10 Best Adventures of 1935

By:

March 8, 2015

Eighty years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Thirties Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. I urge you to read them immediately.

Note that 1935 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Thirties. The transition away from the previous era (the Nineteen-Twenties) begins to gain steam….

The year 1935 was the second year of science fiction and fantasy’s so-called Golden Age… and its first non-cusp year. The year 1934, that is to say, was a cusp year between sci-fi and fantasy’s Radium (1904–33) and Golden (1934–63) Ages; during 1935, then, Golden Age memes and themes begin to emerge more distinctly.

Note that the following titles are listed in no particular order.

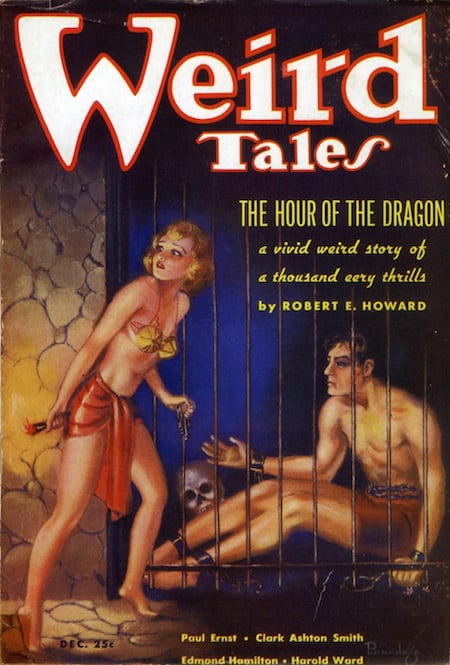

- Robert E. Howard’s atavistic fantasy adventure The Hour of the Dragon. During Conan’s reign as King of Aquilonia, conspirators resurrect an ancient sorcerer, with whose aid the rival kingdom of Nemedia invades and occupies Aquilonia. Rescued by a slave girl, Conan embarks on a quest to retrieve a magical artifact that will allow him to defeat the wizard. Serialized in the pulp magazine Weird Tales, then published in book form (in 1950) as Conan the Conqueror, this is Howard’s only full-length novel about his Cimmerian antihero.

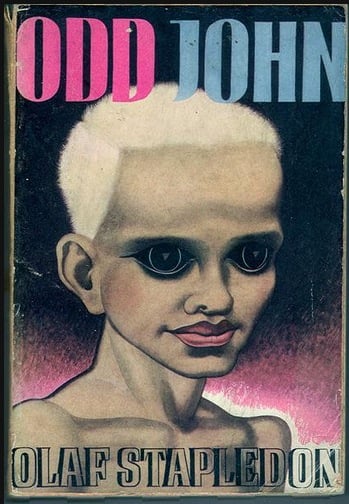

- Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John. An extraordinary novel — by a visionary author who helped usher in Radium Age-era sci-fi themes and memes into the genre’s so-called Golden Age — which deserves to be much better known. Led by a teenage mutant “supernormal,” Odd John, a group of evolved misfits form an island colony. There, they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, “intelligent worship,” and “individualistic communism.” The jacket illustration shown here captures Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless but not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.” The novel’s narrator, who has observed John growing up, and who is the only un-evolved human permitted to visit the island, isn’t sure whether to be overjoyed or terrified about what the “wide-awakes” are planning. Fun fact: Matthew De Abaitua’s terrific 2015 sci-fi novel If Then is, in certain key respects, an example of Stapledon fanfic… complete with a WWI-era homo superior known as Omega John.

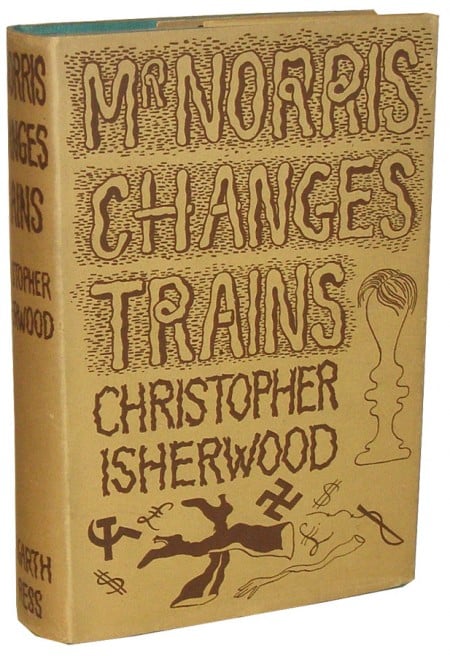

- Christopher Isherwood’s espionage adventure Mr. Norris Changes Trains. Not exactly an adventure — except, I guess, in the sense that say, Ian Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me (another short novel in which the narrator, a naïf, doesn’t understand until the end what’s been going on). But this is a very misleading comparison. The secret agent character, Norris, is the anti-James Bond: He’s ugly, effeminate, a masochist and pornographer, and a Communist (or so he claims). The narrator, meanwhile, is a naïf but no innocent: He’s an ironist, a disengaged aesthete. Perhaps a better comparison would be with Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, because like Greene’s titular character, the narrator of Mr. Norris Changes Trains is an ex-pat in search of adventure in a foreign country… and for whom prostitution, drug abuse, and poverty are so much scenery.

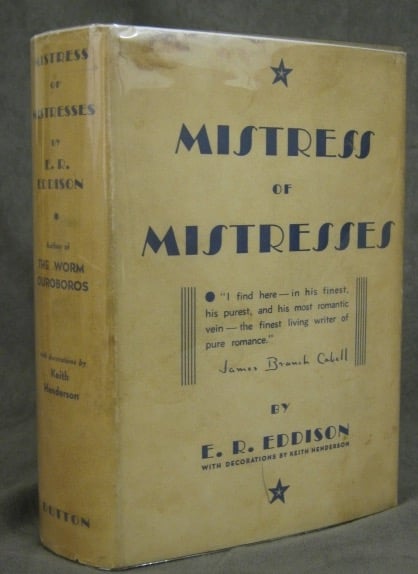

- E.R. Eddison’s fantasy adventure Mistress of Mistresses. More admired than read, Mistress of Mistresses doesn’t boast much in the way of a plot, and the ornate language can be a chore, but it’s a smart (if eccentric) work of philosophy and a gorgeous vision of an imaginary planet. Following the death of Zimiamvia’s king, the nobles of the realm begin to intrigue; but the author doesn’t require us to decide which side of the conflict is good or evil — at least, not until halfway through the story. Our protagonist, Lessingham, is part Burroughsian action hero (who exists simultaneously on Earth and this planet), part aesthete; he contends with enemies and enchantments. Fantasy exegetes credit Eddison with having brought detailed geographies, complex historical back-stories, epic violence, and an obsession with linguistics to the genre; no wonder that Tolkien called him “the greatest and most convincing writer of invented worlds that I have read.”

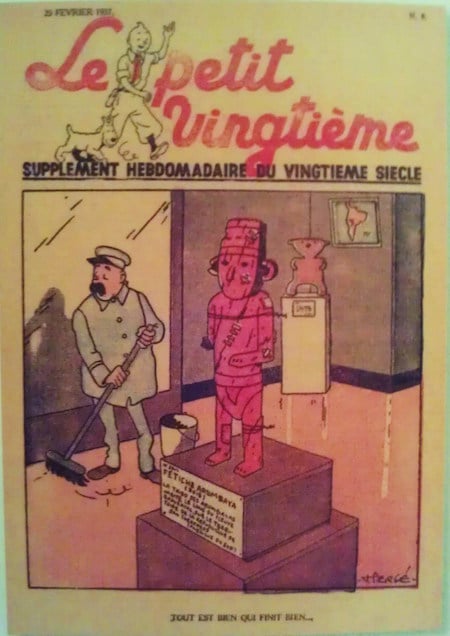

- Hergé’s crime-, Ruritanian- and frontier-type Tintin adventure The Broken Ear. Serialized in 1935–7, and published as a color album in 1943. Young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog, Snowy, pursue the thieves of a Arumbayan fetish to the fictional South American nation of San Theodoros (based on Bolivia). Once there, the story’s resemblance to Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon ends. Tintin is framed as a terrorist and sentenced to death; however, his life is spared when a revolution led by General Alcazar (who appears in future Tintin adventures, too) topples the government. Threatened by western businessmen eager to profit from the civil war, Tintin flees into the jungle, where he discovers a British explorer living among the Arumbaya tribe… and finally learns the secret of the Arumbayan fetish.

- Dorothy L. Sayers’s crime adventure Gaudy Night. Although I don’t read many murder mysteries, I’m a big fan of Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey adventures. In Strong Poison, Wimsey clears murder writer Harriet Vane of murder charges, and proposes marriage; she rejects him. In Have His Carcase, Vane and Wimsey collaborate on an investigation; she continues to reject his advances. In this adventure, which is a campus novel, a psychological thriller, and a philosophical novel rolled into one, while pretending to research the Gothic adventure writer Sheridan Le Fanu, Vane investigates troubling pranks and incidents targeting intellectual women at her alma mater — one of the colleges at Oxford. Despite what the cover shown here suggests, Wimsey doesn’t appear until late in the story. Will Harriet finally return his affections?

- John Dickson Carr’s crime adventure The Hollow Man. Published in the US as The Three Coffins. Considered one of the best — if not the best — locked-room mystery novel of all time, The Hollow Man has a complex plot I won’t try to tease out here. Except to point out that there are actually two “impossible” murders in the story: Grimaud is shot in a locked room, but the gun is missing; and his brother, Fley, is later shot in a cul de sac — with the same gun — although there are no tracks in the surrounding snow but his. Fun fact: The appearance and personality of the character Dr. Gideon Fell, who at one point lectures on the various ways one might commit an “impossible” murder, is supposedly based on G.K. Chesterton. Fell, who was protagonist of five previous Carr mysteries, would go on to star in another 17.

- Conrad Aiken’s crime adventure King Coffin. A psychological thriller about a would-be Nietzschean obsessed with committing the perfect crime — the murder of a complete stranger. Set in Boston and Cambridge among a bohemian milieu of anarchists, artists, and intellectuals. Fun fact: Aiken was a highly decorated poet, winner of the National Medal for Literature, the Gold Medal for Poetry from the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Prize, and the National Book Award. What’s more, his daughter, Joan Aiken, is one of the greatest authors of adventure lit for older kids of the Sixties.

- John P. Marquand’s Mr. Moto espionage adventure No Hero. Also known as Your Turn, Mr. Moto and Mr. Moto Takes a Hand. Originally serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1935; this is the first of six Moto novels (1935–67), and numerous stories. As in most Moto stories, here an American male (Casey Lee, a WWI ace pilot) finds himself in the Orient and gets involved in an international intrigue (the Japanese Emperor’s expansionist plans for his country). He finds himself in peril, meets a beautiful woman (a White Russian refugee), and — thanks to the appearance of Japanese secret agent Mr. Moto at opportune moments — escapes safely. Fun fact: Marquand won the Pulitzer prize in 1938 for his novel The Late George Apley. He also wrote one of the best adventures of 1925.

- C.S. Forester’s frontier adventure The African Queen. In 1914, as WWI begins, the German military commander of Central Africa conscripts all the natives, leaving Rose Sayer, a highbrow spinster missionary, with nothing to do but tend to her dying brother… who dies. Allnutt, a lowbrow bachelor mechanic and skipper, shows up and takes Rose to his steam-powered launch, the unreliable African Queen. If you’ve seen John Huston’s 1951 Bogart-Hepburn movie of the same title, then you know more or less what happens next. The book’s ending, however, is more ambiguous and downbeat. Fun fact: Forester would go on to write the enduringly popular 12-book Horatio Hornblower series (1937–67), depicting a Royal Navy officer during the Napoleonic era.

Let me know, readers, if I’ve missed any 1935 adventures that you particularly admire.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.