10 Best Adventures of 1925

By:

January 31, 2015

Ninety years ago, the following 10 adventures — I’ve plucked these titles from my Best Twenties Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. I urge you to read them immediately.

Note that 1925 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Twenties. The transition away from the previous era (the Nineteen-Teens) begins to gain steam….

- Earl Derr Biggers’s crime adventure The House Without a Key. The author was best known, at the time, for his 1913 semi-comical thriller Seven Keys to Baldpate; it was adapted into a hit Broadway play and several films. In 1924, Biggers read about the exploits of Chang Apana, a shrewd, tenacious Chinese-Hawaiian detective in the Honolulu Police Department; he inserted a similar character into the thriller he was writing at the time. The House Without a Key, set in Hawaii, became the first in a series of six immensely popular Charlie Chan novels. Fun Fact: Except for Sherlock Holmes, for some years Charlie Chan — who was, in part, designed to counteract the British adventure’s tradition of the sinister, untrustworthy Oriental; but whose mannerisms and habits of speech cannot but help make today’s enlightened reader wince — was literature’s best-known sleuth.

- Blaise Cendrars’s treasure hunt adventure L’Or (Sutter’s Gold). Though today we’ve placed him on a highbrow pedestal, emblazoned with the legend, “First Modernist Poet,” in fact Cendrars was a feral high-lowbrow. In 1913, for example, he declared: “I like legends, dialects, mistakes of language, detective novels, the flesh of girls, the sun, the Eiffel Tower.” (He also liked science fiction: His Kodak was a pastiche of lines from his friend Gustave Le Rouge’s The Mysterious Doctor Cornelius.) L’Or, translated in 1926 as Sutter’s Gold, is a fascinating example of Cendrars’s blagueurie. Ostensibly a historically accurate novel about Sacramento pioneer John Sutter, on whose land was discovered — for better and worse — the ore that sparked the California Gold Rush, in fact the novel is sardonic inversion of adventure’s Robinsonade sub-genre. At the same time, it’s a cinematic, rhapsodic western!

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical science fiction adventure The Fatal Eggs. In a near-future (or perhaps alternate-history) Moscow, the zoologist Vladimir Ipat’evich Persikov discovers a ray that causes frogs and other organisms to mature and reproduce at a rapid rate. At the same time, however, a disease wipes out all of Soviet Russia’s domesticated poultry. Persikov’s equipment is confiscated by the authorities, and thousands of chicken eggs are sent to his laboratory… so that the ray can be used to regenerate the country’s chicken population overnight. Unfortunately, a mixup causes snake and crocodile eggs, instead of chicken eggs, to be treated with the growth ray. Catastrophe! Is the novel a satire — cf. Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita — of the leadership of Soviet Russia? Certainly, some critics at the time suspected as much. However, the novel (novella, really) is squarely in the tradition of western science fiction — from Frankenstein to H.G. Wells’s The Food of the Gods, say — which warns arrogant scientists not to meddle too deeply in nature’s mysteries.

- James Boyd’s historical adventure Drums. Only an adventure in parts (there’s a a John Paul Jones sea battle, among other exploits at sea), Drums is told from the viewpoint of a North Carolina Tory gentleman’s adolescent son, who is reluctantly drawn into the drama of the American Revolution. The author, who’d served overseas with the Army Ambulance Service in World War I, does not glorify the Revolution; nor does he shrink from depicting the harsh realities of a slave state. His protagonist, Johnny Fraser, like Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, does not at first question the institution of slavery; nor does he assume that the revolutionaries’ cause is just. The scenes of violence are realistic. The historian David McCullough has said that reading this novel — no doubt in an edition illustrated by N.C. Wyeth — as an adolescent inspired him to become a historian; and it’s been called the best novel written about the American Revolution. Decide for yourself!

- Liam O’Flaherty’s hunted-man adventure The Informer. Not long after the 1919–21 Irish War of Independence, and 1922–23 Irish Civil War, two ex-members of the revolutionary Communist Party of Ireland meet in Dublin. One of them, Frankie McPhillip, has been hiding from the police, but — because he’s dying of consumption — has returned to see his family once more. The other, dim-witted Gypo Nolan, has been struggling to make a living. Gypo informs on McPhillip to the police, in exchange for a reward — and then, when McPhillip is killed, his horrified former comrades assign Gypo the task of figuring out who the informer is! (Cf. Kenneth Fearing’s 1946 thriller, The Big Clock.) It’s a brilliantly written tale, suspenseful yet not without comic moments. John Ford directed the 1935 film version.

- S. Fowler Wright’s science fiction adventure The Amphibians. Published first in 1924, then reissued in 1925 with the author’s improvements, then reissued again in 1929 — with additional chapters — as The World Below, Wright’s story is a Radium Age Superman parable, and a Divine Comedy-esque trek across a landscape of horrors. A time traveler half a million years in the future discovers that the Earth is a battleground between two species. The Dwellers are humanoid giants with equally giant intellects, self-destructively devoted to science; the Amphibians are furry, dispassionate types who take the long view. Fun Fact: Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.”

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical science fiction adventure Heart of a Dog. Written in 1925 and circulated in samizdat until after the fall of the Soviet Union, this thriller that mostly takes place inside a single Moscow apartment. Professor Filipp Filippovich Preobrazhensky, a Dr. Moreau-like figure, and his assistant, Dr. Bormenthal, implant the sexual organs and pituitary gland of an evil man into Sharik, a well-behaved dog. The scientists believe that they are imposing a progressive scientific system upon the Russian people; indeed, the resulting creature, a lout named Sharikov — succeeds all too easily in Soviet society. Is Bulgakov’s story a satire on Communist attempts to create a New Soviet man? No doubt. It’s also another homage to H.G. Wells.

- J.P. Marquand’s treasure hunt adventure The Black Cargo. Marquand, the Pulitzer-winning author of The Late George Apley (1937), not to mention six popular Mr. Moto crime/espionage adventures (1935–57), got his start writing historical “costume” adventures for the Saturday Evening Post. Through the 1940s and ’50s he had the longest string of bestsellers of any American author; I’m not a fan of most of them. However, I do enjoy this example of Marquand juvenilia (it’s his second novel) about derring-do and the illicit slave trade set in a colonial seaport — Marquand’s hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts — and on Yankee trading ships in the Pacific. A fun yarn.

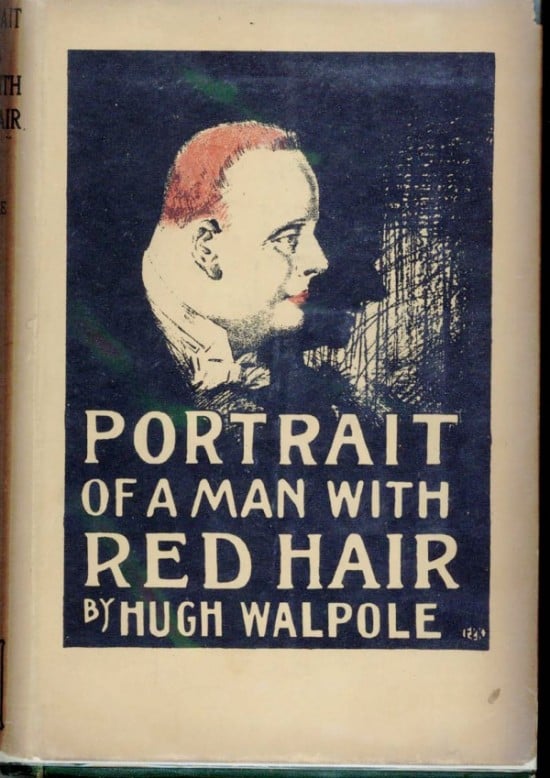

- Hugh Walpole’s gothic adventure Portrait of a Man with Red Hair. Walpole was one of the most popular authors of his time, and praised by everyone from Henry James to John Buchan. I’m a fan of his 1919 adventure, The Secret City, which drew upon the author’s experience as head of the Anglo-Russian Propaganda Bureau during the Russian Revolution; and of his 1930 historical adventure Rogue Herries. Of this fast-paced macabre horror novel, in which a sensitive young man must overcome a sadistic ghoul, not to mention his own too-civilized sensibilities, in order to survive and rescue the woman he loves, Walpole told a friend, it’s “a simple shocker which it has amused me like anything to write, and won’t bore you to read.” This is an understatement.

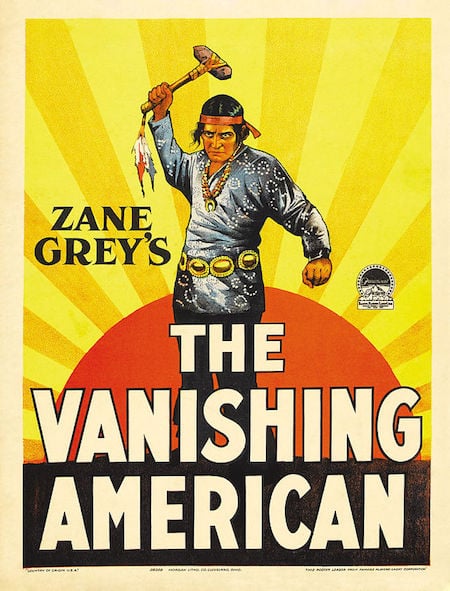

- Zane Grey’s revisionist western adventure The Vanishing American. Serialized in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1922–23, The Vanishing American — whose protagonist, Nophaie, is a Nopa (Navajo) who’d been kidnapped as a child and raised by whites — offers a scathing indictment of the government agents and missionaries who preyed upon Native Americans. Although he becomes a Jim Thorpe-like superstar athlete and scholar, Nophaie longs to help his people, whose way of life is threatened; can he dissuade them from rising up and going on the warpath? The book version of Grey’s story was published in 1925, the same year that Paramount’s ambitious film adaptation appeared; both were toned down — instead of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the villain became a single corrupt individual.

Please note that these are not listed in any particular order.

Let me know, readers, if I’ve missed any 1925 adventures that you particularly admire.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.