Air Bridge (9)

By:

April 26, 2015

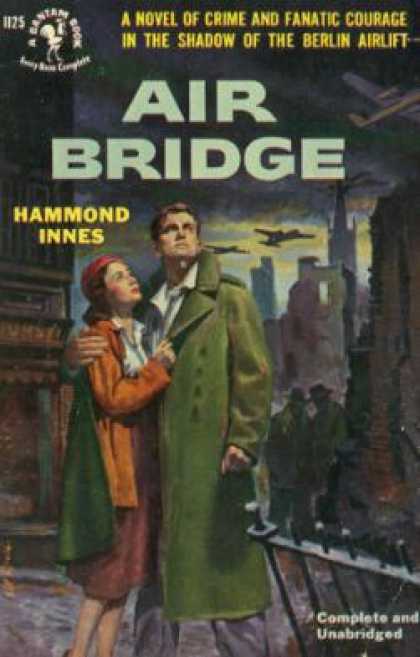

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Hammond Innes’s 1951 espionage thriller/Robinsonade Air Bridge. Set in England during the Berlin blockade and airlift of 1948–49 (during which time the British RAF and other aircrews frustrated the Soviet Union’s attempt to gain practical control of that city), the novel’s protagonist is a mercenary pilot… but is he a traitor? Hammond Innes wrote over 30 adventures, many of them set in hostile natural environments. Enjoy!

I won’t attempt to defend my decision. Saeton had asked me to steal a plane and I agreed to do it. I must take full responsibility, therefore, for all that happened afterwards as a result of that decision.

We went down to Ramsbury and in the smoky warmth of the pub that faces the old oak, he went over the plan in detail. I know it sounds incredible — to steal a plane off such a highly organized operation as the Berlin Airlift and then, after replacing, two of the engines, to fly it back to Germany and operate it from the same airfield from which it had been stolen. But he had it all worked out. And when he had gone over all the details, it didn’t seem incredible any more.

The devil of it was the man’s enthusiasm was infectious. I can see him now, talking softly in the hubbub of the bar, his eyes glittering with excitement, smoking cigarette after cigarette, his voice vibrant as he reached out into my mind to give me the sense of adventure that he felt himself. The essence of his personality was that he could make others believe what he believed. In any project, he gave himself to it so completely that it was impossible not to follow him. He was a born leader. From being an unwilling participant, I became a willing one. Out of apparent failure he conjured the hope of success, and he gave me something positive to work for. I think it was the daring of the plan that attracted me more than anything else. And, of course, I was up to the hilt in the thing financially. I may have thought it was money better thrown away considering how I’d got it, but no one likes to be broke when he is shown a way to make a fortune. The only thing he didn’t allow for was the human factor.

As we left the pub he said, “You’ll be seeing Tubby tomorrow. Don’t tell him anything about this. You understand? He’s not to know. His family were Methodists.” He grinned at me as though that explained everything that constituted Tubby Carter’s make-up.

Early the following morning Saeton drove me to Hungerford Station. Riding behind him on the old motor bike through the white of the frozen Kennet valley I felt a wild sense of exhilaration. For over five weeks I hadn’t been more than a few miles from Membury airdrome. Now I was going back into the world. Twenty-four hours ago I should have been scared at the prospect, afraid, that I might be picked up by the police. Now I didn’t think about it. I was bound for Germany, riding a mood of adventure that left no room in my mind for the routine activities of the law.

Tubby met me at Northolt. “Glad to see you, Neil,” he said, beaming all over his face, his hand gripping my arm. “Bit of luck Morgan going sick. Not that I wish the poor chap any harm, but it just happened right for you. Harcourt leaves for Wunstorf with one of the Tudors this evening. You’re flying a test with him this afternoon in our plane.”

I glanced at him quickly. “Our plane?”

He nodded, grinning. “That’s right. You’re skipper. I’m engineer. A youngster called Harry Westrop is radio operator and the navigator is a fellow named Field. Come on up. to the canteen and meet them. They’re all here.”

I could have wished that Tubby wasn’t to be a member of the crew. I immediately wanted to tell him the whole thing. Maybe it would have been better if I had. But I remembered what Saeton had said, and seeing Tubby’s honest, friendly features, I knew Saeton was right. It was out of the question. Duty, not adventure, was his business in life. But it was going to make it that bit more difficult when I ordered the crew to bail out.

I began to feel nervous then. It was a long time since I’d flown operationally, a long time since I’d skippered an air crew. We went into the bar, and Tubby introduced me to the rest of the crew. Westrop was tall and rather shy with fair, crinkly hair. He was little more than a kid. Field was much older, a small, sour-looking man with sharp eyes and a sharper nose. “What are you having, skipper?” Field asked. The word “skipper” brought back memories of almost-forgotten nights of bombing. I ordered a Scotch.

“Field is just out of the R.A.F.,” Tubby said. “He’s been flying the airlift since the early days at Wunstorf.”

“Why did you pack up your commission?” I asked him.

He shrugged his shoulders. “I got bored. Besides, there’s more money in civil flying.” He looked at me narrowly out of his small, unsmiling eyes. “I hear you were in 101 Squadron. Do you remember —” That started the rem iniscences. And then suddenly he said: “You got a gong for that escape of yours, didn’t you?”

I nodded.

He looked at the ceiling and pursed his thin lips. I could see the man’s mind thinking back. “I remember now. Longest tunnel escape of the war and then three weeks on

the run before —” He hesitated and then snapped his fingers. “Of course. You were the bloke that flew a Jerry plane out, weren’t you?”

“Yes,” I said. I was feeling suddenly tight inside. Any moment he’d ask me what I’d been doing since then.

“By jove! That’s wizard!” Westrop’s voice was boyish and eager. “What happened? How did you get the plane?”

“I’d rather not talk about it,” I said awkwardly.

“Oh, but dash it. I mean —”

“I tell you, I don’t want to talk about it.” Damn it! Suppose his parachute didn’t open? I didn’t want any hero-worship. I must keep apart from the crew until after the first night flight.

“I only thought —”

“Shut up!” My voice sounded harsh and violent.

“Here’s your drink,” Tubby said quietly, pushing the glass towards me. Then he turned to Westrop. “Better go and check over your radar equipment, Harry.”

“But I’ve just checked it.”

“Then check it again,” Tubby said in the same quiet voice. Westrop hesitated, glancing from Tubby to me. Then he turned away with a crestfallen look. “He’s only a kid,” Tubby said and picked up his drink. “Well, here’s to the airlift!” Here’s to the airlift! I wondered whether he remembered the four of us drinking that toast in the mess room at Membury. It all seemed a long time ago. I turned to Field. “What planes were you navigating on the lift?” I asked him.

“Yorks,” he replied. “Wunstorf to Gatow with food for the bloody Jerry.” He knocked back his drink. “Queer, isn’t it? Just over three years ago I was navigating bombers to Berlin loaded with five hundred pounders. Now, for the last four months I’ve been delivering flour to them — flour that’s paid for by Britain and America. Do you think they’d have done that for us?” He gave a bitter laugh. “Well, here’s to the Ruskies, God rot ’em! But for them we could have been a lot tougher.”

“You don’t like the Germans?” I asked, glad of the change in conversation.

He gave me a thin-lipped smile. “You should know about them. You’ve been inside one of their camps. They give me the creeps. They’re a grim, humorless lot of bastards. As for Democracy, they think it’s the biggest joke since Hitler wiped out Lidice. Ever read Milton’s Paradise Lost? Well, that’s Germany. Don’t let’s talk about it. Do you know Wunstorf?”

“I bombed it once in the early days,” I said.

“It’s changed a bit since then. So has Gatow. We’ve enlarged them a bit. I think you’ll be quite impressed. And the run in to Gatow is like nothing you’ve ever done before. You just go in like a bus service, and you keep rolling after touchdown because you know damn well there’s either another kite coming down or taking off right on your tail. But they’ll give you a full briefing at Wunstorf. It’s reduced to a system so that it’s almost automatic. Trouble is it’s bloody boring — two flights a day, eight hours of duty, whatever the weather. I tried for B.O.A.C., but they didn’t want any navigators. So here I am, back on the airlift, blast it!” His gaze swung to the entrance. “Ah, here’s the governor,” he said.

Harcourt was one of those men born for organization, not leadership. He was very short with a small, neat mustache and sandy hair. He had tight, rather orderly features and a clipped manner of speech that finished sentences abruptly like an adding machine. His method of approach was impersonal — a few short questions, punctuated by sharp little nods, and then silence while shrewd gray eyes stared at me unblinkingly. Lunch was an awkward affair carried chiefly by Tubby. Harcourt had an aura of quiet efficiency about him, but it wasn’t friendly efficiency. He was the sort of man who knows precisely what he wants and uses his fellow creatures much aS a carpenter uses his tools. It made it a lot easier from my point of view.

Nevertheless, I found the test flight something of an ordeal. It was the machine that was supposed to be on test. He’d only just taken delivery. But I knew as we walked out to the plane that it was really I who was being tested. He sat in the second pilot’s seat and I was conscious all through the take-off of his cold gaze fixed on my face and not on the instrument panel.

Once in the air, however, my confidence returned. She handled very easily and the fact that she was so like the one we’d flown only a few days before made it easier. Apparently I satisfied him, for as we walked across the airfield to the B.E.A. offices, he said, “Get all the details cleared up, Fraser, and leave tomorrow lunchtime. That’ll give you a daylight flight. I’ll see you in Wunstorf.”

We left Northolt the following day in cold, brittle sunshine that turned to cloud as we crossed the North Sea. Field was right about Wunstorf. It had changed a lot since I’d been briefed for that raid nearly eight years ago. I came out of the cloud at about a thousand feet and there it was straight ahead of me through the windshield, an enormous flat field with a broad runway like an autobahn running across it and a huge tarmac apron littered with Yorks. There were excavations marking new work in progress and a railway line had been pushed out right to the edge of the field. Beyond it stretched the Westphalian plain, grim and desolate, with a line of fir-clad hills marching back along the horizon.

I came in to land through a thick downpour of rain. The runway was a cold, shining ribbon of gray, half-obscured by a haze of driven rain. I went in steeply, pulled back the stick and touched down like silk. I was glad about that landing. Somehow it seemed an omen. I kicked the rudder and swung on to the perimeter track, the rain beating up from the concrete and sweeping across the field so that the litter of planes became no more than a vague shadow in the murk.

“Dear old Wunstorf!” Field’s voice crackled over the inter-com. “What a dump! It was raining when I left. Probably been raining ever since.”

A truck came out to meet us. We dumped our kit in it and it drove us to the airport buildings. They were a drab olive green; bleak utilitarian blocks of concrete. The Operations Room was on the ground floor. I reported to the squadron leader in charge. “If you care to go up to the mess they’ll fix you up.” Then he saw Field. “Good God! You back already, Bob?”

“A fortnight’s leave, that’s all I got out of getting demobilized,” Field answered.

“And a rise in pay I’ll bet.” The squadron leader turned to me. “He’ll get things sorted out for you. Report here in the morning and well let you know what your timings are.”

The station commander came in as he finished speaking, a big blond Alsatian at his heels. “Any news of that Skymaster yet?” he asked.

“Not yet, sir,” replied the squadron leader. “Celle have just been on again. They’re getting worried. It’s twenty minutes overdue. There’s been a hell of a storm over the Russian Zone.”

“What about the other bases?”

“Lubeck, Fuhlsbuttel, Fassberg — they’ve all made negative reports, sir. It looks as though it’s force-landed somewhere. Berlin are in touch with the Russians, but so far Safety Center hasn’t reported anything.”

“Next wave goes out at seventeen hundred, doesn’t it? If the plane hasn’t been located by then have all pilots briefed to keep a lookout for it, will you?” He turned to go and then stopped as he saw us. “Back in civvies, eh, Field? I must say it doesn’t make you look any smarter.” He smiled and then his eyes met mine. “You must be Fraser.” He held out his hand to me. “Glad to have you with us. Harcourt’s up at the mess now. He’s expecting you.” He turned to the squadron leader. “Give the mess a ring and tell Wing-Commander Harcourt that his other Tudor has arrived.”

“Very good, sir.”

“We’ll have a drink sometime, Fraser.” The station commander nodded and hurried out with his dog.

“I’ll get you a car,” the squadron leader said. He went out and his shout of “Fahrer!” echoed in the stone corridor.

The mess was a huge building; block on block of gray concrete, large enough to house a division. When I gave my name to the German at the desk he ran his finger down a long list. “Block C, sir — rooms 231 and 235. Just place your baggage there, please. I will arrange for it. And come this way, gentlemen. Wing-Commander Harcourt is wishing to speak with you.” So Harcourt retained his Air Force title out here! We followed the clerk into the lounge. It had a dreary waiting-room atmosphere. Harcourt came straight over. “Good trip?” he asked.

“Pretty fair,” I said.

“What’s visibility now?”

“Ceiling’s about a thousand,” I told him. “We ran into it over the Dutch coast.”

He nodded. “Well, now we’ve got six planes here.” Hiere was a touch of pride in the way he said it and this was reflected in the momentary gleam in his pale eyes. He’d every reason to be proud. There was only one other company doing this sort of work. How he’d managed to finance it, I don’t know. He’d only started on the airlift three months ago. He’d had one plane then. Now he had six. It was something of an achievement and I remember thinking, This man is doing what Saeton is so desperately wanting to do. I tried to compare their personalities. But there was no point of similarity between the two men. Harcourt was quiet, efficient, withdrawn inside himself. Saeton was ruthless, genial — an extrovert and a gambler.

“Fraser!”

Harcourt’s voice jerked me out of my thought, “Yes?”

“I asked you whether you’re okay to start on the wave scheduled for 10:00 hours tomorrow?”

He nodded. “Good. We’ve only two relief crews at the moment so you’ll be worked pretty hard. But I expect you can stand it for a day or two.” His eyes crinkled at the corners. “Overtime rates are provided for in your contracts.” He glanced at his watch. “Time I was moving. There’s a wave due to leave at seventeen hundred. Field knows his way around.”

He left us then and we went in search of our rooms. It was a queer place, the Wunstorf Mess. You couldn’t really call it a mess — aircrews’ quarters would be a more apt description. It reminded me of an enormous jail. Long concrete corridors echoed to ribald laughter and the splash of water from communal washrooms. The rooms were like cells, small dormitories with two or three beds. One room we went into by mistake was in darkness with the blackout blinds drawn. The occupants were asleep and they cursed us as we switched on the light. Through the open doors of other rooms we saw men playing cards, reading, talking, going to bed, getting up. All the life of Wunstorf was here, in these electrically-lit, echoing corridors. In the washrooms men in uniform were washing next to men in pajamas quietly shaving as though it were early morning. These billets brought home to me more than anything the fact that the airlift was a military operation, a round-the-clock service running on into infinity.

We found our rooms. There were two beds in each. Carter and I took one room; Westrop and Field the other. Field wandered in and gave us a drink from a flask. “It’s going to be pretty tough operating six planes with only two relief crews,” he said. “It means damn nearly twelve hours duty a day.”

“Suits me,” I replied.

Carter straightened up from the case he was unpacking. “Glad to be back in the flying business, eh?” He smiled.

I nodded.

“It won’t last long,” Field said.

“What won’t?” I asked.

“Your enthusiasm. This isn’t like it was in wartime.” He dived across the corridor to his room and returned with a folder. “Take a look at this.” He held a sheet out to me. It was divided into squares — each square a month and each month black with little ticks. “Every one of these ticks represents a trip to Berlin and back, around two hours’ flying. It goes on and on, the same routine. Wet or fine, thick mist or blowing half a gale, they send you up regular as clockwork. No let-up at all. Gets you down in the end.” He shrugged his shoulders and tucked the folder under his arm. “Oh, well, got to earn a living, I suppose. But it’s a bloody grind, believe you me.”

After tea I walked down to the airfield. I wanted to -be alone. The rain had stopped, but the wind still lashed at the pine trees. The loading apron was almost empty, a huge, desolate stretch of tarmac shining wet and black in the gray light. Only planes undergoing repairs and maintenance were left, their wings quivering soundlessly under the stress of the weather. It was as though all the rest had been spirited away. The runways were deserted. The place looked almost as empty as Membury.

I turned back through the pines and struck away to the left, to the railway sidings that had been built out to the very edge of the landing field. A long line of fuel wagons was being shunted in, fuel that we should carry to Berlin. The place was bleak and desolate. The country beyond rolled away into the distance, an endless vista of agriculture, without hedges or trees. Something of the character of the people seemed inherent in that landscape— inevitable, ruthless and without surprise. I turned, and across the railway sidings I caught a glimpse of the wings of a four-engined freighter — symbol of the British occupation of Germany. It seemed suddenly insignificant against the immensity of that rolling plain.

We were briefed by the officer in charge of Operations at nine o’clock the following morning. By ten we were out on the perimeter track waiting in a long queue of planes, waiting our turn with engines switched off to save petrol. Harcourt had been very insistent about that. “It’s all right for the R.A.F.,” he had said. “The taxpayer foots their petrol bill. We’re under charter at so much per flight. Fly on two engines whenever possible. Cut your engines out when waiting for take-off.” It made me realize how much Saeton had to gain by the extra thrust of those two engines and their lower fuel consumption.

The thought of Saeton reminded me of the thing I’d promised to do. I wished it could have been this first flight I wanted to get it over. But it had to be a night flight. I glanced at Tubby. He was sitting in the second pilot’s seat, the earphones of his flying helmet making his face seem broader, his eyes fixed on the instrument panel. If only I could have had a different engineer. It wasn’t going to be easy to convince him.

The last plane ahead of us swung into position, engines revving. As it roared off up the runway the voice of Control crackled in my earphones. “Okay, Two-five-two. You’re clear to line up now. Take off right away.” Perhaps it was as well to fly in the daylight first, I thought, as I taxied to the runway end and swung the machine into position.

We took off dead on time at 10:18. For almost three-quarters of an hour we flew north-east making for the entry to the northern approach corridor for Berlin. “Corridor beacon coming up now,” Field told me over the inter-com. “Turn on to 100 degrees. Time 11:01. We’re minus thirty seconds.” That meant we were thirty seconds behind schedule. The whole thing was worked on split-second timing. Landing margin was only ninety seconds either side of touch-down timing. If you didn’t make it inside the margin you just had to overshoot and return to base. The schedule was fixed by timings over radar beacons at the start and finish of the air corridor that spanned the Russian Zone. Fixed heights ensured that there were no accidents in the air. We were flying Angels three-five — height 3,500 feet. Twenty miles from Frohnau beacon Westrop reported to Gatow Airway.

As we approached Berlin I began to have a sense of excitement. I hadn’t been over Berlin since 1945. I’d been on night raids then. I wondered what it would look like in daylight. Tubby seemed to feel it, too. He kept on looking down through his side window and moving restlessly in his seat. I pushed my helmet back and shouted to him. “Have you seen Berlin from the air since the war?”

He nodded, abstractedly. “I was on transport work.”

“Then what are you so excited about?” I asked.

He hesitated. Then he smiled — it was an eager, boyish smile. “Diana’s at Gatow. She’s working in the Malcolm Club there. She doesn’t know I’m on the airlift.” He grinned. “I’m going to surprise her.”

Westrop’s voice sounded in my earphones, reporting to Gatow Airway that we were over Frohnau beacon. We switched to contact with Traffic Control, Gatow. “Okay, Two-five-two. Report again at Lancaster House.” So Diana was at Gatow. It suddenly made the place seem friendly, almost ordinary. It would be nice to see Diana again. And then I was looking out of my side window at a bomb-pocked countryside that merged into miles of roofless, shattered buildings. There were great flat gaps in the city, but mostly the streets were still visible, bordered by the empty shells of buildings. From the air it seemed as though hardly a house had a roof. We were passing over the area that the Russians had fought through. Nothing seemed to have been done about it. It might have happened yesterday instead of four years ago.

Over the center of the city Field gave me my new course and Westrop reported to Gatow Tower, who answered, “Okay, Two-five-two. Report at two miles. You’re Number Three in the pattern.”

There was less damage here. I caught a glimpse of the Olympic stadium and then the pine trees of the Grunewald district were coming up to meet me as I descended steeply. Havel Lake opened out, the flat sheet of water across which the last survivors from the Fuehrer Bunker had tried to escape, and Westrop reported again. “Clear to land. Two-five-two,” come the voice of Gatow Control. “Keep rolling after touchdown. There’s a York close behind you.”

