Air Bridge (18)

By:

June 27, 2015

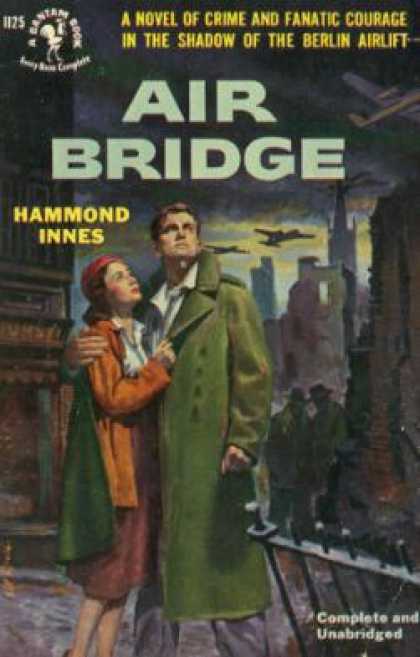

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

He stopped, staring at me. “What makes you think I did, Fraser?”

“Didn’t Diana send you?” I asked.

“Diana? No, of course not.”

“Why are you here then?”

“I might ask you the same question.” His gaze traveled quickly over the room, missing nothing and finally coming to rest on the Wehrmacht greatcoat I was wearing. “So this is where you’re hiding up. They told me at Gatow you’d disappeared from the sick bay.”

“You’ve been to the airport — today?”

He nodded. “I’ve just come from there.”

“Did you see Diana?”

“Yes. Why?”

“She knows the truth now, doesn’t she?” There was a puzzled frown on his face and I added quickly, “She knows Tubby is alive now. She knows that, doesn’t she?” My hands were sweating and I was almost trembling as I put the question.

“Alive? You know as well as I do he’s dead.” He was leaning slightly forward, and his gray eyes were no longer friendly. “So it’s true what they told me about you.”

“What did they tell you?”

“Oh, just that you were a sick man. That’s all.” He had thrown his hat on to the couch and he lowered his long body down beside it. “When will the Meyer girl be back? I guess I must just have missed her at the airport.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Did you see Pierce or the I.O.?”

“Yes, I saw them both.” He eyed me watchfully as though I was a strange dog that he was not quite sure of.

“I sent Pierce a report — a written report. Did he mention it?”

“No, he said nothing about a report.”

“Did he mention me at all?”

He lifted his eyes to my face. “Suppose you stop asking questions, Fraser?” His tone was abrupt, almost angry.

“But I must know,” I said. “I must know what he said about me.”

“All right — if you want to know — he said you were — ill.” He was watching me closely as he said this, like a doctor examining a patient for reaction.

I slumped down on to the farther end of the couch. “So he doesn’t believe it even when he sees it in writing.” I felt suddenly very weary. It would be so much easier just to say no more, give myself up and go back to England to stand trial. “I must get Tubby out,” I murmured. “I must get him out.” I was speaking to bolster my determination, but of course he stared at me as though I was mad. “You’re waiting to see Else, are you?” I asked, and when he gave an abrupt nod, I added, “Well, since you’ve nothing to do while you wait you may as well hear what happened that night in the Corridor. I’d like to know whether you believe me.”

“Why don’t you rest?” he suggested impatiently. “You look just about all in.”

“Can I have a cigarette? I’ve finished all mine.”

He tossed me a packet. “You can keep those.”

“Thanks.” I lit one. “Just because you’ve been told I’m ill, it doesn’t mean I can’t remember what happened. The chief thing for you to know is this: Tubby is alive. And but for that bastard Saeton he’d be here in Berlin now. It’s a pity your sister can’t recognize the truth when she hears it.”

I had his interest then and I went straight on to tell him the whole thing.

I was just finishing when footsteps sounded on the stairs outside — Else’s footsteps. She looked damnably tired as

she pushed open the door. “Fve done it, Neil. We —”

She stopped as she saw Culver. “I’m so sorry, Mr. Culyer. Have you been waiting long?”

“It hasn’t been long,” Culyer answered, rising to his feet. ‘Tve been talking to Fraser here — or rather, he’s been talking to me.”

Else glanced quickly from one to the other of us. “You know each other?”

