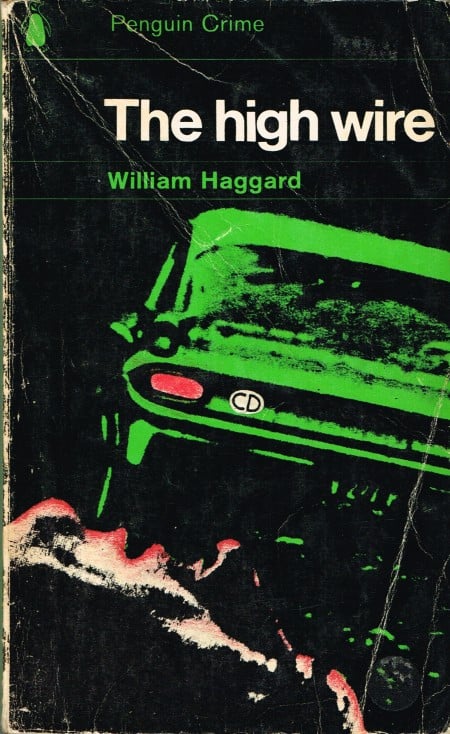

The High Wire (16)

By:

February 17, 2015

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize William Haggard’s 1963 novel The High Wire, the fifth title in his acclaimed Col. Charles Russell espionage adventure series — which, at the time, was considered by critics (if not the general public) superior to Ian Fleming’s Bond series. “Haggard lacked Fleming’s snooty dilettantism, and was better at creating subtle layers of political intrigue,” Christopher Fowler has written. “Haggard treats his women with more respect, too. They are investigators and heroines with lives of their own. As for exoticism, try Haggard’s character Miss Borrodaile, the elegant, black-clad, former French Resistance fighter with a steel foot.” Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The High Wire as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Recollecting his emotions later, in the tranquillity which was supposed to be art but wasn’t, Rex was grateful that at least Victor had spared them histrionics. The temptations of a certain melodrama must have been considerable, and a lesser man might easily have indulged in them. But Victor had not. As the relief car slid away again he spoke with a brutal directness. ‘My name doesn’t matter, nor my job.’ He looked at Rex Hadley but the pistol was still on Mary. ‘Yours does. You’re the head man at Maldington and Maldington has something. An American called Danziger has flown across to talk of it. I want it too and I mean to get it.’

Rex didn’t reply. He had picked himself off the floor and Victor, not moving his pistol hand, had nodded at one of the benches. Rex Hadley sat down. For one thing he hadn’t his breath back and for another he needed to think. The situation had a clarity which one part of his mind approved. According to Robert Mortimer there was the head of a foreign state who would give his eyes for an equal knowledge of Project A, and his agents had already tried twice. On both occasions Rex had himself been their target. The first attempt he hadn’t known about till Mortimer had told him, and the second — well, the second had undeniably shaken him. But though it had shaken it had also prepared him. This powerful-looking stranger with the formidable in-fighting and the steady gun would be yet another agent of the same head of state. Rex was glad that he wasn’t surprised since he knew that if he had been he would also have been frightened.

But though he wasn’t frightened yet he didn’t know what to do. He had fought in a war and he had recently and forcibly been reminded of it. But he knew nothing of man-to-man fighting, nothing of pistols and of the tricks which he had read could sometimes neutralize them. Sometimes, though, and with great good luck, for nobody pretended that a man with a pistol who knew how to use it hadn’t an advantage against even an expert at unarmed combat. And Rex wasn’t an expert at all; he couldn’t even assess the risks. The cabin was very small (for all he knew that might weigh against the pistol-man) and there was an uncovenanted complication. The pistol was on Mary and not himself. What did the expert do when the gun was on another man, a woman, Mary…?

But Victor was talking again, laconic and menacing. ‘I want it,’ he repeated. ‘The secret. And I’m going to have it.’

The cool moonlight in the little car was shattered by a searchlight. It was suddenly as bright as day. Victor laughed shortly. ‘That will be Maraldi. Much good may it do him.’ He was entirely confident.

And, Rex decided, rightly. The sides of the cabin, below the glass windows, were steel, but they wouldn’t shoot through them in any case, not more than half blindly. And for a shot through the window the angle was hopeless… or was it? he wondered. Victor was standing, and for a very good shot the top of his head… Just possibly…

But Victor had seen it too, sat down again. He sat on the single seat, Mary to the left of him, Rex to the right. ‘Tell,’ he said dourly. ‘Tell.’

Rex lit a cigarette. Now he was frightened but he was also pleased. His hand hadn’t shaken or not very much.

‘But that was cheap, but that was foolish. If you think you can bluff me —’

Victor had begun to snarl. He switched the gun at Rex’s stomach.

Mary said softly: ‘Hold, Rex, hold.’

‘Hold! You impertinent fool.’ Victor was blazing now. ‘You amateur.’ It was the worst word he knew.

He flicked the gun back at Mary.

From the gulley below there was a sharp report. Rex waited for the bullet’s whine but never heard it. Instead something snaked past the window, falling across the bearer wire, over the cabin but outside it. When it had settled Rex saw it was a rope.

Victor laughed contemptuously. ‘Rocket escape-line — useless. You could reach that rope and pull on it. Up would come a bigger one, a rope ladder perhaps. You could get down if you had the nerve, or another man could climb up. Another armed man. All this could happen if you could reach that line. You won’t, of course. We’re quite alone — we’ll stay so.’ Victor was talking calmly now. His sudden rage was spent.

Rex looked at him. He much preferred him angry. Now he was master and knew it, talking again smoothly: ‘I don’t care how tough you think you are, how many cigarettes you smoke. I’ve broken brave men and I’d break you too. In time, that is — directly. But I needn’t waste time, I’m not obliged to. This woman here…’

He looked from Rex to Mary. The gun was already on her. She said something in French.

There was a single shot.

For a moment Rex didn’t register. Mary was bending down. She had taken a foolish handkerchief from an even more frivolous bag; she was tying her leg up silently. Rex watched her in a sort of dream, half seeing her. What he saw was a handkerchief, red.

He rushed Victor by instinct, swinging absurdly, and in an instant he was flat again. He staggered across the little car, crashing against the opposite side, smashing the glass and falling. He hadn’t been shot but he wished he had. His hands were between his legs, holding his crutch helplessly. Enormous waves of agony came up at him, black ones, then scarlet. He couldn’t breathe and he couldn’t move. He wished he could die but he knew he mustn’t. He fought for his life.

Victor was standing over him but the pistol was still on Mary. She hadn’t moved nor spoken again. Victor’s face was a stone. ‘Talk,’ he said wickedly. ‘Talk for your lady love.’

Francis de Fleury had passed three days in an increasing awareness of futility. It had been one thing to keep close to Victor, something which could be done quite openly since Victor himself was being watched by professionals and could hardly complain to them that a freelance had cut in; but Rex Hadley and Mary were much more difficult, not amateur’s work at all. He hadn’t been trained in shadowing and they’d spot him at once. They wouldn’t go to the police, they’d simply challenge him…. What in hell did he think he was playing at?

De Fleury sighed. Besides, he thought, he would be watching blind. For what? For Victor’s return? He considered it unlikely, since he could think of nothing which couldn’t equally well be carried out by one of Victor’s men. And probably better. Victor had been here to scout, not act. So de Fleury would be watching for someone he didn’t know, some plan he hadn’t an inkling of. Instinct insisted that there would be further violence and de Fleury respected instinct; but reason told him coolly that he himself was useless. Only his pride had kept him in Sestriere. He had told Robert Mortimer he intended to stay and that was an undertaking.

Which was something one stood by.

On Friday evening he had been drinking an aperitif when all the lights went out. It didn’t strike him as significant — power lines did fail, especially mountain ones — but he had been irritated. They had been slow with the candles in the bar, and presently he saw that there were lights again in the ski club. Probably they had batteries. He left money on the table and walked idly across the square. He pushed the door open.

At once he knew that something had happened. An attendant was talking to an increasing crowd of tourists. There was a car up there — stuck. Of course it was quite all right. Three people on a special trip but they’d get them down in no time. They had put on the relief car and the engineer was starting up the diesel. There was nothing to worry about, nothing at all. Routine.

Suddenly the hall was full of police. Their plain-clothes leader cut through the crowd, straight to the attendant.

…Three people in the car up there? What people?

An Englishman and his wife.

Staying at the Conte?

Yes.

A second’s silence.

And the third person with them?

An elderly man, a foreigner.

Describe.

Sixty to sixty-five. Thickset and powerful. He had been here before but had left and returned. He’d altered his appearance, dyed his hair….

There was an oath but a further question. Then where had the car stuck?

Just at the bottom, above that gulley.

Another oath but instant action. Maraldi swung on the policemen…. The searchlight, the rocket-gear. Run.

They ran.

De Fleury saw that Robert Mortimer had joined Maraldi. He slipped quietly across to them, listening. Maraldi was saying savagely: ‘He’s got them alone — the two of them. Victor himself. They’re up in that stalled cable-car.’

‘You’re certain it’s Victor?’

‘Morally.’

Robert said softly: ‘Is that a fact?’

‘You don’t seem to understand me. If it’s Victor himself —’

‘I understand you perfecdy. So how do we bring them down?’

‘They’re putting on the rescue car.’

‘I’ll go in it then.’

‘I’ll go.’

Robert said patiently: ‘Think. I heard you giving orders and there’s plenty to do down here still. You’re head man here and I don’t count. We don’t want a panic and we don’t want the Press. You cut the ice, I don’t.’

‘Mother of God, I —’

‘Get this mob out of here. Go down to the gulley with the searchlight. Try the escape-line, though it doesn’t sound hopeful. Take charge. Use your loaf.’

Maraldi hesitated and Robert pushed him gently. At last he shrugged and turned.

The police began to clear the hall, but de Fleury touched Robert Mortimer. ‘Hullo.’

‘Oh, hullo.’

‘I’ve been eavesdropping.’

‘Yes, I saw you.’

‘I’d like to go along with you.’

‘But why?’

‘I told you that once.’

‘You’re a very strange sort of blackmailer.’

De Fleury said furiously: ‘People are always telling me I’m strange. I simply don’t see it. Mary Francom is up there, with Victor —’

‘I’m afraid there won’t be room for you.’

‘But —’

Robert looked deliberately at the two carabinieri still in the hall. ‘But you can stay here,’ he said. ‘I’ll tell them.’

He did so, turning, walking out to the platform and the waiting relief car. De Fleury began to pace the hall — eight strides, a turn, and eight again. He wa”s lighting one cigarette from another.

Twenty minutes later Robert had come back again. He was supporting the attendant. ‘Nothing too serious. A shot in the shoulder. Lucky.’ One of the carabinieri led the attendant away, and Robert walked up to de Fleury. ‘I suppose,’ he said mildly, ‘I suppose you can’t lend me a gun? They’re tying a sort of shield to the relief car — the top of the oil tank, I think it is — but it’s better than nothing.’ He looked at the remaining carabiniere. ‘That bobby will have a pistol but it’s not one I’m used to. Me, I never carry one but we all know you do. They frisked your room.’ Unexpectedly his voice was almost wheedling. ‘Now that nice little Colt of yours, or Luger…’

Very slowly de Fleury put his hand in his pocket, and when it came out it was holding a gun. It was holding it by the barrel and Robert approved. He put his hand out to take the butt, smiling his thanks, and for a second he was off balance.

De Fleury knocked him cold.

The cabariniere began to move, but now the gun was pointed.

‘Keep very still.’

De Fleury ran across the hall, out through the glass partition doors, on to the platform. In the control room the engineer could see nothing of the hall; all he saw from his window was that the shield had been lashed to the relief car and that a man had just jumped into it. An armed man who waved at him urgently. He pulled a lever and the relief car began to move.

Francis de Fleury let his breath out softly.

