The Unconquerable (17)

By:

October 19, 2014

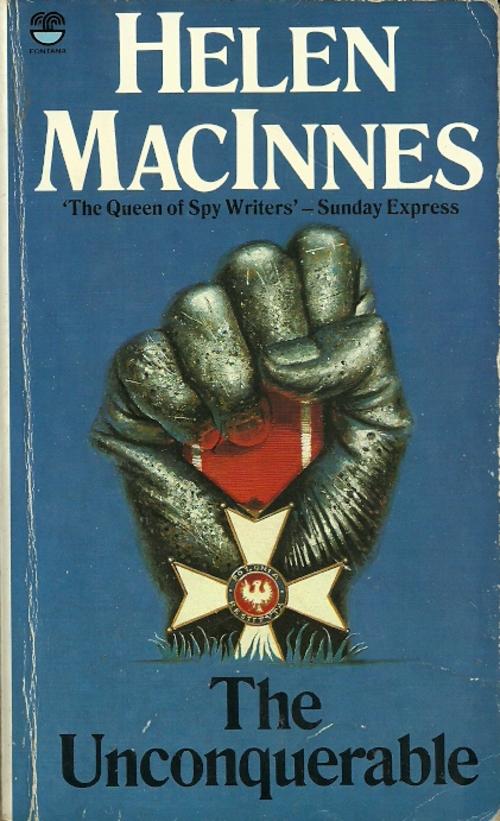

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

The porter’s house was empty. It looked as if it had been unoccupied since the night that Elzbieta and Sheila had been taken from it. The garden was in ruins. The remains of the anti-aircraft emplacement looked like a half-finished grave. Opposite the porter’s gate there was now another entrance to the courtyard. A gaping hole had been driven in the middle of that side of the block of flats, leaving a moraine of stones and smashed household belongings spreading towards the garden. Through the neatly sliced gap, with its remnants of flowered wallpapers and tilted picture-frames still clinging to the exposed walls, could be seen the black, burned walls of a church. Fire had seared the top floor of Korytowski’s side of the house, but his apartment was still there. Like the others which still gave shelter to their owners, its windows were neatly covered with bright-coloured cardboard. Their brightness was like the smile on a dead man’s face.

Sheila and Stevens climbed the stairs carefully. There was a tilt towards the well of the staircase, and the railings shook loosely when touched. The door’s framework had a lopsided look. The door itself had separated from its hinges and was propped shut. As their footsteps stumbled over the fallen plaster the door was lifted open. Two men looked at them, two men in stained and ragged uniforms with guns in their belts.

“Get the old man,” said one of the guards. The other left him holding up the door and watching the newcomers carefully. Sheila stared back. Even Stevens looked as if he hadn’t quite expected this. Mr Olszak’s invitation had scarcely prepared them for such a welcome. From the living-room came the murmur of many voices. Sheila quickened with excitement. The deathlike acceptance of the ruined buildings had gone. Here was challenge and defiance. Here was hope.

Korytowski, with a red scar taking the place of the bandage across his brow, led them through the hall into the living-room. He was excited too, for he only smiled and didn’t speak when he saw them. The large room was a warm mass of dark shapes. The only light came from a candlestick on Korytowski’s desk, so that those who leaned against the walls of the bookcases stood in the shadows. Afterwards Sheila wondered if the concealing darkness was intentional rather than economical. There were some women in the room. They sat on the few chairs. The men sat on the floor or stood beside the bookcases. All looked towards the desk, each with his own attitude of attention, as Olszak rose to speak. Above the candle’s broad flame the lines on his face were etched more deeply, the eyes were more sunken.

An officer, his torn coat draped round his shoulders, placed a chair beside Sheila. She looked up to thank him as she sat down. Even in the twilight of this room she saw his face had grown gaunt and white. There was a loose lock of hair which fell over his brow. His mouth held no smile now, and the laughter had gone from his eyes. For a long moment they looked at each other. Then as silently as he had come he had left her and once more was leaning against a bookcase. Adam Wisniewski. She remembered the warm evening sun as she had leaned out of a bedroom window, the black horse rearing in front of four white pillars, the cavalry captain who had looked up towards her and saluted as he dismounted. She remembered a dinner table and mocking brown eyes which had watched her as she had pretended to talk to Andrew. Adam Wisniewski. She forced herself free from her thoughts. Like Steve standing so silently behind her chair, like Wisniewski leaning with his tired shoulders against the bookcase, like the group of three workmen sitting at her feet, like the two young students beside her, like the priest, the soldiers, the women who might have been school-teachers or secretaries or housewives, the men who looked like substantial burghers, the men who looked like skilled craftsmen, she set herself to listen.

“…our last free day. To-morrow the enemy may come. We have this day, by the grace of God. That is why I have called you together. Some of us have met before, some have only been recruited to our ranks in the last few weeks, some have been chosen to join us in the last few days to fill the gaps in our ranks caused by enemy action. Our purpose is one, whoever we are, whatever we have been. We fight on. Poland will not die, while we still live.

“We meet here together for the first and last time. We have renounced our names. We have no families, no loyalties except one alone — our country. I have asked you to come to this meeting, innocently in ones and twos, carefully, secretly, not so much as heads of the departments of our organizations, but rather that you each may learn that you are not alone. That feeling will be important to you in your work in the months ahead. However heart-sick and despairing you may be, you will take comfort from the fact that we are all part of each other. And neither torture nor the threat of a painful death will allow us to betray what we know, for one word wrung out of our lips will mean not only the end of our own department, but the end perhaps of all the other forms of our resistance. Each of us will remember he is responsible for one phase of attack against the enemy. Each of us will remember we are dependent on each other. Without each other, organized resistance is lost.

“The time is shorter than ever the most realistic of us had feared. Before the enemy installs his occupation forces you must have your chief men and women in their chosen places, ready to organize and function. For safety, I have urged you to choose two deputies unknown to each other, who in turn choose two deputies who do not know each other. And so on — until we have a small army of patriots with the arms and the grip of an octopus. First, organize. Second, gather your strength slowly. Third, test your strength before you use it fully. For there is no hurry: the more thoroughly organized, the stronger and surer we are, and the greater will be our ultimate success. The war will be long, unless our allies betray us by making a peace with the Nazis. And I have no fear of that. As long as we have one friend fighting outside we can hope.

“In preparing for this new German tyranny, those of us who experienced the last…”

Korytowski was beside Stevens, saying something in a low voice. Stevens nodded. Korytowski bent down to repeat his words in Sheila’s ear. “Olszak wants you both to memorize all the details. That’s why you are here. Memorize the details, forget the voices and faces.” Sheila, wide-eyed, nodded in turn.

Olszak’s quiet, yet strangely moving, voice was saying “… planned this organization to be able to attack the methods of occupation we knew then. For the Germans always repeat themselves. We must also expect additional miseries due to the Nazi refinements on Prussianism. I have studied their methods in Czechoslovakia, and I have planned accordingly. But the organization is not static. We may have to add further departments to take care of any Nazi inventions which we have failed to visualize, remembering that when you are under the Nazis life is always worse than the worst you had imagined. Your monthly reports go either to our chief in Warsaw who is Number One, or to Number Three in Cracow, Number Five in Lodz, Number Seven in Lublin. That depends in which district you work from. Reports from your deputies are sent directly to you; their deputies furnish them with reports. By this system of steps and stairs we shall safeguard our work.

“Now, we shall review our departments. Some of us may work closely together, such as radio and Press. But remember that all information which you yourselves cannot use must be forwarded either to me, or to Number Three, Five, or Seven. We shall send it to the departments that can use it. We are together. However different our departments, we are one. That I cannot emphasize too strongly.”

Olszak paused. The men and women were motionless. Stevens’ arm was tense on the back of the chair. Korytowski beside them whispered, “Now, forget nothing.”

Olszak was speaking again. “Our first department has been given the name of Number Ten. Number Ten, are you here?”

“Here,” a voice said quietly. One of the watchful men straightened his back. The thin, anxious face waited expectantly.

“Department Ten: editing of news. You have your initial newspapers planned and located, your editors chosen and their staffs selected?”

“Yes.”

“Department Eleven: printing of news.”

“Here.” A broad-shouldered artisan raised his hand.

“You have the nucleus of a printing press gathered together and hidden, as we arranged? You have contacted trustworthy presses for secret help?”

“All set.”

“Department Twelve: distribution of newspapers.”

A young woman’s voice said, “All arranged as you advised. All we need are the papers.”

“Good. Departments Ten, Eleven, Twelve, will work as a unit. Make your final arrangements to-day.”

“All made,” said the quiet voice of Number Ten. The other two echoed him.

“Number Ten will also work closely with our next department, Number Thirteen: radio.”

A tall thin man with a bandaged shoulder said, “Here. Transmitters and receivers installed in key points. Hundreds of radio parts being hidden for future use. Reliable men are in charge. Sub-departments for sending and receiving have been formed. A special group for code messages is already at work. A network of six stations encircling our central station, but with our allies in the outside world. Smaller stations will form their networks round each of these six stations. Thus we shall maintain contact between the various districts of Poland and between Poland and our allies. The plan should be working smoothly and fully by the end of a year.”

“Excellent. Now we come to three departments working closely together. First, Number Fourteen: communication.”

“Here,” a businesslike voice answered. “Routes are being planned for the escape out of Poland of those in political danger. Contacts outside Poland are being established for two initial underground railways.”

“Department Fifteen: papers and passports.”

“Here,” a dark-haired man said. Sheila stared at him. He reminded her of some one. “Our chosen men are ready, but we must wait for the German issue of permits and passports before we can copy them.” The voice was familiar; an Aleksander voice. Stefan… this man was like Stefan. Sheila strained to see him better. Was this Stanislaw, the diplomat? His tweed suit, well tailored, was now stained and torn. There was a bandage at his neck. He still wore the armlet of the irregular soldier. Then Olszak’s voice caught her attention again.

“Department Sixteen: transit in Poland from one district to another.”

“Contacts established before outbreak of war. Main routes already planned. We found no lack of volunteers. The people are willing. But, like Number Fifteen here, we must wait to see how the Nazis order us about. We’re ready for them.” This time the speaker was one of the workmen in blue dungarees who sat near Sheila. He had the alert face of a man who has been accustomed to secret political planning. There was confidence in his voice and in his quick eyes.

“Good. All of us will need the help of Number Sixteen.”

The man grinned and rubbed his nose self-consciously. “We’ll take care of you,” he said. The others stirred restlessly as if they had relaxed into a grim smile for a moment.

“Our next seven departments might be put under one head, that of sabotage. But they are each so important in themselves that we have subdivided them and made them autonomous. Department Number Seventeen: railways.”

“Here,” a man with a greasy leather cap worn at an angle spoke up. “I’ve got my first batch of men all chosen. But we’ll have to wait until the Huns build the railways again before we can blow them up.” The group of workmen round him grinned, and then waited tensely to give their answers in turn. Two soldiers straightened their backs and held themselves ready.

“Department Eighteen: power-stations.”

“Here.” That man might be an engineer. White collar, roughened hands.

“Number Nineteen: fuel dumps.”

“Here,” said a workman with the armlet of the irregular soldier.

“Number Twenty: ammunition dumps.”

“Here,” one of the soldiers answered.

“Number Twenty-one: bridges, tunnels, canals.”

“Here.” This time it was a neatly dressed man who had lifted his right arm. A construction engineer, a draughtsman, a builder? Sheila couldn’t guess. In past life the man had been successful. You could tell that at least from his voice.

“Twenty-two: troop trains, shipment of arms and military supplies.”

“Here,” the second soldier said. He was a countryman. He seemed restless in this warm room.

“Number Twenty-three: factories.”

“Here.” The man carried the responsibility and pride of a workman who had risen to the position of foreman through his own efforts.

“These seven departments are waiting only to see what the Germans offer them.” The sabotage group nodded, and a variety of phrases to signify agreement formed a sudden chorus. Even Olszak’s face relaxed for one moment.

Then he said, very crisply, very evenly, “Number Twenty-four: assassination.”

Sheila took a deep breath, but the serious-faced student who answered “Here!” was as calm as Mr Olszak had been. “We, too wait for what the Germans have to offer us. Weapons are being hidden, men are being chosen. At present we intend to avoid indiscriminate assassination and reprisals. A few well-chosen key Nazis will be worth more than a thousand soldiers.”

“Number twenty-five: intimidation by anonymous messages, warnings, signs on walls and public places.”

“Here.” This time it was a woman, perhaps a school teacher, middle-aged placid, resolute.

“Number Twenty-six: whispering campaign to affect the German soldiers’ morale.”

“Here!” another woman said. “We are ready for both the men and the officers.” She was well dressed, with just too much care spent on her clothes and face. Her eyes were hard, her red lips smiled as if she were already welcoming the unwelcome customers.

“Number Twenty-seven: direction of citizens who are faced with deportation to Germany for forced labour.”

“Here,” a professional man said. He might be a doctor or a lawyer. “Those we can contact before they are seized will have their orders.”

“Hope you don’t have to give them to me,” one of the workmen said pointedly. The men around him again smiled grimly.

“Number Twenty-eight: maintaining the morale of the Polish population. Counter-action against the probable introduction of drugs; of cheap, crude liquor; of pornographic books and entertainment; of excessive gambling; with the purpose to demoralize our people.”

“Here,” the priest’s deep voice answered.

“Good. These last departments, dealing with morale — either attack on that of the Germans or defence of our own — cannot be fully envisaged until we see how the Germans use their power. But your men and women are ready?”

There was a solemn chorus of assent.

“Now we come to counter-espionage. Number Twenty-nine. That representative cannot be with us to-day. But I know him well. You can trust him, as I do, to achieve his purpose.” Sheila wondered if Twenty-nine were Olszak himself. Or was it Hofmeyer?

“Closely allied to counter-espionage is Number Thirty, who is responsible for contact with our allies in the world outside. Both will naturally work in close contact with Number Thirteen. Department Number Thirty?”

“Here. All initial contacts prepared.” This time there was no doubt. The quiet voice was Hofmeyer’s. Sheila looked in his direction, but he had chosen an especially dark shadow. No one, not even one of his comrades, was going to be able to identify Mr Hofmeyer.

“Now we come to one department which cannot be organized by the same method of deputies and sub-deputies as the others. For in this department of guerrilla warfare the leader works with a staff of specially chosen officers, and all must fight along with the men they recruit. The essence of successful warfare of this nature is participation and personal direction. Number Thirty-one.”

“Here,” Captain Wisniewski replied. All the voices had been eager. His was hard and angry as well.

“Yours will be a long task,” Olszak continued. “Such warfare can only be carried on after bases have been established, after ammunition and supplies have been collected and hidden, after your men have gathered in sufficient strength and have been trained to know their terrain and to work together.”

“We haven’t had much time to prepare.”

The listeners saw a smile on Olszak’s thin lips.

“Naturally,” he agreed.

The defensive tone left Wisniewski’s voice. “But we have made a beginning. Under the terms of capitulation all officers are to become prisoners. To-night those whom we have chosen will leave the city and make their way through the German lines. Our first base has been selected. We shall proceed there. Give us six months to collect and take what we need, to gather recruits and train them in this way of fighting, and we can start preparing our campaign. At the end of a year we should be strong enough for co-ordinated attacks, both in the countryside and in city streets. It will be one of our jobs to find which men are suitable for those different types of resistance.”

“Good,” Olszak said. “You will need the co-operation of Numbers Fifteen, Sixteen, Twenty, and Twenty-two. See them before you leave Warsaw.”

Adam Wisniewski nodded. The men of these departments were already making their way to where he stood.

“Our last department is that of education. Number Thirty-two: the organizing of secret Polish schools. We have no reason to hope that our children will, be allowed to learn anything except German ideas. During the last German tyranny our schools and our universities were abolished, and our language was banned. Then, for a hundred and fifty years, we depended chiefly on the mothers to teach their children. And they did it nobly in spite of imprisonment and punishment, for otherwise we Poles should have become either pseudo-Germans or one mass of illiterates. To-day we are organizing secret schools to be taught by trained teachers. If that is impossible in some locations then our schoolteachers will secretly help and advise the mothers. Number Thirty-two is still in hospital, I believe. He will be discharged to-morrow. He is sure of full support from his fellow-teachers.”

Mr Olszak paused and looked round the silent faces. “That,” he said, “is our programme. We may add to it or alter its direction, as the need arises. Any questions or suggestions?”

The red-faced soldier cleared his throat. “What about the farmers? The peasants should not be left out of this. They’ve got to be united secretly.”

“The farmers have their Peasants’ Party,” Olszak reminded him. “And so far no political opposition has ever managed to crush it. And many of our departments will contact the country people. We need their help in guerrilla warfare, for instance. They can smuggle food and horses to us. They can give us shelter and clothing. We haven’t forgotten the peasants. We depend on them now.”

The soldier nodded as if satisfied. Others rose to ask their questions. Twice Olszak noted down before him some new idea, but the question about religious persecution was referred to the Church. “Our priests have always defended us,” he said. “The Church of Christ will know how to save.”

The problem of safe hiding-places for those in sudden danger, of houses where men wounded in this new struggle could be secretly nursed back to health, was answered by Department Number Sixteen. “We’ll take care of you,” Number Sixteen said once more.

“One question has not been asked,” Olszak said finally. “And that is the question of reprisals taken by the Germans on civilians for acts which our agents will commit in the course of duty. If the Germans follow their practices of 1914 to 1916 in Belgium, or of 1916 to 1918 in Poland, we can expect harsh treatment for the innocent. But we must remember that every man, woman, or child who is murdered by the Germans in reprisal falls as a soldier on a battlefield. We ourselves face death. We have all accepted that constant threat. If we ask no quarter for ourselves in the secret battle which we fight then no other Pole will hesitate to pay the price we ourselves are willing to pay. For unless each of us is willing to die we can never win. The choice is this: either we let our purpose be conquered by the blackmail of reprisals, and then we are conquered too; or we harden our will and our hearts, knowing that without sacrifice the Germans would have a comfortable victory, and Poland would be for ever dead.”

“Never, never!” the editor exclaimed with rising emotion. Others joined his cry, “No, never, never!” Olszak silenced the threatened shout with hands that commanded obedience. “Quietly, quietly. We must not be heard. Quietly.” And then his voice strengthened. “Poland lives, for Poland fights on,”

he said. He sat down abruptly, shading his eyes with his hands.

The priest rose. The room’s sudden silence was broken by the rustle of kneeling men and women. Their voices repeated a short oath of allegiance, and their heads were bent to the priest’s brief prayer. It had the intensity, the finality, of a prayer before battle. “…God, in whom we trust,” the priest ended, and his arms fell slowly to his side, and the men and women rose to their feet.

Stevens stood up quickly and helped Sheila to rise. He avoided her eyes and pretended to be absorbed in the people around him. Korytowski was beside them again.

“You understand everything? You will remember?” he asked Stevens anxiously, and the American nodded. Korytowski noted the puzzled look on Stevens’ face. “Olszak will explain,” he said. “We are to wait for him next door. The others will take some time to leave. They cannot walk out of here in a body, you know.” He turned towards the door, obviously intending that Sheila and Stevens should follow him. They did so unwillingly; they would have preferred to stay in the room and watch these people. But perhaps Olszak wanted them out of the room for that very reason. Sheila’s last glance round the room ended with Adam Wisniewski. He was still leaning against the bookcase, his officer’s long coat thrown cloakwise round his shoulders. His face was that of a man who had been savagely wounded, of a man who was so exhausted emotionally that all he could do was to stand unmoving, his face a determined mask, his eyes fixed in a brooding stare on the opposite wall. Number Sixteen was talking earnestly. Wisniewski answered. Number Sixteen nodded as if pleased. Wisniewski was talking again. Sheila suddenly realized that the mask was there to hide his wounds, that there was a depth to this man which she had never suspected. But then, she thought, she had never given him a chance to prove what he was or what he wasn’t. And it was too late now. They would never meet again. The time was out of joint.

For one moment his eyes looked directly at the doorway and rested on her. She felt the look rather than saw it. Russell Stevens pulled impatiently at her sleeve. He too was watching Wisniewski.

“Come on,” Stevens said, “we are supposed to be in the next room.” He looked at her in that quick, clever way of his. He stood aside to let her pass into the hall.

Adam Wisniewski had stopped talking, stopped listening. The men beside him saw him take a step towards the door. One of them repeated his question quickly. “You said you would need some one in the villages surrounding your camp to be responsible for guiding your recruits. In each village? Or in a key village, Captain?”

Wisniewski halted. She had gone, and the American was following her.

The men round him were waiting for his reply. He turned his back to the door. “In each village,” he said. “We’ll need help from every village in the district, not just from one or two.” Grimly he forced his whole attention on the man’s answer. If there had been no time for personal feelings in the last four weeks there was even less now.

In the hall Korytowski waited impatiently for Sheila and Stevens. “This way,” he was saying, “this way,” as he led them to the guest-room. Behind them was that low, busy murmur of voices. The two soldiers on guard leaned against the twisted door.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”