“We met the other day — out at Gatow,” Culyer answered. “I tried to catch you at the airport, Miss Meyer, but I guess you’d just gone.” He glanced awkwardly at me. “Can we go somewhere and talk?” he asked her.

Else spread her hands in a quick gesture of despair. “I am afraid this is the only room I have. You will not mind, Neil, if we talk about our own business for a moment, will you?”

She turned to Culyer. “Have the British agreed? Shall I be permitted to go to Frankfurt?”

Culyer glanced hesitantly at me. Then he said, “Yes, everything’s fixed, Miss Meyer. As soon as your papers come through we’ll fly you down to Frankfurt and then you can join Professor Hinkmann of the Rauch Motoren and get to work right away. Of course,” he added, “you must realize Saeton is a jump or two ahead of us. His engines are flying right now.”

“Of course,” Else said. “What about patents?”

“That is still undecided,” Culyer answered. “We’re pressing hard for refusal of patent on the grounds that it’s largely your father’s work. Mind you, Saeton’s developed them to the flying stage, but I think our case may be strong enough for the whole thing to be left to sort itself out in open competition. Anyway, what I wanted to tell you was that the British have agreed for you to come to Frankfurt I thought you’d want to know that right away.”

“Thank you — yes.” She hesitated and then asked, “No questions about the papers I had in England?”

“No questions. They’ll forget about that.”

Else turned and pulled off her beret. She stood for a moment staring at the large photograph of her father that stood above the huge oak tallboy. “He would have been glad about this.” She suddenly swung round to Culyer again. “It was Saeton who informed the British security officials about my papers, wasn’t it?”

Culyer shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t think we need concern ourselves with that, Miss Meyer.”

“No, perhaps it is not important.” She turned to me. “Saeton has requested the permission of the station commander to fly a plane to Hollmind.”

“To Hollmind?” I stared at her, hardly able to believe my ears. “When?”

“Tonight.”

“Are you certain?” I asked urgently. “How do you know?”

She smiled. “I have friends at Gatow — a young officer of the R.A.S.C. tell me. Saeton is flying there tonight, just to make certain.”

For a second I was filled with relief. Saeton had realized he had been inhuman. He was going to get Tubby out. And then Else’s choice of words thrust themselves into my mind. Just to make certain. In an instant the monster I had built of Saeton was there again in my mind. “Just to make certain,” I heard myself say aloud. “My God! It can’t be that. It can’t be.”

“What’s that you say?” Culyer asked uneasily.

But I was looking at Else, wondering whether she knew what was in my mind. “It must be tonight,” I said.

“What must be tonight?” Culyer asked.

“Nothing,” Else said quickly. “Please, Mr. Culyer. I am very tired and I have some things to do.”

He looked uncertainly from one to the other of us and then picked up his hat. “Okay, Miss Meyer. I’ll be getting along then. As soon as the formalities are through I’ll contact you.”

“Thank you.” She held the door open for him.

He hesitated on the threshold and his gaze swung back to me. He was obviously puzzled.

Else touched his arm. “You will not say anything — about Mr. Fraser. Please.”

He shrugged his shoulders. “I guess it’s none of my business anyway.”

But it was his business. He was Diana’s brother. “Will you be seeing your sister again?” I asked him.

He nodded. “I’m going out to Gatow right now.”

“Will you give her a message? Will you tell her Tubby will be all right — that it’s true what I said in that report, every word of it?”

He glanced across at Else. “Do you know about this?”

Else nodded.

“And do you believe him? Do you believe Carter is still alive, the way he says he is?”

“Of course,” Else said.

Culyer shook his head slowly. “I don’t know what to think. But I’ll give her your message, Fraser. Maybe if Saeton’s flying out there —” He shrugged his shoulders.

“Good-night, Miss Meyer. I hope, we’ll have this thing all tied up very shortly now. This project has great possibilities and my headquarters…”

He was still talking as Else lighted him to the stairs, but I wasn’t listening. I was thinking of Tubby out there in that farmhouse. Saeton was flying to Hollmind. That was the thing that was still in my mind. I turned to the window. I had to get out there right away. I had to get there somehow. The door of the room closed and I swung round. Else was standing there, staring at me. “Are you all right, Neil?” she asked.

“Yes, of course I’m all right,” I answered irritably. “When you came in tonight — you started to say something?”

“Oh, yes. I have found a truck that is going into the Russian Zone. It is all fixed.”

“When for?” I asked. “It must be tonight. I must get there tonight.”

She nodded. “Yes. It is tonight.”

“Thank God!” I crossed the room and caught hold of her arms. “How did you manage it?” I asked.

“Oh, I find out about it from one of the drivers at Gatow. We have to be at the corner of Fassenenstrasse and the Kantstrasse at ten-thirty.”

“Not before?” I thought of the short time it would take to fly. “What time is Saeton leaving, do you know?”

She shook her head. “That is something I cannot find out. But he will not dare to go till it is very late if he have to leave the plane on Hollmind airfield.”

That was true. “How long will it take in this truck of yours?”

She shrugged her shoulders. “We do not go the direct way. There are things to be delivered, you understand. Two or three hours perhaps.”

Two or three hours! I turned away. “Couldn’t the driver be persuaded to go there first?”

“I do not think so,” she replied. “But I will talk to him. Perhaps if you have money —”

“You know I’ve no money,” I cut in. “A few marks —”

“Then we will see.”

I stopped in my pacing and turned to her. “We?” I asked. “You don’t mean you’re coming into the Russian Zone?”

“But of course.”

I started to dissuade her. But she was quite determined. “If I do not come the driver of the truck will not take you. It is a big risk for him. If we are stopped by the Red Army then there has to be some story that they can understand. It is better if you have a German girl with you.” She turned to the bed. “Now please, I must rest. You also. I do not think you are too well.”

Not too well! That phrase kept recurring to me as I lay sleepless on the couch.

Else was asleep the instant she had climbed into her bed. But I had been resting all day. There was no sleep left in me and all the time I lay there, feeling the cold even through my clothes and listening to the sound of the airlift planes overhead, I kept on turning her words over in my mind. Was she herself uncertain of my story? Was that why she was coming—to see whether it was the truth or only the hallucinations of a sick man? I remembered how Culyer had reacted.

I must have fallen asleep in, the end, for I woke in a sweat of fear that Tubby was dead and that the authorities at Gatow had been right in believing the Russian report.

And then I saw that Else was dressing and everything seemed suddenly normal and reasonable. We were going out of Berlin in a black market truck and in a few hours we should be coming back with Tubby. I was glad then that she was coming. If Tubby were dead, or if he didn’t survive the journey back, then she would be witness to the fact that he had been at the farmhouse at Hollmind, that he had been alive.

We had some food and by ten-thirty we were at the corner of the Fassenenstrasse and the Kantstrasse. The truck was late and it was very cold. By eleven o’clock I was becoming desperate, convinced that something had gone wrong with her arrangements and that it would not come. Else, however, seemed quite resigned to waiting. “It will come,” she kept saying. “You see. It will come.”

Three-quarters of an hour late it ground to a stop beside us, one of those ugly, long-nosed German vehicles driven by a youth who was introduced to me as Kurt and whose jaw bore the purple markings of a bad burn. An older man was with him in the cab. We bundled into the back, climbing over packing cases piled to the roof to a cramped and awkward space that had been left for us.

The gear cogs fought for a hold on each other, oil fumes seeped up from the floor, the packing cases jolted around us as we crawled out of Berlin.

We were nearly three hours in the back of that truck. We were cold and we both suffered from waves of nausea owing to the fumes. Periodically the truck stopped, packing cases were off-loaded and their place was taken by carcases of meat or sacks of flour. I cursed these delays, and at each stop it seemed more and more urgent that I should reach the farmhouse before Saeton.

At last all the packing cases had been off-loaded. We made one more stop, for poultry — there must have been hundreds of dead birds — and then at last through a rent in the canvas cover I saw that we had turned south. Shortly afterwards the truck stopped and I was told to get out and sit with the driver to direct him. We were then on the outskirts of Hollmind.

It was difficult to get my bearings after being cooped up in the body of the truck so long. However, I knew I had to get to the north of Hollmind and after taking several wrong turnings I at last found myself on a stretch of road that I remembered. By then the driver was getting impatient and he drove down it so fast that I nearly missed the track up to the farm and we had to back. The track was narrow and rutted and when he saw it the driver refused to take the truck up it. Else got down and did her best to persuade him, but he resolutely shook his head. “If I go there,” he told her, “I may get stuck. Also I do not know these people at the farm. The Red Army may be billeted there. Anything is possible. No. I wait for you here on the road. But hurry. I do not like to remain parked at the side of the road too long — it is very conspicuous.”

So Else and I went up the track alone, the ice crackling under our feet, the mud of the ruts black and hard like iron. “How far?” she asked.

“About half a mile,” I said. My teeth were chattering and there was an icy feeling down my spine.

The lane branched and I hesitated, trying to remember which track I had come down that night that seemed so long ago.

“You have been here before, haven’t you, Neil?” Else asked and there was a note of uncertainty in her voice.

“Of course,” I said and started up the left-hand fork. But it only led to a barn and we had to turn back and take the other fork. “We must hurry,” Else whispered urgently. “Kurt is a nervous boy. I do not wish for him to drive away and leave us.”

“Nor do I,” I said, thinking of the nightmare journey I had had into Berlin.

We were right this time and soon the shape of the farm buildings was looming up ahead of us against the stars.

“It’s all right,” I said as the silhouette of the outbuildings resolved itself into familiar lines. “This is the place.”

“So! The farm does exist. Your friend is alive.”

“Of course,” I said, “I told you —”

“I am sorry, Neil.” Her hand touched my arm.

“You mean you weren’t sure?”

“You were hurt and you look so ill. I do not know what to think. All I know is that it is urgent for you to come and that I must come with you.”

I could see the faint shape of her head. Her eyes looked very big in the darkness. I took hold of her hand. “Come on,” I said. “I hope to God —” I stopped then, for we had turned the corner of a barn and I saw there was a lamp on in the kitchen of the farmhouse. It was nearly two, yet the Kleffmanns hadn’t gone to bed. The shadow of a man crossed the drawn curtains. I hurried across the yard and tapped on the window.

It was Kleffmann himself who answered my tap. He came to the back door and peered nervously out into the night.

“Herr Kleffmann!” I called softly. “It’s me — Fraser. Can we come in?”

“Ja. Kommen Sie herein. Hurry please.” As he stood back to let us through the door he turned his face towards the lamplight that came through from the kitchen. He looked startled, almost scared.

“Is he all right?” I asked.

“Your friend? Yes, he is all right. A little better, I think.”

I breathed a sigh of relief. “We’ve got a truck waiting down on the road,” I said. “This is Fraulein Meyer.”

He shook hands with Else. “Come in. Come in, both of you.” He shut the door quickly and led us through into the kitchen. “Mutter. Here is Herr Fraser back again.”

Frau Kleffmann greeted me with a soft, eager smile, but her eyes strayed nervously to the stairs that led up from the kitchen. “I do not understand,” she murmured uneasily in German. Then she turned to her husband and said, “Why do they both come?”

I started to explain Else’s presence and then I stopped. That wasn’t what she had meant. Lying across the back of a chair was a heavy, fleece-lined flying jacket. Else had seen it, too. I turned to the Kleffmanns. They were standing quite still, staring towards the dark line of the stairs. From above us out of the silence of the house, came the sound of footsteps. They were coming down the stairs.

Else gripped my arm. “What is it?” she whispered.

I couldn’t answer her. My gaze was riveted to the stairs and all the muscles of my body seemed frozen in dread of the thing that was in my mind. The footsteps were heavy now on the bare boards of the landing. Then they were coming down the last flight. I saw the boots first and then the flying suit and followed the line of the zip to his face, “Saeton!” The name came from my lips in a whisper. God! I’ll never forget the sight of his face. It was gray like putty and his eyes burned in their sockets. He stopped at the sight of us and stood staring at me. Eyes and face were devoid of expression. He was like a man walking in his sleep.

“How’s Tubby?” My voice was hoarse and grating.

“He’s all right,” he answered, coming on down into the kitchen. “Why did you have to come here?” His voice was flat and lifeless and it carried with it a terrible note of sadness.

“I came to get him out,” I said.

He shook his head slowly. “It’s no use now.”

“What do you mean?” I cried. “You said he was all right. What have you done to him?”

“Nothing. Nothing that wasn’t necessary.”

I started towards the stairs then, but he stopped me. “Don’t go up,” he said. And then slowly he added, “He’s dead.”

“Dead?” The shock of the word drove me to action. I thrust past him, but he caught me by the arm as I started up the stairs. “It’s no good, Neil. He’s dead, I tell you.”