He sat down in the open box, behind the makeshift armour, coolly assessing his chances. They weren’t, he decided, brilliant. The top of the oil tank, though only iron, would probably stop an ordinary pistol bullet, but he had nothing to fire through and the shield wasn’t more than four feet high. The relief car itself hung well below the bearer-wire — a man being rescued dropped into it from the cable-car — and that meant that Victor would be shooting down at him. He was safe enough crouched behind his improvised gun-shield and provided he kept a respectful distance, but he didn’t propose to spend a night crouched uselessly behind a gun-shield. He’d have to stand up to shoot, to kneel at best, and that meant exposing head, chest and shoulders. Whereas Victor, shooting down at him, would show him two eyes, a pistol hand at most at the cable-car’s open window. And below it was solid steel.

Francis de Fleury smiled. And that wasn’t all of it. The mountain weather, notoriously unpredictable, had turned against him. Now the moon was behind a sudden cloud; a cold wind blew in fickle gusts. The car had begun to swing — not dangerously, but it would be a very poor platform for a gun duel. The cable-car might be swinging too but, heavier, much less.

De Fleury looked at his gun. Guns were a hobby. This one, he remembered, was his second. Mary had taken the first — Mary in that cable-car with Victor.

He stood up without knowing it, staring into a sudden blur of snow. He had come perhaps half-way, and, as the flurry cleared, he could see the cable-car ahead of him. The searchlight lit it mercilessly. It hung on a single wire, a tiny world and quite alone, white in the searchlight’s glare.

Another squall rocked the rescue car and de Fleury sat down. As he did so the walkie-talkie buzzed at him. He picked it up unthinkingly and a cool voice said crisply: ‘Robert Mortimer here.’

‘Don’t stop the wire, I beg you. Please.’

There was an incomprehensible English laugh. ‘My friend, I wouldn’t think of it. There isn’t time to wind you in, and I’m in no shape to take your place.’

‘I’m sorry about that, I —’

‘Forget it. And good luck.’

The walkie-talkie went dead and de Fleury stood up again. He was sixty yards away by now, but the angle was against him, as were the cable-car’s steel sides. Even standing he couldn’t see into it. In any case he’d have to make Victor shoot at him. He couldn’t just run up to them, try to climb in, to board them. That would be suicide. He’d have to fire first — draw fire. Victor wasn’t a man to be shot at without answering. So one into the cabin first, through the open back window, upwards. And pray it wouldn’t ricochet. The roof might be wood, or lined….

He’d have to risk it.

He fired as a third squall struck him, squarely now. The shot went away, but uselessly, even the report lost in the screaming wind. The open car swung wildly and de Fleury fell to save himself. He felt sick but he was still quite calm. Swinging like this, a human pendulum, he wouldn’t hit a haystack. And the car was running on still. Forty yards now, no, less….

He picked up the walkie-talkie again. He told Mortimer to stop him.

When the rescue car stopped at last de Fleury peeped out of it. Now it was ten yards. The range had shortened but not the odds: on the contrary they had lengthened, and against him. He was much too close and much too low. Victor, when he shot at him, would be a fancy target indeed. And the shield was useless now.

Francis de Fleury laughed. He was a sitting duck and knew it. Well, at least he needn’t fire again; he needn’t waste bullets attracting attention.

He stood up yet again as the car for an instant steadied; he filled his lungs with icy air and shouted.

‘Victor.’

Nothing.

‘Victor, you bastard swine.’

There was the flicker of a target, eyes and a hand. De Fleury fired and the cruel wind jerked the rescue car. He knew he had missed but Victor hadn’t. He’d been going for the body and he’d got it. De Fleury collapsed. He had dropped the gun but it had fallen under him.

…Victor wouldn’t see it there, he’d think it had gone overboard. There was a chance he wouldn’t shoot again…. A man in a little box, sprawled on his face, dead probably and anyhow disarmed….

Victor was a peasant and he hated waste.

De Fleury lay very still. He was hit pretty badly but he wasn’t dead.

When he was sure no second shot was coming he felt for the pistol and dragged himself to his knees. He was bleeding internally and very cold. He forced himself upright, groaning softly, holding the shield for support, focusing the cable-car through mists of pain. He gave himself a minute more of consciousness — a minute and a half at most. Then he would be out for good.

In the lull in the wind he fired a third shot at nothing. At that range it must be heard.

In the cable-car Victor had returned to Rex and Mary. Killing de Fleury hadn’t given him a twinge. The man had always been a playboy, not worth a thought, and now it was certain he’d changed sides. The rat — he’d earned his bullet. But though de Fleury hadn’t worried him Victor was worried. The affair wasn’t developing as he had expected. Mary was sitting quietly — much too quietly to suit Victor. He had hoped for hysteria, for tears at least: her contemptuous silence shook him for it didn’t suit his plan. With a shinbone smashed she hadn’t uttered. She wasn’t helping him at all, she wasn’t playing. She might have been at her hairdresser’s.

…All right, he’d show them. They thought they were tough, but he’d seen brave men and women pitiably broken. He himself had done the breaking. He raised the gun again, sighting at Mary’s shoulder now, but lowered it. It would be premature to shoot again since Rex couldn’t speak yet. He’d keep that for when he could — for when it paid. He looked down at Rex Hadley, writhing, fighting for breath and more, his hands between his legs still, holding himself together. Time, Victor remembered suddenly, was running against him. Sooner or later they’d manage to pull the car down.

A lifetime’s discipline cracked in insane frustration. To plan and to come so close; to offer his own freedom up, the rest of his life in prison. He almost wept. The fools, the unaccountably stubborn fools. This grovelling thing on the floor, this crippled Englishman….

Victor balanced himself carefully, raising his right foot. He was aiming at Rex’s hands. It would kill him of course, so he’d never talk.

For an appalling instant it didn’t matter. Victor swung his foot once slowly, measuring the final blow. His face was a mask of hate.

Deliberately he dropped his knee again. Outside the cable-car he’d heard a shot.

It sobered him at once. This was another interruption, something to be attended to, and finally. He turned his back on Rex and Mary for he didn’t fear either: he turned his back but he also bent it. On this side of the car no bullet could reach him, but as he moved across it to the window…. A target perhaps, a second’s target.

He slipped across the cable-car bent double, checking his gun as he went, and behind the steel below the window he collected himself…. Up for an instant, sight and shoot. He’d finish it this time, he couldn’t miss.

He heard movement behind him and turned his head, incredulous. Rex Hadley was coming after him. If that was what you called it. He was dragging himself by his elbows, his legs hanging uselessly behind him, like a reptile, Victor thought unexpectedly, the lowest of creation. He watched in fascination. Rex was gasping, in evident agony…. Heave on an elbow, gasp, and wait. His face shone with sweat. Another heave, another bitter foot, and wait again. Only his eyes were steady and they never left Victor’s.

Victor raised his gun but dropped it. He was sane again now. Killing Hadley would be fatal. He put the gun back in his pocket.

He waited impassively as Rex inched towards him. Then he bent down a little more, grasping his coat collar. He had only one arm but it was very strong. He pulled Rex on to his knees and somehow he stayed there. Rex struck weakly at Victor’s belly, an overarm swing, feeble and in any case outranged. Victor ignored it. He drew back his own good arm, instinctively straightening.

The blow never fell. Victor dropped inexplicably, down on Rex Hadley, knocking him off his knees again. Rex lay quite still, grimly awaiting further punishment. None came. When Victor didn’t move again Rex pulled himself back on his elbows. It was the last of his strength. Victor lay motionless. He was lying on his face and he was dead. There was a neat small hole in the back of his head and Rex didn’t try to turn it.

Somehow he found breath once more. ‘Mary… the rescue line… pull it in.’

Through a blur of receding consciousness he saw that she had heard him. She had risen on her single leg, steadying herself against the cable-car’s side. She hobbled to the window his first fall had shattered and at least reached the line. She began to pull it in. There seemed to be a mile of it but finally a rope came up — two ropes, a ladder. Mary made it fast and Rex saw it tauten.

‘There’s a man climbing up.’

Rex didn’t hear her.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”