Dada Entry

By:

November 16, 2015

Nord Hausen Fly Robot (invisible republic #3)

Adapted, designed, and directed by Ian W. Hill

Assisted by Berit Johnson

Some music by David Finkelstein

Some music by Anna Stefanic

The Brick, Brooklyn, USA, Nov. 12-21, 2015

Freedom is a collaborative work, and just because some of its artisans are anonymous doesn’t mean they don’t want their work known.

Nord Hausen Fly Robot (invisible republic #3), the latest theatre event by Gemini CollisionWorks, a partnership known for its cultural collages of found texts and disjunctive but orchestrated staging, is the company’s rare show that comes pre-randomized — Nord Hausen’s title and libretto are taken entirely from an already-folkloric (and untraceable) internet screed. Presumed to be the work of a neurodivergent writer with possible oracular, associative insights (or at least perspectives) on the geography of American pop and political culture over the past century or more, the text is a seizure of buzzwords about overstepping leaders and both rebellious and conformist art.

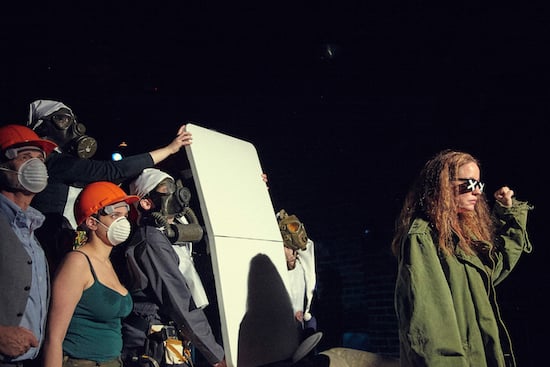

Director/adaptor Ian W. Hill and assistant director/stage manager Berit Johnson tend to cast in clockworks of crowded dramatis personae, who counterpoint each other in intricate yet immediate webs of voice and choreographed interaction. Nord Hausen has an onstage cast of ten, characterized like a Fisher-Price toy set of occupations and social roles, perhaps to mirror the multiplicity of possible identities the unknown essayist might possess.

The cast maintains an inspired ensemble panic, the deranged word-association distributed amongst them as its context shifts with their assumptions of dress-up personae and differing inflections as patriarchs, beauty queens, revolutionaries, corporate propagandists, unheeded prophets.

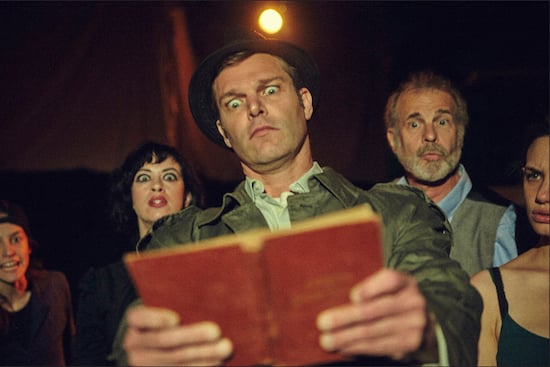

The undifferentiated flood of political fighting-words and pop-culture references mirrors the unsiftable sea of surveillance-data that is supposedly defining and defending us. The proclamations, like one half of a conversation with an unseen cellphone partner or a voice even deeper inside your head, are a pantomime of dread, detached from any specific reason except for the keywords of social anxiety — “Nazi,” “Hitler,” “torture,” “drone” — that cycle like an incantation, accentuating their dominance in the public mind while obliterating coherent understanding. Even so (as with Gore Vidal’s Saint Timothy being prepped by religion’s arbitrary logic to make sense of American TV shows beamed from the future), the ritualistic repetition of Nord Hausen opens windows on certain associations, like entering an ecstatic state of speaking (or speech-ing) in tongues.

It’s madness set to visual music, with the stage a strange loading-dock of different levels: a cage-like catwalk on one side; a barren enclosure (wallpapered with unreadable newsprint journalism and with one small window-space) in which the performers gather like some holiday dinner you’re not invited to (and from which they sometimes broadcast onto monumental bedsheets from a concealed camera); a platform on that structure’s roof that represents a radio studio from which players alternate as chorus and control-voice. Around the stage’s ground level, several mics are set up, for characters to temporarily declaim, through a now nostalgic technology, on politics and culture and freeform anxiety the way that people in the current “real” world each have their own unlimited small-screen time.

Other archaic tech — bare lightbulbs, rotary phones — speckle the set; Hill’s ingenious sound-design, a constant shuffle of TV news and primetime-entertainment noise, includes excerpts from one of the helpful guides on how to act in a nuclear holocaust that were recorded by mainstream-media father figures of midcentury America (in this case, Art Linkletter); he advises you to leave the phone-lines open, and in a hilarious recurring gag, several characters simultaneously answer ringing phones which then play this reminder, Simon-Says-ing them back into submission.

Ephemeral demarcations, like the arbitrary borders of nations, periodically dismember the set; lines of tape stretched across a window; thin filaments strung across the stage with keepsake photos of celebrities hanging like holiday-cards or prayer-flags; rolls of crepe crossing like the strands of a maypole hopelessly tangled.

The spoken text is choreographed, later in the play, as a swirl of assassinations, often of the same people serially, that register about as seriously and lastingly as shoot-downs in a videogame; still later, we see a series of Jonestown-style kool-aid toasts and other group death-pacts; the progression from the Vietnam era’s mass murder to more modern, passive mass suicide is satirized all the more distressingly for its detachment.

That disconnection is infectious; at times the dialogue is drowned out, and occasionally words are live-bleeped (even this freeform mania is subject to redaction), but just as much when, as is usually the case, you can hear it, the speech often blends into a pure psychobabbled soundscape, like cultural background radiation — confounding attention while rewarding imposed interpretations.

You can’t tell the “good” guys from the bad, but you can tell the players from each other — personality is the last redoubt of individual choice, even if the author of the play’s source-screed eschewed this existential comfort. Linus Gelber is antic and incandescent as a desperately game apologist for the system; Alyssa Simon radiates dignity and haunted urgency as a baffled yet intoning street-bard; Amanda La Pergola is hilarious and unsettling as a self-besotted celebrity/authority figure who speaks her allotment of the manifesto as if lines in her own language have been memorized phonetically (and, later, takes on the brief life of a terminal Southern belle declaiming in a Lincoln beard ’n’ stovepipe). Olivia Baseman is walking-deadpan as a cold-war spy/corporate-predator type in a series of goth cocktail attire and neo-’80s absolute-power suits; Lex Friedman overthrows all of her scenes as an unassailably deluded insurgent, expertly negotiating the attitude that hysteria itself intensifies the importance of her exclamations, like the archetypal American abroad who thinks the locals will understand more the louder you talk.

A few of the unknown essayist’s separate works (as identified by Hill and Johnson) are added as the lyrics to original songs; people burst into musical numbers in real life now and we have the internet to thank, so why not onstage too like they always did? The masses need diversion and so does the social system; hegemony won’t keep working if the higher-ups aren’t hearing any singles.

Johnson herself at one point toward the end descends from her sound and lighting board to deliver some of the shadow-prophet’s words (in-between issuing tech cues to an unseen counterpart), in an absurd, heartbreaking aria (set, as are all the songs, by David Finkelstein). Even Simon’s sage falls into reverence, to see a fourth-wall-breaking figure from a layer of unreality still higher than the stage-set’s radio booth. The text ends with inconclusive P.S.’s and See-Also’s to hold the floor; even the apostate author can be awed, and in the absence of any assured deliverance, we all at least have the option to stay tuned.

photos: Mark Veltman