“But that is impossible!” Frau Kleffmann had retreated towards her chair by the fire. “Only this morning the doctor is here and he say he will be well again. Now you say he is dead.”

Saeton pushed his hand across his eyes. “It — it must have been a stroke — heart or something,” he muttered uncertainly.

“But only this evening he is laughing and joking with me,” Frau Kleffmann insisted. “Is not that so, Frederick?” she asked her husband. “Just before you come. I take him his food and he is laughing and saying I make him so fat he live up to his name.”

“Where is he?” Else whispered to me.

“Up at the top of the house. An attic. I’ll go up and see what’s happened.”

I started up the stairs again, but Saeton blocked my way. “He’s dead, I tell you. Dead. Going and looking at him won’t help.”

I stared at him. The blackness of the eyes, the smallness of the pupils — the man seemed curled up inside himself and through the windows of those eyes I looked in on fear and the bitter, driven urge of something that had stepped out of the world’s bounds. In sudden panic I flung him aside and leaped up the stairs. There was a small lamp on the landing and I picked it up as I turned to climb to the attic.

The door of Tubby’s room was ajar and as I went in the lamplight picked out the photographs of Hans lining the walls. My eyes swung to the bed in the corner and then I stopped. From the tumbled bedclothes Tubby stared at me with fixed and bloodshot eyes. His face had a bluish tinge even in the softness of the lamplight. There was a froth of blood on his puffed lips and his tongue had swollen so that it had forced itself between his teeth. He had struggled a great deal before he had died, for in the wreck of the bed his body lay in a twisted and unnatural attitude.

Avoiding the fixed gaze of his eyes, I crossed the room and touched the hand that had reached clear of the bed and was hanging to the floor. The flesh was still warm.

Else came into the room then and stopped. “So! It is true.” She looked across at me with a shudder. “How does it happen?”

“Perhaps it was a stroke. Perhaps —” My voice trailed away as I saw her eyes fasten on something that lay beside the bed.

“Look!” She shivered slightly, pointing to the pillow.

I bent and picked it up. It was damp and torn and bloody at the center where Tubby had fought for air. The truth of how he had died was there in my hands.

“He did it,” she whispered. “He killed him.”

I nodded slowly. I think I had known it all along. Tubby’s wasn’t the face of a man who had died a natural death. Poor devil! Alive he had threatened the future of Saeton’s engines. Because of that Saeton had come all the way from Berlin to kill him, to smother him as he lay helpless on the bed. The force that had been driving Saeton all along had taken him to the final and irrevocable step. He had killed the man without whom the engines could never have been made, the one man whom he’d thought of as a friend. If one man stood between me and success, I’d brush him aside. I could remember how he had stood in the center of the mess room at Membury and said that — and now he had done it. He had brushed Tubby aside. I dropped the pillow back on to the floor with a feeling of revulsion.

“I think he is mad.” Else’s horrified whisper voiced my own thoughts. And at that moment I heard slow, heavy footsteps on the stairs. Saeton was coming back up to the attic. I wasn’t prepared to face him yet. I reached for the door, closing it, my action unreasoned, automatic. I slid the bolt home and stood there, listening to the footsteps getting nearer.

“Come away from the door,” Else whispered urgently.

I stepped back and as I looked at her I saw she was scared.

The footsteps stopped outside the door and the handle turned. Then the thin deal boards bulged to the pressure of the man whose breathing I could hear. The room was very still as we waited. I think Else thought he would break the door down. I didn’t know what I expected, all I knew was that I didn’t want to talk to him. The silence in the room was heavy with suspense. Then his footsteps sounded on the stairs again as he went slowly down.

I opened the door and listened. There was the murmur of voices and then the side door closed with a bang. From the window I saw Saeton, looking big and squat in his flying jacket, cross the farmyard and go out through the gate by the barn. I felt relieved that he had left. It wasn’t only that I didn’t want to talk to him. I was scared of him. Perhaps Else’s fear was infectious, but I think it would have come, anyway. The abnormal in its most violent form is a thing all sane men are afraid of. The initiative lies with the insane. It’s that which is frightening.

I turned back to the door. “I’ll get Kleffmann,” I said. “We must get his body down to the truck and take it back to Berlin.” Tubby’s sightless eyes watched me in a fixed stare. I turned quickly and went down the stairs, conscious of Else’s footsteps hurrying after me.

