Daniel Clowes — Against Groovy

By:

September 1, 2015

This essay originally appeared in The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition of Ghost World and Other Stories, with Essays, Interviews, and Annotations (Fantagraphics, 2013), edited by Ken Parille.

MORE CLOWES on HILOBROW: Josh Glenn’s 1999 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Josh Glenn’s 2002 Q&A with Daniel Clowes | Daniel Clowes as HiLo Hero.

Daniel Clowes is an avatar of a lost generation, the members of which were raised to regard themselves as Baby Boomers even though they came of age between the mid-1970s and the mid-1980s, thus missing out on the Sixties, the decade when actual Boomers came of age. So unwilling were they to be identified with their Boomer elders that two other avatars of Clowes’s 1954-1963 cohort — Douglas Coupland and Billy Idol — independently popularized a term expressing their contemporaries’ contempt for flawed generational periodization schemes: “Generation X.” Ironically, the same pop sociologists and lazy journalists who’d shoe-horned Clowes’s contemporaries into a demographics-driven Boomer generation (1943–1960 or 1946–1964) would later misapply the “Generation X” moniker to another, younger pseudo-generation. It’s confusing! So let’s call Clowes’s cohort “the Original Generation X.”

When I claim that Clowes (born in 1961) is an avatar of the 1954–1963 cohort, I don’t mean to suggest that the form or content of an artist’s or thinker’s work is inevitably shaped, in some neo-Marxist or quasi-astrological manner, by his or her generational worldview. At the same time, it’s undeniable that the 1884–1893 cohort produced Expressionism, Greenwich Village bohemianism, and The New Yorker; the 1904–1913 cohort produced Existentialism, Abstract Expressionism, and Big Band Swing; and the 1924–1933 cohort produced postmodernist fiction and theory, Neo-Dada, and Pop Art. I could go on. The point is, each generation’s distinctive output is always determined in critical ways by the social, economic, political, and cultural input with which its members grew up. I’ve dubbed Clowes an avatar of the Original Generation X because his work reflects and revolves around certain key inputs into OGXer consciousness: anti-Boomer ferocity, anti-hipsterism, apocalyptic fantasy, and trashy messianism. There are others, too, but we have to start somewhere.

Anti-Boomer Ferocity

Coming of age immediately after the Boomers did was like arriving at “a beach at the very end of a long summer of big crowds and wild goings-on,” write (Boomer) pop sociologists William Strauss and Neil Howe, who’ve been wrong about nearly everything except for this one point: “The beach bunch is sunburned, the sand shopworn, hot, and full of debris — no place for walking barefoot. You step on a bottle, and some cop cites you for littering.” Actually, they’re wrong about this stuff, too. True, it was no picnic growing up in the shadow of the Boomers; but OGXers (a generation Strauss and Howe don’t recognize) don’t envy the Boomers. Instead, OGXers are horrified and repulsed by the Boomers’ imaginative suggestibility — which is to say, their ability to immerse themselves whole-heartedly in some ethos or movement, only to drop it in favor of something else. To OGXers, the Boomers’ tendency to frame their lives in a mythical register is pathetic, their proneness to emotional excess is bogus; and their empathy is suspect.

To their immediate juniors, the Boomers’ serial absorption in, for example, the anti-war movement, drug experimentation, the women’s movement, the anti-nukes movement, environmentalism, and various self-actualization fads was a turn-off. In reaction to the Boomers’ example, OGXers have attempted — with greater and lesser degrees of success — to render themselves un-suggestible. At worst, this means that OGXers are a cynical bunch; at best, however, it means they’re serious (not earnest) and ironic, though in a philosophical way. Their immunity to suggestibility, acquired at an early age, came in handy during the Reagan era, when many of their elders and juniors allowed themselves to be persuaded by the dogma/myth that propositions considered extreme just a few years earlier — lowering taxes on the rich, shrinking the domestic safety net, prying the poor off welfare rolls — were actually good common sense.

