King Goshawk (36)

By:

September 2, 2014

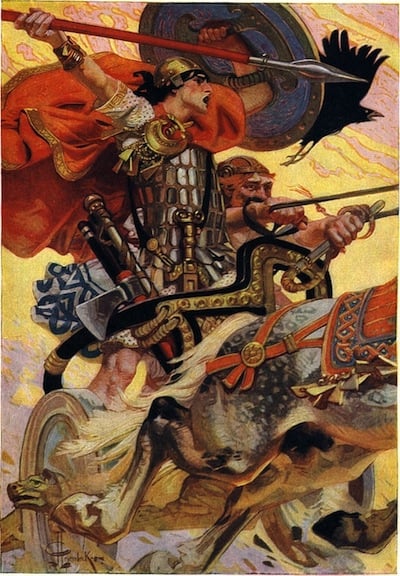

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 10: How Cuanduine began to Fall in England’s Estimation

By the esteem in which he was held, and by the feeling roused by his orations, Cuanduine judged that the time was now ripe to urge the immediate liberation of the song-birds and wild flowers from Goshawk’s control: to which effect he spoke at his next meeting. To his surprise the suggestion was received with coldness, and the applause when he sat down was of the most perfunctory character, and intermingled with not a few hisses. The Mammoth Press at once saw its opportunity, and next morning opened the campaign with characteristic headlines:

UNDILUTED SOSH

BLACKBIRDS AND BUTTERCUPS FOR EVERYBODY!!!

The leading paper of the group said:

Mr. Quandine’s latest effusion can only be described as a violent attack upon the rights of property and the freedom of the individual. It is nothing less than a proposal to tax the provident and efficient for the benefit of the thriftless and idle. Briefly, his policy is the forcible expropriation of the birds and wild flowers in private ownership and their transference to communal control, when their enjoyment will of course be permitted only on a dead level of equality. Mr. Quandine shows all the ignorance of human nature and indifference to the realities of life characteristic of the agitators’ breed. He apparently forgets, or pretends to forget, that tastes differ: that to listen for an hour to a thrush’s warbling might be torture to one man, and merely whet the appetite of another for more. Even leaving such extremes out of account, a regime under which every man, woman, and child would be compelled to listen to, say, three bird-songs, and smell, say, half-a-dozen wild flowers daily, would be absolutely intolerable in its appalling monotony.

Another said:

This anarchical proposal means the complete disorganisation of our whole social and economic system. What order or discipline is possible if the private is to have as many daisies as the colonel? if the man behind the counter is to enjoy the melody of the robin equally with his employer?

Another asked:

What incentive do we offer to industry and enterprise, if the financier or monopolist, at the end of a lifetime of toil, is to be allowed no more of melody and perfume than the tramp lying by the roadside?

And another cried:

If this wildcat scheme were put into practice it would drive capital out of this planet to Mars or Venus, or even out of the Solar System.

The Cumbersome Press was more mildly remonstrative. The Morning Journal said:

Mr. Cuanduine’s poetic imagery and moving eloquence were never better displayed than last night. He drew a beautiful and touching picture of a world in which every man and woman, whatsoever their condition or income, should enjoy the song of the birds and the perfume of flowers to their heart’s content. It was a delicate and tender fancy: but we must not mistake a poet’s dream for a practical possibility.

The Daily Sootherer said:

Mr. Quandine’s remarkable theories are interesting subjects for intellectual speculation; but they will not stand the test of practical application. How, for instance, is the distribution to be effected? Is every man, woman, and child, regardless of its age, capacities, and tastes, to be given, free, gratis, and for nothing, say three robins, two larks, and a dandelion? And how is this equality to be maintained? The very next day one person may lose one of his larks, another may want to sell his robins, a third will want to buy them. In a short time we should be back exactly where we are. The fact is that you cannot change human nature by act of Parliament; and few things are so deeply planted in human nature as the acquisitive instinct.

There were also two wretched little sheets which clung to a precarious independence outside the two great Combines. These, likewise, shot their bolts at Cuanduine. Said the Daily Trumpeter:

It is useless for elegant aristocrats like Mr. Coondine to talk academically about beauty and freedom. The time is gone by for palliative measures. Until all the birds and flowers are nationalised and managed by Government Departments, abuses like the present must continue.

And the Red Bonnet said:

The speeches of Mr. Quandine, though doubtless well intentioned, and not unfriendly to the toiling millions, only show how impossible it is for these dilettante artistic members of the bourgeoisie to grasp realities. The fundamental fact is that so long as there are birds and flowers at all they must inevitably accumulate in private hands, and the remedy is — Abolish them.

Cuanduine was filled with astonishment at this opposition, and overwhelmed by the arguments on which it was founded. Conceiving himself to be misunderstood, he delivered another speech in the same tenor, but using simpler language to explain his meaning, and replying exhaustively to each several criticism. He was listened to in obstinate silence; the applause was more formal than before, the hisses more distinguishable. The Mammoth papers redoubled the vigour of their attacks; whilst those of Lord Cumbersome, though they maintained stoutly that, judged purely as an artist, Cuanduine was one of the greatest men that England had ever produced, found it all the more necessary to outdo them in denunciation of his policy.

He spoke a third time to a half-empty theatre. With commendable patience he tried to answer a hundred silly or tipsy questioners. At the finish there was no applause at all.

Now amongst the multitude of his changing hearers there was one young woman that came to every meeting, and sat always in the front row, entranced by the beauty of his godlike countenance and by the grace and strength of his manly form. Her name was Ambrosine, a lovely and accomplished girl, that had been brought up on the intellectual novels and plays of the Edwardo-Georgian period — of course, in bottleggers’ editions at ten guineas a copy. She sat on now in the darkened auditorium watching the figure of Cuanduine leaning, deject and weary, against the chairman’s table on the deserted stage. Presently, rising from her seat, she went forward to the footlights and softly called his name.

Cuanduine looked up and saw her. “What?” said he. “Have I one listener left?” Then he leaped to the ground beside her, lightly as a cat. “Tell me,” he said, “why are the people fled? But yesterday my voice was music in their ears; my words carried them to ethereal regions. Now they will not hear me, and they begin to hate me. What have I done?”

“You have become a bore, Cuanduine,” replied the girl. “You have ceased to be an entertainer, and have become a man with a mission.”

“But my mission is for their benefit. My one desire is to restore the beauty that has been stolen from their lives.”

“A vain desire, Cuanduine. The people who are really robbed of the birds and flowers are too hungry and ill-clad to miss them. The others do not grudge the couple of shillings charged for entry to Goshawk’s show places. They do not go very often, you see.”

“And you?”

“I am rich, and go as often as I please. I spend most of my days there, feasting on melody and perfume, lost to the world, its sordidness and cruelty.”

“That must be very bad for you,” said Cuanduine.

“How so?”

“Beauty is no soothing drug. It is the salt of life. Taken otherwise it is a poison: it induces not sleep, but death.”

“If that is so,” said the girl, “I cannot help it. I cannot change the world: but neither can I live in it as it is.”

“I have seen that sorrow in your face,” said Cuanduine, “time after time, when you have sat in the front row at my meetings.”

“What?” said the girl joyfully. “Did you really see me? Did you single me out — just me — amongst your thousands of hearers?”

“Yes. The footlights illuminated your face.”

“Oh, don’t spoil it,” said Ambrosine. “Say that there was something you saw in me different from the rest: understanding, perhaps: sympathy, even. For I do understand and sympathise. Listen, Cuanduine, I am a woman of advanced views, and not afraid to speak what is in my mind. I love you, Cuanduine. I have loved you from the first moment I saw you.”

“What has that to do with the advancement of your views?” asked Cuanduine.

“Why, this: I believe that love should be free and unfettered, and should admit no bar to its expression.”

“Your ancestor, the Stonewoman, did not think that an advanced view,” said Cuanduine.

“I do not understand you,” replied Ambrosine.

“If you cannot understand that,” said Cuanduine, “you should not trust any of your beliefs so far as to act on them. There was a gentle maiden once that had never seen a lion, and knew no more of its habits than she might have gleaned from a picture and a chance saying that it was a noble beast. One day she paid a visit to a menagerie, and, seeing a lion pent up in a cage, her heart was wrung with pity, in so much that she besought the keeper to set it free, saying that it was a shame that so fine and generous a creature should be so trammelled. Then, as the keeper stirred not, ‘What, fellow,’ says she, ‘art thou a rude uncourteous boor, that thou refusest me this boon? or what fault dost find with my sentiments?” ‘Nay, madam, ’tis not your sentiments are at fault,’ quoth he, ‘but your zoology.’”

Ambrosine was fain to laugh, saying that Love was not a lion. “Nay, ’tis more dangerous,” said Cuanduine, “and will not bear playing with. But shall I argue with Beauty? No! If a kiss will stead you, here’s arms to leap to.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”