I lowered undercarriage and landing flaps. We skimmed the trees and then we were over a cleared strip of woods dotted with the posts of the night landing beacons with the whole circle of Gatow Airport opening up and the pierced steel runway rising to meet us. I leveled out at the edge of the field. The wheels bumped once, then we were on the ground, the machine jolting over the runway sections. I kept rolling to the runway end, braked and swung left to the off-loading platform.

Gatow was a disappointment after Wunstorf. It seemed much smaller and much less active. There were only five aircraft on the apron. Yet this field handled more traffic than either Tempelhof in the American Sector or Tegel in the French. As I taxied across the apron I saw the York behind me land and two Army lorries manned by a German labor team, still in their field gray, nosed out to meet it. I went on, past the line of Nissen huts that bordered the apron, towards the hangars. Two Tudor tankers were already at Piccadilly Circus, the circular standing for fuel off-loading. I swung into position by a vacant pipe. By the time we had switched off and got out of our seats die fuselage door was open and a British soldier was connecting a pipeline to our fuel tanks.

“Where’s the Malcolm Club?” Tubby asked Field. His voice trembled slightly.

“It’s one of those Nissen huts over there,” Field answered, pointing to the off-loading apron. He turned to me. “Know what the Army call this?” He waved his hands towards the circular standing. “Remember they called the cross-Channel pipeline PLUTO? Well, this one’s called PLUME — Pipeline-under-mother-earth. Not bad, eh? It runs the fuel down to Havel where it’s shipped into Berlin by barge. Saves fuel on transport.”

We were crossing the edge of the apron now, walking along the line of Nissen huts. The first two were full of Germans. “Jerry labor organization,” Field explained.

“What about the tower?” I asked. Above the third Nissen hut was a high scaffolding with a lookout. It was like a workman’s hut on stilts.

“That’s the conrol tower for the off-loading platform. All this is run by the Army — it’s what they call a FASO. Forward Airfield Supply Organization. Here’s the Malcolm Club.” A blue board with R.A.F. roundel faced us. “Better hurry if you want some coffee.”

Tubby hesitated. “She may not be on duty,” he murmured.

“We’ll soon see,” I said and took his arm.

Inside the hut the air was warm and smelled of fresh-made cakes. A fire glowed red in an Army-type stove. The place was full of smoke and the sound of voices. There were about four aircrews there, in a huddle by the counter. I saw Diana immediately. She was in the middle of the group, her hand on the arm of an American Control officer, laughing happily, her face turned up to his.

I felt Tubby check and was reminded suddenly of that night at Membury when he and I had stood outside the window of our mess. Then Diana turned and saw us. Her eyes lit up and she rushed over, seizing hold of Tubby, hugging him. Then she turned to me and kissed me, too. “Harry! Harry!” She was calling excitedly across the room. “Here’s Tubby just flown in.” She swung back to her husband. “Darling — remember I told you my brother Harry was in Berlin. Well, here he is.”

I saw the stiffness leave Tubby’s face. He was suddenly grinning happily, shaking the big American’s hand up and down, saying, “My God! Harry. I should have recognized you from your photograph. Instead, I thought you were some boyfriend of Diana’s.” He didn’t even bother to hide his relief, and Diana never seemed to notice that anything had been wrong. She was taken too much by surprise. “Why didn’t you tell me you were flying in?” she cried. “You devil, you. Come on. Let’s get you some coffee. They only give you a few minutes here.”

I stood and watched her hustling him to the bun counter, wondering whether he had told her what had happened at Membury, wondering what she’d say if she knew I was going to ditch him in the Russian Zone.

“You must be Fraser.” Her brother was at my elbow. I’ve heard a lot about you from Di. My name’s Harry Culyer, by the way.” He had Diana’s eyes, but that was all they had in commonr He had none of her restlessness. He was the sort of man you trust on sight; big, slow-spoken, friendly. “Yes, IVe heard a lot about you and a crazy devil called Saeton. Is that really his name?” He gave a fat chuckle. “Seems apt from what Di told me.”

I wondered how much she had told him. “Are you connected with the airlift?” I asked him.

He shook his head. “No, I’m attached to the Control Office of the U.S. Military Government. I used to work for the Opel outfit before the war so they figured I’d have to stay on in some sort of uniform and keep an eye on vehicle production in the Zone. Right now I guess you could do with some coffee, eh?”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”