When the World Screamed (6)

By:

October 18, 2015

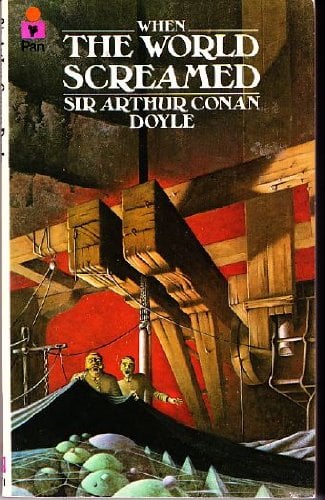

Arthur Conan Doyle’s novella When the World Screamed was first published in 1928. The fifth and final Professor Challenger adventure, it takes us not outward (e.g., to a South American plateau crawling with dinosaurs), nor inward (e.g., to an airtight chamber, while the Earth passes through a poison belt), but instead downward. Challenger, here described as “a primitive cave-man in a lounge suit,” while also “the greatest brain in Europe,” proposes to drill his way from a tract of land in Sussex (England) eight miles beneath the planet’s epidermis. Why? In order to prove his hypothesis that the world is itself a living organism! Enjoy.

‘Sorry, Roy, but you can’t get anything here. You’ll have to stay on that side of the wire. If you want more you must go and see Professor Challenger and get his leave.’

‘I’ve been,’ said the journalist, ruefully. ‘I went this morning.’

‘Well, what did he say?’

‘He said he would put me through the window.’

Malone laughed.

‘And what did you say?’

‘I said, “What’s wrong with the door?” and I skipped through it just to show there was nothing wrong with it. It was no time for argument. I just went. What with that bearded Assyrian bull in London, and this Thug down here, who has ruined my clean celluloid, you seem to be keeping queer company, Ted Malone.’

‘I can’t help you, Roy; I would if I could. They say in Fleet Street that you have never been beaten, but you are up against it this time. Get back to the office, and if you just wait a few days I’ll give you

the news as soon as the old man allows.’

‘No chance of getting in?’

‘Not an earthly.’

‘Money no object?’

‘You should know better than to say that.’

‘They tell me it’s a short cut to New Zealand.’

‘It will be a short cut to the hospital if you butt in here, Roy. Good-bye, now. We have some work to do of our own.

‘That’s Roy Perkins, the war correspondent,’ said Malone as we walked across the compound. ‘We’ve broken his record, for he is supposed to be undefeatable. It’s his fat, little innocent face that carries him through everything. We were on the same staff once. Now there’ — he pointed to a cluster of pleasant red-roofed bungalows — ‘are the quarters of the men. They are a splendid lot of picked workers who are paid far above ordinary rates. They have to be bachelors and teetotallers, and under oath of secrecy. I don’t think there has been any leakage up to now. That field is their football ground and the detached house is their library and recreation room. The old man is some organizer, I can assure you. This is Mr. Barforth, the head engineer-in-charge.’

A long, thin, melancholy man with deep lines of anxiety upon his face had appeared before us. ‘I expect you are the Artesian engineer,’ said he, in a gloomy voice. ‘I was told to expect you. I am glad you’ve come, for I don’t mind telling you that the responsibility of this thing is getting on my nerves. We work away, and I never know if it’s a gush of chalk water, or a seam of coal, or a squirt of petroleum, or maybe a touch of hell fire that is coming next. We’ve been spared the last up to now, but you may make the connection for all I know.’

‘Is it so hot down there?’

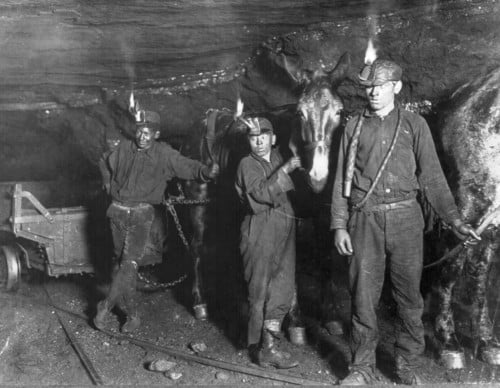

‘Well, it’s hot. There’s no denying it. And yet maybe it is not hotter than the barometric pressure and the confined space might account for. Of course, the ventilation is awful. We pump the air down, but two-hour shifts are the most the men can do–and they are willing lads too. The Professor was down yesterday, and he was very pleased with it all. You had best join us at lunch, and then you will see it for yourself.’

After a hurried and frugal meal we were introduced with loving assiduity upon the part of the manager to the contents of his engine-house, and to the miscellaneous scrapheap of disused implements with which the grass was littered. On one side was a huge dismantled Arrol hydraulic shovel, with which the first excavations had been rapidly made. Beside it was a great engine which worked a continuous steel rope on which the skips were fastened which drew up the debris by successive stages from the bottom of the shaft. In the power-house were several Escher Wyss turbines of great horse-power running at one hundred and forty revolutions a minute and governing hydraulic accumulators which evolved a pressure of fourteen hundred pounds per square inch, passing in three-inch pipes down the shaft and operating four rock drills with hollow cutters of the Brandt type. Abutting upon the engine-house was the electric house supplying power for a very large lighting instalment, and next to that again was an extra turbine of two hundred horse-power, which drove a ten-foot fan forcing air down a twelve-inch pipe to the bottom of the workings. All these wonders were shown with many technical explanations by their proud operator, who was well on his way to boring me stiff, as I may in turn have done my reader. There came a welcome interruption, however, when I heard the roar of wheels and rejoiced to see my Leyland three-tonner come rolling and heaving over the grass, heaped up with tools and sections of tubing, and bearing my foreman, Peters, and a very grimy assistant in front. The two of them set to work at once to unload my stuff and to carry it in. Leaving them at their work, the manager, with Malone and myself, approached the shaft.

It was a wondrous place, on a very much larger scale than I had imagined. The spoil banks, which represented the thousands of tons removed, had been built up into a great horseshoe around it, which now made a considerable hill. In the concavity of this horseshoe, composed of chalk, clay, coal, and granite, there rose up a bristle of iron pillars and wheels from which the pumps and the lifts were operated. They connected with the brick power building which filled up the gap in the horseshoe. Beyond it lay the open mouth of the shaft, a huge yawning pit, some thirty or forty feet in diameter, lined and topped with brick and cement. As I craned my neck over the side and gazed down into the dreadful abyss, which I had been assured was eight miles deep, my brain reeled at the thought of what it represented. The sunlight struck the mouth of it diagonally, and I could only see some hundreds of yards of dirty white chalk, bricked here and there where the surface had seemed unstable. Even as I looked, however, I saw, far, far down in the darkness, a tiny speck of light, the smallest possible dot, but clear and steady against the inky background.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”