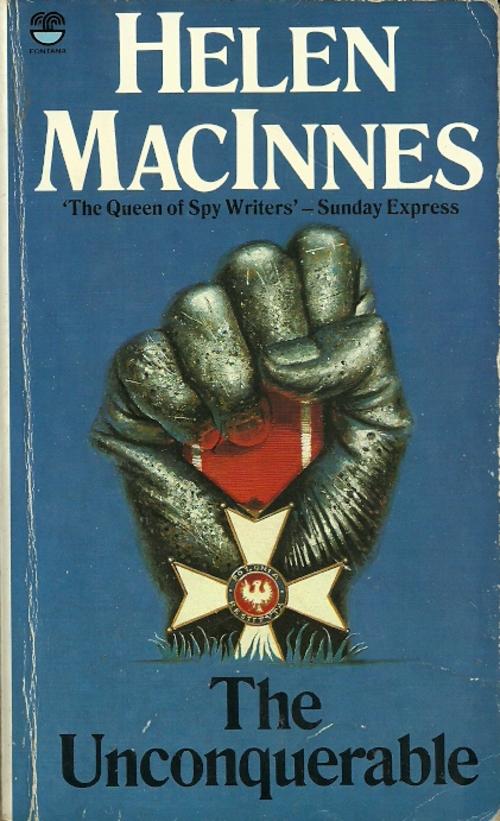

The Unconquerable (15)

By:

October 8, 2014

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

Sheila had lost all count of time.

When the door opened it wasn’t Stevens or Schlott or any of the others. It was Olszak, a thinner, wearier, grimmer Olszak.

“You’ll catch another chill,” he warned her. His calm voice brought her back into the room. “And some one may think you are showing a light to attract enemy planes.”

Sheila guiltily pushed the board back into its position across the window. “I forgot,” she said inadequately. “I truly forgot about the candles.”

Mr Olszak was smiling. “Frankly, I don’t think it matters so much now. But it’s a waste of good candle. How’s your hand?”

“It’s all right.” She looked at him quickly. “Who told you? Steve?”

“Yes. I found him at Korytowski’s flat when I reached there to-night. He has now gone with Korytowski to find Madame Aleksander.”

“Should they tell her so soon?”

‘They were discussing that when I left them. Their courage in that respect was very low. You may see them here instead.”

“Why didn’t you go with them and give them some support?”

“Well, Stevens was worried about you alone here. And I thought I’d like to see you.”

Sheila was touched that this man should have made the frightful journey through the streets to see her. She smiled.

“So you’ve forgiven me for nearly killing you?” Mr Olszak asked. “I hardly expected such a warm smile of welcome. Thank you.” He sat down at the table. He thought, It would be wise to talk about past things and to avoid to-night’s happenings. Sheila’s eyes were too hard, too bright. “Well, we got the woman, Elzbieta. Again, thank you. You did a very good job.”

“What about the man?”

“Henryk, or rather Heinrich Dittmar? He never came back to the porter’s lodge. He has disappeared.”

Sheila suddenly remembered the feeling of being watched as she had entered the police car in the dark street that night. Perhaps she-had been right, after all…. Perhaps…

“Yes?” asked Mr Olszak.

She told him what she had imagined that night and then had laughed away.

“If you were right we shall soon know. He will make it unpleasant for any of us he can recognize again. You will be all right. In fact, your case will be stronger with the Germans. If I remember rightly, one of my men had you in a very decided grip, which rather distressed me at the time.”

Mr Olszak poured himself some vodka. “I am glad,” he went on in his quiet, smooth voice, “that you recovered so well from your illness. You are still somewhat thin and probably — if I could see your cheeks — too white. But I must say you worried me for quite a while. You never thought I had a conscience, did you?”

“I think you believe in what you do, and nothing will stop you.”

“Same thing. Won’t you have some wine?”

Sheila shook her head. She had promised herself the pleasure of giving Mr Olszak a shock whenever she saw him again. And here he was, and she couldn’t remember what she had been going to say to him.

“Why don’t you wash your face?” Mr Olszak, it seemed, was determined not to let her think.

She stared at him. He was drawing a handkerchief out of his pocket as he went over to the bucket of water. “Come here. I’ll get rid of the worst streaks.” He bathed her face carefully, and while she finished the cleaning process he searched for a towel. Madame Knast’s best curtain had to suffer some more tearing.

“Organize yourself. That’s the thing. Organize,” he was saying. He surveyed their joint efforts critically. “Much better. But, as I thought, too pale. Did you eat all the butter I sent? And the eggs? And did you drink the wine?”

“I ate and drank everything. I couldn’t stop eating. Barbara said ——” Sheila’s voice faltered.

“Comb your hair. It’s terrible,” Mr Olszak said quickly. Then, as she looked round in a puzzled way, “Isn’t there a comb here?” He fumbled through his pockets.

“My handbag. I can’t remember what happened to it. I had it ——” Stevens had taken a sack of sand over his shoulders, and he had left her, and she had helped the young girl, had used both her hands to grasp the slipping, heavy corners of the sandbag. And then there had been nothing but hurry and effort and strain…

Olszak, watching her eyes, said sharply, “What’s that tearing your pocket’s seams?”

She looked down slowly and began to laugh. “My handbag. I jammed it in. I must have.” It was tightly wedged into the pocket. Her coat tore further as she tugged and pulled.

“Easy now,” Mr Olszak was saying. “There’s a nice coat.” He didn’t add “And it may be a very long time before you have another one like it.”

Sheila was still laughing as the bag came free.

“Stop that. Stop it, and comb your hair. Here, give that bag to me.” He opened it and his thin fingers searched quickly for the comb. “I remember the first day I looked into this small contraption. I wondered how anyone could ever cram so much inside. Do you remember that day? In Colonel Bolt’s office?”

Sheila took the comb and began tugging at the ends of her hair. They were harsh and singed. Her eyebrows had the same dry feeling. So had her eyelashes.

“Do you remember?” Mr Olszak insisted.

She nodded. As she combed her hair she was remembering. Mr Olszak and Mr Kordus and Steve. Steve who knew so much without understanding the full meaning of what he knew.

“How is Colonel Bolt?”

“Everywhere. The man’s energy is boundless.” There was a little smile in Olszak’s eyes as if he believed in other ways of spending one’s energy.

“And how is Mr Kordus?”

The smile was still in place, but there was a hard edge to it. “When did you hear of Kordus?”

The question took away much of Sheila’s assurance. She heard herself give the direct answer she hadn’t meant to give so quickly.

“Steve heard that a Mr Kordus was Special Commissioner to the Security Police.”

“I believe he is. But who told Stevens?”

The story was neatly extracted with Mr Olszak’s usual skill. Sheila was left with no feeling of triumph at having jolted Mr Olszak, who had consistently dominated her since their first meeting. She began to wish she had never given in to her impulse to watch Mr Olszak jump. For he hadn’t. On the contrary, he was in full cry after a probably innocent Stevens.

“But he has no axe to grind,” she protested in the American’s defence.

“My dear young lady” — Mr Olszak was at his silkiest — “have you ever known a journalist without an axe to grind?”

“I’m sure he would have told you himself whenever there was time. He’s been busy.” Somehow her sarcasm was wasted. She said, suddenly uncomfortable and chastened, “Shouldn’t I have told you, then?”

“Of course. And before this. And found out the name of Stevens* informant, who points and talks too much.”

“But the man didn’t know you were Olszak. He pointed you out as Kordus. And Russell Stevens didn’t tell him the truth.”

“Stevens is really too inquisitive.”

Sheila’s temper flared as her worry over Stevens grew. “All right, then. I shouldn’t have told you. I should have let you go on thinking that no one ever found out that Olszak was Kordus, or Kordus was Olszak.”

“No one knew, except three men, who made my appointment possible, and who are working with me. No one knew…. See, you’ve shaken my confidence, Miss Matthews; I should say, ‘No one, I hope.’ Does that please you?” There was a gentle little smile round the thin lips. She was not only worried, but ashamed.

“I’m sorry,” she said miserably.

“No, don’t be. I’m glad you had the very natural impulse to — shall we say, tease? You’re a high-spirited creature, Miss Matthews, and you’ve resented the way I’ve used the curb and the snaffle. You don’t like a tight rein, do you?”

Sheila smiled in spite of herself. Mr Olszak’s idea that women were like highly bred horses amused her. “And now you are giving me a lump of sugar,” she said.

“It’s surprising,” Mr Olszak said, “how well we understand each other.” And then he was silent, his arms folded, his chin sunk, his eyes watching the flickering candle. “When a man knows too much,” he said at last, “either you make him one of your party or you eliminate him. These are the only ways to silence him.”

Sheila stared. “Not Steve!” she said. “He’s on our side. He will promise to keep silent. I know he will.”

“Promises are not so binding as dangers shared. Promises are merely good intentions. They are not enough. You see, Miss Matthews, every day and every hour make my plans more real. You’ve seen Warsaw. You know, as I know, that nothing more can be done. We have nothing left, neither light nor water nor food nor medicine nor ammunition. Not even clean air. But, although we shall have to capitulate, the battle will go on. As long as we have one ally left in the world outside we will fight. Even without that ally we’ll fight. We must. No nation is ever free who lets other nations fight for its freedom.” He regained his calm voice and said, “You see, Miss Matthews?”

“I see.”

“Did Stevens ask any questions about me?”

“Nothing very much.”

Olszak looked almost comical in his sarcastic disbelief. Then he relented. “Don’t worry so much about your American friend. I happen to like him. Why don’t you sit on that couch? It’s comfortable at least.” He rejected his own longing for sleep and searched for something to say to this girl whose eyes were still too hard, too bright. She had taken his advice, but she was sitting bolt upright on the couch, resisting its comfort as she resisted consolation. She would keep staring at the boarded window as if she could still see that sky smothering the city and its suburbs. He could feel its colour in the heat of this room. He thought of the streets across the Vistula. By this time… Well, he thought, what good will worrying do? Either he is alive, or he has been killed. Worrying will do no good.

The silence had become as intolerable as the heat. Olszak moved restlessly. He said, his thoughts still across the river, “You have met Adam Wisniewski, haven’t you?”

At first he thought she hadn’t heard him.

And then she was saying, “Is he dead too?”

He looked at her curiously. “No,” he said quickly. “He’s alive. At least he was very much alive two hours ago.”

Again there was a pause, and her face was quite expressionless. Then she suddenly bowed her head, and all he could see was the crown of smoothly combed hair.

What’s wrong now? he wondered. He saw her body relax, and he knew that whatever he had said hadn’t been wrong after all. For a moment he sensed something which he couldn’t explain, couldn’t fit into a logical pattern, and it exasperated him. There were so many tangents to a woman’s way of thinking. Men were simpler. Either they thought in the same or in a parallel direction as you did, or their way of thinking crossed yours at a decided angle. But these women… and the younger they were, the less understandable. Youth in itself was so involved. What was the process of becoming old but a choosing of the essential things, a discarding of too many impulses, a forgetting of too many dreams? How would it feel to be young again and have so many personal emotions cluttering up one’s life? These young people would pity his age, his dry way of living. They would never guess the relief he felt because he had achieved a perspective on life. He was master of his own mind and of his emotions. He depended on no one. He was less vulnerable. He indeed travelled fastest who travelled alone.

Sheila had fallen asleep. Quite unexpectedly her eyes had closed, her body had slumped forward, and she was as unconscious as if an ether mask had been covering her face. She would have been surprised to see the care with which Mr Olszak straightened her into a more comfortable position and covered her with a blanket. She would have been surprised to see him wait so patiently beside her until morning, and with morning an exhausted Stevens and a grim-faced Korytowski.

She awakened to hear Steve’s over-hearty, “Nice domestic scene.” Mr Olszak only nodded benignly. He let the other men talk on. They had been unable to speak to Madame Aleksander. Her hospital had been bombed again, and she had been too busy with the remaining nurses moving the survivors from the courtyard, where they had been dragged to safety, into another building.

“I’ll wait until to-morrow,” Korytowski repeated. The lines on his face, thin and white under the soiled bandage round his head, were deeper. His eyes were dark caves; the blue light had gone from them.

The American threw himself on the floor beside the couch. He seemed relieved to have found Sheila so quiet and composed.

They talked spasmodically of the city.

No one mentioned Barbara.

Then Mr Olszak said to Sheila, “I think you need more sleep. It will be easier next door.”

She knew what that meant. As she left the room she looked at Steve. Her tired eyes said, “Steve, be careful. Don’t be smart. Be ignorant and careful. And give the right answers.”

He was looking at her too. He saw the expression in her eyes and thought, she’s as unhappy as hell. To the two men he said as the bedroom door closed quietly, “She must have been very fond of Barbara.”

Edward Korytowski closed his tired eyes, nodded wearily. He was thinking of his sister Teresa. Barbara was the first of them to go. Or was she? What of little Teresa, or Stefan, or Andrew, or of Stanislaw? The longer he postponed breaking the news, the harder it was going to be for him to do it. He ought to have insisted that they should search to-night until they had actually seen Teresa. But both he and Stevens had been loath to find her, to tell her. They had welcomed the excuse that the time was ill-chosen. And if there hadn’t been that excuse they would probably have found some other reason. The city was being bludgeoned into unconsciousness, its grip was weakening. Before the end was called anything could happen. Why not wait until the death of the city? If Teresa or he was still alive then, that would be time enough for her to know. If she weren’t alive, then he would have spared her one sorrow more. He looked at Olszak as if for help. Michal would know what ought to be done.

Korytowski rested his head wearily on his arms; his mind had begun to reel as if his emotions had made him drunk. Helpless anger and grief gave way to hate. He could do nothing but hate. Hate the men who had ruined his country, shattered his city, killed his people so ruthlessly. One month ago they had all been living here in peace; sleeping, eating, working in peace. There had been light and warmth and flowers in the streets, there had been music, there had been people who laughed. There had been families and birthdays and visits to friends. There had been books to read in neat rooms, with only the voices of children playing in the gardens or the singing of the birds to break the quiet. The sky had been dark and cool at night, unclouded blue in daytime. And as he thought of these things he could do nothing but hate. He had felt this since the first bomb had fallen, but Barbara’s death released it from the secret places of his heart. It was now in command of him. All he could do was to hate. And he hated the Germans all the more for having taught him to hate like this.

Stevens, watching him, felt an upsurge of pity. The gentler you had been in your own life, the harder it was to bear all this violence.

Korytowski suddenly rose from the table. “I must find Teresa. I must tell her,” he said thickly.

“Wait,” advised Olszak, “wait until I can come through the streets with you. I shall go with you to Teresa.”

“Then you would tell her?”

“Yes. Teresa never avoided bad news in all her life. She would prefer to know.”

“Let us go now, then.”

“Shortly, Edward.” Olszak turned to Stevens. “Well, it will soon be over now. Listen to that new barrage since dawn broke…. What are you going to do, Stevens?”

“Can’t seem to think about that.”

“Surely you have plans?”

“Thought I had. But now that it’s near the end, I don’t know.”

“Why don’t you go back to America at once? Your Warsaw story will still be news for another week or two. You could tell the people outside how we fought in here. How Warsaw Fell. Exclusive.”

“Shut up, Olszak.” Stevens had risen to his feet and was standing over the Pole. “Shut up. I’m not so much under control these days. Perhaps I don’t want to be under control. So shut up.”

Mr Olszak seemed far from offended by the American’s savage tone. The sarcasm was gone from his voice when he said, “But perhaps you could tell them of our mistakes. For we have faced a new kind of warfare, and we didn’t know how to meet it. No country does, unless it has been studying war and war only for the last seven years. Whatever our faults as a nation, we have at least been a willing guinea-pig in the cause of humanity. They could be warned in time through us.”

“You mean I should go and give them advice? Me? I’d never stop talking if it would do any good. But you don’t talk a democracy into anything. Each member wants to do his own thinking, his own talking. The people make up their own minds. If you try to rush them they start yelling holy propaganda. It was the same with the British. They had to argue about Czechoslovakia before they decided Germany was dangerous. And it’s the same with all forms of democratic government in Europe. They are still discussing the war and voting on it at elections. How can you expect America to be any wiser than countries on Germany’s doorstep?”

Korytowski said suddenly, bitterly, “Then the sacrifice is all in vain. Other countries may be attacked without warning and suffer cruel defeats, because they would not see what happened to us.”

“Not in vain,” Olszak said. “In the end we’ll win. Even if there are few Poles left, even if all Poland is entirely devastated, there will be other lands where there still are railways and factories and modern housing. By taking the first blow from the German fist when it was strongest, we may have helped to preserve buildings and lives in other countries. So in the end well win, for Poland will live in the hearts of men. Or, do you think,” he added with his peculiar smile, looking so innocently at Stevens, “that men will forget us as quickly as they forgot us after we saved Europe from Mohammedanism?”

Stevens didn’t answer.

“You know, I like you. Just as I like that girl next door,” Olszak said unexpectedly. “You both have that same angry, helpless look when you contemplate future injustices which you hope won’t, but which you fear may, happen. But let me ask another question. Why should you worry whether your return to your own country would be valuable? Why don’t you just return, take up any new assignment, and go on building your life like millions of other fortunate young men?”

“Hell, no. What do you think I’m made of? Do you think any of the foreigners here, who have been through this with me, are going to go away to their different countries and turn off these last few weeks like a water tap? I guess we were all committed permanently when we first decided to stay. We didn’t know it then, but we chose sides all right.”

“You are decided, then? You are going to fight on?”

“We all are. There’s another American here. We’ve talked of getting to England and learning to fly a bomber. There’s a Swede I know. He’s staying in Warsaw, at his job with the American Bank. But he thinks he has enough contacts to be able to smuggle people out of Poland. There’s a Frenchman and an Englishman; they are going to reach their countries by Rumania and then enlist in their Air Forces. We all want to be on the giving end of a bomber, just for a change. But there isn’t one of us who is going to start tending roses in his own back yard.”

“What is your Swedish friend’s name?”

“Schlott — Gustav Schlott.”

“His idea has certain possibilities. But it needs silence. Tell him to keep absolutely quiet. Has he any Polish friends he can work with in his future enterprise?”

“I guess so.”

“Find out their names. Bring them to me to-morrow. That will be the twenty-seventh of September. Come to Korytowski’s flat at three o’clock in the afternoon. Now where can I get in touch with Schlott if I want to see him? Not at the bank. Preferably some place more private.”

“He’s living here now. If you wait long enough you’ll see him.”

“God forbid.” There was such an expression of alarm on Olszak’s face that Stevens grinned.

“Some checking up in order first?” the American asked innocently.

“You talk too much. What is worse, you think about things which are dangerous. We need friends. But we don’t want friends who are merely interested. If that is the most they can feel for us, then they are a danger to us the moment the Germans take over the city.”

“What are you getting at? If you think I’d give information to a lousy Hun I’ll —”

“You’ll what?” asked Olszak mildly.

“Skip it. Stop ribbing me. My temper is not what it was.”

“Neither is mine,” Olszak said with a touch of steel in his voice.

“What are you getting at?” Stevens said slowly. Incredulously he added, “Don’t you trust me?”

“I can trust no one until he has proved himself. Do you trust me, for that matter?”

“No.”

The two men looked at each other, and then Olszak laughed.

Korytowski, watching the American’s face, said quickly, “Michal. I rarely interfere, but I feel that all our nerves are frayed to breaking point. We know Stevens. He’s a good friend. He’s been fighting with us. What more proof do you want?”

“Only a very little more. But first let me ask, what does Mr Stevens intend to do with any information he has recently gathered? Not telling it to the Germans is only a negative plan. The Germans don’t always wait for people to tell, or not to tell. Suppose you were in London or New York. Suppose you were at a party and there met a charming woman or a sympathetic old man who deplored Poland’s situation. In your friendship for us, might you not rise to our defence? Might you not say that you knew there were certain men in Poland who were going to fight every attempt at domination? Later in the evening you would find yourself being asked about life in Warsaw before the war, about the people you had known there. Then months later you might learn that Korytowski, or I, or one of the men you used to meet at the flat, had been arrested. For the Germans are logical. If you knew about it it was only through the people you had known in Warsaw. That’s how it can happen. I know. I’ve seen how they have approached exiled Czechs here in the last years. Always very innocently, always very sympathetically, and never as Nazi Germans. Even the cleverest man can be duped by these agents. For there are moments when it is hard to keep silent, to keep from denying a lie or from justifying your friends. Yet the only way with these Nazis is to be able to seem callously silent. Can you do it, Stevens?”

The American shook his head slowly. “I’ll never be able to converse again. Damn you, you know I like a good argument.” He laughed ruefully. “I may as well admit now that I said I didn’t trust you because I was mad at you for not trusting me.”

“That’s better,” Korytowski said in relief, and relaxed again. He began pouring drinks into the measuring-glass and a shaving-mug.

“Here, what’s happened to my best crystal?” Stevens said in surprise, and looked round the room as if he were really seeing it for the first time. He cursed softly and steadily.

“Some one has been drinking a toast,”, Olszak said, and pointed to the corner of the room where broken wine-glasses were scattered. He handed the shaving-mug to Stevens. “Do you feel like a toast?”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning that I have a job for you to do. It will put you on the Nazi black list. It makes you one of us — not just a sympathizer, but an active member. If things go wrong for you I must warn you that the American consular representative could do nothing for you. I am giving an invitation to danger.”

Stevens raised the shaving-mug. “Good-bye to the bomber,” he said. “I’ll fight your way. On the receiving end.” He began to drink.

“You know what you are giving up?” Olszak asked slowly, raising his drink to his lips.

Stevens looked towards the bedroom. “If she can do it what’s going to stop me? When did a limey ever do what a Yank couldn’t?”

The kitchen measuring-glass and the shaving-mug smashed against the wall and added their large coarse fragments to the delicate ruin of crystal on the floor.

The bedroom door opened, and a startled Sheila stood there.

“Come in,” Olszak said almost genially, “come in, Sheila. We didn’t need to shoot him.”

Sheila relaxed. She smiled at Olszak. Until now it had always been a very careful “Miss Matthews.” She knew that somehow he was pleased with her.

“What’s that? Shoot who?” Stevens asked, with more vehemence than grammar.

Men’s voices and heavy footsteps sounded on the staircase. The tension in the room reappeared. Olszak was already at the door. Korytowski paused to kiss Sheila, and to shake Stevens’ hand.

“To-morrow afternoon. Three o’clock. Bring Sheila. Your jobs begin then,” Olszak said softly, and left the room.

“Hello,” Bill said as he entered at the head of the tired group of straggling men. “Who were the two old geezers we passed on the stairs?”

“Looking for Madame Knast,” Stevens said briefly.

Sheila’s eyes met his and smiled approvingly. “You’re back early.”

“There’s little to be done. It’s going to be a day of heavy shelling. Most people are making for the cellars. We’ll have to wait until this barrage slackens.”

The others were filing slowly into the room.

“You’ve additional guests,” Schlott said.

Stevens looked at them. “So I see. Well, we have still got a floor here,” he said. “How’s the world outside?”

“Pippa isn’t passing,” Jim said slowly. “God’s not in His heaven.” He opened his jacket and set down a small, thin, frightened dog on the floor. He fondled the shivering little animal, scratched the ears lying so flat against its head.

“Carried him all the way here,” Schlott said. “He’s crazy. Does he expect us to eat a dog that made friends with us? I didn’t adopt him. He adopted me. What could I do? He wouldn’t be a bad-looking little tyke if he were clean and happy.”

The shivering dog, its tail tucked well between its legs, moved uneasily round the room. It came to Sheila and cowered at her feet.

“He’s filthy,” she said softly, sadly. We all are, she thought. And we are all just as afraid. She rubbed the dog’s head gently as the men talked. She felt her eyes close in spite of her attempts to hold them open and be polite. The dog had stopped shivering. He looked up at her. As one human being to another, he seemed to be saying, just what is wrong with the world these days?

“How’s your hand?” Steve was standing beside her. She smiled for an answer; she was too tired to speak. He pushed her shoulders gently down on to the couch. The dog jumped up beside her, and no one had the heart to put him down. Sheila listened to the men’s voices growing more blurred. The candles became a haze. The dog stared at her solemnly. She scratched his ear and his watchfulness relaxed. He settled comfortably and gave a small sigh.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”