Pop with a Shotgun (3)

By:

June 30, 2015

[Between October 2005 and June 2009, HiLobrow contributor Devin McKinney worked with intermittent perseverance and passion to record his reactions to music and music-related stimuli at a blog called Pop with a Shotgun. He has selected some of his favorite posts for this reprint series. This installment, originally posted October 16, 2005, is the third of ten.]

*

Excess and austerity

LEONARD COHEN, Death of a Ladies’ Man, Leonard Cohen at the Beeb

Regarding Cohen, I’m a one-album fan — that album being his first, Songs of Leonard Cohen, three of whose titles provided Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller with pretty much its entire soundtrack. It’s impossible to hear the album without seeing the movie in your head, impossible to imagine the movie without Cohen’s monotone mumbling behind the soundtrack’s upper registers of autumn rain and winter wind, filling in the notes and poetry Warren Beatty claims he’s got in his soul but lacks the tongue to utter.

Songs caught Cohen low and on the quiet, delicately treading the tightrope of his limitations. The tracks were long and balladic, dependent on repetition but deceptively melodic, and with only an exception or two they never grew boring. His voice — thin, humorless, narcotized — shouldn’t have worked, but it was the modest master of its transfixing half-octave. With these sketchy materials Cohen produced two standards, “Suzanne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” (the latter done definitively by Roberta Flack on her 1969 debut), the Altman-ready reveries, and a full rack of spellbinding narratives carried on ethereal production and women’s echoed voices.

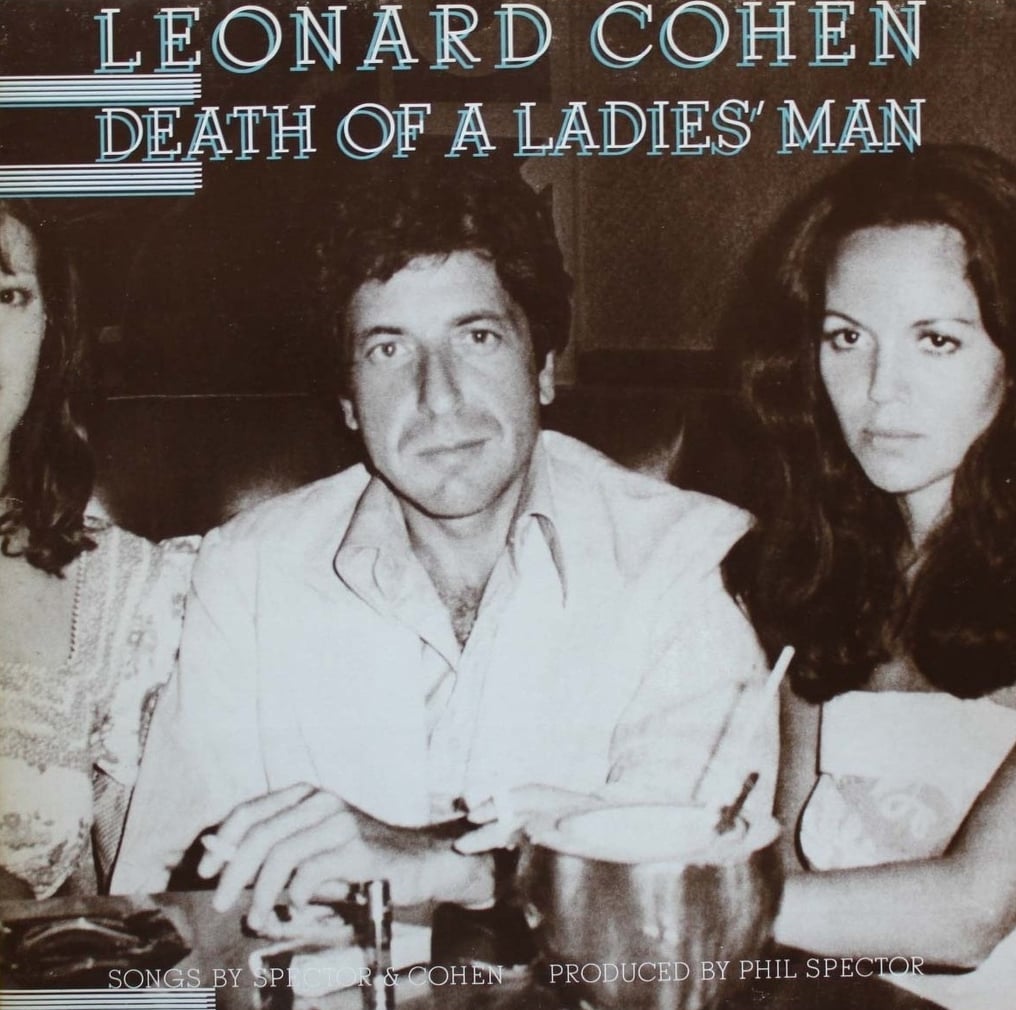

Death of a Ladies’ Man, a vague song cycle apparently about the male disease of big-dickism — I usually don’t listen to lyrics that closely — came out in 1977 and was produced by Phil Spector. That’s right, Phil Spector: chief architect of the Wall of Sound, returned from forests of obscurity, paranoia and gun-nuttery (into which he would, alas, one day disappear altogether) to lend Cohen’s low key a touch of the old Gotterdammerung. He replaced the finger-plucked delicacy of the first album with hammer-weight drums, stage-show horns, wild and braying choruses, a Radio City spectacular built around Cohen’s laconic lyrical miniatures.

It’s a grisly mismatch and of course it was intended that way. The production excess slathers irony like mortar and pushes emotion to realms of drunken promiscuity. Meanwhile Cohen’s voice is so affectless you can’t tell if he takes it seriously. But those are a pedant’s reservations. Death of a Ladies’ Man is queer and beautiful, and it’s your problem if you can’t wallow in it because you don’t feel certain of how the artists are feeling.

The lyrics come and go: some images are nice, others are lost in the funhouse. So what. Spector, baby of the Brill Building, clutches Cohen’s melodies and rides them on in. The songs become Fifties throwbacks or throat-hurling odes to beautiful losers, gross and gooey and embarrassingly over the top. Embarrassing mainly because there’s a layer of awareness and lack of the real desperation that carried, say, the Chantels’ great sides beyond embarrassment to states of pure emotionalism. But in place of desperation is a willingness to slop all over the place and make a big, big sound. Death of a Ladies’ Man is one of those things you’ve got to love, or puzzle over, in private. Play it in any but the perversest company and it’s a guaranteed room-emptier.

The Beeb thing boots a live BBC show c. 1970. Limpid and lovely, with a thin frosting of background organ and female chorus, and it ends just in time. Cohen offers concise, gnomic patter between songs.