Taking Sides

By:

November 9, 2015

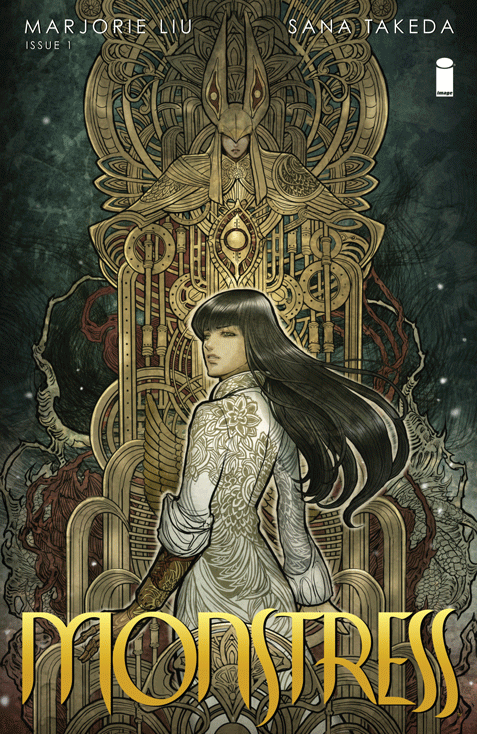

Monstress Issue #1, by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda, Image Comics.

For those who have lived a life of comfort, or reasonable shelter, or empowering challenge, the sufferings of the world can seem unreal. For those who’ve lived through loss, abuse, war, disease, on a personal or mass scale, the everyday wonders of a quiet, creative life are what seem like the fantasy. Those who stand across both, hearing the stories and possibilities of each, are the ones whose souls and psyches are not divided, but complete.

Monstress takes place in the twilight states on either side of that divide, and follows the people lost within them. It’s a fairytale as bloody as the ones from our harsh, pre-modern folk culture, before collectors sanitized them for those in comfort and left the tellers and their uncomfortable world behind. Women spoke most of those stories and men rewrote them and took credit; we see mostly women in Monstress, but the promise of utopia based on who you happen to be like is one the creators don’t allow themselves to trust in — showing instead how all humans (all beings) separate themselves and narrow that definition.

The book’s world could be a dim antiquity or a distant future, or the shadow cast by earthlings’ perpetual cruelty and wrong lessons learned. We’re in the opulent surviving cities and emotional ruins of a war between a sorcerous matriarchy and an inherently magical underclass — the Cumaea are high-tech alchemists while the Arcanics are rustic beings of strange changeling power… a kind of scientific-First-World/agrarian-Third-World schism, though outsiders may wonder what’s so different between these “witches” the Arcanics hate and these spirit-beings the Cumaea disdain and exploit. Hutus and Tutsis, Serbs and Croats, knew an Other when they saw one (and stopped seeing humans), and that’s all anyone needs.

In a short back-page essay, writer Marjorie Liu notes her family history in the ravages visited by World War Two upon China (her insightful collaboration here with a brilliant artist from Japan, Sana Takeda, is a new chapter in itself) — but the whisper of warfare and abomination in Monstress is much nearer in time and closer to our submerged consciousness than even that conflict. Though the book is staged in fanciful settings, the shadows of Abu Ghraib are long and deep over the sadistic yet offhand dungeon-drones seen terrorizing captives in Monstress, and the unspoken wars of the powerful against the vulnerable, the unvalued victories of those who find strength in survival (from disaster, rape, domination) are the scarcely concealed subtext of this book’s tension and melancholy.

Maika, an Arcanic and, at age 17, former slave, with ominous but undeveloped telekinetic skills and a murderous mission inside her enemies’ gates, is as unrepentant an insurgent as the ruling elites of the Cumaea are indifferently cruel… though each is driven by a wartime loss and pain that obliterates its own chances for healing. Though Maika’s is our point of view, we watch the mutual struggle like peasants seeing fighter planes speed by, or kids cowering while one parent beats another; invested but voiceless in the outcome, and not sure if survival is even among the choices.

Discorporation is a recurrent theme — many characters are missing limbs, and the two lands, once upon a time tolerant if not allied, are severed by barricades and an uneasy stalemate. We know, in our reality, of the children’s hands lost for diamonds on First World fingers… there are monsters hiding in many of us, and are we also monsters for what truths and trials we hide from?

The monsters of the title are of course literal too — this is fantasy, and the Cumaea fear that the Arcanics can conjure godlike destructive beings; the Arcanics hope they’re right but hardly believe it themselves. Liu’s endnotes ponder how monstrosity done to someone, or whole cultures, can be stopped from breeding just more of it in oneself. But many victims of violence identify as figuratively or literally misshapen; their fear of themselves is their oppressors’ victory.

The subjectivity of Monstress is what transcends the tropes that Liu and Takeda have reclaimed. We feel the doom and hurt of so many discarded war-casualties and dungeon-dwellers (especially the unlucky, intrepid ones who live), figures so often mere background-props to medieval kitsch, fetish-pop, and the everyday existence of the privileged or the dutifully silent.

Liu’s writing is a poetry of the honest; the speech coarse and miraculous by dizzying turns. The story unfolds at a dreamlike pace, inescapable but propulsive. The characters may not be locked forever into the now they’re experiencing, but we will drag through it with them step-by-step; the eternal immediacy of fable keeps it all horrifically involving. Takeda’s art seems sketched from life in another dimension; staggeringly grand fantasy capitals and desolate wastelands, intricate cultural detail and eloquent expressive figure and facial work; the whole book looks cut from crystal and gold that shifts shape like a magic mirror’s anime — the modern form of fairytale that Takeda takes her fallen characters’ look from, and then takes through the ordeal of a tarnishing reality.

Those old folktales were the frightened testament of a world whose origin and workings were murky; Monstress is the anxious kind of fable told in a world whose future, not past, is what’s cast in shadows. In this darkness it’s a text that burns, and shines, and knows what’s there to be afraid of, and takes steps forward all the same.