The Unconquerable (14)

By:

October 5, 2014

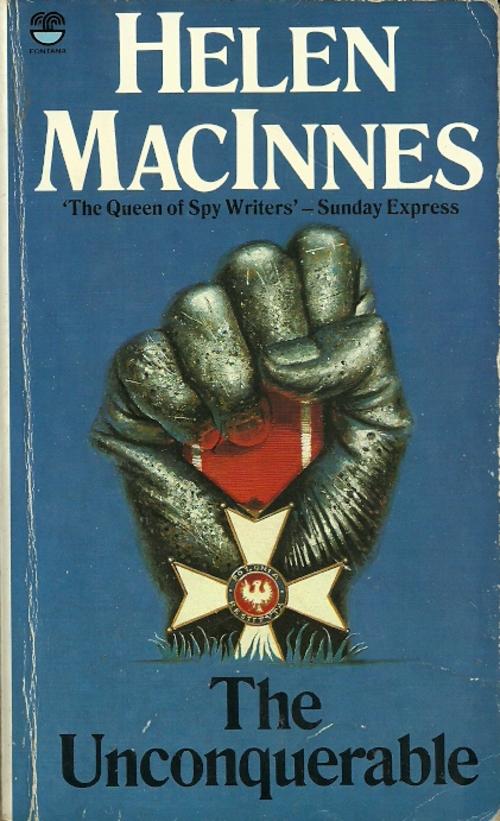

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Helen MacInnes’s 1944 novel The Unconquerable (later reissued as While We Still Live), an espionage adventure that pits an innocent English woman against both Nazis and resistance fighters in occupied Poland. MacInnes, it’s worth noting, was married to a British intelligence agent, which may explain what one hears is the amazing accuracy of her story’s details. Under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the Save the Adventure book club will reissue The Unconquerable as an e-book for the first time ever. Enjoy!

In the eastern suburbs across the river Vistula the cloud of dust from crumbled bricks and shattered cement blotted out the night sky. To the men, crouching behind the ragged walls of houses, or lying in trenches slit through the rubble of gardens, there was left neither night nor day. Time was remembered only by the gnawing hunger under their belts, by the taste of sulphur and lime on their parched tongues. None of them turned to look at the flaming city behind them to the west. Their red-rimmed, sleep-heavy eyes stared towards the east, towards the shroud of dust, suspended like a cloud on a volcano’s rim, which wrapped their enemy round.

That afternoon, in one of the smaller streets which ran parallel to the main road into the city, a group of nine men, two of them wounded, had settled themselves in the little Café Kosciusko. Formerly it had been a basement room. Now the upper part of its window, which reached above street level, served very adequately for a combined machine-gun slit and observation post. The machine-gun was silent. Like the watchful man beside it, like the others resting wearily behind it, the gun waited. Above the men’s heads, above the gaping ceiling and the empty space where two other storeys had once formed a neat house, was the unseen arc of whining shells aimed at a city across the river. A dull glow warmed the dark shadows of the room, turned the white faces gleaming with sweat and streaked with black to bright copper.

“First the tanks, then the flame-throwers, then the mopping-up parties,” one man said.

Another nodded wearily. “No more shelling now, anyway.” He sounded almost hopeful.

A third soldier, sitting beside the two wounded men, examined his rifle carefully and adjusted the bayonet once more. He looked up to catch the eyes of a comrade watching him.

“I know” he said savagely. “I know, for God’s sake. But it’s all I’ve got. How the hell do they think we can stop tanks with a bayonet? Why the devil don’t they send us the reinforcements we asked for?”

The man’s outburst was the sign for the officer to rise and walk towards the window. His movement silenced the oaths behind him into an indistinct mumble. Well, why don’t they send something? Why in all hell don’t they? He looked up at the gunner.

“Nothing out there as yet, Captain,” the gunner said.

