King Goshawk (29)

By:

July 16, 2014

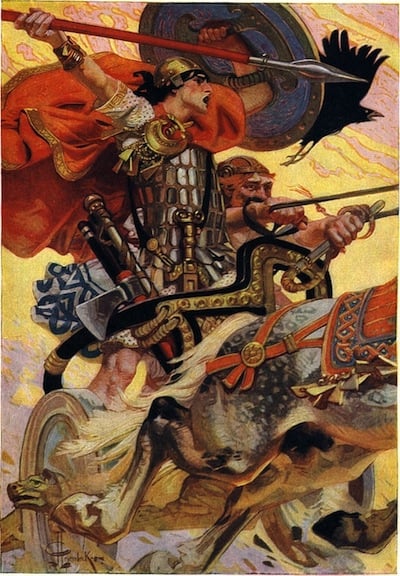

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 3: Cuanduine comes to London

This is the way London was when Cuanduine came to look upon it. All that portion of the city that lay south of the Thames was in ruins, as was also a broad belt stretching from Buckingham Palace to Shoreditch, with large isolated areas at Paddington, Hendon, and Hackney. Besides, there was scarcely any region that had not some scar to show. In the middle of Chelsea there was a crater a third of a mile in diameter and over two hundred feet deep; there was another in Maida Vale, not quite so wide, but deeper; and there were two smaller ones between Euston and Regent’s Park. Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park were a blasted wilderness; the great block of buildings between Leadenhall Street and Fenchurch Street was a mass of pounded wreckage; and most of the bridges crossing the Thames were shattered, with wooden structures spanning the gaps. On a broken arch of London Bridge dozens of young artists from New Zealand were always to be seen, sketching the ruins of St. Paul’s.

The population, of course, had greatly declined. For motives of economy no census had been taken for nearly twenty years; but it was estimated that about three million people still clung to their desolated city, fully half of whom were living, like the Dublin people, in patched-up ruins or temporary huts.

Yet in the midst of this desolation the spirit that made old England great was still alive. In the National Arsenal, which had once been the British Museum, mighty guns capable of throwing a twenty-four-inch shell two hundred miles were being turned out at a rate of a dozen a week; and in the secret laboratories of the London University grey-headed men of science were ransacking the labyrinths of chemistry for weapons that would render them obsolete.

Now, as every Irishman knows, the people of England are in every way inferior to the people of Ireland, being materialists, whereas we are idealists. This they show most particularly in their politics; for their principles are in nature so mundane and trivial, and held with such lukewarm conviction, that men of opposite parties do not regard each other as traitors, cowards, or tyrants, but even salute each other in the street, and, with characteristic hypocrisy, maintain as friendly relations as if there were nothing to divide them: all which they justify with a mean and time-serving proverb to the effect that “opinions differ.” The most momentous national problems are by these people invariably decided by vote, and since the seventeenth century all their controversies have been settled without violence. Ever unready to sacrifice anything on the altar of principle, they would no more think of burning an opponent’s house than they would of shooting him in the street. An Englishman will not even defame the character of a man he disagrees with; nor does he hold any ideal high enough to impel him to rob a bank. By this timidity and love of compromise the English are deprived of that ennobling inspiration which we draw from our martyrs, and they lose also what we have aptly named the suffrage of the dead. The reincarnation of thousands of deceased patriots to outvote the living would be impossible in an English election. The English, in fact, have scant reverence for the dead, which they express in another base and cowardly proverb: “A live ass is better than a dead lion” — a final proof of their inferiority to ourselves, who believe that there is nothing so wise and noble as a dead ass.

You may count it then, my friends, as a vice in these English that they welcomed Cuanduine most cordially to their shores. They did not believe in his celestial origin, nor did they pretend to; neither did they argue about it, but politely disregarded it, as if it mattered nothing one way or the other; an attitude which, if it did not please Cuanduine very much, left him without grounds of complaint. This policy was initiated by the Cumbersome Press, which, while joyfully heralding him as a “distinguished and brilliant intellect,” a “master mind,” a “thinker of unusual depth and seriousness, whose lessons Englishmen could not afford to ignore,” was most discreetly allusive as to his origin, maintaining always a tone which was neither incautiously credulous nor discourteously sceptical.

On the day when his arrival was expected there was gathered at Hendon by the aerodrome a bevy of bright reporters and enterprising photographers, and not a few also of the general public. The instant the hero’s foot touched the soil of England a hundred and eighty camera shutters snapped together like a clap of thunder (only not so loud nor so deep nor so rumbling, if truth be admissible in descriptive writing) ; and as he strode forth from the drome, escorted by an equerry in the livery of Lord Cumbersome, they kept on snapping like a battery of machine-guns in action. Cuanduine and the equerry then motored to an hotel, where a suite of rooms had been reserved for the hero at the Lord Cumbersome’s order. Here also were reporters and photographers, enough to overawe even the heart of him that had faced undaunted the howling mobs of Baile Atha Cliath. For these reporters had their way of him and interviewed him, harrying him with questions as hereunder set forth, namely:

What would win the Derby?

Was the modern girl maligned?

Had the short skirt come to stay?

Did men prefer clever girls or stupid?

Who would win the Little Perkington Election?

How long would the side-creased trouser remain in vogue?

Had he learnt how to play Jim-jam?

Did he believe in love at first sight?

Did he believe it possible to love more than once?

How long did love last?

Did business girls make good wives?

Should engaged couples hold hands in public?

Should the Parks be purified?

Should a girl marry for money?

What was the best way to get rich quickly?

What should be done about profiteering?

What should be done about unemployment?

Did he think the song “Blue Bananas” likely to be immortal?

Were there really men in Mars?

Should girls wear pyjamas?

What sort of undies did the ladies wear in Tír na nÓg?

— to all of which Cuanduine made such responses as his bewilderment allowed, which need not be recorded here, as they were duly misreported in the papers of the time.

The hero’s photograph also appeared in all these sheets, so that he was soon a familiar figure in the eyes of the English people. They saw him

Setting his first foot on British soil,

Setting his second foot on British soil,

Steadying his hat in the first puff of the British wind,

Smiling,

Chatting with his equerry,

Chatting with reporters,

Blinking in the sunshine,

Putting up his umbrella,

Walking in Piccadilly,

Walking in another part of Piccadilly,

Walking in the Strand,

Walking in Fleet Street,

Walking,

Sitting down,

Standing up,

Sitting down again,

Sitting on a chair,

Sitting on a seat,

With arms folded, smiling,

With arms folded, grave,

With arms at his side, grave,

With arms at his side, smiling,

With a friend,

With two friends,

With a dog,

Without a dog,

— in short, in a thousand and one poses, conditions, accompaniments, occupations, and predicaments. Never had anybody been so photographed in England, unless it might be some royal personages or the leading beauties of the cinema.

To escape this constant persecution, Cuanduine left his hotel and took him a house at Richmond.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”