Bowieology (6)

By:

January 13, 2015

Sixth post in a series of seven, surveying David Bowie’s cultural contributions as he enters his second 50 years of acceptance and transgression.

Black Tie had in fact succeeded in Bowie’s U.K. homeland, knocking out the Bowie disciple band Suede to debut at #1, and he chose to release his next album there only (at first). The Buddha of Suburbia (1993) was a suite of songs built from Bowie’s soundtrack to the BBC TV mini-series of same name, based on British author Hanif Kureishi’s tales of tragi-comic culture-collision in the ’70s. The album’s recombinant grab-bag of nostalgic sounds was an earnest yet inert exercise, and is memorable mostly for Bowie’s liner notes, a loopy Anglocentric screed in which he takes a bizarre stab in the literary arena at the kind of cultural criticism he can imply so much more eloquently in his art.

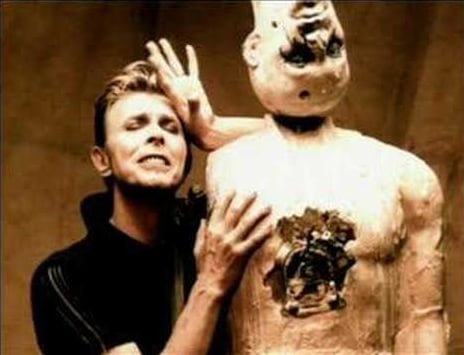

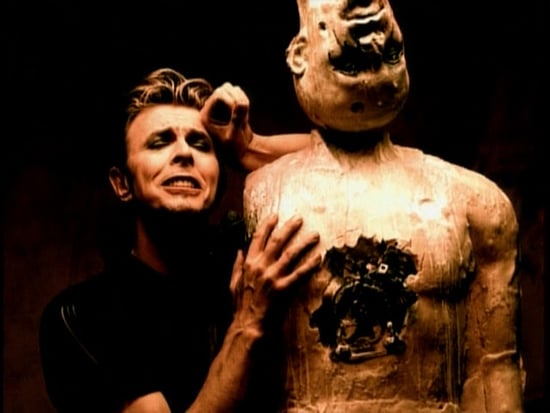

Nonetheless, the essay was a portent of Bowie’s next phase, for better and worse. Always a closet intellectual and never having abandoned an interest in the visual arts, Bowie started to build quite a resume as a music and art critic, and after decades of dabbling started seriously exhibiting his own work, often with the controversial neo-pop figures, such as notorious dissection artist Damien Hirst, who were then storming England. In 1995 Bowie decided to bridge these sophisticated pursuits with his pop-music practice, and enlisted Brian Eno for the reunion album 1. Outside. The duo’s preparation became the stuff of instant public-relations legend. They dressed their recording studio as an art atelier, and visited a famed collection of mental patients’ paintings for inspiration. Eno encouraged the musicians to paint and sculpt as a catalyst to creativity, and instead of describing how he wanted them to play, wrote them character sketches to get into. Unfortunately, the album’s process proved more interesting than its outcome, a slapdash paste-up of shopworn avant-garde clichés which seemed as contrived to restore Bowie’s highbrow credibility as Let’s Dance had been to establish his commercial clout.

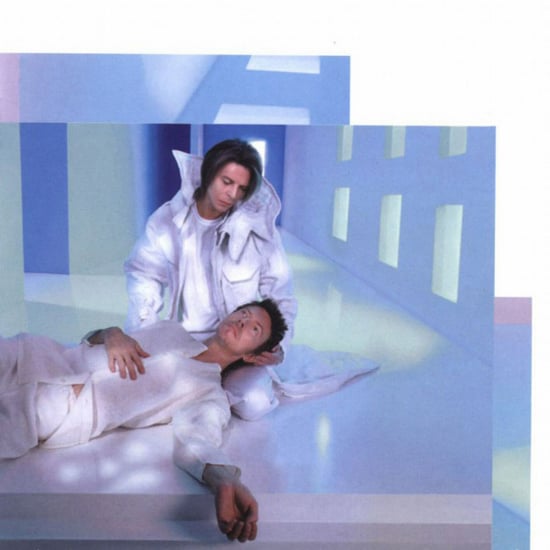

Calculated or not, 1. Outside reestablished the desired respect from press and public. This sparked a renaissance in Bowie’s creative confidence, freeing him to follow up with two of the most inspired and well-received albums in his history. Though they couldn’t have been more different from each other, each expressed Bowie’s reflections on the new technology whose promises were the pervasive talk of the late ’90s. Earthling (1997), a crowning achievement of edgy yet infectious pop, was a summation of the electronica style of manic computer-manipulated beats, muzak-like ambient vistas, sampled found-sound collage and ghostly vocals, which had many roots in the Bowie/Eno Berlin Trilogy. As he’d done with glam on Ziggy Stardust, Bowie took a vanguard style and made it his own. Sensing a pendulum swing from the high-tech to the humanistic, ‘hours…’ (1999) was an ingenious reinvention of the confessional singer-songwriter genre for the digital age, setting chilly computerized textures alongside a dazzling array of influences from the opposite end of the musical spectrum in both style and era, including coffeehouse acoustic balladry, crunching heavy metal, and the quaint jingles of Bowie’s own mid-’60s apprenticeship. (One of his most personal albums, ‘hours…’ was in fact repurposed from a videogame Bowie had scored, and one of the lyric rewrites was done not by him but by a fan who had submitted it in an online contest; not the first time — the Station to Station album, the Sound + Vision tour — when what would seem expediency or gimmickry for another artist acted as an improvisational catalyst to creativity for Bowie.)

Bowie was not just engaging the new technology as subject matter. He became the first major-label artist to offer a single exclusively on the Internet (“Telling Lies,” 1996). He went on to found the first artist-run Internet Service Provider, Bowienet, which supplied both the typical services and exclusive access to special concerts, artist chats and downloadable sound files from his impressive trove of rare and unreleased material. In a characteristic blur between art and commerce, this service generously established an “online community” of aficionados while cornering the market on obscure Bowie material, which disappeared from elsewhere on the Web with uncommon thoroughness (though with the pipeline siphoned beyond reclaiming in the 2010s, much of that has seeped back onto YouTube, with the artist’s presumed blessing or at least characteristically shrewd acceptance). Another site, Bowieart, presented emerging visual artists and sold their work without the confiscatory commissions of average galleries. (Bowie dedicated himself to long-term patronage of the arts, in England co-founding an art-book company, 21 Publishing, and in the U.S. helping underwrite the controversial Brooklyn Museum exhibit “Sensation.”) More on the commerce side of the equation, Bowie also became the first rock star to trade himself on the stock market, floating bonds against the royalties on his back catalogue, which was perennially re-released to increasing sales and licensed to the highest-bidding TV commercial producers. There was even a Bowie-branded online bank.

The public welcomed his new work, caught up with his earlier material, and accepted his financial ventures as his due. In the ’80s Bowie had achieved transient acceptance by compromising with the mainstream; by the 2000s he had achieved lasting legitimacy as his outsider sensibility overtook the mainstream. The gay aesthetic and avant-garde referents he had championed were now common currency, and the independent artistic vision he’d pursued now had an infrastructure of niche media to serve its actually sizable audiences. Bowie had reached the rare pop-cultural status of being an elder statesmen still free to experiment and expected to surprise.

Tomorrow in Part 7: 2010s, a spacetime odyssey

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: Theater Reviews: The Honeycomb Trilogy, Love Und Greed, Nord Hausen Fly Robot, The Oracle | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Full Fathom Five,” an analysis of a panel from Jack Kirby’s New Gods | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The 10-part review series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam McGovern’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE