When the World Screamed (7)

By:

October 26, 2015

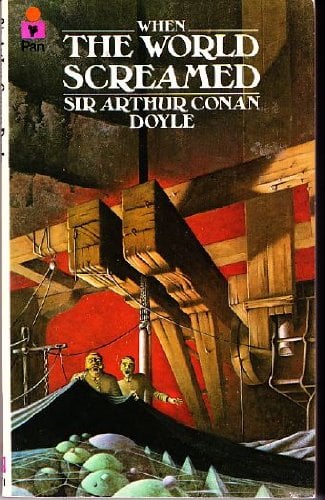

Arthur Conan Doyle’s novella When the World Screamed was first published in 1928. The fifth and final Professor Challenger adventure, it takes us not outward (e.g., to a South American plateau crawling with dinosaurs), nor inward (e.g., to an airtight chamber, while the Earth passes through a poison belt), but instead downward. Challenger, here described as “a primitive cave-man in a lounge suit,” while also “the greatest brain in Europe,” proposes to drill his way from a tract of land in Sussex (England) eight miles beneath the planet’s epidermis. Why? In order to prove his hypothesis that the world is itself a living organism! Enjoy.

‘What is that light?’ I asked.

Malone bent over the parapet beside me.

‘That’s one of the cages coming up,’ said he. ‘Rather wonderful, is it not? That is a mile or more from us, and that little gleam is a powerful arc lamp. It travels quickly, and will be here in a few minutes.’

Sure enough the pin-point of light came larger and larger, until it flooded the tube with its silvery radiance, and I had to turn away my eyes from its blinding glare. A moment later the iron cage clashed up to the landing stage, and four men crawled out of it and passed on to the entrance.

‘Nearly all in,’ said Malone. ‘It is no joke to do a two-hour shift at that depth. Well, some of your stuff is ready to hand here. I suppose the best thing we can do is to go down. Then you will be able to judge the situation for yourself.’

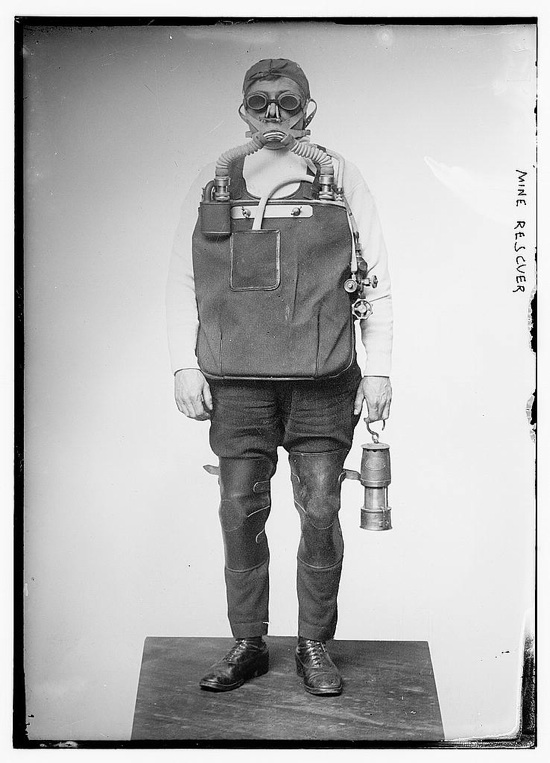

There was an annexe to the engine-house into which he led me. A number of baggy suits of the lightest tussore material were hanging from the wall. Following Malone’s example I took off every stitch of my clothes, and put on one of these suits, together with a pair of rubber-soled slippers. Malone finished before I did and left the dressing-room. A moment later I heard a noise like ten dog-fights rolled into one, and rushing out I found my friend rolling on the ground with his arms round the workman who was helping to stack my artesian tubing. He was endeavouring to tear something from him to which the other was most desperately clinging. But Malone was too strong for him, tore the object out of his grasp, and danced upon it until it was shattered to pieces. Only then did I recognize that it was a photographic camera. My grimy-faced artisan rose ruefully from the floor.

‘Confound you, Ted Malone!’ said he. ‘That was a new ten-guinea machine.’

‘Can’t help it, Roy. I saw you take the snap, and there was only one thing to do.’

‘How the devil did you get mixed up with my outfit?’ I asked, with righteous indignation.

The rascal winked and grinned. ‘There are always and means,’ said he.

‘But don’t blame your foreman. He thought it was just a rag. I swapped clothes with his assistant, and in I came.’

‘And out you go,’ said Malone. ‘No use arguing, Roy. If Challenger were here he would set the dogs on you. I’ve been in a hole myself so I won’t be hard, but I am watch-dog here, and I can bite as well as bark. Come on! Out you march!’

So our enterprising visitor was marched by two grinning workmen out of the compound. So now the public will at last understand the genesis of that wonderful four-column article headed ‘Mad Dream of a Scientist’ with the subtitle. ‘A Bee-line to Australia,’ which appeared in The Adviser some days later and brought Challenger to the verge of apoplexy, and the editor of The Adviser to the most disagreeable and dangerous interview of his lifetime. The article was a highly coloured and exaggerated account of the adventure of Roy Perkins, ‘our experienced war correspondent’ and it contained such purple passages as ‘this hirsute bully of Enmore Gardens,’ ‘a compound guarded by barbed wire, plug-uglies, and bloodhounds,’ and finally, ‘I was dragged from the edge of the Anglo-Australian tunnel by two ruffians, the more savage being a jack-of-all trades whom I had previously known by sight as a hanger-on of the journalistic profession, while the other, a sinister figure in a strange tropical garb, was posing as an Artesian engineer, though his appearance was more reminiscent of Whitechapel.’ Having ticked us off in this way, the rascal had an elaborate description of rails at the pit mouth, and of a zigzag excavation by which funicular trains were to burrow into the earth.

The only practical inconvenience arising from the article was that it notably increased that line of loafers who sat upon the South Downs waiting for something to happen. The day came when it did happen and when they wished themselves elsewhere.

My foreman with his faked assistant had littered the place with all my apparatus, my bellbox, my crowsfoot, the V-drills, the rods, and the weight, but Malone insisted that we disregard all that and descend ourselves to the lowest level. To this end we entered the cage, which was of latticed steel, and in the company of the chief engineer we shot down into the bowels of the earth. There were a series of automatic lifts, each with its own operating station hollowed out in the side of the excavation. They operated with great speed, and the experience was more like a vertical railway journey than the deliberate fall which we associate with the British lift.

Since the cage was latticed and brightly illuminated, we had a clear view of the strata which we passed. I was conscious of each of them as we flashed past. There were the sallow lower chalk, the coffee-coloured Hastings beds, the lighter Ashburnham beds, the dark carboniferous clays, and then, gleaming in the electric light, band after band of jet-black, sparkling coal alternating with the rings of clay. Here and there brickwork had been inserted, but as a rule the shaft was self-supported, and one could but marvel at the immense labour and mechanical skill which it represented. Beneath the coal-beds I was conscious of jumbled strata of a concrete-like appearance, and then we shot down into the primitive granite, where the quartz crystals gleamed and twinkled as if the dark walls were sown with the dust of diamonds. Down we went and ever down — lower now than ever mortals had ever before penetrated. The archaic rocks varied wonderfully in colour, and I can never forget one broad belt of rose-coloured felspar, which shone with an unearthly beauty before our powerful lamps. Stage after stage, and lift after lift, the air getting ever closer and hotter until even the light tussore garments were intolerable and the sweat was pouring down into those rubber-soled slippers. At last, just as I was thinking that I could stand it no more, the last lift came to a stand and we stepped out upon a circular platform which had been cut in the rock. I noticed that Malone gave a curiously suspicious glance round at the walls as he did so. If I did not know him to be amongst the bravest of men, I should say that he was exceedingly nervous.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”