The Fugitives (18)

By:

September 20, 2014

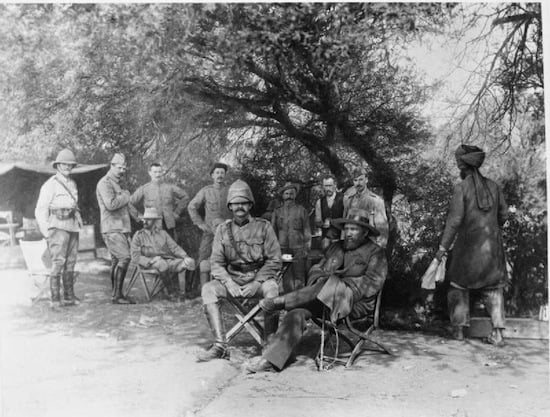

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Morley Roberts’s 1900 novel The Fugitives, an adventure set against the backdrop of the Second Boer War (1899–1902). The author was once known for his novel The Private Life of Henry Maitland (1912), but he quickly passed into obscurity. How obscure? In a 1966 story about plagiarism (“The Longest Science-Fiction Story Ever Told”), Arthur C. Clarke attributed an 1898 sci-fi story of Roberts’s (“The Anticipator”) about the same topic to H.G. Wells; in a 1967 guest editorial in If (“Herbert George Morley Roberts Wells, Esq.”), a contrite Clarke noted that not a single Morley fan had emerged to point out this error. HiLoBooks — in conjunction with the Save the Adventure book club, which under the editorship of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn is issuing The Fugitives as an e-book — is rectifying this situation. Enjoy!

“You hear thunder!” said Hardy. He meant it in the contemptuous American sense, for he did not see how Blake could hear anything when there was no likelihood of there being any fighting north of Kimberley. But Blake took the “thunder” literally.

“No, I hear guns,” he repeated.

And Hardy lay down by him and put his ear close to the baked earth. He certainly heard nothing, and said so.

“Well, it was very faint,” acknowledged Blake, “but I feel certain I heard them. Or, at least, I did feel certain.”

Now he was not sure, and Hardy, who was accustomed to trust his own senses, declared that he must have been deceived.

“You don’t think you could hear an engagement a hundred miles off, do you?” he asked.

Blake declined to commit himself, but on the whole he did not see why not.

“In any case we know they must be fighting there,” he said.

“And naturally in your strained nervous condition you would imagine you heard firing,” answered Hardy. “Keep cool or you will break down, and I shan’t get you home to England after all my trouble.”

Blake sat up very suddenly and stared at Hardy with a most curious expression.

“By Jove, I do think I must be mad,” he said. “Do you know ——”

“What?” asked Gordon quickly.

“Do you think I’m going back home? Why, you must be mad too. Of course I’m going back to duty.”

It was undoubtedly the first time that the truth occurred to either of them, absurd and unlikely as it may seem. Hardy had been possessed from the very first with the notion that he had to bring Blake back to England. Gwen had said so, and what Gwen said was to be done. And Blake, after a strain of prison which had told upon him in a hundred subtle ways that only skilful professional watching could have detected, had been living in an absurd dream about the girl in England who, as Hardy had said, was in such despair about him. His duty lay with her. His captivity had taken him out of the war. What was it to him? And now, at the very imagination of the thunder of war, he awoke suddenly.

“Of course I’m going back to duty. I must report myself to the first lot we fall in with,” he said, with dilated eyes.

“And Clare?”

“Oh, damn,” said Blake.

He got up and walked about.

“You — we — that is — must send her word that it is all well.”

“But it mayn’t be well — in England.”

Blake burst into a blazing rage and cursed Hardy furiously.

“Don’t talk to me; let me be!”

He threw himself down, and not another word was spoken for an hour.

“Oh, my God, have we to wait all the day, all the day?” groaned Blake at last.

“I don’t care a hang,” said Hardy gently; “my dear chap, if you don’t mind risking going back the way we came I’ll travel by day.”

Of course Blake said nothing. But when Hardy went to sleep a little later, he sat up and stared across the veldt, then shimmering under the blazing sun.

“Horses, — if we only had horses,” he kept on saying to himself. “If I were alone I couldn’t keep my hands off any Boer I saw with one.”

The strain of the awakening to the fact that Clare would have to fight her own fight without any help from him was now very visible upon him. It came as a last straw, and if it did not break down his sanity it at any rate came near it. In spite of the glaring sun his pupils were still a little dilated and he found the light trying.

“What’s wrong with my eyes?” he asked angrily. “Oh, Clare, Clare!”

He fancied he heard a noise a little north and west of him and lay down at once, and, with his hat drawn over his brows, watched eagerly.

“I wonder who it is?”

His senses were indeed abnormally and morbidly keen. The noise he heard was a long way off, and this time it was not guns. It was made by six mules drawing a four-wheeled Boer buggy. He saw it come round a bend in the river, and the next moment it was in full sight. Blake grinned.

“That’s what we want!”

There were two Boers in it.

“What a pity it isn’t night,” said Blake. “Or if I had a rifle.”

It looked at one moment as if the buggy was going down the Hoopstadt-Boshof road, but in a few minutes Blake saw the men were going toward Bultfontein.

“I daresay they are taking despatches,” he said. And he lay very low, like a scared lizard on a rock.

“If I had a rifle,” he muttered again.

And then the vehicle stopped within forty yards of him. He saw the men were looking toward the river. Presently one of them got out, and, taking a big water-bottle, came right toward the low bank of the Vet where Hardy was lying. To reach the river he had to pass Blake, who was hidden behind a rock and some willow scrub.

“I’ll have you,” said Blake, chuckling. “Damme, I’ll have you!”

He took no account of the risks, for his genius of good advice was fast asleep. Nor had he any clear notion of what he was going to do. His brain was working very furiously, and he kept on chuckling in an uncanny way which was not very healthy. The Boer, who was a man of nearly fifty, would not have felt very comfortable had he seen his enemy’s eyes. But Blake let him pass, let him climb down the bank, and then slid from his hiding-place and followed him. He was not a yard behind him when he saw the man stop. He had caught sight of Hardy sleeping. The next moment Blake gave a tremendous jump, landed right on the Boer’s back, and, as they fell headlong upon Hardy, he got his fingers about the man’s throat. Neither of them uttered a sound, but just as they were falling Hardy awoke. The next moment the overthrown Boer struck Hardy on the head with his own head, and the triumphant but nearly mad Blake had two insensible men to deal with.

“I did it,” said Blake in a whisper. “By Jove, I did it.” And he shook Hardy savagely.

“Come, wake up!”

But Hardy could not wake, and was not likely to do so for some minutes, even if he did then.

“Very well, I’ll finish it myself,” said Blake; and now his brain cleared wonderfully, and he smiled and went about his task with the cunning of the very devil. He filled the big water-bottle, spilled a pint over Hardy’s head, and then, laying the bottle down, stripped the Boer’s coat off. He put it on instead of his own, and with his handkerchief tied the prisoner’s hands. He then took Hardy’s Mauser pistol, and, with the Boer’s hat slouched over his face, carried the water back to the waiting buggy. The Boer in it never even turned round. He said something in Dutch as Blake got to the back of the cart. The two rifles belonging to the men were leaning against the seat behind the driver. Blake coolly reached for them and threw them on the veldt, and when the driver at last did turn round he found the muzzle of the Mauser pistol held straight on him.

“Mein Gott!” said the Boer.

“Can you speak English?”

“Yes,” replied the Boer very hurriedly and with a gasp.

“Then get out and lie down,” said Blake. “I’m tired of walking. Now, mind you do as I tell you or I’ll kill you at once.”

There was not the slightest doubt in the Boer’s mind that this accursed rooinek, sprung from heaven alone knew where, was very much in earnest when he spoke. Some men’s words sometimes carry conviction at once. The Dutchman climbed from his seat and made no difficulty about lying flat upon his face while Blake tied his hands behind him.

“By Jove, won’t Hardy be surprised,” said Blake, laughing. “I wish he would come along.”

He called “Hardy — Hardy,” but there was no answer. Blake was slightly perplexed as to his next step. He did not dare leave the mules, for if they ran away it might be quite impossible to catch them again. After some little cogitation he took a couple of halters from under the seat of the buggy and knee-haltered the two leaders. As he did so the recumbent Boer plucked up enough spirit out of his vast surprise to speak to this apparition of a man.

“How did you come here, Englishman?” he asked.

“I walked,” said Blake, “and I took the train — from Pretoria.”

“From Pretoria! Almighty! are you an escaped prisoner?”

Blake admitted the fact.

“Have you killed the other man?” asked the Boer uneasily.

“Not by any means,” said Blake. “He’ll be all right directly. Now, I want you to answer a few questions.”

He came and stood over the prostrate Dutchman.

“Where were you going?”

“To Bultfontein.”

“So I thought,” said Blake, “and on to Bloemfontein?”

“Ya,” replied his new acquaintance.

“How are things going? Have your people taken Kimberley yet?”

“It will surrender this week,” said the Boer.

“I think not,” said Blake. “Have you heard where our new Commander-in-Chief is now?”

“He was on the Modder, but we heard he had gone again to Colesberg.”

“Speak the truth,” said Blake ferociously.

“Almighty! it is God’s own truth,” replied the prisoner in alarm.

Blake reflected a minute, and came to the natural-enough conclusion that what the Boers thought was not altogether likely to be true.

“And your Cronje is still at Magersfontein?”

“He is there.”

Blake thought aloud.

“I don’t believe that Bobs is at Colesberg,” he said, and as he said it the Boer protested, and Blake bade him be quiet.

“Is there a commando at Boshof?” he asked.

“I suppose there may be,” replied the Boer sulkily, “but I don’t know.”

Blake saw that there was little likelihood of Boers being there in any force unless the Magersfontein position had been stormed or turned. So far nothing had been said that made him think that going straight for the Modder, far east of the Kimberley railway, would be especially dangerous.

“Get on your feet,” he said, and he took two more halters from the buggy.

By now Hardy had come up out of the depths of unconsciousness and found himself lying close to an entire stranger. But the crack upon his head had produced a certain amount of concussion of the brain, and he was in a singularly poor frame of mind for solving any problem. He could not recollect how he came where he was, and did not remember in the least how he had been awakened. As he sat up, the pinioned Boer moved, groaned a little, and opened his eyes. Hardy blinked at him and saw how he was tied. Seeing this suggested to Hardy that the man should be released, and he was just engaged in pulling at the knots when Blake, with the other prisoner, came down the bank.

“Here, what are you doing?” said Blake. “Stop it, you infernal ass!”

Hardy resented this very much, but he stopped all the same.

“Why not?” he asked stupidly.

But Blake was excited and dominant, and in his next moves showed an astounding ingenuity which he could never have displayed in a state less near insanity.

“All right, you sit still,” he said to Hardy; “you are stunned, I know. I’ve taken these two men and got their mules and their old trap. It’s our turn to go riding after I have fixed these men up.”

What he said was the merest moonshine to Hardy, who was now conscious of very little but a splitting headache. He watched Blake with fanciful curiosity, but did not care in the very least what he did.

“All right, I’ll tie you two up,” said Blake. He made the man whom he had brought sit down with his legs on each side of a willow sapling.

“Now you stop so,” said Blake, chuckling. He went to the other Boer, who had now recovered consciousness, and made him take a similar position on the other side of another little sapling about four feet away from the first. Taking a halter he lashed the two men’s ankles together, and did it without much mercy and without paying the least attention to their remonstrances.

He looked down on his work with pride.

“How’s that, Hardy?” he asked triumphantly. “I’ll bet they won’t run after us now. Come on, old man.”

“Are you leaving us to die of hunger and thirst?” asked the Boer who had been driving.

“Not at all,” said Blake, with a chuckle. “I’ll leave you a bit of scoff and some water and untie your hands. And when it is night you can scream for assistance. They will most likely hear you at Hoopstadt.”

He was as good as his word, for, when he had planted Hardy and the two rifles safely in the cart, he came back with the food and water and then unlashed the men’s hands. He had fixed them up in such a diabolical way that neither of them could get his hands, even when loose, within eighteen inches of his ankles.

“Good-bye,” he said; “we’re going for you to Bultfontein.”

In spite of their entreaties he left them, and as he went he laughed. Assuredly he was not quite sane. Though he might have done exactly the same thing if he had been, he would have done it rather differently and would not have been so brutal.

He played the dominant role now, for during the next few hours Hardy was a child in his hands and was violently sick as the heat came down upon his head. He had no real sense of the astounding risks they were both taking. He sat huddled up in the bottom of the vehicle while Blake laughed and drove like the very devil. He had cut across the angle of the Bultfontein-Boshof road and was now on the latter, driving openly and without any concealment or notion of it. Just as openly he pulled up about noon by the side of a little vlei with some muddy water in it, and outspanned. Hardy got out, and, crawling under the buggy, fell fast asleep in the shade. He maintained afterwards that he was quite conscious, somewhere in his mind, that Blake must be nearly mad, but he was in the condition of a man whose temperature is about 106°. Nothing matters in the least.

But at three o’clock he woke up without any headache or any incapacity of mind except what the situation made him feel. He found Blake sitting in the sun, smoking and writing a letter to Clare. He looked up when Hardy came toward him.

“Well, this is better than walking,” said Blake, with what seemed obviously insane satisfaction. The shock was a very heavy one for his companion, for he naturally exaggerated a fit of strained temporary insanity, which after all was not so unnatural considering all Blake had gone through.

“We’ll go on directly I’ve finished this letter to Clare,” added Blake. “Don’t you think I was just as ‘slim’ as any Boer?”

Hardy looked up and down the road, and found to his relief that not a soul was in sight.

“But we’ll get off this road as soon as we can,” he thought. After looking at the rifles and seeing that they were loaded, he put on one of the two bandoliers of which Blake had stripped his prisoners, and, with the rifle slung over his shoulder, drove up the mules. He inspanned them without much difficulty, for Blake’s driving, which was always severely Irish, had taken the devil out of the rowdiest among them. He called to his companion, and after putting away the letter, Blake came.

“I’ll drive,” said Hardy.

But within five minutes trouble began, for he drove off the road and began to edge straight south.

“Here, what are you doing?” asked Blake. “Don’t you see you are off the road?”

“Of course I see, my dear chap,” replied Hardy, “but you surely don’t want us to keep to it any longer. We may run into a party of Boers any minute.”

Now, if there is one thing more than another which characterizes the kind of overstrain that Blake was suffering from, it is the belief of the insane person that he knows very much better about anything than anyone else possibly can.

“My dear chap,” said Blake with the oddest kind of irritable superiority, “you are not well. Please keep to the road. I’ll answer for it that we’re all right.”

“How the devil can you answer for it that we don’t come slap on a hundred of the enemy?” asked Hardy, with forced geniality. “Come now, Blake, if you’ll allow me to get off the road now, you shall drive on it as straight as you like when it gets dark.”

Blake got furious at once.

“I took this shandrydan,” he said, “and I’ll run it. If you don’t like it, get off and walk.”

This was really the most sensible advice he could have given his companion. But if Hardy had taken it he was sure that Blake would be a prisoner again long before night. He wondered for a minute whether it would be well to risk a struggle with a man who was — at any rate temporarily — quite insane. His doubts were resolved by finding that he had his pistol no longer in his own possession. As a matter of fact it was in Blake’s hand now.

“Very well, then, you can drive,” said Hardy, and he passed the reins over to Blake without a moment’s delay. The Irishman hesitated, but took them, and drove back to the Boshof road.

“All right, I’ll fix you,” thought Hardy as he reached over the seat and got a tin cup and the water-bottle. “I’ll fix you, my friend, and I’ll do you good at the same time.”

Without Blake’s observing it, Hardy took a little bottle of tabloids from his pocket, crushed some of them in his hand and dropped them into the cup. He poured in water and watched them dissolve.

“All right, give me a drink when you’ve done,” said Blake, and Hardy offered him the cup.

“After you,” said Blake, who was naturally polite and had some consideration for his deposed leader, who was, as he now imagined, of proved incapacity. This politeness very nearly put Hardy in an awkward situation. But as Blake suspected nothing he was able to set the drugged cup down and get another.

“We’ll drink together,” he said. “I daresay you are right after all, Blake.”

“Of course I am,” replied Blake, as he drank. “What you want is dash. These Boers are overrated men.”

Hardy watched him closely.

“These Boers are —— overrated —— men,” re peated Blake slowly.

He blinked hard and repeated it again.

“Are —— overrated —— over —— rated —— men.”

His head dropped with a jerk.

“I think you must be sleepy,” said Hardy, “you never had any sleep yesterday.”

“No,” drawled Blake, “I never —— had —— any —— yesterday.”

And with that he slid off the seat and fell in a heap. Hardy gripped the reins, pulled the team off the road, and sent them toward the nearest kopje, which was at least three miles southeast of them.

“Handy thing, morphine,” said Hardy. “I daresay he will be all right when he wakes up.”

But Blake slept like the dead as he drove, and when he finally pulled up in a little kloof at the foot of the flat-topped kopje, Hardy stretched the man out straight on the floor of the buggy and made him as comfortable as he could. He knee-haltered some of the mules, which soon discovered a small pan of rainwater and some grass. For the present there was little danger of discovery unless they were tracked by the wheel-marks, and it was quite possible that the two owners of the mules were still anchored on the banks of the Vet.

“We ought to be able to see Boshof,” said Hardy presently, and after he had had his smoke he climbed to the top of the hill, which was swarming with scorpions of course. Every rock he displaced had at least one wicked-looking brute under it, which sat still, held up his foreclaws, and had his tail ready to strike. From the summit he saw the shining galvanized iron roofs of Boshof some fifteen miles away. In that atmosphere the distance appeared nothing. Boshof was close at hand, and so were the distant kopjes away on the Modder and even as far as Aasvogel Kop toward Bloemfontein. The weather that day was not so hot; some heavy clouds piled themselves high above the distant Drakensbergs, and a light easterly wind cooled the plains, which seemed so utterly deserted. The atmosphere was infinitely transparent and invigorating. As Hardy lay flat and reconnoitred he was conscious of peculiar well-being. His headache had gone; he felt strong. The height and the air, which was so exhilarating, sharpened his senses. He saw some movement around Boshof, and far away to the south he knew that faint clouds close to the earth were clouds of dust. They were getting near the theatre of actual hostilities; those clouds meant mounted Boers moving. How could he tell that they did not mean British troops?

And then he heard something. At first the sound was no louder than the sounds made by a man’s heart beating as he listens. And then he remembered that Blake had talked of “guns.” In Blake’s condition, as Hardy knew, it was possible that the senses grew supernaturally keen.

“I do hear guns,” said Hardy. “It must be Kimberley. And Kimberley is sixty miles away.”

So, too, were the Modder drifts to the south of him. In spite of Blake’s acute diagnosis of the situation it did not occur to him that even now there might be actual fighting east of Kimberley, many miles up the Modder. But certainly he heard guns, and as certainly the sound seemed to come from the south, not from the southwest, where the Diamond City lay. Had he only known what was going on, three days’ hiding in that isolated kopje would have freed both from anxiety and sent them into the arms of British patrols advancing to the north of Boshof.

But he did not know that, and they had to endure much ere they learned it.

“How does the fight go? and what fight is it?” Hardy asked. “And here I am with some one who is, for the time, little better than a madman!”

He clambered down the scorpion-haunted hill and got back to camp.

It was close upon sundown when Blake awoke, and, to his companion’s intense relief, the man was at once saner and weaker. It took a long explanation to make him understand how they came by the buggy and the mules. But when it was explained he remembered it all.

“I hope the poor devils I tied up are all right,” he said. And so did Hardy, though to him all that portion of their adventure was no more than a dream.

Then the sun sank, and the shadows covered the veldt, and they inspanned the mules and started south.

“I heard guns to-day,” said Hardy.

“What did I tell you?” asked Blake. “Why am I so muzzy-headed, Hardy?”

But Hardy did not tell him about the morphine. He talked of everything that would soothe his companion as they drove with difficulty over the veldt, going at a walk. The moon now would have been of infinite use to them. But at one donga which interrupted them Hardy discovered a crossing, and, by the marks of wheels, knew he was going on something which a South African might have called a road. Sometimes they were able to trot and go fast. By an hour after dawn — for they ventured on that extra hour — they were only some ten or fifteen miles north of the Modder and well in sight of the Kimberley-Bloemfontein road which runs north of that river’s banks.

And all that long day they heard sounds of distant artillery. Sometimes they declared it was not so distant, that it came nearer and nearer.

“I tell you we have struck at their centre,” said Blake. “Now Cronje must look out.”

That afternoon, from the top of the kopje under which they were camped, Blake and Hardy saw a great cloud of dust miles away to the south and west.

“What is it?” asked Hardy.

But Blake did not know.

Yet in England they knew very soon afterwards that the British cavalry were in Kimberley, and that the Boers at Magersfontein could hardly escape. Had the two men who saw this cloud of dust rising like a pillar of fire against the westering sun known it, they would not have planned to drive south right into the issuing swarm of hornets, smoked out of their den at last.

* “Don’t you think I was just as ‘slim’ as any Boer?” — Afrikaans for “guile,” “sneaky,” “untruthful.” See this 1900 Harper’s Monthly essay on “The Boer ‘Slim’,” for example.

* “And your Cronje is still at Magersfontein?” — Piet Cronjé was a general of the South African Republic’s military forces during the Anglo-Boer wars of 1880-1881 and 1899-1902. During the Second Boer War Cronjé was general commanding in the western theatre of war. He began the sieges of Kimberley and Mafeking. At Mafeking, with a force between 2,000 and 6,000 he laid siege against 1,200 regular troops and militia under the command of Colonel Robert Baden-Powell. After Lord Methuen attempted to relieve the siege of Kimberley, Cronjé fought the Battle of Modder River on 28 November 1899, where the British won a Pyrrhic victory over the Boers. Cronjé’s novel tactics at the Modder River, where his infantry were positioned at the base of the hills instead of on them (in order to increase the effectiveness of their rifles’ flat trajectories) earned him a place in military history.

* “I took this shandrydan,” he said. — A small horse-drawn vehicle, also called a “governess cart.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”