The kitchen looked just the same as when we had entered it. Frau Kleffmann sat huddled in her thick dressing-gown by the fire. Her husband paced nervously up and down. There was nothing in the warmth and friendliness of that room to indicate what had happened upstairs in the attic — only the tenseness. Frau Kleffmann looked up quickly as I entered. “Is it true?” she asked. “Is he dead?”

“Yes,” I said. “He’s dead.”

“It is unbelievable,” she murmured. “And he was such a nice, friendly man.”

“Why did that other man — Herr Saeton — leave so quickly?” Kieffmann demanded.

I could see that he was suspicious, but there seemed no point in telling him what had happened. “He was worried about his plane,” I said. “Will you help me get Carter’s body down? We are taking it back to Berlin.”

“Ja.” He nodded. “Ja, I think that is best.”

“Would you please find something for us to carry him on?” I asked Frau Kleffmann.

She nodded, rising slowly to her feet, a little dazed by what had happened.

“You stay here, Else,” I said and followed Kleffmann up the stairs to the attic again. We covered Tubby with a blanket and got his body down the steep, narrow stairs. Back in the kitchen Else and Frau Kleffmann had fixed a blanket over two broom handles. The improvised stretcher lay on the table and we put Tubby’s body on it. Frau Kieffmann began weeping gently at the sight of his shrouded figure. I think she was remembering her son out there in a Soviet labor camp.

Else stood quite still, staring down at the shape huddled under the blanket.

“Will you help us to carry him down to the truck?” I asked Kleffmann.

“Ja. It is better that you take him away from here.” His voice trembled slightly and the sweat shone on his forehead. He had known as soon as he’d seen Tubby that the poor devil hadn’t died naturally and he wanted to get the body out of his house, to be shot of the whole business. He hadn’t said anything, but he knew who had done it and he was scared.

We picked the stretcher up, he at one end, I at the other. “Come on, Else,” I said.

She didn’t move and as I lifted the latch of the door she said, “Wait!” Her voice was pitched high on a hysterical note. “Do youthink Saeton will let you go back to Berlin with — with that.” She came across the room, seizing hold of my arm and shaking it in the extremity of her fear, “He cannot let either of us go back.”

I stood still, staring at her, the truth of what she Was saying gradually sinking in.

“He is waiting for us — out there.” She jerked her arm towards the window.

I could see in her eyes that she was still remembering the sight of Tubby’s face as he lay propped up in that bed. I lifted the stretcher back to the table and went towards the window. My hand was on the curtains to pull them back when Else seized my arm. “Keep away from the window. Please, Neil.” I could feel the trembling of her body.

I turned irresolutely back into the room. Was he really waiting for us out there? The palms of my hands were damp with sweat. Saeton had never turned back from anything he had started. He wouldn’t turn back now. Else and I were as fatal to him as a hangman’s rope. A desperate feeling of weariness took hold of me so that my limbs felt heavy and my movements were slow. “What do we do then?”

Nobody answered my question. They were all staring at me, waiting for me to make the first move. “Have you got a gun here?” I asked Kleffmann.

He nodded slowly. “Ja. I have a shotgun.”

“That will do,” I said. “Can I have it, please?” He went out of the room and returned a moment later with the gun. It looked about the equivalent of an English 16 bore. He gave it to me together with a handful of cartridges. “I’ll go out by a window on the other side of the house,” I said. “When I’ve gone, keep the doors bolted.” I turned to Else. “I’ll circle the house and then go down to the road and persuade Kurt to bring the truck up here.”

She nodded, her lips compressed into a tight line.

“If I find it’s all clear, I’ll whistle a bit of the Meistersingers. Don’t open up until you hear that.” I turned to Kleffmann. “Have you got another gun?”

He nodded. “I have one I use for the rooks.”

“Good. Keep it by you.” I broke the gun I held in my hands and slipped a cartridge into each of the barrels. I felt like a man going out to finish off an animal that has run amok.

As I snapped the breech Else, caught hold of my hand. “Be careful, Neil. Please. I — I do not. know what I shall do if I lose you now.”

I stared at her, surprised at the intensity of feeling in her voice. “I’ll be all right,” I said. And then I turned to Kleffmann and asked him to show me to the other side of the house.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”