Phone Horror (6)

By:

June 19, 2014

[Sixth in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 were adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 appear here for the first time.]

Phone Horror: A Brief History of a Crypto-Science

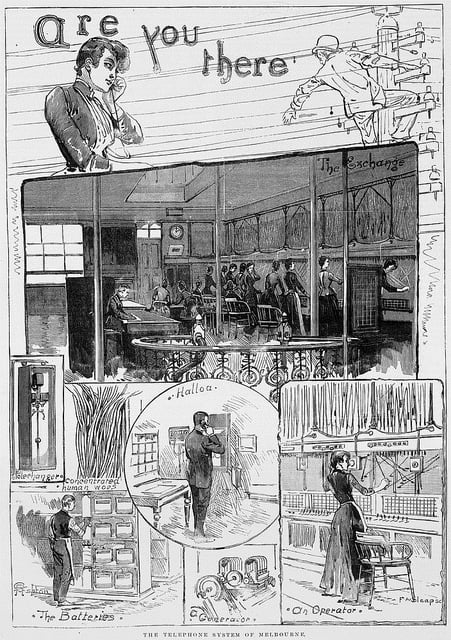

Alexander Graham Bell, whether he invented it or not (he didn’t — not alone), was the first to patent a telephonic device; that was in 1876. The first long-distance line was strung the next year, and it was another year before the first commercial telephone exchange was established (in New Haven, Connecticut). Many European countries marketed telephones for home and office immediately, but it wasn’t until the mid-1890s, after Bell’s initial patents had lapsed, that the number of phones in normal use — a metric known as “teledensity” — began to increase significantly in the US. By the first years of the new century, the device was widespread; even those who couldn’t afford their own could access one at the local courthouse or general store.

Almost from the instant of its infiltration into everyday life, the phone was seen as having otherworldly potential — and utility as sucker-bait for the faithful. In 1881, a weekly publication was founded in Brisbane, Australia, for the growing community of religious believers seeking contact with “the other side”; it was called The Telephone. In 1895, the quarterly review Borderland printed a series proposing and extolling “the prayer telephone,” a kooky theory of a “celestial Telephone Exchange.”

But the same year, Borderland also carried an item titled “Did the Ghost Use the Telephone?” Submitted as fact by an “esteemed correspondent,” this was the story of a man who received a call about his ailing sister, who was being treated at their parents’ home in a distant town. “Go to your father’s house at once,” a voice said. “Poor Nelly is dead.” The man hurried there; his sister was indeed dead. But no one admitted to having called him, and other circumstances made it seem impossible for a phone communication to have gone through that day at all. Fanciful or not, this was surely one of the first recorded instances of what D. Scott Rogo and Raymond Bayless would, some 80 years later, be driven to study and taxonomize in Phone Calls from the Dead (1979).

In those dawning years, the phone was regularly instanced as a modern miracle, for putting within practical reach what had only a few years before been deemed impossible. The chief impossibility — which the phonograph and radio also played their role in defeating — was that of being able to hear what you could not see. “All previous generations, as the result of invariable experience,” wrote Fremont Rider in Are the Dead Alive? (1909), “linked together as an obvious axiom that when the ear could hear the eye must be able to see the speaker. That assumption has been broken down by the telephone.” Not only was the telephone in itself a miracle; it seemed to herald an age of miracles, of expanded consciousness and interconnectedness to earthly, and unearthly, experience. “I no longer fear being written down as a lunatic,” Rider proclaimed, “when I say that I have the same confidence as to the certainty of communication with friends who have passed over into the other world as I have in our ability to talk through the telephone to distant friends.”

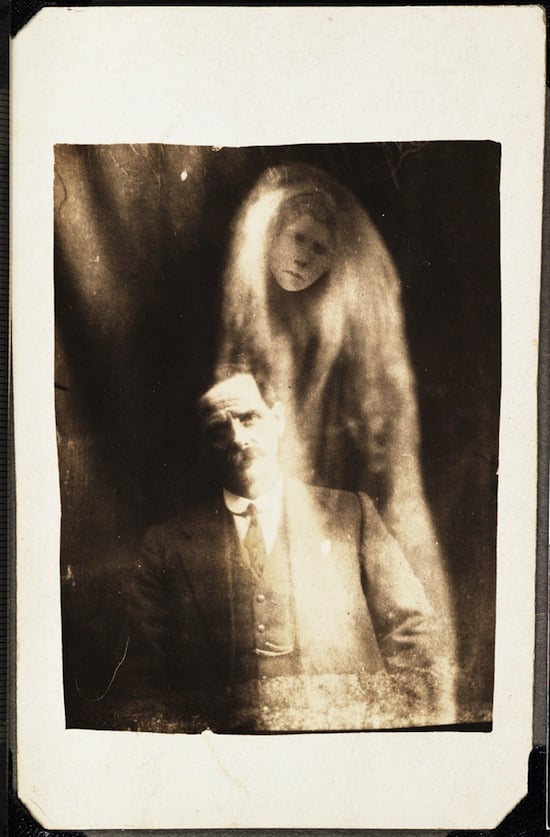

The impossibilities rendered possible by the telephone upped the ante considerably on Spiritualism, heretofore mostly a domesticated, lace-doily affair whose grip on the public fascination was typified by the Fox sisters of Rochester, New York, world-famous in the 1840s and ’50s for their table-tapping séances. (Karl Marx had the Foxes, and Spiritualism generally, in mind when he wrote of his symbolic commodity, the table, that, “in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than ‘table-turning’ ever was.”) Technology brought a redoubled masculine presence to the Spiritualist fold — bearded rationalists who sought to remove matters of magic and spirit from the parlor to the laboratory. Many of these represented the psychical-research societies that were founded in the UK and the US in 1882 and 1884, respectively; some were esteemed authors and intellectuals like Arthur Conan Doyle and William James. In the intellectual-academic terms of the fin de siècle, it was hipper than hip to log psychic experiments, monitor ghostly static through ear trumpets, study spirit photographs, and string live wires between this world and the next.

Many of these were dogmatic, joyless enterprises meant to lobotomize the fantastic with the icepick of science. But for other researchers, techno-spiritualism was the pursuit of new intellectual excitement. The postulate was not only thrilling but also supremely logical: if technology could so transform our conception of the material world and its limits, why not our relationship to realms beyond? Included in Frederic W. H. Myers’s two-volume Human Personality and its Survival of Bodily Death (1903) is the transcription of a mediumistic exchange between a man, Jim, and his dead friend, George:

[What do you do, George, where you are?]

I am scarcely able to do anything yet; I am just awakened to the reality of life after death. … I can hear you speak. Your voice, Jim, I can distinguish with your accent and articulation, but it sounds like a big bass drum. Mine would sound to you like the faintest whisper.

[Our conversation then is something like telephoning?]

Yes.

[By long distance telephone.]

George, we’re told, laughs — no doubt at the aptness of Jim’s metaphor.

That same year, sociologists Henri Hubert and Marcel Mauss suggested that “magic” — by which they meant a whole congeries of transformative and alchemical practices — was the natural ally of, on the one hand, religion, and on the other, technology and science: “While religion tends toward metaphysics and becomes incorporated in the creation of images of the ideal, magic leaves through numerous slits the mystical life from whence it draws its energy, becomes part of mundane life, and provides services for it.” (The first conception of the “service provider”? The mysticism of one millennium becomes the hardware of the next.)

By the beginning of the twentieth century, both credentialed men of science and mandarins of scientific suasion were using the telephone as rationalist metaphor for the paranormal phenomena in which they fervently believed and in whose cause they were busily accruing empirical data. In 1909’s Cases of Spiritistic Identification, Roberto Bozzano equated spirit and telephone communication, vide the “mixture of dialogues” evidenced in the automatic writings of Helen Verrall, a then-prominent medium: “Does it not seem [when reading these writings] that one is listening to the fragments of conversation sometimes gathered unvoluntarily [sic] when using a telephone? … Does it not follow that in both cases one must find at each end of the wire, or station of wireless, a real and intelligent communicator?”

The early history of the conflation of telephones and ghosts can be seen as part of a broader intellectual sweep — away from Victorian and Gilded Age conformity on the one hand and the heavy-lidded self-infatuation of romanticism on the other, toward a robust, adventurous, yet solidly evidence- and performance-based sensibility. The latter was in many ways aligned with the better humanistic ideals of the Progressive era, but it also shared much with Rooseveltian (not to mention Edwardian) principles of masculine conquest and the prerogatives of empire. There is something in us, surely more intrinsically male than female, and more Western than Eastern, that wishes to not simply experience but to resolve and put away a mystery, to move always on the assumption that we can and should know, and thus conquer, the unknown — often for no better reason but that the unknown mustn’t be allowed to remain unknown, as a mountain mustn’t be left unclimbed or a commodity left uncommercialized. To a certain kind of man, for any material or immaterial phenomenon to simply be left alone is a mark of failure — a symbol of surrender, and of one’s own smallness.

That heedless drive, that vigor in wrestling down the ineffable and wiring spirit to an electronic receiver, propelled the millennial ghost-phone science whose sole surviving traces, following a century’s worth of abomination and innovation and the resultant wanderings of the collective dream life, are found in the cheap shocks, formal tropes, and occasional profundities of phone horror. But in that long-gone time, how dizzying, how fantastic must have seemed the possibilities that lay before the human race! The key to the telephone as miracle, metaphor, and medium for ghosts lay in what Hubert and Mauss called the “numerous slits” in reality and rationalism that allow the mundane to commingle with the mystical, and mortal matter to be infused with a spirit which lures our fancy with the prospect of something eternal.

“Many steps in the last few years have been taken upward toward the boundary line that separates the spirit from matter,” Isaac K. Funk wrote in 1911. “The phonograph that photographs the voice, the long-distance telephone which enables us to hear the voice of a friend tho the ocean intervenes, the wireless telegraph which by waves of ether is a prophecy of conversation with the inhabitants on other planets, the x-ray giving us power to look through solids, the kinetoscope that helps us to see events of the past in action — where is the end?”

A few years after that was written, World War I began, rendering insignificant many matters that had recently appeared monumental. But for a while there, magic and technology seemed not separate but interdependent adventures, each enabling the potential of the other, twin beacons illuminating a new century and a world without end.

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |