Pop with a Shotgun (4)

By:

July 3, 2015

[Between October 2005 and June 2009, HiLobrow contributor Devin McKinney worked with intermittent perseverance and passion to record his reactions to music and music-related stimuli at a blog called Pop with a Shotgun. He has selected some of his favorite posts for this reprint series. This installment, originally posted July 15, 2006, is the fourth of ten.]

*

Ain’t came yet

VARIOUS ARTISTS, Message to Love: The Isle of Wight Festival 1970

JIMI HENDRIX, Blue Wild Angel: Live at the Isle of Wight

JETHRO TULL, Nothing is Easy: Live at the Isle of Wight 1970

THE WHO, Live at the Isle of Wight Festival 1970

It’s not to be held against the Message to Love soundtrack that it is only the movie’s glorified echo, rather than a righteous, full-bodied experience in and of itself. Some of the music stands up (“Nights in White Satin”), some of it is decidedly less impressive when divorced from the image (the Doors’ bit). Just as your Eiffel Tower snow-dome is not Paris but a souvenir of Paris, this is not the movie but its tie-in. C’est la vie.

The individual releases suggest how good the music heard at the Isle of Wight that year was. Tull, who despite being uniformly dull on wax have never been bad in a movie (their “Song for Jeffrey” in the Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus bid fair to roast the Stones’ chestnuts, and they were the opening act), do a fantastic set. I’m not his fan-club president, but I do dig the spectacle and sound of Ian Anderson playing the suave-voiced goblin, his bathrobe flapping, his flute-stick waving, his scalp-fur flying. Whatever else Anderson is, he’s a rocker.

That Hendrix can be so blah and yet so brilliant beggars belief. I dunno about you but I ain’t came yet. There, I just came, thank you goodnight. The Who aren’t that offhand with their brilliance. They work at it, contributing a typically heroic two discs’ worth of mod classics stretched out and gouged up for the hippie set, plus forward-looking philosophizings on the order of “Naked Eye,” plus Tommy in its elephantine entirety. I can never boost the Who unequivocally because of my artistic “issues” with Townshend (Pete and I will have to get together and hash it all out someday), but damn if they didn’t sweat for their suburban mansions.

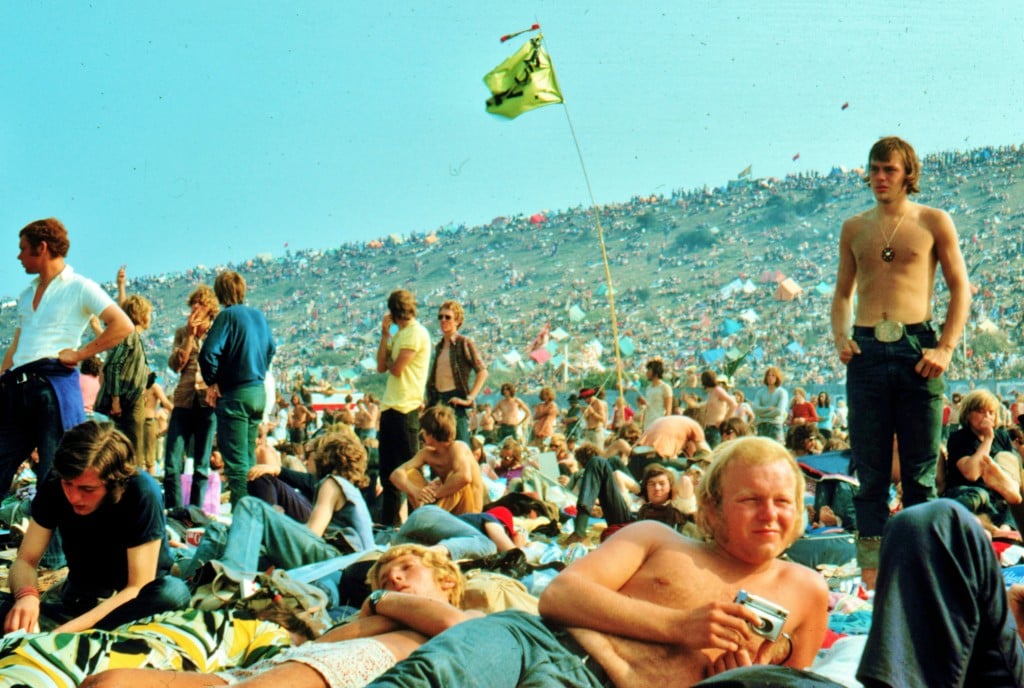

Now for all I know, the Murray Lerner documentary whose 1996 release — after many years of lapsed funds, false starts, and failed closures — spurred this glut of Wight-based dollar-makers was a stacked deck. Maybe the “last of the great rock festivals” wasn’t really that awful, that muddy and shitty down in the pit, that overrun with hateful hippies, mindless ideologues, foaming hounds, and self-consuming violence. (Then again, maybe it was: not only is Lerner’s evidence hard to gainsay, but the contemporary reporting in Rolling Stone pretty much bears it out.)

The point is not how true the film was or wasn’t. Ask any of the 600,000 who were there what the truth was and each will say different. The point is that Lerner, obviously a caring and scrupulous observer as well as an uncommonly sensitive documentarian and canny judge of music, imparted to the festival a grandeur, meaning, and depth it didn’t possess as it was happening but does now — now that time has passed and history is the forum. Message to Love is a great film, a prismatic horror house and emotional twister, with some of the greatest music you’ve ever heard from an almost unbelievable concatenation of artists. Among live rock films it fully deserves triple-billing with Gimme Shelter and Woodstock. But where the first of those was disgusting and the second dizzying, Message was saddening — as beatified and beautiful, elegant and elegiac as it sought to be.