The Unconquerable (22)

By:

November 27, 2014

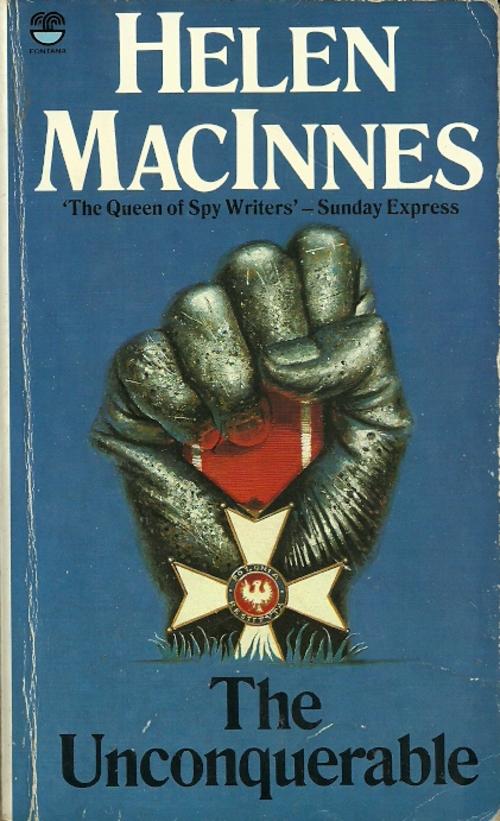

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Casimir may have wondered why his bedtime followed supper so quickly that night, why Madame Aleksander and Sheila sat up late writing on magazine margins and burning discarded pages in the rusty stove in the kitchen, why they rose so early next morning and worked so silently about the flat, why he was given so many little tasks to do that he too had no time to talk. But, with the unexpected patience of the very young who will trust infinitely if only their affection is answered, he obeyed all Madame Aleksander’s suggestions, because he saw that it pleased her so much. He felt happy too, because she seemed to be quite better to-day. Her voice and all her movements weren’t ill any more. He whistled as he cut out muslin ‘window-panes’ and tacked them into place; the ply-boards, he had decided, were to be used as shutters for bitter weather and night-time.

Sheila, as usual, wanted the dog to be washed. Madame Aleksander had said she was going to see her brother and then to visit the Kommandatur. Sheila said she would have to go out, too, but she thought Volterscot needed one more bath before the weather got too cold.

“But isn’t that his natural colour?” Casimir asked.

“Not yet. He should be white. He will feel much better if he is really what he should be.”

Casimir rose, still reluctant to leave the hinge he was trying to invent to make a neat shutter. “All right, Sheila. If that makes him feel really better. But you are awful fussy about baths. Come on, Volterscot!”

“We’ll all meet here again this afternoon,” Madame Aleksander called after the boy and his dog. “Take care, Casimir.”

To Sheila she said, “I am going out now. Are you coming?”

“Not at the moment. I have some sewing to do.”

The two women exchanged smiles as if each knew what the other was thinking: how stilted and self-conscious the simplest phrases became if one was not sure of privacy. And then Madame Aleksander had also gone, and Sheila was left alone to put her plans into action. First she must get in touch with Hofmeyer. Casimir had to be hidden before the Germans arrested him. If she ’phoned that very private number she could leave a message to be given to Hofmeyer when he visited that address.

Yet, somehow, she wanted to reach Hofmeyer without delay. The problem about Casimir was urgent. Perhaps it was too late even now. Suddenly she thought of a way to telephone Hofmeyer at his office without arousing suspicion. She arranged her thoughts into a line of conversation, and the more she examined what she would say, the surer she was that this would be not only the quickest but the safest method. It was only natural that she should want some respectable clothes and a decent meal. Anna Braun would demand those things. And Sheila Matthews would be a more efficient person if she felt less like something the cat had dragged in. She looked like a beggar; she was beginning to feel like one. She urged her courage with these thoughts and called the number 4-6636 before she could change her mind. She listened to the ’phone’s distant summons and looked at her disreputable coat and her cracked shoes. Never again would she wonder why soldiers and sailors should keep their uniforms smart. Never again would she smile at button-polishing or deck-scrubbing.

Hofmeyer sounded abrupt and busy. Her initial confidence ebbed slightly. He was probably going to be furious with her. Her first question about any further instructions sounded painfully weak. But perhaps it was that hesitancy which caught his attention. “What else?” he demanded.

How pleasant and easy it would be if this were a normal world and she could say “Casimir’s in trouble. Please help him.” Instead, she said as Anna Braun might have said, “I thought I’d like a decent meal. I’m cold and depressed. What restaurants would you like me to use?”

“So that’s it. How much money have you?”

“Little, and it belongs to the housekeeping. I wondered if I might have an advance on salary? I need some clothes, too. I lost all my luggage in one of the September fires.”

“Call at this office and collect some money, then. You can eat at the Europejski Restaurant.”

“You mean I can go there alone?” Sheila hoped that her inflexion on that sentence would be enough to make Hofmeyer realize she wanted to have one of those little walks with him.

But he ignored the question. “You can choose some clothes from the bedroom wardrobes when you call here. You should have taken some yesterday, as I suggested; the best of them are gone now.” He turned away from the ’phone to talk quickly to some one else in the room.

“These clothes may not fit me,” Sheila said. She would rather wear her present rags than loot some unfortunate girl’s….

“I see,” Hofmeyer said abruptly. She hoped desperately that his tone and manner were for the benefit of that some one else in the room. He was talking to the unknown man once more.

“Are you there, Fräulein Braun? I am sending round one of our young men who will take you to one of the larger shops, together with entry pass and credit check. This is a great nuisance, Fräulein Braun.”

“I am sorry, Herr Hofmeyer,” She said meekly. She was beginning to wilt like a child under its parent’s disapproval.

“My man will collect you in half an hour. His name is Hefner. He may seem Polish, but you can rely on him. He is a true German. Are you alone at the flat? All the better.”

Well, Sheila thought as she replaced the receiver on its hook, she had tried to arrange a meeting, and all she got was a shopping tour. She began to analyse the conversation once more. No, she had made no slips. She couldn’t have risked anything more obvious. Surely Mr Hofmeyer didn’t really think that she had troubled him only because of a meal and some clothes?

After that she worried about Mr Hefner until he arrived punctually. Mr Hofmeyer had warned her, at least. He may seem Polish…. Don’t, Anna Braun, forget your catechism.

Anna Braun answered the polite knocking on the outside door. The man was in civilian clothes. He was thin, blond, and blue-eyed. With his broad brow, high cheek-bones, wide mouth, straight nose, he might very well have been a Pole. His bow and greeting were also Polish. He had an excellent accent. He had obviously been given a description of her, for his identification card was already showing in the palm of his hand. Sheila slid hers quickly out of her bag. I should laugh, she thought, I should laugh if the price of a smile wasn’t a bullet against a stone wall. A sense of humour was costly nowadays.

“Miss Sheila Matthews?” he asked, and listened intently for any sound of life in the flat. His excuse for this visit was on the tip of his quick tongue.

“There is no one here.”

He looked relieved, bowed again, said “Hefner!” as he bowed. “Are you ready, Fräulein Braun?”

“Yes.” Preparations to go out certainly became very simple when you had to wear your coat indoors.

In the bright light of the street he frowned at her coat and her shoes. He didn’t seem to enjoy walking beside her. He hurried her into the car which he had left innocently round the corner. Sheila’s smile disconcerted him. He was probably ashamed of being ashamed at accompanying a poorly clad German. He certainly had his own ideas of the comforts a German should have even when imitating a bombed-out Pole. Anyway, he didn’t speak during the short ride in the car, and Sheila had decided to ask no questions and to offer no conversation. She wondered what shop could be open to sell clothes. All the buying she had seen recently had taken place from hawkers’ trays. She marvelled that the route into town, which she now knew so well and had always considered rather long, should in reality be so short.

She concealed her surprise when the car stopped in an alley, at the goods’ entrance to one of the large shops which yesterday she had noticed was among those boarded-up. It still appeared to be in that category, for the noise of workmen’s hammers clattered spasmodically into the street. But at this side-entrance there was a guard. As soon as Hefner had produced a ticket of the proper shape and colour the guard swung the heavy door open, they entered quickly, the door closed firmly behind them. Aladdin in his precious cave could not have been more blinded than Sheila.

The strangeness of the bright electric lights at first dazzled her, and then as her eyes became accustomed to the glare she saw that her first unbelievable impressions were really true. Behind the boarded windows the long counters were heaped with merchandise. Perplexed shop assistants were helping an array of uniforms to make their purchases. Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, Gestapo uniforms jostled each other and the few Germans in civilian clothes; all madly buying; all talking at once; all using elbows and stretching hands freely. Yards of cloth, underwear, perfume, blouses, hats, dresses — it didn’t matter what they bought as long as they found something. The only impulse was to buy and buy; the urge to spend, to acquire was on. There was plenty of occupation money. With this arrangement even the most expensive articles were practically given away free. Why bother with the farce of worthless notes at all? Sheila thought bitterly. She noticed with some embarrassment that there were only nine women in sight (apart from the Volksdeutschen behind the counter and these were definitely camp-followers: streamlined, chromium-plated camp-followers with elegant hair and shoes and voluptuous fur jackets, but still camp-followers, who would share in the loot in return for favours rendered. Sheila remembered a phrase of Steve’s. On the receiving end: … we’ve been on the receiving end. And now, here she was on the opposite side. She had seen what it was like to be defeated by the Germans; now she was seeing the other side of the picture. Herr Hefner didn’t seem to notice what little zest she had for choosing new clothes.

Perhaps that was because he himself seemed to enjoy arranging what she should buy. “Something which would be smart enough for a secretary and yet not too outstanding for your Polish friends to live with,” was his judgment.

“Yes,” Sheila said, looking at his extremely expensive suit and delicate tie. Herr Hefner had his own rules for himself, it would seem. The only thing that surprised him was her moderation. He looked at the heavy brown coat, the grey wool suit, the brown wool sweater, the simple grey felt, the brown shoes and warm gloves.

“Are you sure that’s all?” he asked with a puzzled frown.

“On my first month’s salary, yes. Secretaries don’t earn so much, you know. Besides, I have some other things to buy.”

“Oh, yes, of course,” Herr Hefner agreed with a smile, looking in the direction of the underwear department. “Over here, I think.”

Sheila didn’t move. “Later,” she said sweetly. “But first I must buy something for the people with whom I am living.”

He frowned again. “Is that necessary, Fräulein Braun?”

“They would accept my new prosperity more naturally if I did buy them something.” She saw by his face that she had won her point.

“Not in this department, then,” he said. “These clothes are wool. We’ll find cheaper things.”

Sheila concealed her disappointment with an effort. When you were hungry you always felt twice as thwarted, it seemed. She followed him to the other side of the shop where fewer officers and more private soldiers were selecting clothes for those at home. She chose the warmest black dress she could find for Madame Aleksander and a thick sweater for Casimir. She tried to buy a heavy scarf for each of them, too, but Herr Hefner would have none of that. “You’ve bought more than enough for them,” he said. “This is unusual, Fräulein Braun.” He still looked undecided, as if he were calculating what Hofmeyer would have to say to such unnecessary expense.

“They are so cheap,” Sheila said, and left the department before he thought better of his acquiescence. She led the way through a crowd of soldiers buying silk and lace underwear. Hefner was beside her, much to her surprise. “You’ll need some of this, I suppose,” he said, watching a tall, lean soldier holding up a peach satin night-dress in front of him with a critical eye.

Sheila said, “I shall have a cold winter if I live with the Poles. I’ll need warmer things than that.”

As she chose the heavier, plainer silks (she was not Spartan enough to choose the dull and depressing cottons) Herr Hefner was saying, “I admire your restraint. I suppose it is necessary.”

“I must live my job, after all, Herr Hefner,” she replied, and that satisfied him completely. “Now I’m going to wear some of these things, and the rest can be wrapped up.” She headed determinedly for a possible fitting-room, evading two Luftwaffe men who were measuring silk stockings along their own legs. Herr Hefner hovered outside the cubicle. It was an extraordinary thing, Sheila thought as she changed her old clothes for new, that no one in this building had looked round him and burst out laughing. She had never seen so many little groups of people all so intent on their own little purposes, and yet all coming under one large theme: loot. Breughel, she decided, could have filled one of his enormous canvases with them. He would have enjoyed their petty preoccupations and painted them into one sweeping satire. Here in this corner would be the two airmen measuring stockings. Here the soldier with the night-dress in front of him. Here the three Gestapo men stretching girdles to see if the rubber was good. (They ought to know a lot about rubber with their experience in clubs.) Here the two officers each with an armful of perfume bottles and bath salts. Here the lacquered blonde with her hand held under the lace and ninon bed-jacket. And behind the hundred little groups would be the ragged outline of a murdered city, a pyramid of bones, and a mad woman wandering.

Herr Hefner looked at her critically when she at last left the fitting-room. His impatience vanished. He looked surprised, pleased. “Good,” he said.

“I think you chose the right things.” That pleased him still more. And she added one more drop to his cup of self-esteem by saying, “I must tell Herr Hofmeyer how very efficient you have been.”

He lost all the stiffness he had shown in the car. He was now far from ashamed at being seen with her. In his relief he became effusive.

“Now, what about a cocktail? And you needed a good meal, too. I remember that. Why don’t you have an early lunch with me now at the Europejski? The best people go there. And it has a corner left for Poles, so we shall be safe if any of our Polish friends see us enter the restaurant.”

“Splendid,” Sheila said, and hoped she was enthusiastic. “What about letting Mr Hofmeyer know where we are going, in case something urgent turns up for us to do?”

“Good. I’ll ’phone, while you collect the packages.”

Sheila bought two woollen scarves in the more expensive department. They were much better, softer, warmer, than those she had first tried to buy. They were neatly included in her parcel by the time Hefner had returned from the telephone booth. He arrived in time to watch the last knot of string being securely tied, and remarked pleasantly, “They take a long time to get packages together these days. But I expect many of these girls are new to this job.”

Sheila agreed with a bright smile. The two hidden scarves were her own small triumph. She would have smiled at anything Herr Hefner said at this moment.

They lunched well, except that Sheila found she couldn’t eat so much after all. She spent the latter half of the meal in sipping a glass of weak tea, avoiding the sight of Herr Hefner’s excellent appetite as tactfully as she could. She found herself longing for the cold draughts of Steve’s rooms. The warmth and noise of the restaurant, instead of being as exciting as she had imagined, only made her feel still more sick. Remember in future, she told herself, whenever you think you are missing bright lights and laughing voices and interesting food, that these things aren’t the fun they used to be. It was all relative: if you weren’t free a palace for a home would be less bearable than a poor cottage where friends could be together. Better a dinner of herbs where love is than a stalled ox and hatred therewith.

Mr Hefner did most of the talking, which consisted mostly of questions. Sheila had to pretend to be quite unguarded, while her mind quickly analysed each harmless remark to find how deep the bog was, before she could venture one foot in it. The only way to cross safely was to scatter some conversational bracken leaves over the treacherous surface, and in this way she gave the appearance of having evaded not one question without having given any particular answer. Hefner wanted the details of the Warsaw siege (he had just arrived from Danzig), and the only difficulty there was that she had to remember she was supposed to have enjoyed every minute of it. Hefner talked about Munich, where he had once spent a year at the Geopolitical School. That was answered by lots of chatter about Aunt Thelma, about pleasant days at Nymphenburg, with its charming Dutch kitchen in the hunting lodge where Amalie and her ladies had liked to cook for the King and his court, about the Dachau Museum with its walled garden and thin brown pears and its view of the Bavarian Alps and the Zugspitze.

“Dachau…” mused Hefner. “That’s become a very interesting place in the last few years. But, of course, it’s been some time since you were there, hasn’t it? Why didn’t you ever go back?”

“Money,” she explained, with a sad smile. “And when I had saved enough for a trip to the Continent my aunt was in Switzerland and Mr Hofmeyer met me. He persuaded me to go back to London, to continue to wait. He had plans for me.”

She watched Hefner, but she must have said approximately the right things, for the clever look in his eyes was gone, and he was genuinely sympathetic. He became quite sentimental.

“The lives of our German brothers and sisters who must work in foreign countries are indeed sad,” he said.

“But necessary.”

“Of course, very necessary. We have a second army in them. Their rewards will be high. Don’t worry, Fräulein Braun. You will enjoy the benefits fully some day. Only have patience for a little longer.”

“It won’t be long now?”

“Absolutely not. Another six months at the most, if peace isn’t negotiated before then. Our Führer has promised that. He is never wrong.”

What, never? Well, hardly ever. Sheila thought; and watched with relief and rising hope the white head and lined face which had just entered the restaurant. Mr Hofmeyer had not misinterpreted her telephone message, after all. He walked towards them as if by accident, as if he were merely looking for a table.

Quietly he motioned Hefner to sit again and pulled over a vacant chair from the next table.

He looked at Sheila and said, “Well, you didn’t waste your time, I see.”

“That was due to Herr Hefner. He was very helpful and very kind.”

Hefner beamed. “It was a pleasure, Fräulein Braun.”

Hofmeyer ordered an elaborate meal and said casually to Hefner, “Don’t wait for me. Dittmar said he wanted to see you at his office.”

Hefner rose abruptly, his face already obedient at the name of Dittmar. He said to Sheila, “I hope we meet again soon. You like dancing?”

“Yes — when I have time.”

“Good. I’ll ’phone you if I may?” He bowed to each of them in turn and hurried away.

In a low voice Sheila said, “I thought he was your young man, not Dittmar’s.”

Hofmeyer was very absorbed in measuring salt and pepper. “He serves us both. Dittmar was in conference with me this morning when you ’phoned. It was he who suggested Hefner should accompany you this morning.” His voice dropped. “I’ve been worried ever since. Hefner is a very percipient young man. But I see you did well. I could tell that from his manner.”

He ate with remarkable speed. “I see that I’ve been left with the bill to pay, however,” he said dryly, as he called for the waiter. “Hefner will be a rich man some day.” Then he looked at the large package which Sheila was pulling out from underneath the table. “We can’t walk far with that,” he said.

“But I’d like a short walk. I need fresh air. It is too hot in here.”

Hofmeyer paused in counting his change. “So?” he said slowly. He lifted the package and carried it towards the street without any more delay.

“Why are you smiling?” he asked, as he turned in the direction of his office.

“Herr Hefner was too dignified to carry that parcel. He’s quite the most graceful snob I have ever met.”

“In the restaurant you were very serious for a moment. I knew you must want to see me when you ’phoned. But is it as bad as the way you looked when you said you needed a walk?”

She told him quickly about Casimir. “And I am sure there’s a dictaphone. There were too many workmen pottering about the flat yesterday with no obvious results to show for their labours. Where would that dictaphone be?”

“Anywhere. It’s a small thing. Probably linked up with the telephone.”

“Then our words would be heard as soon as they are spoken?”

“Yes. All telephones are operated by Germans now.”

“Then Casimir could be arrested at any moment?”

“When we think it’s worth our while to arrest him. We’ve plenty of more important people to arrest. He will be on the black list for treatment as soon as we have the time. That may be to-morrow or next week. To-day we are busy.” He paused and then said still more gravely, “Edward Korytowski was arrested at dawn this morning.”

Sheila turned white. She was going to be sick. She halted and leaned for a moment against a bullet-scarred doorway. The attack of nausea passed.

“For what reason?” For the meeting at his apartment? her eyes asked anxiously.

“Professors are being arrested. That’s the only reason.”

“What will happen to him? To the others? Most of them were too old for military service.”

“He is being sent to Dachau.” A very interesting place, Hefner had said. In spite of the mid-day sun striking through her new wool clothes, Sheila shivered. The pavement under her feet lost its even surface for the next few steps. Uncle Edward. Dachau.

“Polish culture must be destroyed,” Hofmeyer said in a hard voice. “The orders were issued yesterday. No Polish universities or colleges or high schools. No Polish libraries, newspapers, priests, law courts, or radio. The great silence has begun.”

Sheila couldn’t speak. She stared unseeing at the buildings in front of her.

“As for Casimir, either Department Fourteen will help him to leave Warsaw at once, or perhaps we could find some use for him with Number Thirty-one.”

Sheila forced herself to pay attention. Those who still could be saved must be thought of first. “Thirty-one,” she said. Casimir would rather be with those who helped the guerrillas than be sent out of Poland. “He’s so alone,” she added.

“As soon as you get back to the flat, send him away at once. To Warecka Street, Number 15. They will hide him until we can make arrangements for him. He seems a brave boy, this Casimir.”

Sheila nodded. “Worth helping,” she said. When Poland was free again she would need all her Casimirs. “Shall we ever see him again?” she asked.

“No. And better keep the dog with you. Don’t let it follow him. It could give him away. You understand?”

She nodded wearily.

“We shall soon be at the office. It was better not to take a long walk to-day. I am bringing you back here to discuss the problem of Korytów, so that this journey here together will seem natural.”

Something in his tone aroused her. “Is Dittmar suspicious?” she asked quickly.

“He trusts nobody. There are too many gambling for power to let us be generous and trustful with each other. Don’t worry. The dictaphone and tapped ’phones are merely part of the Nazi methods. They like blackmail. They don’t expect State secrets; they are content with an ill-chosen friendship or a hidden love affair or an unadvised opinion to give them a hold over their fellow spies. Dittmar thinks he is clever; he watches me because I’m a serious rival; he watches you because some day he may want to use you against me. That’s all. Besides, I watch Herr Dittmar just as carefully.” Hofmeyer smiled as he transferred the weight of the parcel from one arm to another. I too have enough influence to have dictaphones installed, he seemed to say.

“I still think he doesn’t accept me,” Sheila said. “He cannot forgive me the fact that I escaped and Elzbieta didn’t. He’s possessive. Her death was an injury directed at him.”

“He accepts you slightly more since Captain Streit approved of you yesterday morning.”

Sheila looked sharply at Hofmeyer. What riddle was this?

“Streit is Gestapo chief for our district. He recommended your information on Gustav Schlott as a future helper of the Poles. Don’t look so distressed. I assure you Schlott was too warm-hearted and simple; he had already talked too much. He would have been caught red-handed helping the Poles. Then he would not have been evicted. In fact, we saved his life. I forwarded your report on him two days ago. Yesterday action was taken.”

“What a miserable kind of person you’ve made me out to be!” Sheila said resentfully.

“But what an excellent Nazi, Fräulein Braun. And, after all, I have got to justify your existence here from time to time.”

Neither of them spoke as they approached the large house where Hofmeyer had^ his suite. They kept their silence until they were inside Hofmeyer’s own private office.

“I brought you here,” he said crisply as he rubbed circulation back into his fingers, “because a decision about Korytów has been reached. It seems that the village has been giving us trouble. A punitive expedition is to be sent against it. An example will be made of the village, and certainly the Aleksander woman will not receive permission to travel there. I, at the moment, am too busy to be able to find a solution for you. So are the other departments. For the victory parade into the city takes place on the sixth of October; that is the day after to-morrow. The Avenue Ujazdowskaja has at last been made fit for the parade, and our Führer will himself be present. Naturally, we are busy finding prominent hostages and arresting potential troublemakers. You can see how the problem of Korytów is now one for you alone.”

He watched the amazement on her face and continued, “I have done all I can at the moment. Here are the necessary permits which will allow you to make the journey. If you do so it will, of course, be on your own judgment and risk. Herr Ditt — the other department which I hoped would facilitate your journey refuses to help at this moment. They consider the Aleksander woman and her children are of no importance.”

Sheila’s horror over the fate of Korytów gave way to dismay as she realized that, if Dittmar’s policy (for that slip of Hofmeyer’s tongue as he referred to the department which had been so unco-operative was no accident) meant no Aleksanders, then that meant, in turn, no Sheila Matthews. As Anna Braun she would be given some real German work to do. Dittmar might even try to have her transferred to his department.

A telephone call interrupted Hofmeyer’s account of how she might attempt the journey to Korytów if she decided to make it. Sheila sat tensely while he answered it. Surely Hofmeyer realized that this was Dittmar’s thin end of the wedge to ease her out of the Aleksander-Matthews relationship? Surely — and then, looking at the number of permits, clipped together, which Hofmeyer had pushed across the desk to her as he reached for the telephone, she knew that he fully realized that. He wanted her to go to Korytów and keep the Aleksanders together, together with her own excuse of being Sheila Matthews. He knew, too, that any other solution would lead her into grave complications, perhaps himself and Olszak into danger. He knew. Otherwise he wouldn’t have taken the trouble to get these permits for her. If his permission now seemed grudging it was only because he was manoeuvring against a department or combination of departments which were powerful. She examined the permits; they allowed her considerable freedom of movement. She couldn’t help thinking what an involved way of wasting time and energy all these pieces of paper represented: this was carrying German method to a ludicrous extreme. She thought of Uncle Matthews for the first time in days; how he used to grumble over the inanities of income tax returns. He ought to see the complexities of German rule. And then she realized that Uncle Matthews, attached to some branch of British Intelligence as he must be, would probably see samples of all these permits. And Department Fifteen of Olszak’s organization was no doubt making excellent copies of them at this very minute. Department Fifteen. Stanislaw Aleksander. There was her plan. Her main problem was solved. Once she could get the Aleksander children and their mother reunited Stanislaw could attend to their papers and credentials. She would get them safely out of Poland yet. The feeling that she must go to Korytów was strengthened. And she must go at once. If only Dittmar’s department had been helpful she could have made the journey so quickly, so easily. With an official car she would have been there in less than an hour. She would have been in time to warn Korytów. She stuffed the papers into her handbag, wondered how quickly she could make the journey on her own initiative, worrying if she would reach the village in time, wishing Hofmeyer would stop ’phoning and let her leave.

He ended his series of abrupt “Ja!” and “Jawohl!” He replaced the receiver, looking at her with eyes suddenly worried, with lips tightly closed. “Herr Dittmar would like to see you. He has sent Hefner round here to collect you. He wants you to identify Kordus.”

“Kordus?”

“Yes, they have a body over at the Gestapo headquarters which they believe to be Kordus. The man would not admit anything before he died.”

“I am to go to Gestapo headquarters?” The look on her face awakened Hofmeyer’s pity.

He stopped looking worried and said lightly, as if to cure her of this sudden stage-fright, “Yes. They are in the former Ministry of Education building in Szucha Aleja. That isn’t so far from Frascati where you are living. Consider it just a break on your journey home with your new autumn clothes.”

Sheila smiled weakly. “That parcel is becoming a nuisance,” she said. “I think I’ll ask Herr Hefner to take me to Frascati Gardens first. That’s on the way, anyway.” And then I can at least tell Casimir to leave, she thought. Perhaps she herself would never come out of the Gestapo building once it swallowed her up.

Hofmeyer was obviously relieved at the casualness of her voice, but he noticed the tense neck, the hands held too stiffly. “So we’ve got Kordus,” he said. But he shook his head warningly. Don’t believe it, his eyes said, don’t believe it.

“Now I have some work to do, Fräulein Braun. While you wait for Hefner here are some copies of the newest decrees and regulations. They will show you how we intend to treat the Poles.” He handed her a pile of printed sheets with impressive heads. On a slip of paper attached to the top page he scribbled: “Careful. Fake.”

She left him, with a newly lighted cigarette in his mouth and a piece of flaming paper in his hand. His eyes were on her as she closed the door. He gave an encouraging smile. That was the last time she ever saw Hofmeyer.

Herr Hefner set himself out to be fascinating. He talked gaily all the way to Frascati Gardens. Sheila had an uncomfortable doubt as to whether all this charm was the result of genuine liking for her, or whether he was only following special orders. He was extremely obliging about halting the car round the corner from Steve’s flat and letting her carry the heavy parcel towards the doorway.

“Only a few minutes!” Sheila called over her shoulder to the waiting car. As her neat new heels sounded smartly on the pavement she was already planning how to use every available second.

She called out half-way up the staircase so that they would know she was coming. Madame Aleksander was blowing out a match. In a soup bowl, the pieces of paper on which she and Casimir had been writing remained unburnt. She was smiling, partly in welcome, partly in relief,

“We have been playing that funny game you taught the children this summer,” Madame Aleksander said. “What is its name?”

“Consequences,” Sheila answered in a very normal voice, but her fingers had become all thumbs, and she could hardly open the parcel. She looked sideways at the pieces of paper which Casimir and Madame Aleksander were now smoothing out to show her. So Madame Aleksander had been forced to tell him something about the dictaphone to silence his otherwise irrepressible remarks. Now he was excited. Like all children, he loved a secret, especially one so strange and mysterious. His blue eyes were shining, and there was a flush on his pale cheeks. This was a game which he enjoyed, and perhaps even understood better than the two women.

Madame Aleksander had noticed Sheila’s clothes. “But how nice you look,” she said delightedly.

“I asked Herr Hofmeyer for an advance in my salary.” Sheila pulled out the dress for Madame Aleksander, the sweater for Casimir and the two scarves. “For you,” she said, and watched Madame Aleksander’s surprise give way to pleasure.

“I was feeling cold,” Casimir admitted, grinning happily because he had not been forgotten. Sheila had lifted his pencil and piece of paper. To Casimir, his head emerging with ruffled fair hair from the neck of the new sweater, she made a sign of silence. She began to write:

“Casimir! The Gestapo already know of the torn posters. You must leave at once. Friends wait for you at Warecka 15. Keep silent.”

The boy looked wonderingly at the piece of paper, at Sheila, at Madame Aleksander. The new game was no longer funny. He knew what the message meant. He was to leave this house and his new friends and all the happiness he had begun to find again. Madame Aleksander was clasping his hand with a pleading intensity. She was nodding and biting her lips and laying a finger on his to keep him silent, all at once.

Sheila said, “Casimir, we need some more wood for the stove. It is quite dead now. There’s supper to be cooked for to-night, you know.” She pointed the pencil to the written “Warecka 15” and kept it there.

“Shall I take Volterscot?” he asked slowly.

“No, I think he should keep Madame Aleksander here company, for I have to go out once more.”

Madame Aleksander gathered Volterscot, protesting with a strange, half-smothered whine, in her arms. She held him there, struggling frenziedly, as Sheila pushed the reluctant boy out of the door.

“Please,” Sheila said, as they reached the hall.

“As you wish, Pani Sheila,” he said. He looked slowly back at the room, at Madame Aleksander and the violently straining Volterscot, at Sheila. “As you wish,” he said again. He suddenly took the paper and underscored “Warecka 15” to show that he had indeed understood.

And then his footsteps, no longer light-hearted or clattering, faded into the distance.

Madame Aleksander’s face was drawn with sadness once more. She laid her cheek with its silent tears against the excited head of Volterscot.

“I must go too,” Sheila said. She struck a match and burned all the pieces of paper, being particularly careful that nothing but fine dust was left of “Warecka 15.” “I’ll be back quite soon,” she promised. She watched the last curling ashes and thought of the lonely boy walking blindly towards the strange address. What kind of people would welcome him? Her heart swelled with pity and affection. It choked her. At last, “I must go,” she repeated in a voice which seemed hardly her own. “I’ll be back soon.”

On sudden impulse she kissed Madame Aleksander’s wet cheek, touched Volterscot under his chin.

Madame Aleksander didn’t speak. She was biting her lip cruelly, her cheek still against Volterscot’s alert ears.

Hefner greeted her affably, “More than a few minutes,” he observed, “but better than I expected. How did they like their new rags? Did you have a touching scene?”

“Yes,” Sheila said. She let him talk of the victory parade as the car turned south into Ujazdowskaja Aleja and then south-west into Szucha Aleja. Sheila, seemingly intent on his phrases with a concentration in her brown eyes which obviously pleased him, was thinking of Warecka 15. She was thinking of a boy of twelve, with a new wool scarf round his neck, plodding obediently towards that street; of a boy concealing his unhappiness behind an unconvincing frown. If only she could have told him that he wasn’t just going to hide in a strange house, if only she could have said, “You may eventually join a guerrilla army,” how much more quickly he would have walked. But she hadn’t dared tell him that. He might not reach Warecka 15.

So she listened to the affable young man beside her, fixed her eyes politely on his face, and kept saying to herself. “Please let him reach Warecka 15. Please, God, let him reach it.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”