The officer nodded. He climbed heavily onto the solid table which had been jammed with heavy beams against the window to support the gun. Standing there, his head close against the wall, his neck twisted forward, his eyes above the pavement’s level, he could see as far as the haphazard pile of concrete blocks which straddled the street. By this time the Germans must have occupied the remains of the houses beyond that freak barricade. But the snipers he had posted near there this afternoon were still silent. The man lying on the half-ruined ledge above the cafe’s entrance was still silent. There was nothing out there as yet. He wiped away the sweat which blinded him, streaking his face with his grimy hands. His fingers scraped over the heavy stubble on his jaw and rested on his chin. Five days’ beard, two days’ hunger and sleeplessness, a handful of ammunition, a spoonful of water in the last twelve hours. So we’ve come to this, he thought; we are fighting like rats from a basement. His bitter eyes followed the broken line of buildings which fenced the street. They rested on the pitted surface of the road. If only we had some petrol, he thought once more. Even one bottle of petrol.

“Nothing there,” he said abruptly. He knew that the man beside him and the men behind him were watching him. They were waiting for orders, for a last word of encouragement, and suddenly his bitterness turned to anger: anger with them for depending on him, anger with himself for his uselessness. They had relied on him for four weeks now, and he had brought them to this. Caught like rats, fighting like rats with bare teeth. Yet what else should he have done? At what point in the last four weeks could he have made another decision which would not have led to this? It seemed laughable now that he should have been so proud of the way in which he had led his men to Warsaw. After the slaughter-fields of Poznan, after the scattering and encirclement of the remaining armies, Warsaw had seemed the one hope. There men could make a stand and fight, men could hold the Germans until help came. Well, they had held the Germans. The Germans hadn’t been able to cross the Vistula, not with all their planes and tanks and ammunition, not with all their ten divisions in a tight noose round the city’s neck. Ten divisions… He stared at the house opposite the cafe. There Cadet Kurylo waited with the other machine-gun and five men. Four snipers. One outpost. Nine men here. Twenty altogether. A nice round figure. Twenty of them, and only four of his original command. He had brought them to this. His sense of failure was so complete that the whole catastrophe became his personal fault.

He turned quickly away from the window and stumbled down from the table. He faced the waiting men. Now was the time for a neat little speech; now was the time to tell them that everything would be all right. All they had to do was to hold this basement for one more hour, and then the trenches guarding the approach to the Poniatowski Bridge would be reinforced, and they could fall back to join their comrades evacuating the other streets, and together they would fight along the Vistula.

He steadied his voice and said, “Well, we know what we’ve to do.” A traditional beginning. Excellent. Wonderful. His voice grew more bitter as he gave the final instructions which were demanded of him: “…hold your fire until the

tanks ——” He halted. If he could see what was beyond

all this for these men he could face them more easily. What the devil was wrong with him, anyway? All he could see was the last round of ammunition and the eventual capitulation. Capitulation. The muscles in his throat knotted when he thought of the word, as if some one had stuck a knife into his side. Capitulation. He kept repeating the unbelievable word, twisting the knife cruelly in his wound.

He stared at the men, waiting so patiently in their exhaustion. Michal Olszak had been right, he thought. Two nights ago he wouldn’t let himself believe Olszak. Two nights ago he had insisted that a break-through could still be made, and to prove it he had tried it with some four hundred men. And of these four hundred… He said roughly, in sudden fury at himself and all the world, “Repeat tactics of this morning.” But this morning they had had grenades and petrol and phosphorus. This morning their numbers had been three times as great. This morning they had had a well-built shelter and a field-telephone and another machine-gun. And these men knew all that as well as he did.

The soldier who had been so preoccupied with fixing his bayonet gave a slow grin. “Kill what we can. We’ll give as good as we get, Captain.”

“Aye, Zygmunt,” one of the wounded men said, “the more we kill, the less left for some one else to kill.”

The captain’s tight face relaxed. He reached into his pocket and fumbled for the last cigarettes. He looked at them, crumpled and flattened in his blackened palm. “Three,” he said, his voice even once more. “If we cut them up they’ll go round.” What the devil had been wrong with him? he wondered again. His anger had given way to shame that he had doubted the men. They’d go with him all the way.

He found himself saying, very quietly, very slowly, “There will have to be a capitulation, of course. There’s no hope now of connecting with the outside world. This whole sector has just a few more hours’ ammunition left. But before then ——” He halted abruptly. He had said more than he should

have. Two days ago he would have cursed an officer who had let himself speak so frankly. Before then, he had been about to say, before then we have a job to do. But he hadn’t said it, and he wouldn’t. In this desperate moment men had a right to choose whether they lived or died. He waited tensely for their reply.

One of the men, the civilian with the armlet to prove he was a soldier, said thickly, “There’s no such thing as capitulation.” The lines round the officer’s mouth slackened.

Zygmunt, one of his four remaining cavalry men, was watching him fixedly.

“Yes, Captain,” he was saying, “well take a few of those Szwaby along with us when we go.” He looked as if he wanted to add, “What were you afraid of, Captain? That we’d go out to meet them with a white cloth waving above our heads?” Instead he grinned. It was a slow, wide grin, showing strong teeth against his ugly, blackened face.

Captain Adam Wisniewski smiled as he dropped the last fraction of his piece of cigarette on to the broken floor. Looking at the faces circling him, he was happier than he had been all this day. His smile broadened. He felt less like a man who has condemned others to death together with himself.

From the window the gunner’s voice ended the feeling of suspended time.

“Movement from the German end of the street,” he reported crisply. “And something’s been moving at the other end, too.”

Adam Wisniewski returned to the window. Once more he stared into the red-lined shadows of the street. “Machine-gun nests, probably.” He listened carefully, trying to catch the sounds of this particular street against the dull roar of battle. But the snipers were obeying orders, however much their fingers itched on the trigger. The angry chatter of German machine-guns swept the street, but there was no reply. The machine-guns ceased.

“They’ll think we all got killed in that shelling this afternoon,” the gunner said.

Wisniewski nodded. All the worse for them, he thought, when they do make up their minds to attack. Each of our bullets will have double value.

“Why don’t they attack and get it over?” the civilian with the armlet said angrily.

But the captain was staring at the western end of the street. He could see nothing. “Sure you saw a movement there?”

“Yes, sir. Jozef up on the ledge saw them first. He gave me the signal. Two men at least. Perhaps they are ours. About time some more ammunition was coming up. Unless they’ve forgotten us.”

“If they have ammunition they’ll send it,” his captain answered. Perhaps they are ours, he was thinking. Or perhaps the Germans have forced their way along a neighbouring street and are setting up machine-guns in the rear. Encirclement — that was all he could think of nowadays.

“How far away?” he asked.

“Less than eighty yards. More like sixty. Just ahead of that church which is burning.”

Adam Wisniewski jumped down from the table. The tiredness had lifted from his muscles. There’s another hour’s life in them yet, he thought. His eyes rested naturally on Zygmunt. And Zygmunt, just as naturally, had already risen to his feet and was moving towards the doorway.

“The usual, rotmistrz?”

Adam nodded, and watched the large, solid shoulders crouch to slide through the hole in the café’s western wall. Good man, Zygmunt. He met you half-way. The use of the word ‘rotmistrz‘ twisted Wisniewski’s tight lips into a bitter line. A fine captain of the cavalry he made now, he thought, and turned to the civilian with the armlet and two other soldiers.

“Time to get along behind our snipers. About fifty yards to the east. Each of you choose four possible places to work from, as you did this morning. Hold your fire until the attack comes. You know what to aim for.”

“Yes, sir.”

The civilian said, “Still don’t see why they haven’t attacked. Rather funny when you think of them trying to clear the street for a column of tanks to sweep through, when one tank and a couple of flame-throwers would finish us completely.”

Wisniewski looked wearily at the man. “Yes,” he admitted, “it’s rather funny.” The Germans were playing a clever game. Its shape was still vague, but it was clever. He added quickly. “And it’s funny, too, to hear us talking, when we could be getting into position.”

“Yes, sir.” The man with the armlet followed the others quickly through the jagged slit in the wall.

“And blacken your helmets and bayonets,” the captain shouted after them. God, he thought, sometimes I feel like a nursemaid. He posted a soldier to watch for Zygmunt’s return. The gunner was on the alert at the window. Jozef on his ledge would be lying still, watching, waiting. The two wounded men were propped against the bar. One of them only would be of any use. When Zygmunt got back that would make five men here. He looked at the less severely wounded man. Four and a half, he thought, as he picked up the other one’s rifle and secured its bayonet. His eyes travelled round the room once more. “Rotmistrz” he thought again; and he smiled grimly as he kept his eyes on his watch.

At the end of six minutes the sentry at the western wall gave warning. “Zygmunt. Two men. Civilians. Carrying something.”

Civilians, and only two of them. No reinforcements, then. Wisniewski cursed silently.

“Good,” he said briskly. He climbed up beside the gunner and watched the German end of the street.

Behind him Zygmunt’s voice exclaimed, “We’ve a chance now, rotmistrz! Eight grenades. A couple of bottles of petrol. Phosphorus. Rotmistrz!”

Adam turned away from the window. No reinforcements. He faced the two men who had come with Zygmunt. They were resting on the ground, their breath coming in heavy stabs. Then the younger of them walked unsteadily towards the box which they had dragged here with so much difficulty. “It isn’t much, I’m afraid,” he said in his precise voice. The pride on his thin face hesitated as he blinked nervously through his spectacles at the silent captain.

“It’s what we needed,” Adam said, and watched the smile return to the boy’s white face. A student, Adam thought, probably rejected for military service. He smiled too, and said, “Excellent!” Eight grenades. Two bottles of petrol. Well, that was something. “Excellent,” he said again, and this time he meant it.

The young man was talking on and on. “Left the car at the foot of the street when that machine-gun started. Didn’t know the Germans were so near.”

But Adam was no longer paying attention either to him or to Zygmunt, who was ripping up the last piece of his shirt into shreds. Loosely plaited, soaked with phosphorus, jammed into the narrow necks of the petrol bottles, they would serve as a fuse. Wisniewski stared now at the other newcomer.

“Just what the devil are you doing here?”

Michal Olszak took his pince-nez out of his pocket, wiped them carefully on his sleeve, and men settled them on the thin bridge of his nose. “I wanted to see you. This was the only way to come, as combined ammunition-carrier and dispatch-rider. I bring you some orders from Sierakowski.”

“You’ve come from Sectional Headquarters? What’s new? We’ve had no direct communication with them since that barrage smashed everything this afternoon.”

“They are trying to establish a field-telephone at the end of the street now. Your orders are to gather your men together and withdraw to that point. The Germans have begun a serious attack on the main road leading to the bridge. Sierakowski is of the opinion that if you don’t get your men back to the junction of this street and the main road, then you are in danger of encirclement. Besides, you may be needed back there to help in the defence of the main road.”

Adam didn’t speak. He sat down on the ground beside Olszak. He passed his hands over his eyes as if to wipe the sleep out of them. It wasn’t as simple as all that, he kept thinking. It wasn’t so simple. If only the telephone wires hadn’t been blasted away he could have talked to Sierakowski, could have persuaded him.

He said, “Did the man I sent to Sierakowski this evening get through?”

“Yes. Wounded badly. But he got through.”

“And Sierakowski isn’t sending us reinforcements?”

“He’s sending them to the main road. That’s where the attack has come.”

Wisniewski smothered an oath. It isn’t as simple as this, he thought again.

Olszak was watching him keenly. “I wanted to see you,” he repeated. “I thought you might have now changed your mind about that job. Have you?”

Wisniewski raised his head. He returned Olszak’s look. “No,” he said at last.

The blank look of amazement spread across Olszak’s face. When he spoke his voice was angry, sarcastic. “Still believe in no capitulation?” I’ve been mistaken, he thought, as his cold eyes rested on the younger man. His disappointment increased as his amazement ended. He tried to think of something to say which would cut through this young fool’s stubborn pride, but his chagrin was too great to let him speak. May he rot in his own blindness, Olszak thought savagely. If he couldn’t rid himself of that, then he was of no use. Not with all the qualities of courage and honesty and energy in the world would this young man be of any use. Olszak rose to his feet. It was particularly bitter that he should have always prided himself most on his ability to judge essential character.

“No,” Adam Wisniewski said again. “There will be a capitulation.” He paused and then said slowly, quietly, “You were right.”

Olszak’s anger gave way to further amazement. He sat down once more and wiped his brow. “You shouldn’t speak in such riddles. It’s bad for my temper.” He was looking at the younger man once more, and he knew how much such an admission must have cost Wisniewski. You were right. Two nights ago, when Olszak had spoken of capitulation, of continuing the fight by guerrilla warfare, Wisniewski, by violently denying the possibility of one, had refused the other. But now that he admitted the possibility of capitulation, why did he still refuse the task of forming a guerrilla force? And then, still watching Wisniewski’s face, he guessed the reason.

Olszak said, “Two nights ago you refused because you thought it was wrong. Now you refuse because you found you were wrong. You don’t trust yourself any more. Why don’t you leave that decision to me? Why blame yourself? There was no chance of success.”

So Olszak had heard about the failure of the break-through. Well, that saved some explaining. ‘Thank you,” Wisniewski said with over-politeness. His voice hardened. “Ninety-five per cent. of my men lost. That’s a franker way to state the case.” He rose and walked towards the window.

“It was a miracle that the five per cent. did get back,” Olszak said as he rose and followed him.

“All quiet, sir,” the gunner was reporting. “Can’t make head or tail of this. Can you, sir?”

“Don’t worry. They are coming soon enough,” Wisniewski said. “Keep your ears open for any signal from our snipers.”

“Yes, sir!”

Olszak said too casually, “Surely five per cent. could have slipped though. Why did you bring them back?”

“A few men wouldn’t have formed a break-through.” The younger man’s voice was tired, as if he were weary of explaining that to himself. Yes, some of the five per cent. could have slipped through, but that wouldn’t have been a fighting wedge. That would have been merely escape, and escape didn’t help those who were left behind.

“No,” agreed Olszak. So you came back, he thought. To this hell. Admitting defeat. His thin, neat hand rested on Adam’s arm.

‘Time enough to escape when there is nothing left to fight with,” Adam Wisniewski said roughly. But he didn’t shake off the other’s hand. He nodded to the red sky, smoke-streaked, above their heads. And his eyes turned towards the direction of the Vistula. “And we needn’t be sorry for ourselves. These are the people I’m sorry for, Olszak. You and I are trained for fighting. These civilians aren’t. They are the ones who suffer most.”

From the street, so strangely silent amid the uproar of destruction to the north and to the west, there came three sudden shots, evenly spaced. Adam Wisniewski’s hand tightened on Olszak’s arm, gripped it as if pleading for silence. The machine-guns’ angry chatter began once more.

“Damnation — it wasn’t so simple,” Wisniewski burst out. “It wasn’t so simple — damnation.” Over his shoulder he shouted, “These bottles ready, Zygmunt? Take a couple of grenades. Two for me. Leave the rest here. Quick.” He motioned the less seriously wounded man to stand by the gunner. To the sentry at the gap in the wall he gave last instructions about the grenades, about signalling Cadet Kurylo and his men on the opposite side of the street. In fifty seconds the dejected room was an alert battle-station.

Olszak said, “Anything I can… ?”

“Get back to Sierakowski or the nearest field-telephone. The frontal assault on the main road is only half the attack. The Germans are about to send a column of tanks through this street. If they carry it they’ll outflank the main road. Tell him to reinforce the junction of this street and the main road. We’ll try to delay the tanks until his men are in position. Half an hour. That’s the most we can promise.”

“But how do you know?”

“I didn’t. Not until the snipers gave us the warning. I could only guess. This afternoon this street was blasted by artillery. Since then — nothing, except machine-gun fire to try and draw us out. An hour ago I went up towards the German end of the street. They were digging. Clearing away. The street at their end had been blocked by ruins which were practically tank-traps. Now a sniper has given us warning that he has seen tanks being moved up to enter this street.”

“Then retreat to the end of this street. Face them there with reinforcements.”

“No. Once they really start moving they are hard to stop. The place to face them is up here. Just at that part of the street where it is narrowest, where it twists, just where they will think they have got free of these blocks of cement.” He turned towards the gap in the wall where Zygmunt waited impatiently. “Better reach Sierakowski,” he said to Olszak. “We can’t stop them permanently. We can only delay them for a little.”

“And what about that job I wanted you to do?”

Adam Wisniewski was placing the two grenades in his pockets. Like Zygmunt, he held a bottle of petrol with its phosphorus-soaked cork in his arm.

“Better wait and see how far I am wrong this time.”

Olszak’s thin lips smiled. “The meeting is to-morrow. Usual place. At the same time. Remember?”

“I hadn’t forgotten.” There was an answering smile. There was a touch of the old Adam Wisniewski as he pulled his helmet over one eye. The weariness had gone from his face, the stiffness from his body, as he bent to step through the gap in the wall.

Olszak watched the crouching figure, grenades in his pockets, petrol-bottle cradled in one arm, the borrowed rifle slung over his shoulder, reach the impatient Zygmunt. They knelt for a moment by a shell-hole, smothering their helmets and covering their bayonets with a coating of mud. And then the two men, doubling low, were circling round like hunters towards the German end of the street.

“Come on,” Olszak said to the very tall, very young man who had come with him here. He removed his pince-nez and placed them carefully in his breast-pocket. “Quick.”

“What about this wounded man? We ought to take him back.”

“Later. Come on.”

The other followed unwillingly. “But ——” he began.

“Come on.” Olszak was already through the informal door. He crouched as Wisniewski had done, choosing each available patch of cover with a quick eye and determined pace.

“I didn’t mean to overhear you,” the young man was saying as he caught up with Olszak, “but don’t you think he is mad? An attack through this narrow street, where there is only machine-gun fire? The Germans can’t be taking this street seriously.”

“Shut up and come on,” Olszak said angrily. “If we get separated run for that outpost and field-telephone near where we left the car. You know what to tell them. Seemingly.”

That silenced his companion. Even at the field-telephone he offered no addition to Olszak’s quick sentences.

“Well, I only hope he is right. That’s all,” he ventured as they at last reached their abandoned car.

The first explosion answered him. The ground danced beneath their feet. Olszak looked at the other man as they picked themselves up. This time he didn’t need to say anything.

Adam Wisniewski squirmed round the last block of cement which separated him from the road. Twenty yards away Zygmunt would be crawling forward, too, under cover of a broken wall. By this time Cadet Kurylo should have received the final signal: two of his sharpshooters would now be stationed as far forward as the other snipers, and the nose of his machine-gun would be pointing to cross-fire with the gun in the Café Kosciusko. The snipers were picking their shots carefully, enough to distract the Germans’ attention, yet not enough to destroy the Germans’ belief that this abandoned street was theirs for the taking. Adam Wisniewski listened to the savage machine-gun fire replying to the single shots. He thought of his seven men, crouching in the ruins of the street, shooting, eluding, changing positions. He was listening now to see if their firing power had been diminished. Six now instead of seven? Five or four? The shots were fewer, farther spaced. His men were silent now. Were they obeying orders, or had they in fact been wiped out? The machine-guns, seemingly satisfied, had fallen silent too. In this desert of jagged stone and powdered brick Adam waited. Desperation was in his heart. And then, out of the background of harsh noise, came a definite sound. It grew louder, focusing itself on this street. The first tanks were approaching.

He kept his head low and waited. At least he thought, it looked now as if the snipers hadn’t been killed. It looked now as if they had been following instructions; some of them, anyway. Sweat, as intense as his relief, lay cold on his brow.

The noise of the tanks ground nearer. He tightened his grip on his box of matches, if only to steady the sudden treacherous trembling of his hand. His stomach was caught in nausea. He swallowed painfully and drew his arm across his eyes to wipe away the sweat. The waiting moments always got him this way. The waiting moments were the worst. Once he started action, once he saw the tanks, he’d forget all these fears and worries. He’d only remember then. He had a lot to remember. These damned murdering swine. He’d remember.

The first tank was edging its way cautiously past the ruined walls of the houses. Once it cleared that narrowed piece of street it would be less skittish. It would increase speed. Let it. Kurylo and the gunner in the café would know how to deal with it when it was isolated. For it wouldn’t be followed by the row of tanks which it now led so arrogantly. The second tank was his. The third was Zygmunt’s. At this narrow part of the street two flaming tanks would hold up the traffic. Long enough. Long enough for Olszak to give his warning. And then the snipers would know what to do. They all knew what to do. God give them accuracy and timing.

Then he saw the first tank, nosing slowly into the street in front of him like a lumbering monster out of a hideous underworld. He raised his body slowly to free his shoulders. His fingers were on the pin of a grenade as the tank gathered speed. The second tank followed. He pulled out the pin, counting. His arm followed through in a careful arc. I’ve missed, too late. I’ve missed, he thought with growing desperation. And then the grenade exploded under the tank’s tracks. The huge bulk swung round to face him as its direction was lost. It twisted uneasily and then lay helplessly across the narrow street. A sniper was shooting to distract attention. Another sniper joined in. The cupped match in Wisniewski’s hands spluttered against the phosphorus cork. This time he threw quickly, aiming for the tank’s waist where body and turret met. He saw the bottle gleaming strangely in the phosphorus light as it landed safely. And accurately enough. He flattened himself tightly against the earth as the explosion’s hot blast scorched his neck and hands. All his breath was smashed out of him as the air current lifted him a few inches off the ground and then dropped him. The massive block of concrete beside him trembled, and then against its other side he heard the sharp hail of machine-gun bullets. He couldn’t even allow himself the pleasure of looking at the flaming tank. Here was one that no more would grind horse and human flesh into pulp. He began to crawl backwards, away from its blistering heat and sickly smell, away from the fireworks of its ammunition. As he reached the cover of ruins farther back from the road he was thrown on his face once more. Zygmunt had aimed his petrol-bottle well.

Wisniewski found he was shouting. How long he had been shouting was something he didn’t know, and what he was shouting didn’t make sense. He stopped suddenly, and then laughed at his caution. No one could hear him. Not in this inferno of sound. All he had to worry about now was a German machine-gunner or a German sniper. Or a shell. They were using trench mortars again. There was an explosion behind him, and a wall to his right crumbled as a shell’s fragment ploughed into it. He picked himself up again and his rifle held ready, ran for new cover. That shell had been aimed at the large block of cement behind which he had sheltered as he waited the tanks. The Germans didn’t take long, he thought savagely. Well, even they weren’t infallible. This was one time they hadn’t been so clever. A handful of men had deluded them. A handful of men… He felt better when he discovered that thought. He felt so much better that, crouching under the rim of a shell-hole, he was surprised to find that the spreading stain on the shoulder of his tunic was not oil but blood.

From where he lay he could see two columns of flame from the street. He wondered where Zygmunt was now, where the others were. Probably crouching into holes in the ground like himself, waiting as he was for this sudden barrage to spend its temper before they could make their way back to the Polish lines. His fingers touched the wet stain on his tunic. Nothing serious, not serious enough to prevent him from reaching the Vistula. Nothing was going to prevent him now from doing that. Not now. To-morrow was the meeting day. To-morrow he could give Olszak his answer. He edged cautiously out of the shell-hole and began his slow journey back to the Café Kosciusko. In front of him the sky over Warsaw was bright red.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”