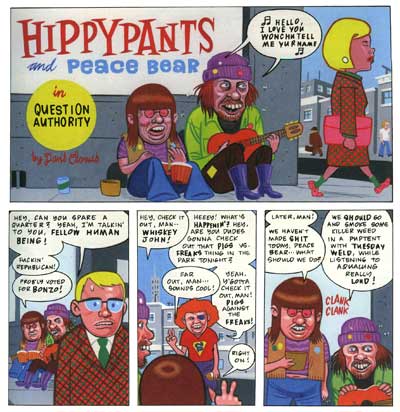

In a 1999 interview, Clowes told me that as a child, he didn’t like it when his Boomer older brother and “hippie” friends would smoke pot and walk around naked. Clowes remembers how much he’d hated it when, after a high-school classmate whom no one had liked died, “we had this thing where we all held hands and passed out strawberries… and we listened to Beatles songs.” And he’s frequently mentioned, in reference to his story “Art School Confidential” (1991) and the 2006 movie of that title, that he was disappointed by the Boomer ethos of his high-school art class and art-school teachers: “I would have much rather been held to [a slick commercial standard] than just be told everything is really nice and groovy.”

Asked in 1989 about the “underground comix” movement that preceded “alternative” comics, Clowes was dismissive. The so-called underground comix created by Boomers sold really well, he pointed out. “And here we are, in this generation, all of us fueled [only] by our own dedication. We have our own motives, no giant throng of mass culture behind us. I think what we are doing is commendable in its own way.” Clowes’s characters have no use for Boomers, either. In “I Love You Tenderly” (1990) Lloyd Llewellyn tells us that he hates hippie businessmen like Ben & Jerry, because they’re hypocrites who — like “underground” cartoonists who get rich — get to have it both ways.

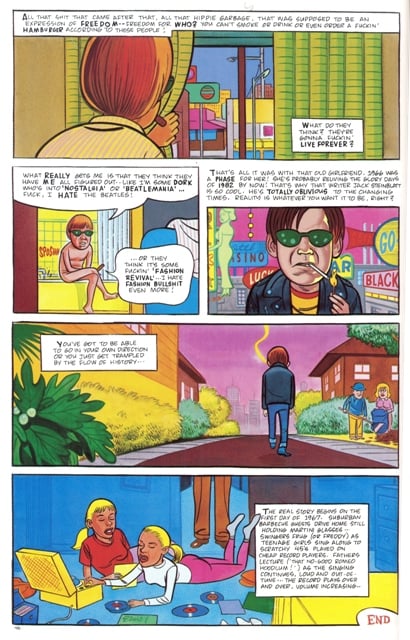

Since then, of course, alternative comics have become successful — and so has Clowes. It’s interesting to note that these days Clowes has largely abandoned the comic book for movies and graphic novels; perhaps he doesn’t want to be a hypocrite himself. “MCMLXVI” (1995), a story whose narrator rejects all cultural products produced after 1966 — i.e., during the Boomer heyday (“All that shit that came after [1966], all that hippie garbage, that was supposed to be an expression of freedom — freedom for who?”), asks whether it’s possible to be a non-hypocritical anti-Boomer without coming off as a monomaniacal, weird, holier-than-thou purist. Clowes seems worried and saddened that the answer is probably “no.”

In Modern Cartoonist, a 1997 manifesto for “alternative” comics (not his term), Clowes writes that since 1983 about twenty to twenty-five top-notch creators have created amazing comics. The movement, he claims, exists “in obscurity, free from the fear of state or corporate censorship and removed [unlike the so-called underground comix of the 1960s] from any cultural movements (its namelessness is an undeniable asset).” It’s this sort of perspective that makes Clowes an avatar of his nameless generation. Because “alternative” comics are (were) unsophisticated and culturally, financially insignificant, according to Clowes, the sophisticated and significant cartoonist can (could) do something amazing, something truthful and authentic that affects readers like no other art form.

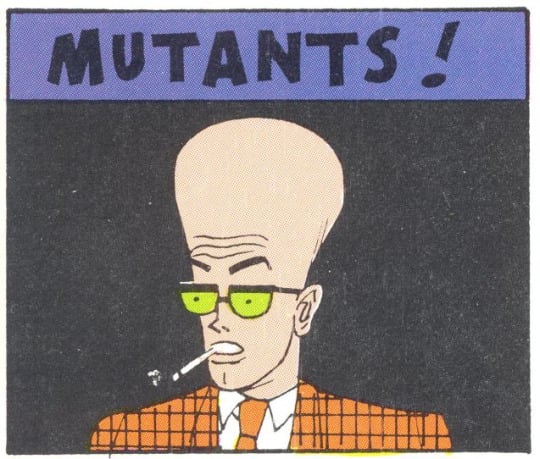

Anti-Hipsterism

Clowes’s generation gave us post-punk music, which — unlike the Boomers’ supposedly rebellious punk scene — was predicated on a rejection of hipness. OGxers — from John Lydon to “Weird Al” Yankovic — far prefer to be considered freakish than hip. It’s no surprise, then, to discover an anti-hipsterism theme running through Clowes’s work.

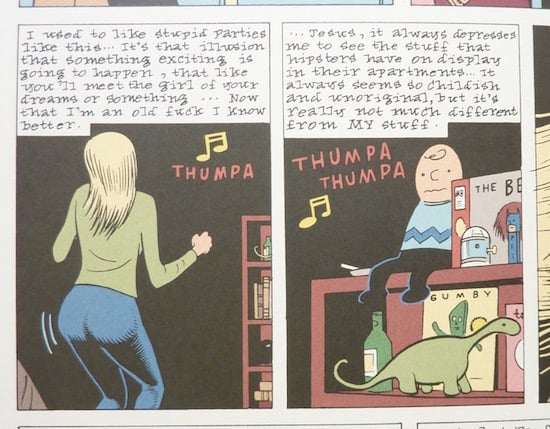

In the film version of Ghost World, the growing divide between Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer has everything to do with Rebecca’s slide into hipsterism. And in the first-person point of view story “The Party” (1993), the protagonist (apparently Clowes himself) stumbles into a party full of young hipsters who freak him out. “Jesus, it always depresses me to see the stuff that hipsters have on display in their apartments,” he laments. How is their “stuff” different from what OGXers (or Clowes stand-ins Enid Coleslaw and Rodger Young) might display in their apartments? Because the hipsters’ stuff — Charlie Brown doll, Batman Pez dispenser, Gumby and Dr. Who figurines, some kind of Beatles board game — is kitsch, there to be mocked by shallow ironists too young to associate any of it with their own childhoods. Worse than their shallow irony, though, is the hipsters’ desire to be “alternative fringe-dwelling types” (the OGXer ideal) and cool at the same time. Their have-it-both-ways-ism is all too Boomerish.

The story “Buddy Bradley in ‘Who Would You Rather Fuck: Ginger or Mary Ann?’” (1994) is Clowes’s most direct and savage attack on the OGXers’ immediate juniors, a cohort born from 1964–1973 (though Clowes describes them as having been born from 1966–76, which fits with his thesis that the Sixties began in ’66). Clowes has Peter Bagge’s character Stinky describe the culture of OGXers’ hipster juniors as one of “contrived contrariness.” Stinky continues: “We pose no threat to the standing order; we have directed out rebellion inward, seeking to provoke pity, disgust and regret in our parents rather than the fear of patricidal upheaval sought by previous ‘counter-cultures.’” Clowes has Bagge’s character Buddy, meanwhile, lament that from the Boomers his generation has taken underground media and “self-conscious sloppiness,” while from the OGXers they’ve taken “guiltless worship of junk”; his own generation is entirely unoriginal.

In these stories, Clowes was writing about my own generation, and I can’t fault him for seeing things how he saw them in the 1990s. When I look, now, at the generation currently in its 20s and 30s, I see a cohort dedicated to rebooting bygone cultural forms and franchises without nostalgia or irony. Even weirder, they seem to identify closely with their (Boomer) parents. Ugh! However: even as Eightball no. 13 was going to press, my generation was inventing the Web as we now know it — an upheaval more damaging to the status quo, for better or worse, than anything the Boomers or OGXers ever came up with. Generations grow up, and change, is my point. So let’s separate Clowes’s specific target (the 1964–1973 cohort) from his general target: the shallow irony, mocking pseduo-admiration for kitsch, and fake authenticity… of any generation.

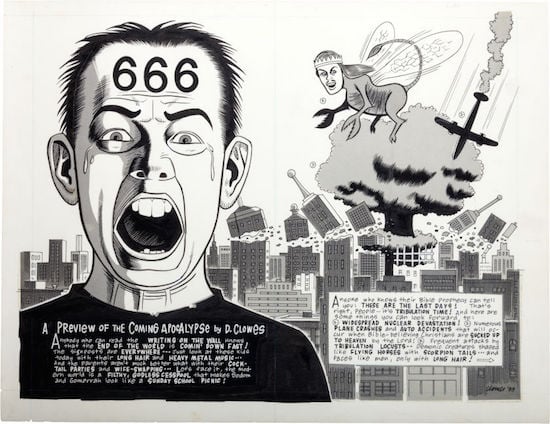

Apocalyptic Fantasy

OGXers were children and adolescents in 1964–1973, and adolescents and young adults in 1974-1983; in those days, nuclear disaster seemed a real possibility. In 1979, for example, Three Mile Island alerted us viscerally to the dangers of advanced technological civilization; and in 1983, 100 million of Americans watched the made-for-TV apocalyptic movie The Day After.

During that same period, young-adult literature was going through a craze for the “cozy catastrophe,” Brian Aldiss’s term for speculative fiction in which the end of civilization is experienced by its survivors as (in some respects) a change for the better. In John Christopher’s “Tripod” (1967–1968) and “Winchester” series (1971–1972), Peter Dickinson’s “Changes” series (1968–1970), O.T. Nelson’s libertarian The Girl Who Owned a City (1975), Robert O’Brien’s Z for Zachariah (1975), and Jack Kirby’s Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth comics (1972–1978), to name just a few of the most popular titles, post-apocalyptic scenarios make it possible for adolescent and teenage protagonists to experience unprecedented liberty, excitement, and opportunity for kicks. What adolescent or teenage reader wouldn’t respond positively to this sort of thing?

Clowes isn’t immune to the allure of the cozy catastrophe. In a 2001 interview about his quasi-apocalyptic 2000 graphic novel David Boring, Clowes says: “I always deep down think that something really terrible is just about to happen. I always have some vague awareness of some political event that I’m not quite up on that’s going to sweep into my life and change everything.” When the interviewer notes that, as a child, he’d wished for a nuclear catastrophe, Clowes replies, laughing, “Me too.” Earlier, in the semi-autobiographical story “Blue Italian Shit” (1994), Clowes has narrator/stand-in Rodger Young recount that he’d embraced the prospect of nuclear apocalypse in a punk (or post-punk) strategy of psychic survivalism in the face of life’s horrors.

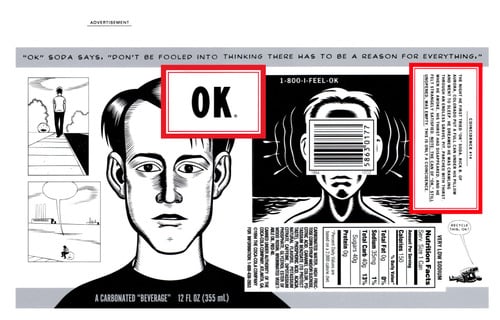

Not that we need to be too literal in our interpretation of how apocalyptic themes play out in the work of Clowes — and in the work of OGXers like, say, Alex Cox (director of Repo Man), Ivan Stang (Church of the SubGenius), and Adam Parfrey (Feral House). Jean Baudrillard’s 1981 book Simulacra and Simulations claimed that contemporary western culture was no longer dominated by (Enlightenment-style) disenchantment, production, and accumulation; in an important shift from his own earlier work, Baudrillard claimed the Enlightenment project had imploded into a black hole of nihilism and meaninglessness. OGXers, in other words, were living in a kind of epistemological or existential post-apocalyptic scenario; according to Baudrillard, the only form of survival or resistance possible within such a scenario requires embracing the (pre-Enlightenment) symbolic order, which is characterized by re-enchantment (vs. disenchantment), seduction (vs. production), and expenditure (vs. accumulation). Without suggesting that Clowes has ever read Baudrillard, I’d suggest that his early comics — the first Lloyd Llewellyn story appeared in 1985; Eightball began its run in 1989 — are characterized by re-enchantment, seduction, and expenditure. These comics privilege spontaneity and mystery over calculating reason; they cannot be interpreted, because they refer to no comprehensible reality (e.g., the nowhen context of the Lloyd Llewellyn stories); they celebrate waste and destruction. In fact, we might describe the “alternative” comics movement pioneered by Clowes and fellow OGXers — particularly Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, Charles Burns, and Kaz — this way.

Trashy Messianism

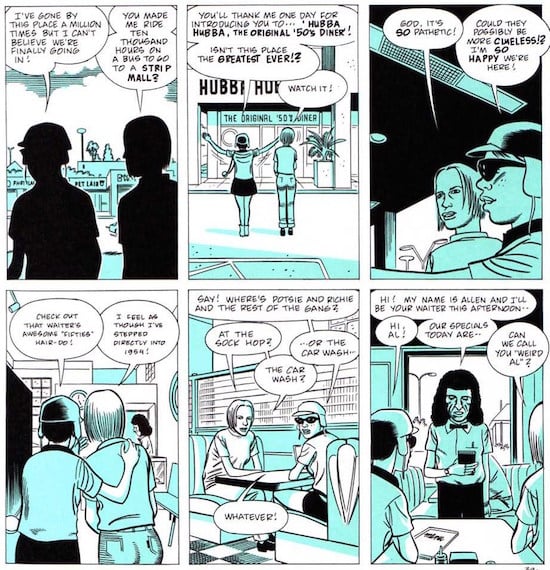

In “Blue Italian Shit,” Clowes’s narrator/stand-in Rodger Young at one point says that in 1979 New York City’s “unyielding filth carried with it a mystical, almost Biblical quality,” though he never explains what he means. We find a mystical-Biblical leitmotif in Ghost World (June 1993 – March 1997) whose meaning may be clearer. Enid Coleslaw, whose name is an anagram of the author’s, and who was based on young women from Clowes’s generation, keeps insisting that things like lousy comedians and diners with failed aesthetics are “God!” When I interviewed Clowes in 1999, I asked whether, for Enid, these things actually were God; he replied: “I think so. That’s somewhat literal. There’s some sort of spiritual component there.” This is the case, I’d argue, for every interesting OGXer.

OGXers like Clowes weren’t the first to find value in trash culture — Cubists and Dadaists, Neo-Dadaists and practitioners of Pop Art got there first. But unlike their elders, who appropriated trash in order to critique mainstream culture, OGXers don’t regard trash as kitsch. Or if they do, they’re still able to take trash culture seriously; perhaps they’re ironic when it comes to trash, but they’re not dismissively, self-protectively ironic. Speaking in 1989, for example, Clowes praised the dialogue from cult director Russ Meyer’s movies: “It all had its own style, sort of an overblown pretentiousness that was completely aware of the fact that it was overblown and pretentious but in such a slick, subtle way that it didn’t matter.” In the same interview, Clowes criticized the (Boomer-created) comics journal RAW — because it’s “an object that people like to own and show off, rather than a sleazy comic to hide behind the radiator.” In “I Love You Tenderly” (1990) Lloyd Llewellyn praises trash culture — he includes Eightball itself — because it’s not middlebrow, not “widely distributed, committee-manufactured, ‘marketable’ diluted gruel for the masses.” This is not to say that all pop culture is trash; Clowes and Lloyd Llewellyn agree that the opposite of middlebrow is “anything that represents a personal, singular vision, whether high art of obscene pornography.”

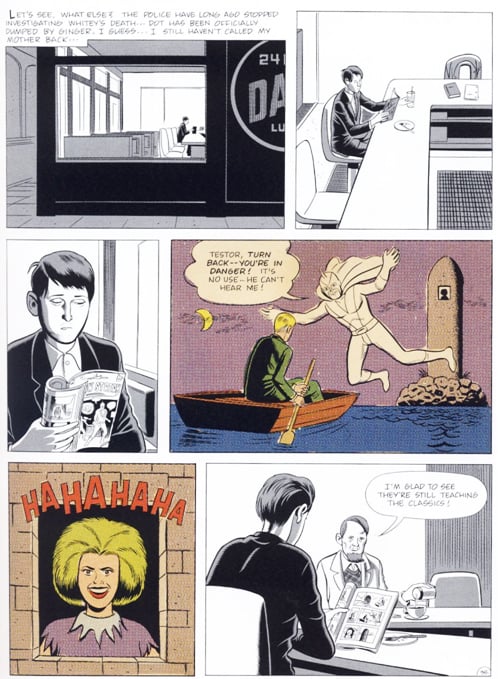

“The Young Manhood of Dan Pussey” (1990) and subsequent Dan Pussey stories are further studies in a generationally specific ambivalence towards trash. Though Clowes despises the stunted emotional intelligence of those who create and consume mindless superhero comics, he sides with Pussey against the Art Spiegelman-like editor of Emperor’s New Clothes, a highbrow comics magazine described as a “neoexpressodeconstructivist compendium of… kommmix.” Pussey is no high-lowbrow like Russ Meyer, but at least he’s not pretentious. With his stand-ins Enid Coleslaw, Lloyd Llewellyn (who proclaims his love for sexless wallflowers, honest-to-god eccentrics, and rejects), and Rodger Young (who says of lousy circus: “That’s real art, my friends… I wanted to cheer louder than anyone there, but I was afraid it would come out sounding insincere”), Clowes’s true sympathies are with those human, all-too-human types who fail to be successful, normal, and tasteful.

Like those OGXer hip-hop pioneers — including DJ Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa — who appropriated trashy disco samples in their music, and in so doing made those samples seem amazing, Clowes has long been devoted to his own medium’s trash: the cheap paper and disposable design of comics. In his first-ever interview, Clowes explains: “You see, comics are thought of as a sleazy art form and that’s something I’ve encouraged! Comics should be like Rock’n’Roll. They should have that sleazy quality, direct and iconoclastic, that gutter appeal. That’s not to say it can’t be great on every level, or that it can’t be high literature, but it can’t be pretentious or incomprehensible “art for art’s sake” nonsense.” Paraphrasing Philip K. Dick’s defense of trashy science fiction, comics are a medium for losers and misfits — who by definition aren’t hamstrung by bourgeois, middlebrow prejudices. It’s these prejudices, these blinders, that permit most of us from seeing God in everyday life: “One must work with the trash, pit it against itself,” Dick told Stanislaw Lem. “If God manifested Himself to us here He would do so in the form of a spraycan advertised on TV.”

“God” can mean all sorts of things; for Clowes, I’d suggest that God is a particular state of mind. In David Boring, that state of mind is evoked by brooding over fragments of pop culture — scraps of crappy superhero and little-kid comics books, to be precise. It’s as close as someone who firmly believes in the impossibility of narrative closure and existential unity can come to exaltation. Something similar is going on in Ghost World: Enid is dyed-in-the-wool ironist who avoids becoming cynical and jaded via her enthusiasm for trash culture. It’s God!