Jurgen (4)

By:

April 6, 2015

James Branch Cabell’s 1919 ironic fantasy novel Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice, the protagonist of which seduces women everywhere he travels — including into Arthurian legend and Hell itself — is (according to Aleister Crowley) one of the “epoch-making masterpieces of philosophy.” Cabell’s sardonic inversion of romantic fantasy was postmodernist avant la lettre. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Jurgen here at HILOBROW. Enjoy!

Thus it was that Jurgen and the Centaur came to the garden between dawn and sunrise, entering this place in a fashion which it is not convenient to record. But as they passed over the bridge three fled before them, screaming. And when the life had been trampled out of the small furry bodies which these three had misused, there was none to oppose the Centaur’s entry into the garden between dawn and sunrise.

This was a wonderful garden: yet nothing therein was strange. Instead, it seemed that everything hereabouts was heart-breakingly familiar and very dear to Jurgen. For he had come to a broad lawn which slanted northward to a well-remembered brook: and multitudinous maples and locust-trees stood here and there, irregularly, and were being played with very lazily by an irresolute west wind, so that foliage seemed to toss and ripple everywhere like green spray: but autumn was at hand, for the locust-trees were dropping a Danaë’s shower of small round yellow leaves. Around the garden was an unforgotten circle of blue hills. And this was a place of lucent twilight, unlit by either sun or stars, and with no shadows anywhere in the diffused faint radiancy that revealed this garden, which is not visible to any man except in the brief interval between dawn and sunrise.

“Why, but it is Count Emmerick’s garden at Storisende,” says Jurgen, “where I used to be having such fine times when I was a lad.”

“I will wager,” said Nessus, “that you did not use to walk alone in this garden.”

“Well, no; there was a girl.”

“Just so,” assented Nessus. “It is a local by-law: and here are those who comply with it.”

For now had come toward them, walking together in the dawn, a handsome boy and girl. And the girl was incredibly beautiful, because everybody in the garden saw her with the vision of the boy who was with her. “I am Rudolph,” said this boy, “and she is Anne.”

“And are you happy here?” asked Jurgen.

“Oh, yes, sir, we are tolerably happy: but Anne’s father is very rich, and my mother is poor, so that we cannot be quite happy until I have gone into foreign lands and come back with a great many lakhs of rupees and pieces of eight.”

“And what will you do with all this money, Rudolph?”

“My duty, sir, as I see it. But I inherit defective eyesight.”

“God speed to you, Rudolph!” said Jurgen, “for many others are in your plight.”

Then came to Jurgen and the Centaur another boy with the small blue-eyed person in whom he took delight. And this fat and indolent looking boy informed them that he and the girl who was with him were walking in the glaze of the red mustard jar, which Jurgen thought was gibberish: and the fat boy said that he and the girl had decided never to grow any older, which Jurgen said was excellent good sense if only they could manage it.

“Oh, I can manage that,” said this fat boy, reflectively, “if only I do not find the managing of it uncomfortable.”

Jurgen for a moment regarded him, and then gravely shook hands.

“I feel for you,” said Jurgen, “for I perceive that you, too, are a monstrous clever fellow: so life will get the best of you.”

“But is not cleverness the main thing, sir?”

“Time will show you, my lad,” says Jurgen, a little sorrowfully. “And God speed to you, for many others are in your plight.”

And a host of boys and girls did Jurgen see in the garden. And all the faces that Jurgen saw were young and glad and very lovely and quite heart-breakingly confident, as young persons beyond numbering came toward Jurgen and passed him there, in the first glow of dawn: so they all went exulting in the glory of their youth, and foreknowing life to be a puny antagonist from whom one might take very easily anything which one desired. And all passed in couples — “as though they came from the Ark,” said Jurgen. But the Centaur said they followed a precedent which was far older than the Ark.

“For in this garden,” said the Centaur, “each man that ever lived has sojourned for a little while, with no company save his illusions. I must tell you again that in this garden are encountered none but imaginary creatures. And stalwart persons take their hour of recreation here, and go hence unaccompanied, to become aldermen and respected merchants and bishops, and to be admired as captains upon prancing horses, or even as kings upon tall thrones; each in his station thinking not at all of the garden ever any more. But now and then come timid persons, Jurgen, who fear to leave this garden without an escort: so these must need go hence with one or another imaginary creature, to guide them about alleys and by-paths, because imaginary creatures find little nourishment in the public highways, and shun them. Thus must these timid persons skulk about obscurely with their diffident and skittish guides, and they do not ever venture willingly into the thronged places where men get horses and build thrones.”

“And what becomes of these timid persons, Centaur?”

“Why, sometimes they spoil paper, Jurgen, and sometimes they spoil human lives.”

“Then are these accursed persons,” Jurgen considered.

“You should know best,” replied the Centaur.

“Oh, very probably,” said Jurgen. “Meanwhile here is one who walks alone in this garden, and I wonder to see the local by-laws thus violated.”

Now Nessus looked at Jurgen for a while without speaking: and in the eyes of the Centaur was so much of comprehension and compassion that it troubled Jurgen. For somehow it made Jurgen fidget and consider this an unpleasantly personal way of looking at anybody.

“Yes, certainly,” said the Centaur, “this woman walks alone. But there is no help for her loneliness, since the lad who loved this woman is dead.”

“Nessus, I am willing to be reasonably sorry about it. Still, is there any need of pulling quite such a portentously long face? After all, a great many other persons have died, off and on: and for anything I can say to the contrary, this particular young fellow may have been no especial loss to anybody.”

Again the Centaur said, “You should know best.”

Footnotes from Notes on Jurgen (1928), by James P. Cover — with additional comments from the creators of this website; rewritten, in some instances, by HiLoBooks.

* “Danaë’s Shower” — While Danaë was confined in a brazen tower by her father, Zeus descended to her in a shower of gold, and she gave birth to Perseus.

* “Count Emmerick” — Emmerick, the only son of Dom Manuel to be born in wedlock, figures very slightly in the legends of Poictesme. He is introduced into Book First of Cabell’s The Cream of the Jest (1917); and, in The Silver Stallion (1926), reigns rather weakly over Poictesme, at first under his mother as regent, and later under the dominance of his somewhat elderly wife.

* Storisende — This is probably “story’s end.” The use made of the castle in The Cream of the Jest, where it is first introduced into Mr. Cabell’s books, strengthens this interpretation.

* Rudolph and Anne — This is Rudolph Musgrave and Anne Willoughby, afterwards Anne Charteris. For the history of this couple see The Rivet in Grandfather’s Neck.

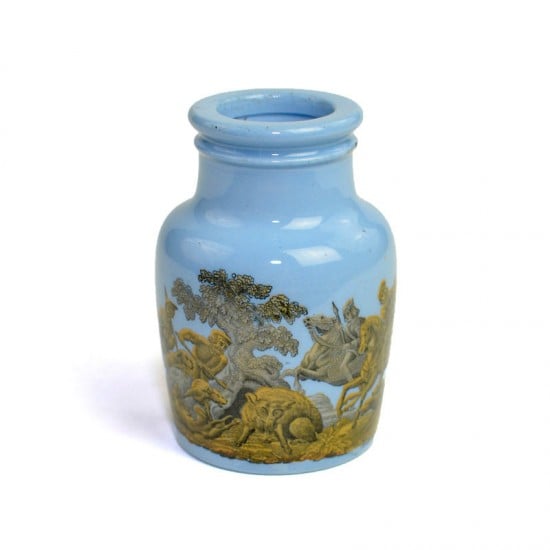

* The Red Mustard Jar — The two who are “walking in the glaze of the red mustard jar” are Robert Townsend and Stella Musgrave. For this couple see The Cords of Vanity: “‘You silly! it means, of course, that Ole-Luk-Oie is kind, and has put us both into the glaze of the mustard-jar — only I wonder which one we have gotten into?’ Stella said. ‘Don’t you remember them, dear — the blue mustard-jar and the red one your Mammy had that summer at the Green Chalybeate, with men on them hunting a boar?'”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”