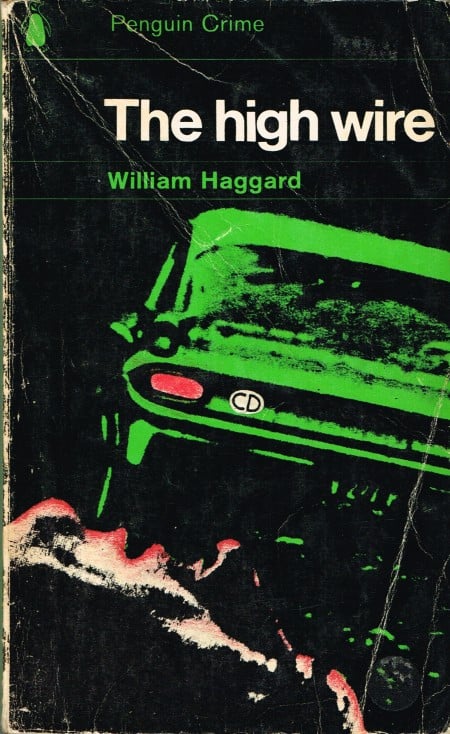

The High Wire (3)

By:

November 15, 2014

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize William Haggard’s 1963 novel The High Wire, the fifth title in his acclaimed Col. Charles Russell espionage adventure series — which, at the time, was considered by critics (if not the general public) superior to Ian Fleming’s Bond series. “Haggard lacked Fleming’s snooty dilettantism, and was better at creating subtle layers of political intrigue,” Christopher Fowler has written. “Haggard treats his women with more respect, too. They are investigators and heroines with lives of their own. As for exoticism, try Haggard’s character Miss Borrodaile, the elegant, black-clad, former French Resistance fighter with a steel foot.” Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The High Wire as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Robert Mortimer went back to the Security Executive. He wrote a careful report for Colonel Russell on everything which had happened at Sestriere. The Executive knew all about Project A, or to be accurate its business was to ensure that nobody else knew anything. The Executive had its own men at Maldington, and a senior officer at headquarters, Robert Mortimer in fact, charged with co-ordination. It was a very vague word and an awkward duty, since Project A wasn’t a secret but simply a possibility which the scientists of six nations must have scented. Robert Mortimer sighed. He knew about formal secrets and something of how to keep them (when, he remembered, an open society let him), but projects were different. What lay at the end of Project A was something which could change overnight the balance of power in Europe or, quite conceivably, it wasn’t a weapon at all. But that was known widely, in other and rival Powers. The thing was on in theory, but it was going to need massive luck. And it seemed that the. English had had it. The English were mad, but they didn’t commit enormous resources to programmes of abstract science. That wasn’t their form at all. So they must have had a breakthrough — small perhaps, nothing final — but enough to encourage them. Why otherwise build Maldington? Clearly, it had cost millions, and it had sprung from a wasteland with a speed which suggested that in any case cost was irrelevant. It was supposed to be the latest in engineering shops but nobody believed it. A board had gone up in the past ten days — ‘Sir William Banner and Partners’. Nobody believed that either. Sir William was an industrialist, and industrialists had experience, competitive know-how, which no government scientist had. So some physicist had stumbled on something, and Maldington had risen as his nameless monument. But Sir William had taken it over; Sir William could develop things, maybe produce and fast. The latest in engineering shops? Sophisticated eyebrows rose. That wire, dear boy, the dogs, the ex-sergeant majors absurdly disguised as doormen. It didn’t look nuclear, so….

Robert Mortimer frowned. He was technically ignorant of what went on at Maldington: his business was to keep the world so.

It wouldn’t, he knew, be easy. The others must be on notice too, the others would want it. The English had got on to something — what? Five Powers it could affect and one it could relegate finally. That Power was de Fleury’s.

Mortimer knew about de Fleury. He knew his private story and could guess his public aim. Major Mortimer took him seriously. It was fortunate Mary Francom was a woman.

Now he was sealing his report on what she’d brought him. He had told the facts simply, leaving judgement to Russell. Who would probably talk to Sir William Banner before deciding what to do about Rex Hadley. And as for Cohn, there were already papers. Mortimer had them himself since he wished to refresh his memory.

He began to read steadily. Mortimer had several dozen files which, with a change of name, would have done for Julian Cohn, and they had always troubled him. To begin with he didn’t understand the men and women whose dossiers they were. Mary Francom had been right, for Cohn didn’t live on journalism. His grandfather had owned a grocer’s shop, his father a chain of them. It was a company now with a considerable capital, and Cohn still owned most of it. He was third generation, ripe for the higher thought, but he hadn’t divested himself of the private fortune which his higher thought detested. He wrote for the left wing journals and he wrote very well, bitter little articles never quite scurrilous and never quite fair. Then he went home to a comfortable flat in Wheatley Street, paying the rent from a chain of successful grocers. Cohn was in the movement, very much so. Private fortunes were out of date — God, they were an outrage — but he went home to live on one, very cosily indeed. He was a part of a recognizable establishment, one smaller but just as definite as the other with a capital. Which he attacked incessantly. But he lived like his enemies, more so than most of them. It struck Robert Mortimer as odd. He wasn’t a moralist, Mary Francom had said so, but he had a sensitive nose for hypocrisy.

That was the background and it was all too familiar. It was what came after which was interesting to the Executive. For Julian Cohn had contacts, avant-garde lecturers and economists, novelists who called themselves committed; and, since he had means to do so, Cohn had gone farther than this twilight world.

He had very close contact with an embassy. It wasn’t de Fleury’s. One thing at least was certain: Julian Cohn wouldn’t have been working for de Fleury’s masters.

Robert Mortimer looked at his engagement book. He had an hour to spare and he put on his hat; he found a taxi and told it to go to Wheatley Street. There he dismissed it.

He looked around him, interested. The street was a bylane of doctorland. There were maisonettes one side, a block of flats the other, and a pub whose customers he could have sketched unseen. The comfortable little street ran at right angles between two others, the stroke to a capital H. It wasn’t wide and it had recently been metered. Mortimer looked around again, more interested than ever. He paced it out, seventy-five ex-Regular strides. He walked across, which was eight and a half. But on one side were continuous parking spaces, and all were still occupied. A few hours ago they would hardly have been clear, for this was a metered parking ground — doctors and dentists and a hospital round the corner. So take off two paces for a solid line of cars one side. Nor was the other clear. The metering wasn’t continuous here but it was more than half the street again. So take off another two paces. What you were left with was an effective road space of at most twelve feet, twelve feet of driving space connecting a street which was hardly important with another almost as tatty. Seventy-five paces long, so you wouldn’t have been belting it. Mortimer looked at Wheatley Street again. The snow had melted, frozen to an ugly ice. In a reliable car with first-class brakes he’d have been doing fifteen at best. It struck him as a very strange place to knock a man down.

Unless, of course, you’d meant to.

He walked thoughtfully to a telephone box, dialling a police station.

‘Macdonald? Robert Mortimer here.’

‘Good evening, sir. What can I do for you?’

‘That accident of yours — the one in Wheatley Street.’

‘Oh yes?’ The polite West Highland voice was cagey.

‘Nothing to do with us, of course. It’s just that we knew the man. We’d an interest in Mr Cohn.’

‘Indeed, sir?’ Macdonald was unexcited. An admirable policeman, he did police work admirably. He knew little about the Executive; he didn’t want to. ‘I can’t tell you much for we simply don’t know it. This Cohn, seems to have walked into the roadway and some fool sends him flying, and perhaps lost his head and drove on. We’ve not found a soul who saw it, but we may.’ There was a second’s hesitation, then: ‘There weren’t any signs of brake-marks, but the road was ice.’

‘Hadn’t they cleared it?’ Robert Mortimer hid a smile. He wasn’t falling for that one; he wasn’t disclosing that he’d been poking about in Wheatley Street.

Like a policeman, he thought. That was really a little naughty. He asked again: ‘Hadn’t they cleared it?’

‘You don’t know our Borough Council, sir.’

‘I didn’t know Cohn — not personally.’

‘Most respectable citizen. Lived with a housekeeper. Most respectable too. A Scot.’

Robert said quickly: ‘Of course.’ He knew it was expected.

‘He’s pretty badly hurt, they say. He’ll live or he won’t.’

‘Unconscious?’

‘Very. And probably for days. They took him to a nursing home.’ Macdonald named it.

‘I’ll just scribble the address down.’ Robert Mortimer was indulging a mild deception. He wasn’t scribbling the address down since it was one well known to him. ‘Keep me in touch, if you would. I don’t suppose there’s anything, but Cohn was a customer. We like to keep the books straight.’

‘Certainly, sir. Good night.’

Major Mortimer found another cab, driving south through a pompous street. A hundred yards down it he glanced at a familiar house. It was the nursing home named by the police. The road was stiff with nursing homes but this had been nearest to Wheatley Street.

Also it was Miss Francom’s. Who would recognize Julian Cohn again. Who’d know what to report and where.

On Sunday evening Rex Hadley was driving back to his new little house at Maldington. It was a small red box, prefabricated, raised with astonishing speed, and very ugly. But it wasn’t uncomfortable. A couple looked after him whom Rex had found waiting when he’d finally moved in. There had been a note from Sir William too. Sir William had interviewed the couple himself and Rex had Sir Bill’s assurances: the man drove well and the woman’s cooking wasn’t poisonous.

Rex looked at Maldington in the light of an early moon, driving alongside the perimeter fence. The administrative block rose in the centre, stark and unlovely; the enormous cooling towers shone dully in the moonlight. There was a mass of gantries, and piping ran between building and building, incalculably, twisted in an almost human agony. Maldington was high science and looked it; it was a laboratory — a factory in name — but a laboratory conscious of destiny. Here a handful of men and women might tip the scales of policy, of power in Europe. Under the moon it was somehow sentient, a night beast stretching in its accustomed light, silently flexing its muscles.

Rex reined his fancies sharply, driving on. Now there were smaller buildings, carefully spaced, the upper part slotted planking varnished brown and bright new glass below. They were as modern as a shoe shop. All were within the perimeter fence, six feet of chainwire or a little more, held upright on concrete posts. At the top the posts leant outwards, carrying on angle-bars what seemed to be barbed wire. Three strands were exactly that but the fourth was deceptive: if you looked closely there were insulators hidden in the stanchions carrying it; the current was turned on at night. Inside the fence were obstacles again, double and triple where it mattered. There, were doors which opened as you approached them. Properly, that is. If you approached them wrongly they strangely stayed shut. There were matters you couldn’t see, or feel, things which went bump in the night. At the heart, it was rumoured, was a good deal worse.

And as a light relief there were always the notices. Rex was near one now and he read it appreciatively:

He grinned, for the rubric tickled a cool humour. Patrol — that was excellent. It had something military but something domestic too. Patrolling dogs — dear me, they must be most intelligent. And what it might have said but didn’t: Savage Hounds — but no, that was quite un-English. Dogs lay on mats by winter fires, snoring and stretching, or dogs, trained and alert, stalked the fields with their masters. The friend of man — no, no, not savage.

Maldington was the strange emirate Sir Bill had delegated. Rex had begun to love it. It was his own.

He went on quietly towards his house, reflecting that security had its own conventions, the part of it called cover in particular. ‘Project A’, for example, was very untypical. It told you nothing and for once it was undramatic, whereas in the war they’d been wildly facetious. There’d been a plan to kidnap Rommel and they’d called it Sunglass; another to recapture the Irish Treaty Ports and that they’d called Bograt.

But they seemed to be growing up. Stumble on the chance of the biggest coup since the original big bang and they called it Project A. Rightly in this case since if the programme succeeded its product would be as conventional as the tide. No atoms, no fall-out — just an old-fashioned bang in an old-fashioned gunshell but ten or twelve times more powerful than an old-fashioned blockbuster bomb. Superior manpower would be largely neutralized since it wouldn’t dare concentrate. And armour — pouff! A rifle grenade would blow a tank a furlong. And all without fall-out, all without that tiresome sense of sin. No men with self-conscious beards, women in dirty jeans, cooling their nates on your doorstep. Just a nice old conventional bang but raised to the power of n. You needn’t be a statesman, even a soldier, to realize the implications. And the country which got it first….

Rex’s man put the car away and Rex ran a bath. He had been playing golf and was pleasantly tired. He didn’t play well but he enjoyed the exercise, and though Project A’s programme was something called Crash, it was an absolute rule that every man working on it must have thirty-eight hours leisure a week. Continuous. There was somebody called a welfare officer who shooed them away from Maldington. Wives weren’t allowed yet.

Rex looked at his private mail. It had arrived on Saturday evening but he hadn’t had time to open it. There wasn’t a great deal — bills and some circulars, a letter from a professional association. Irene had had friends and he hadn’t much cared for them. They’d left him when she had and she’d scared away his own. He mixed himself a modest whisky, remembering that last time he’d taken a drink or two he’d made rather a fool of himself.

But he’d learnt his lesson cheaply: that was over and done with.

The last letter of the pile was in a thick cream envelope, crested. Rex took out the invitation card, its edges bevelled and gilded. His Excellency the Ambassador requested the pleasure of the company of Mr Rex Hadley. Six to eight-thirty. R.S.V.P. to the Private Secretary.

There was a note with the invitation card and Rex read it frowning:

Dear Mr Hadley,

I have been hoping that we might meet again. I believe you said at Sestriere that you were having the first part of a holiday and were intending to go back there. By coincidence I may now be able to do the same. Meanwhile, I hope you will be able to accept the invitation enclosed. A few friends are coming on to my flat afterwards for a stand-up meal, and I shall be delighted if you can be one of them.

Yours sincerely,

Francis de Fleury

Rex’s first feeling was of irritation. Damn it, the man was a limpet. Rex wanted no part of de Fleury, nor of de Fleury’s world. He had just escaped from an intolerable domesticity and from the frustration in his profession which had gone with a foolish marriage. An allegedly social life around the embassies wasn’t what he wanted to replace it. He wanted something else and knew it; he would have admitted by now that it called itself Mary Francom. It was a pity about de Fleury but at least they weren’t married. Mary had told him her story: it wasn’t for him to blame her if she discreetly looked after herself. The decision to do so owned respectable antiquity, and at his age one shouldn’t be a prig. Prigs threw things away, rejecting a chance of happiness on some theory about women. Theories about women were for very young men. Mary wasn’t an Englishwoman and she wasn’t an intellectual. Irene had been both. Rex had had just about a bellyful of intellectual Englishwomen.

He sat down with his weak whisky, staring at the invitation card, his irritation fading into something less acceptable. He knew it was uncertainty, almost a foreboding. Mary had told him de Fleury’s profession: he was a military attaché, and Rex had been surprised. De Fleury wasn’t a rich playboy, or not all the time, and Mary’s manner had impressed him. It had been casual enough, but she had looked at him straightly, her grey eyes serious. It might almost have been a warning. Like, he remembered suddenly, something Julian Cohn had said. Besides, the invitation was a little odd — odd in itself. Rex wasn’t quite ignorant of the world of diplomats: they didn’t waste time on people who couldn’t serve them. A feeler or two, a cool assessment, then, for the unimportant, the smoothest of brush-offs. And production engineers, even good ones, were hardly important people in the world of military attachés.

Or were they? he thought uneasily. He was supposed to be in charge of a factory at Maldington, but it was one with barbed wire and dogs, strange buildings and stranger people. There had been much in the Press on Maldington, surmise and guesses.

Rex went to his desk, starting on an immediate refusal. He checked himself. But it was always these snap decisions which landed you in trouble. They looked so easy, obvious; so often they were unwise. Too often you committed yourself.

He’d talk to Mary Francom and he’d ask her advice. They were dining again tomorrow. She’d know about de Fleury and she’d be able to judge his motives. She had every opportunity.

But not for much longer, not for too long.

Major Robert Mortimer was on the telephone, listening very carefully to Macdonald. Macdonald was saying quietly: ‘You’ve an interest in Julian Cohn?’

‘We have.’

‘And I’ve an interest in a street accident, on the face of it an ordinary hit-and-run. I told you we’d found nobody who saw it, but I said that we might. And now we have. It was a boy coming back from school. There was rather a nasty mess and he was frightened, so he ran home to mother but held his tongue. Then there was the usual appeal for witnesses on the radio and the family heard it. The boy included. Mother says something like: “That happened pretty close to us”, and the boy begins to talk. Father thinks it over — he’s a pretty stolid type — but he comes to us this morning.’

‘With the number of the car?’

‘I wish it were that easy, sir. We haven’t the number, but the boy was a car fan and he noticed the make.’ There was a tiny pause, then casually: ‘It was a DS Citroën.’

‘Indeed?’

‘Indeed. But we’ve a little more than that. The boy didn’t get the number but he noticed something else as the Citroen drove away from him. He says it was going like a bat out of hell but he noticed the back of it. There was a foreign identification plate — the letters of the country of registration.’ A pause again. ‘In this case it was a single letter, one pretty early in the alphabet. To me that means nothing special but it might to you.’

Mortimer whistled softly.

‘You’re interested, sir? As Security Executive?’

‘I’m interested but I’m guessing wildly. We often do, you know. I’ve nothing to give you or I’d swop at once.’

‘A pity that, for we’ve something more to offer you. We’ve been doing a little police work.’ There was the slightest of emphasis, faintly ironic, on ‘police’. ‘Just the boring routine. We’ve been checking the car ferries just in case. The middle of the winter isn’t a busy time for them and it wasn’t too difficult.’ Macdonald’s voice became suddenly formal, the voice of a senior policeman in a magistrate’s court. ‘It has been ascertained that on the day of the incident only one car of the make in question and with the foreign identification letter referred to left this country by any ferry. Its number is of course available in the Customs records. These further show that the car in question was brought into this country the day before the accident.’

‘You’ve been busy.’

‘We’re policemen. And as policemen I should guess we’re at the end of it. Of course we’ve put the machine in gear on the other side but I’ll be surprised if it turns up anything useful…. A man brings his car over for twenty-four hours, no doubt with a cast iron reason. We’d still be a mile from a case in this country. We’ve the number of a DS Citroën which came here the day before an accident, and a witness who saw a DS Citroën involved in an accident. A DS Citroën, number unknown: an accident. Of course there’s the identification letter, but no court is going to listen to us if we put up a case which depended on a make of car and a foreign identification letter. There’d be trouble if we even tried. So unless Mr Cohn comes round again, unless he saw the number and remembers it — pretty unlikely, I’d say — and assuming it wasn’t a false one —’

‘Cohn’s still unconscious?’

‘Yes. Mr Cohn has had rough treatment. We’ve not much hope in Mr Cohn, nor for him. Still, if you’re still interested….’

‘I am.’

‘If you’re interested, I’ve something more. But I wouldn’t lean too hard on it. It’s quite a small thing and it might mean nothing. My informant may be mistaken…. You’ve used these drive-on car ferries yourself, sir?’

‘Often.’

‘Then you’ll know how they work. You drive your car on and round, give the keys to a sort of sailor, and then you walk up to the saloon. Sometimes, when they’re not too busy, they pick up a pound or two by doing a wash for you. They weren’t at all pushed on the night in question, and there’s a man who remembers offering to wash a DS Citroën. There was only one man with it and he declined the wash. Strong foreign accent, which isn’t unusual, but there was something which was. Or you may think so. It wouldn’t impress a court, though.’

‘Go on.’

‘This car-washer cased the job while the driver was coming in. It struck him as a little odd — so odd he remembered it. The weather was filthy and so was the car. All except that sloping bonnet and the bumper in front. They’d just been washed, and carefully.’

‘Thanks,’ Mortimer said. ‘Thanks very much.’

‘Good hunting, sir.’

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”