Bowieology (4)

By:

January 11, 2015

Fourth post in a series of seven, surveying David Bowie’s cultural contributions as he enters his second 50 years of acceptance and transgression.

In Berlin, Bowie collaborated on two historic albums with punk precursor Iggy Pop, The Idiot and Lust for Life (both 1977). (Bowie’s friendship with Pop went back to his co-producing of Pop’s legendary album Raw Power in 1973, around the same time that Bowie and Ronson were also revitalizing the careers of underground poet laureate Lou Reed [by producing Reed’s breakthrough Transformer in 1972] and glam superband Mott the Hoople [by doing the same for their career-defining All the Young Dudes, also in 1972].) For his own albums, Bowie teamed with conceptual-rock trailblazer Brian Eno on what came to be famous as the “Berlin Trilogy.”

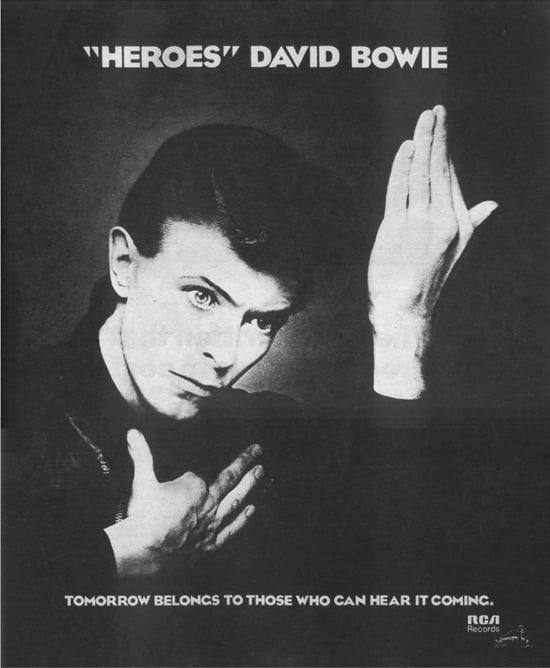

A pioneer of the synthesizer, Eno was best known (though at the time scarcely appreciated) for sweeping, atmospheric instrumentals which set the blueprint for both “new age” mood music and the “ambient” genre of ’90s electronica. He also specialized in fragmentary, eccentric pop vignettes which reflected the shortening attention spans of a media-saturated era. Bowie adopted both forms for Low and “Heroes” (each 1977), giving many listeners and future musicians their first exposure to Eno’s innovations, and adding intermittent, disjointed lyrics which would influence the chic alienation of later “new wave” acts. No mainstream artist since the Beatles had stretched the boundaries of what could be admissible as “rock” this far, and Bowie lost sales while gaining reverence from fans for his commercial sacrifice. Always thriving on contrasts and relishing the unpredictable, Bowie broke his exile with two world tours, one as Pop’s unbilled keyboard player and the other as a headliner, alternating his challenging new music with revived Ziggy numbers which in context seemed just as audacious.

Returning to the studio and Eno, Bowie completed Lodger (1979), which incorporated the polyglot of ethnic influences hinted at on “Heroes” into a series of quirky pop tunes with African, Turkish, Jamaican, and other influences in a presentiment of the “world music” boom of the 2000s. By the late ’70s the music-video market Bowie had helped pioneer was an influential enough force that Lodger’s homoerotic promo clips were able to significantly impair the album’s commercial prospects. But Bowie had become most concerned with art-for-art’s-sake credibility, and would next jump to yet another medium to secure his air of high seriousness.

In 1980 Bowie played the lead role in the demanding Broadway play The Elephant Man, to unanimous critical approval. Maintaining his presence and preserving his options in both highbrow and vernacular arenas, Bowie simultaneously released Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), a masterful album of cacophonous but catchy post-punk that sold surprisingly well and set a standard for the following decade of alternative music. These two accomplishments formed a finale for this phase of Bowie’s career. Said to be distraught over the murder of his friend John Lennon and determined to take a larger role in the upbringing of his young son (Zowie, now known as filmmaker Duncan Jones, the product of an early-’70s marriage to American model Angela Barnett), Bowie retreated from the spotlight for three years. He would step back into it briefly in 1981 and ’82 for a handful of rock and high-art place-holders — on the one hand, the theme song to the film Cat People and the hit duet with Queen, “Under Pressure”; on the other, a starring role in the BBC production of Bertolt Brecht’s first play, Baal (never aired in the U.S.), the grim tale of an amoral wartime troubadour, with a soundtrack EP which featured some of the most haunting vocal performances of Bowie’s career. But for the most part the artist was off the scene, and when he returned, it would be in his least recognizable guise yet.

1983’s Let’s Dance commenced a six-year period that was Bowie’s most commercially successful and is now his least favorite, though it clearly seemed like a good idea to him at the time. Recanting his sexual and musical experimentation and producing an album of unstoppably salable dance-pop, Bowie personified Reagan-era conformity in what might have been his most biting character if not for the uneasy feeling that this time he wasn’t kidding. Let’s Dance won Bowie a fleeting mass following while dismaying former fans, but in fact Bowie’s interest and creativity had merely concentrated elsewhere, in the performing arts. The videos for the title track and “China Girl” maintained his knack for controversy and pop-culture critique. As the “Australian Invasion” found white acts from Down Under overrunning the same pop charts Bowie was climbing, the scenario for “Let’s Dance” depicted a young Aboriginal couple’s rejection by and of white Australian society, in a vignette Bowie described, at the height of Cold War tensions, as “Russian social realism.” The “China Girl” clip ran through a recriminating fantasia of stereotypes as imagined by the song’s racist narrator, and ended in a widely-censored beach lovemaking scene, which exposed the singer’s bare backside long before even this much male nudity became acceptable. In the same year, Bowie starred in The Hunger and Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, the former a disturbing bohemian vampire movie and the latter a provocative account of life in a WWII Japanese prison camp by a Japanese director. Only fate stood between Bowie and two further footholds in prestigious precincts outside of pop: he was scheduled to play Abraham Lincoln in a staging of avant-garde theater impresario Robert Wilson’s The Civil WarS at the 1984 Olympics but the performance was called off, and he sought to obtain the rights to (and presumably re-score) Fritz Lang’s classic silent science fiction film Metropolis but was outbid by his “Cat People” collaborator Giorgio Moroder.

Clearly Bowie hadn’t completely lost his lofty leanings, and was fretting to interviewers about the commercial pandering of Let’s Dance as early as 1984, when he released the sonically lush but emotionally remote Tonight. Unfortunately any ambitions he might have had to rehabilitate himself musically were deferred, as the proportion of new material to covers and remakes on Tonight dipped to under half (from Let’s Dance’s ratio of just over). Yet once again, Bowie excelled not only commercially but creatively in other media, with a short film shot to promote the hit single “Blue Jean.” An antidote to the vacuous videos and a parody of the pop trends then current, the film featured Bowie in a dual role as a clueless music consumer and his idol, Screaming Lord Byron, a farcical though compelling composite of Bowie’s Ziggy phase and the new-wavers and new-romantics who had cloned his creations more lucratively than he. Expanding the possibilities of its medium and holding a mirror to the excesses of its industry — and its own star — while presenting one of Bowie’s most memorable characters, the film was 15 minutes of not only fame but redemption.

Tomorrow in Part 5: All the world is staged

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: Theater Reviews: The Honeycomb Trilogy, Love Und Greed, Nord Hausen Fly Robot, The Oracle | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Full Fathom Five,” an analysis of a panel from Jack Kirby’s New Gods | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The 10-part review series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam McGovern’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE