and I loved the Beatles and Stones and classic rock, because I grew up with that; those are like my lullabies, my nursery-rhymes. But as I started to pick my “own” music, it was like Metallica, and Megadeth… and before that it was really shitty stuff that I don’t even want to admit to… every 13-year-old girl in my age group had to like Poison, and Bon Jovi — it had to happen, it was gonna happen and it happened. And then it stopped happening, so it’s okay [laughs]. I liked thrash metal, speed metal, and that stuff got me into Misfits, then I started to get really political and get into punk rock, and then it was all over for me… when I first got to high school I was a stupid little freshman, and maybe for a second I cared about, “oh, the skinheads don’t like me,” and “I guess I’m this”; then I started smokin’ pot, and doin’ acid, and listening to Mike Watt, and I didn’t care about ANY of that shit anymore [laughs], I cared about peace and love and any music I could get my hands on that wasn’t telling me I shouldn’t listen to other music. I love music, all of it.

HILOBROW: What would be the criteria for music you wouldn’t like?

THOMASON: Safe music. Why make art if you don’t have something to say. Art can be just beautiful and pretty; art can be just ugly; it can be a combination of the two in different tensions and releases; but if you don’t have a viewpoint, find your viewpoint. I never begrudge anybody making something — everybody is in-process, [so] just… try again. Raise the stakes. If what you’re saying has been said a million, trillion times and there’s nothing new about it, raise the stakes. You’re out there making art because you have some need to; what is that need? Tap into that need to do it, and say what’s there in that need. You don’t have to answer the question, you just have to pose the questions; there are no “answers,” pose the questions; that’s so much more interesting than “having the answers.” If you already have the answer why even ask?

HILOBROW: It’s about knowing what to look for, or what direction to look in. One thing that ties into that performative, and classical-music-world model is… I hear younger people be sheepish about only knowing isolated songs from YouTube, and older people demanding that their kids only buy whole albums to get the artist’s “statement,” but… the LP era is an anomaly; people listened to singles from the advent of recording to the beginning of the ’60s almost, and now we listen to just single songs online again —

THOMASON: Not me.

HILOBROW: [laughter] Well, hence my question: It seems to me that it’s only post- the album era that we see people, very commonly, do full albums, almost like a concerto, a symphony, as a single concert; whereas the artists themselves who are being homaged, in their time they would just do an assortment of their hits and their favorite songs from many of their albums.

THOMASON: I think that a lot of current artists are very interested in thematic work. Beyoncé has proven that she’s interested in that… I’ll admit to knowing Lady Gaga singles better than I know Lady Gaga albums, but I see recurring themes in her work, which makes me think she’s interested in what the album says. I think there’s a lot of people who are interested in what albums are still capable of doing — and even going past what albums have traditionally done.

To hear what Alexis Moon and the Suns do next, visit their ReverbNation page.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE