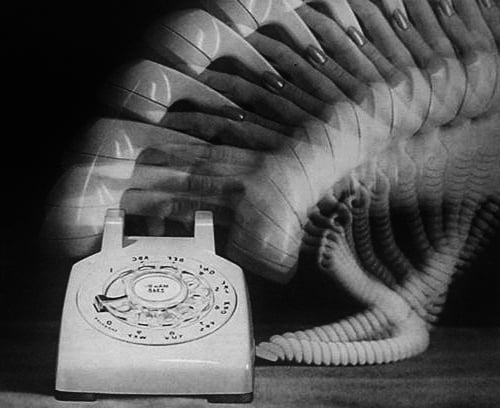

Phone Horror (7)

By:

June 23, 2014

[Seventh in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 were adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 appear here for the first time.]

“A Most Unusual Pasture”:

Toward a Lineage of Phone Horror in Twentieth-Century English Fiction

Over in England, the telephone men have their troubles, too. … Two ladies once ordered the removing of wires passing over their garden, alleging that their nephew, who thought he was entitled to their money, sent ghost messages by the wires, and the messages pervaded the house.

— Telephony magazine, September 1904

As against, say, the Americans or the Asians, the English in their fictional narratives seem never to have been too deeply disturbed by the telephone’s supernatural resonances. But the following examples have been found, either by accident or by search, and surely there are others as yet undiscovered; if you can, please add to the list by communicating with me or with the editorship. Let this be, in chronological order, the mere beginning of the UK entry in a cross-cultural concordance of phone horror.

1. “The Case of Vincent Pyrwhit,” Barry Pain

Publication: Stories in the Dark (1911)

Premise: A murder is prophesied by telephone.

Key quote:

I noticed an Erichsen’s extension standing on his writing table. I said: “I didn’t know that telephones had penetrated into the villages yet.”

“Yes,” he said, “I believe they are common enough now …”

Notes: Terse; dry; quite short. Less scary than ironic, and not terribly much of that. Interesting for small historical details — “Erichsen’s extension,” whomsoever that might refer to; the phone has a “green cord” and a “prolonged, rattling ring.” More than anything, perhaps, the story was conceived as a novelty item — let’s see if this jangly whatsit plays as a spook machine — but relatively little consideration is given to fleshing out the conceit.

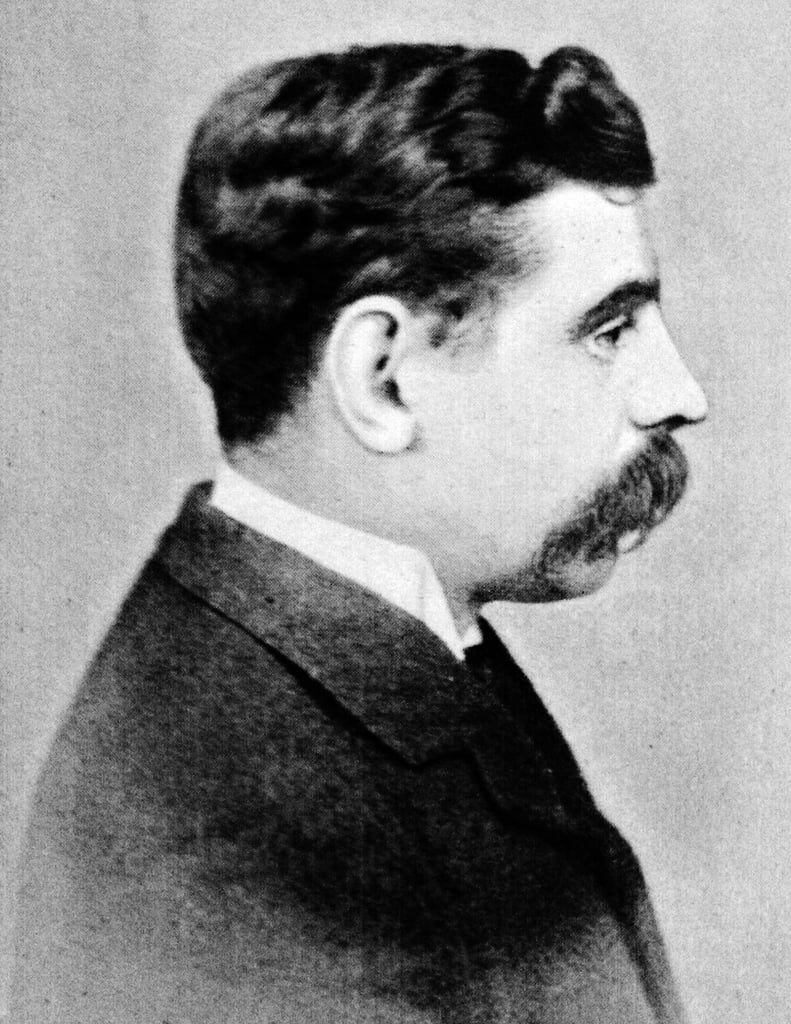

2. “The Confession of Charles Linkworth,” E. F. Benson

Publication: The Room in the Tower and Other Stories (1912)

Premise: Dr. Teesdale has attended, as medical official, the execution by hanging of condemned killer Charles Linkworth; he is troubled by the criminal’s stout refusal to confess, even to the moment of his death. The doctor is “a considerable student of the occult,” and “a believer in the doctrine of future life”; and so upon receiving a series of strange, unattributed phone calls from the prison where Linkworth was held, consisting of inchoate mutterings and strangled whispers, he is perfectly prepared to conclude that it is the hanged man’s ghost attempting contact. Further, he sets out to obtain, through these communications, the all-important confession, the only means by which Linkworth’s soul will be saved — or, as the English say, his ghost laid.

Key quote:

… ever and again his mind kept coming back to that strange little incident of the telephone. Often and often he had been rung up by some mistake, often and often he had been put on to the wrong number by the Exchange, but there was something in this very subdued ringing of the telephone bell, and the unintelligible whisperings at the other end, that suggested a very curious train of reflection to his mind, and soon he found himself pacing up and down his room, with his thoughts eagerly feeding on a most unusual pasture.

Notes: This instance of what Benson called his “spook stories” — he wrote many — is strong, its creeps substantial. The prose is for the most part delicately dealt, while the sensibility exemplifies the fleeting confluence of scientific adventure and objective occultism that was tracked in our previous “Phone Horror” installment. The lingering effect, however, is diminished notably by the concluding appearance of the ghost itself — a performance, interestingly, put on for the sole purpose of convincing, or “converting,” the spirit-debunking prison chaplain.

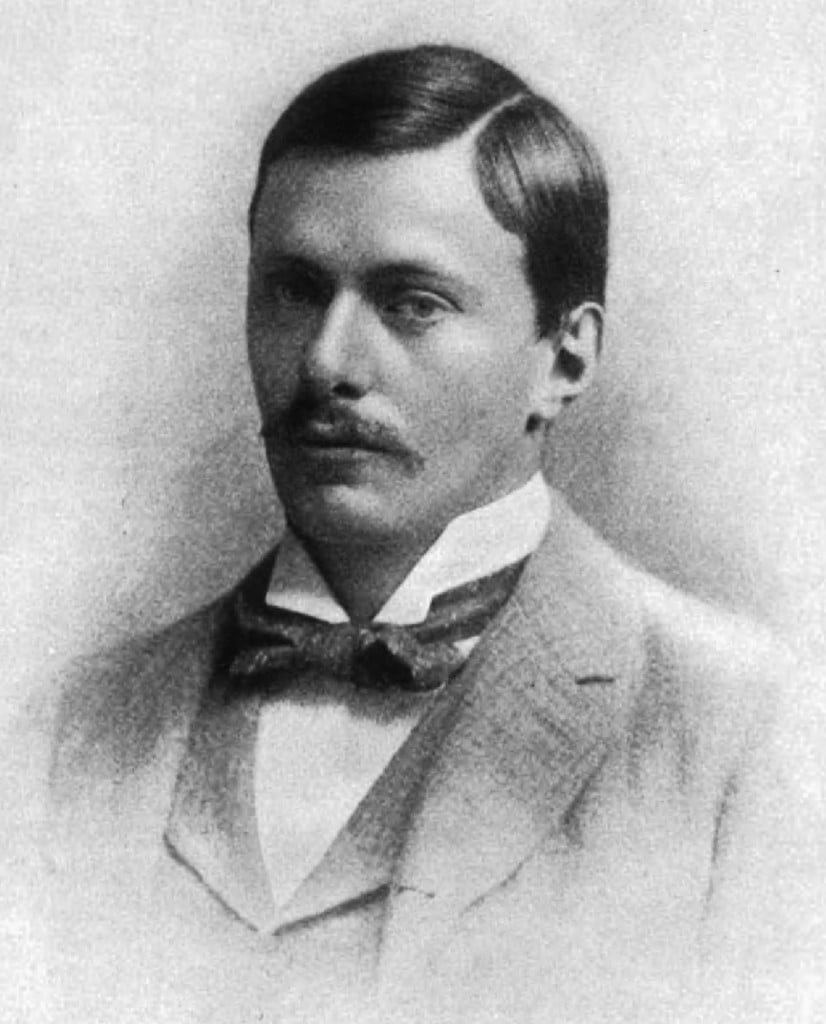

3. “You May Telephone from Here,” Algernon Blackwood

Publication: Ten Minute Stories (1914)

Premise: Two women stay up late in a townhouse on a foggy North Kensington night. One, identified only as “the wife,” lives with her husband, who is away on a sea voyage; the other is her visiting cousin. The newly installed phone rings (actually, it “tinkled faintly, but gave no proper ring”), yet there’s no one there; the operator, queried, apologizes that lines are crossed in the area. But as the wee hours deepen, the wife feels “almost as if there was someone else in the flat—someone besides ourselves and the servants, I mean.” The phone rings again — and this time the wife hears her husband’s voice, muffled and broken up as if at a great distance, coming from beyond wind and waves. But it can’t be him — ?

Key quote:

… it began again: first with little soft tentative noises, very faint, troubled, hurried, buried almost out of hearing inside the box; then louder and louder, with sharp jerks — finally with a challenging and alarming peal.

Notes: Though far from first-rate Blackwood, and antiquated even as antiques go, this isn’t a bad little creeper — and quite unusual in phone horror for ending in a revelation of life, not death.

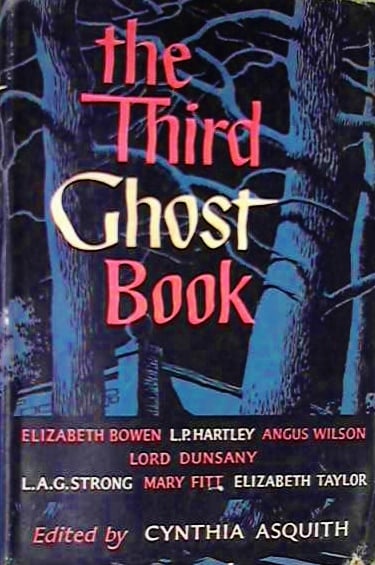

4. “The Telephone,” Mary Treadgold

Publication: The Third Ghost Book, ed. Lady Cynthia Asquith (1955)

Premise: The young female narrator falls in love with Allan, who is married. His wife, Katherine, discovers the affair, and they reach some melancholy private arrangement. The new lovers seclude themselves in the Scottish Highlands, and soon learn that Katherine has died of heart failure; a burden of sorrow, we’re given to assume. Then Allan begins to receive telephone calls. They appear to originate from the London flat he shared with his dead wife — and Allan says it is Katherine on the line.

Key quote:

… in the daytime I avoided looking at the dead black telephone inert on its old-fashioned stand in the hall. At night I lay awake, trying not to picture that telephone wire running tautly underground away from our cottage, running steadily south, straight down through the border hills, down through England …

Notes: …down into the solitudes of our guilt, the next paragraph ends — nicely completing the image of subterranean fates underpinning the sad, treacherous, inexorable matters of the day, such as falling in love with the wrong person, dying from sorrow, and crumbling beneath guilt. Guilt is so often the emotional driver of phone fear, the victim’s real vulnerability; see “Night Call” and When Michael Calls. The science fiction critic Thomas M. Disch commended “The Telephone” thusly: “The brush of a sleeve, a stifled sigh — these are to be the stuff of horror, and in the hands of a good writer they serve very well.” Not surprisingly for Mary Treadgold, best known for her children’s books, the ending is hopeful, though no less haunted.

5. Memento Mori, Muriel Spark

Publication: 1959

Premise: An inbred, enfeebled group of Londoners in their seventies and eighties practice, literally to their dying days, the petty jealousies they’ve crafted over fifty years of toxic interrelation. The outer, or other, world intrudes in the form of anonymous telephone calls always bearing the same message: “Remember that you must die.” (The novel’s title, translated.) At first the calls are focused on one member of the group; they then spread virally to another and another and another, until finally all are implicated in the unanswerable decree, and cruel fate has its way.

Key quote:

“If I had my life over again I should form the habit of nightly composing myself to thoughts of death. I would practice, as it were, the remembrance of death. There is no other practice which so intensifies life … Without an ever-present sense of death life is insipid. You might as well live on the whites of eggs.”

Notes: Spark’s second novel (adapted by the BBC in 1992, directed by Jack Clayton and starring Maggie Smith, above) is characteristically wry, cool, and observant, and so nonjudgmental that it could easily be read as pitiless. While no hot pot of scares — the novels that surround it, The Comforters (1955) and The Ballad of Peckham Rye (1960), are far more unnerving — it indubitably belongs in, if not to, the phone horror genre, chiefly because no rational, let alone singular, explanation is offered to account for the harassing communications, in which the voice of the caller changes depending on the recipient. Thus, to different people the death-declaring voice sounds “like that of a common man … The tone was strictly factual … He sounded young, like a Teddy-boy … It was the voice of a cultured, middle-aged man … the tone is sinister in the extreme … It was the voice of a very civil young man … a man well advanced in years with a cracked and rather shaky voice and a suppliant tone.” The retired police inspector charged by the others with investigating the calls, himself a man of wintry years, muses touchingly how strange it is “that mine is always a woman. Everyone else gets a man on the line to them, but mine is always this woman, gentle-spoken and respectful.”

6. Beard’s Roman Women, Anthony Burgess

Publication: 1976

Premise: Robert Beard, an English television writer, is in Rome to work on a script about Byron, the Shelleys, and the writing of Frankenstein (to be done as a musical). When not working, wandering, getting drunk, recalling fond amours or bouts of sexual savagery, Beard has phone conversations with Leonora, the late wife who now claims to be quite alive, lying scornful and horny in the same hospital where Beard saw her die from alcoholic cirrhosis.

Key quote:

“Yes?” Beard said to the telephone.

“Darling, I’m dying. They’ve put me in this small room at the end of the ward. Come and shag me. I want to be shagged before I die.”

“But they’re showing my film on television. You know, the one about Frankenstein.” …

“Fucking dirty swine. Bigamous bastard. I’ll haunt you, you’ll see. I’ll be hovering over your filthy bed, laughing at your fucking ineptitude.”

Notes: Burgess seems to have written this in the full ferocious pitch of a raging bender. Vivid and funny, it is also more than a little frightening — as intersexual invective, not ghostly invention. Like Memento Mori, it tags some of the key themes noted in our previous examples of phone horror (a deceased loved one’s call from beyond; survivor’s guilt as Achilles’ heel); but the mood is the hyperreality of seared nerves and self-disgust, the effect to render the spectral dimension just as emotionally corrosive and spiritually rotten as the physical. Luckily the characters are evenly matched in bathos and bitchery, the prose alive with carnality, and the novel bracingly brief.

We have a lot of popular, and irreconcilable, notions about the English. They are brilliant; they are dotty. They articulate well; they “harrumph” a lot. They are austere; they are stylish. They are efficient; they are twits. They are resolutely polite; they are intrinsically snobbish. They are humorless; they are hilarious. They have sexy accents; they have gross teeth. In fact they are as genuinely ungeneralizable as any other people, or “peoples,” and nothing in English fiction’s employment of phone horror will tell us how best to stereotype them. Some uses are mordantly humorous, but none is solely comic; while none is calculated for the effect of deep terror, most have a greater or lesser chill factor. Sometimes phone horror is a spiritual element, other times merely the deus ex machina by which characters are compelled to deal with mortal matters they’d rather deflect.

Stretching it out to its broadest perspective (with every cognizance that to do so is folly, given this merely tentative sampling), it seems that the Brits have, over the course of the last hundred-odd years — unlike the aforegrouped Americans and Asians — left well behind the superstitions requisite to phone horror. For them, a phone call from the dead, if it occurs at all, is adjunct to normal life — job, marriage, betrayal, compromise, adjustment, and finally decay — and so not a shock at all, but merely an unexpected, esoteric, sometimes titillating or irritating spice in the lifelong repast whose closing course is the palate-cleansing of death.

Fair enough: that’s the one meal we all share, no matter our culture or country.

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |