King Goshawk (32)

By:

August 6, 2014

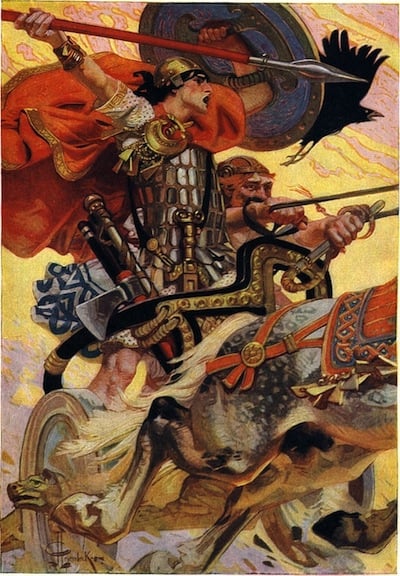

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 6: Cuanduine meets divers strange Persons

Having shaken off his guide, Cuanduine passed out of the city and came presently to a grove not far off, wherein an army of workmen had just finished erecting a hugh pyre of logs over tar-barrels. A hundred and fifty feet square it was at the base, and forty feet high, and it was overtopped by an earthen ramp over a mile in length. Just as Cuanduine arrived torches were put to the tar, and flames two hundred feet high shot up into the sky. Then up the ramp came a motor lorry heavily laden, which, when it reached the summit, was tilted back until there tumbled upon the flaming pyre an avalanche of hams and gammons of bacon, to the amount of nearly three and a half tons. What a sizzling there was as the flames fastened on this succulent feast, and what a divine odour. It was as if a fifteen-acre rasher were being fired for the breakfast of Zeus Olympicus, which, had he smelt it, would have provoked his mouth to watering the world with a second deluge. Then came a second lorry and emptied into the fire ten thousand or so long hundreds of eggs. But that sent forth a different savour, not quite so appetising: indeed, you would have thought the Plutonian cook was brewing a hell-broth of asafoetida for the supper of the legions of the damned. This was followed straight by other lorries, more than I can count, which shovelled on to the leaping flames a goodly holocaust of meat, butter, vegetables, groceries, wheat, oats, barley, flour, fruit (both fresh and preserved), fish, poultry, game, sweetmeats, biscuits, cheeses, and a thousand other sorts of provender, some packed in bales and boxes, but much of it loose and au naturel, until the mixture of smells was so foul that the stomach of Cuanduine could stand no more of it, and he was about to withdraw in search of a more salubrious climate, when he noticed a workman standing near, whom he approached and asked the meaning of this incineration.

“This is the Regional Destructor, sir,” said the workman, “where we destroy the surplus food, sir, to keep the prices up.”

“Why do you keep the prices up?” asked Cuanduine.

The workman took a handbook from his pocket and read: “Low prices depend on mass production. Mass production depends on unlimited capital. Capital requires a reasonable return for its outlay. Therefore the prices must be kept up. Q.E.D. Socialism is an economic fallacy.”

“This,” said Cuanduine, “seems to me the very sublimate of criminal folly.”

The workman gave him a look of incredulity not unmingled with horror. “What, sir?” said the honest fellow. “Do you speak like that of the inevitable laws of political economy? — you who are so well fed. Look at me. My children are all crippled with rickets because I cannot afford to give them butter, yet I see all this butter burnt without complaint. Why? Because I know that if it wasn’t for the good Capitalists there’d be no food, nor money, nor nothing. Besides, this destructor gives employment to hundreds of men who would otherwise have none.” So saying the honest fellow picked up a firkin of butter that happened to have fallen from one of the lorries, and hove it into the fire. Then, “Thank God,” said he, “I have done my duty,” and walked away, whistling very resolutely the tune of “Blue Bananas.” Soon afterwards men came with eighty big hosepipes and quenched the embers of the fire with a deluge of milk.

Cuanduine then went his way. A little farther he came to a glade, where he found a profiteer tied to a stake upon a pile of brushwood. The unfortunate man had rashly gone for a walk unescorted, and now his captors, a dozen or so of hungry, wolfish men, were quarrelling as to who should have the honour and pleasure of applying the torch to him. Perceiving Cuanduine’s approach, they surrounded him with supplications to adjudicate between them.

“It is a pity,” said Cuanduine, “that you do not read your scriptures more closely. Let him that has never profiteered apply the torch.”

When the men had departed Cuanduine loosed the bonds of the profiteer, who went forthwith to lodge information with the police.

Cuanduine now began to retrace his steps homeward, but soon lost his way among unfamiliar roads. Presently, however, he accosted a labouring man whom he met, a flat-faced fellow with humped shoulders and vacant eyes, and asked him how many miles it might be to London.

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“Nay,” said Cuanduine, “that cannot be, for I left it no more than three hours ago. Do you mean perches?”

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“Then pray tell me by which of these roads in front I should proceed.”

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“You are fooling me, sir,” said Cuanduine. “There are but three roads yonder. If you know which of them is mine, please you to say so: if not, why, say so too, and we’ll end the matter. Now, which is it?”

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“Have you no other word in your language but ninety-nine?” asked Cuanduine.

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“That is not a large stock,” said Cuanduine. “Pray, name me some.”

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“I marvel you are so bold to keep on answering me so,” said Cuanduine. “Are there none that hold you dear?”

“Ninety-nine,” said the man.

“A wife, doubtless?”

“Ninety-nine.”

“And children?”

“Ninety-nine.”

“One to each wife? It is a moderate allowance, like your vocabulary.”

Here Mr. Robinson came up the road, looking rather hot and dusty. “How on earth did you give me the slip?” said he. “I’ve had the devil’s own job to find you.”

“See this excellent fellow here,” said Cuanduine, presenting the workman. “I wish you would hold converse with him. He seems to have but one word, Ninety-nine, and I would like to know what he means by it.”

“That is easily explained,” said Mr. Robinson. “He is probably a worker in one of Goshawk’s factories, and has been making Part Ninety-nine all his life.”

“Part Ninety-nine of what?” asked Cuanduine.

“Oh, goodness only knows: I’m sure he doesn’t know himself. It might be anything from a sparking plug to a screw for a watch. Whatever it is, he’s been making it ever since he was a kid. He can make it to perfection, but he can make nothing else. By this time he probably can think of nothing else. That’s Goshawk’s policy: one man one job, and get it Right. He’s hardly got it going properly in this country yet; but, by Jove, you should see how it works in America. They’ve whole towns out there that can only say one word, like our friend here. Think of that! A whole town in which every blessed man, woman, and child is making, or being trained to make, Part Umpty-um of some blamed thing they’ve never seen entire, or even heard the name of. There’s progress for you. That’s what has America where she is.”

“Where is she?” asked Cuanduine.

“On our necks, my boy, and don’t you forget it. I suppose our boss seems pretty big to you — coming from a backward place like Ireland, I mean. Well, Cumbersome’s big enough, as big men go in Europe. But I tell you this. He only owns what he does own by Goshawk’s permission.”

“Ninety-nine,” said the workman.

“Quite right, old chap,” said Mr. Robinson. “We mustn’t talk treason, eh? Come, Mr. Coon-dinner, let’s be getting home. There’s an aerodrome just round the corner.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”