10 Best Adventures of 1921

By:

February 16, 2016

Ninety-five years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Nineteen-Teens Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

In no particular order…

- Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne’s frontier adventure Messer Marco Polo. An elderly Scotch-Irish bard — in modern times — tells a lively tale, to his young American nephew, about Marco Polo, an Italian Catholic explorer journeying across Asia from Venice to the courts of Cathay in pagan China, during the High Middle Ages. Though sent as a kind of missionary — after an audience with an Irish pope — when Marco Polo visits the court of Kubla Kahn, the Mongol ruler and emperor of China, he falls in love with Golden Bells, daugher of the Khan. Their love story is lyrical and sweet, but the book is very much an adventure, too. The caravan is lost in the Gobi Desert; there is murder and witchery. And the amused politeness with which Marco Polo’s preaching is met is wicked! Fun fact: Often categorized as a children’s book, but in fact it’s Menippean satire. The multi-layered, historical/fantastical, ironic/romantic quality of this yarn brings to mind Donn-Byrne’s contemporary, James Branch Cabell, who called this “a very magically beautiful book”; as well as Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds or William Goldman’s The Princess Bride. Donn-Byrne died tragically young, in 1928, in an automobile accident.

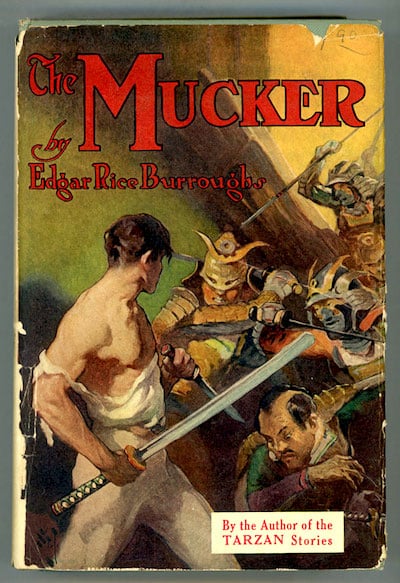

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s picaresque The Mucker. Framed for murder, a young thief and mugger flees to San Francisco, where he is shanghaied. Forced to labor on a vessel headed to the Far East, Billy’s attitude and behavior begins to change for the better. When the ship founders, he helps land it — and rescues Barbara, a kidnapped heiress from pirates. She is then snatched by Malaysian headhunters, so Billy rescues her again… and then protects her in the jungle, where she teaches him how to speak properly. (There’s a Tarzan/Jane dynamic at work.) Billy then sets out to rescue Barbara’s father and fiancé — and nearly dies in doing so. He eventually returns to America, where Barbara seeks him out… but he won’t marry her! At least, not until he proves himself innocent of murder. Fun fact: First published in All-Story Weekly in October and November 1914. In his 1965 book Master of Adventure: The Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Richard A. Lupoff calls this novel “a most remarkable technical achievement,” because it is “virtually a catalog of the pulps.”

- Frigyes Karinthy’s Capillaria (1921). Gulliver, protagonist of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, who in Karinthy’s 1916 Voyage to Faremido: Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage (1916) visited a planet of intelligent machines, now finds himself saved from drowning in an underwater empire ruled by women. The males (“bullpops”) of this planet are fighters and builders, creative and rational… yet they are dominated by the emotional, illogical womenfolk. Not only do the women of Capillaria devote themselves entirely to pleasure, and tear down the (phallic) towers erected by the men, but they feed on the brains of their menfolk! A misogynistic adventure influenced by August Strindberg, who often made pronouncements like, “Woman, being small and foolish and therefore evil… should be suppressed, like barbarians and thieves.” Fun fact: Karinthy’s fifth and sixth journeys of Gulliver’s aren’t the earliest example of Gulliveriana — but they’re among the most influential.

- John Dos Passos’s WWI novel Three Soldiers. Although Three Soldiers is set in Europe, during World War I, it’s not exactly a military adventure. We get no sense of the horrors of front-line combat, here; instead, we are confronted with the corruption, cruelty, futility, and absurdity of military life. Chrisfield, an Indiana farm boy, is a cretin who detonates grenades for pleasure, and is always spoiling for a fight — with his fellow soldiers. Fuselli, a simple-minded Italian American, hopes to earn a promotion and achieve a better life after the war; instead, he is assigned to demeaning, pointless drudgery. Andrews, finally, is an idealistic Harvard graduate and would-be poet; he is particularly sensitive to the numbing, coarsening effects of Army regimentation and discipline. Other soldiers, meanwhile, are portrayed as mercenaries, hustlers, and sociopaths! Fun fact: During WWI, Dos Passos was a member of the American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps in Paris and in Italy, later joining the U.S. Army Medical Corps. According to H.L. Mencken, the realism of Three Soldiers “disposed of oceans of romance and blather. It changed the whole tone of American opinion about the war; it even changed the recollections of actual veterans of the war.”

- Rafael Sabatini’s historical adventure Scaramouche. When a cynical young Breton lawyer, Andre-Louis Moreau, denounces the aristocracy — this is shortly before the outbreak of the French Revolution — in front of a riled-up crowd, he becomes a wanted man. He joins a troupe of travelling Commedia dell’Arte actors, assuming the stock character of Scaramouche — a scheming rogue who clownishly burlesques his aristocratic superiors. However, Moreau’s true identity is discovered and he is forced to go into hiding. He bluffs his way into an apprenticeship with the Master of Arms at a fencing academy — and, over time, he becomes a dangerously skillful swordsman. During the Revolution, Moreau emerges from hiding and goes into politics… he has become an idealist! However, he must fight a duel to the death with an old adversary. Fun fact: Scaramouche was worldwide bestseller for Sabatini, rivaled only by his other adventures, including The Sea Hawk (1915) and Captain Blood (1922). The novel was adapted into a 1923 swashbuckling movie starring Ramón Novarro.

- H. Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain adventure She and Allan. Haggard, the king of sequels, here writes what is almost a piece of fan fiction, one which unites characters from two hugely popular earlier novels of his. Hoping to communicate with deceased loved ones, the English-born professional big game hunter Allan Quatermain (from Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, 1885) seeks out a great white sorceress who rules a hidden African kingdom. On the way there, Quatermain meets a fearsome Zulu warrior chieftain, Umslopogaas — who, by the way, will become a recurring character in future Haggard adventures. Quatermain and Umslopogaas seek to rescue a beautiful European girl from a tribe of cannibals, and the chase takes them to the ruins of the ancient city of Kôr… where dwells Ayesha, the immortal enchantress (from Haggard’s She, 1886). Ayesha enlists Quatermain and Umslopogaas to lead her warriors against the forces of Rezu, a fearsome upstart. Oh, and Allan communes with the dead! Fun fact: She and Allan is an early example of a prequel; it takes place before the events of King Solomon’s Mines and She. The character Ayesha was a hugely influential one: C.S. Lewis patterned the White Witch on Ayesha; and Tolkien’s Galadriel is a version of She, as well.

- Louis Joseph Vance’s crime adventure Alias the Lone Wolf. In this fourth installment in Vance’s popular Lone Wolf series, Michael Lanyard — who, in the first book was a master thief, and in the second a freelance adventurer, and in the third a British secret agent — is feeling his age. He’s nearly 40, and his previous adventure (1918’s Red Masquerade: Being the Story of The Lone Wolf’s Daughter) was stressful, since it meant rescuing his grown daughter from murderous Bolsheviks. The Russians are now searching London for him, in order to exact revenge. So Lanyard heads to southern France. Alas, when he rescues a beautiful woman from highway bandits, his idyllic retirement is interrupted. In order to save an innocent man framed for burglary, he must pit his wits against a fiend. Lanyard must once again become… The Lone Wolf! Fun fact: Vance wrote eight books in this popular series, ending with The Lone Wolf’s Last Prowl (1934). Some two dozen silent movies featured the character, as well: from The Lone Wolf (silent, 1917, starring Bert Lytell) to The Lone Wolf and His Lady (1949, starring Ron Randell).

- Eleanor Marie Ingram’s occult adventure The Thing from the Lake. On his first night at his new weekend retreat — a broken-down farm, on a “swamp-lake” in rural Connecticut — New York composer Roger Locke wakes up to find a strange young woman in his bed. She urges him to leave this terrible place; she also refuses to allow him to turn on the lights while she’s in the room. Later, an inhuman thing from the lake will attempt to break Locke’s will and claim his soul… or is he just imagining things? Enthralled by the mysterious woman, Locke enlists his cousin and her husband to fix the place up. Every time he stays at the farm, he encounters the woman — who, it seems, may be the same woman who lived on that property over a century ago, and made a pact with the Devil. Is she trying to help him escape — or is she in league with the thing from the lake? Fun fact: Ingram was a successful novelist, known for The Flying Mercury (1910) and The Twice American (1917), when she wrote this, her first occult thriller. She died soon after its publication, at the age of 34.

- Ben Hecht’s comical adventure Erik Dorn. Before he became the Hollywood screenwriter famous for Scarface, The Front Page, Some Like it Hot, and His Girl Friday, Hecht wrote a novel in which a cynical, burned-out Chicago journalist abandons his wife (and his mistress, too — the novel’s sexual explicitness made it a sensation, at the time) for the excitement of revolutionary Europe. In post-WWI Berlin, Dorn seeks to become a participant rather than an observer in life. However, Erik Dorn is a sardonic inversion of a self-liberation adventure; nothing works out, for our would-be hero. Upon returning home, Dorn finds his wife re-married… and he no longer cares for his mistress. He is even more hollowed-out than before he left. Fun fact: The novel is semi-autobiographical. After World War I, Hecht was sent to cover Berlin for the Chicago Daily News.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1921). This dystopian novel, set in a totalized social order whose citizens (“ciphers,” with numbers for names) eat, sleep, work, and even make love like clockwork, extrapolates from the rhetoric of those communists who advocated extending Taylorism and other capitalist scientific-management techniques beyond the factory into all spheres of life. Their ancestors were right to invent a more equitable social order, the female revolutionist I-330 tells D-503. But afterward, she adds (speaking in a mathematics-inflected register intended to subvert D-503’s lifelong conditioning) “they believed that they were the final number — which doesn’t exist in the natural world, it just doesn’t.” Fun fact: We circulated in samizdat for years — in which form it influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Reissued by Penguin Classics.

Let me know if I’ve missed any 1921 adventures that you particularly admire.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.