Phone Horror (3)

By:

June 13, 2014

[Third in a series of 10 posts on representations of the telephone as instrument of fear, conduit of spirits, and messenger of madness. Parts 1-4 are adapted from posts published at the blog The Face at the Window in 2005-06; parts 5-10 will appear here for the first time.]

When Michael Calls

Somewhere in New England, there was a house. In the house lived a woman named Helen: thirties, divorced, antiques dealer. The house normally bustled with the comings and goings of her friends, her relatives, and even her ex-husband. But this night, a night not long before Halloween, it was empty but for Helen.

The lights were out downstairs. The telephone rang.

She frowned at the school things piled on the stairs and picked up the receiver of the telephone, which was sitting on a meticulously refinished Sheraton table at the entrance to the living room.

“Auntie Helen?”

She was looking through the glass to the right of the door, looking beyond the porch at the yard, where Randle had left his shovel leaning against the sign that read “HELEN CONNELLY—ANTIQUES,” and at first she wasn’t certain just what she’d heard.

“Yes … hello? Is that you, Rosalind?”

“Auntie Helen …” She frowned; not a girl’s voice. “Auntie Helen, I missed the school bus. Will you come get me?”

Wrong number, she thought. “Who is this?”

“It’s Michael, Auntie Helen.”

“What?”

“It’s Michael.”

Helen said nothing at all.

“Are you coming?”

“Just … a minute. Now, who is this?” But the connection was broken before she finished.

Michael, it transpires, is Helen’s nephew, the son of her deceased sister. Or rather, he was: Michael has been dead for 16 years. And now he’s on the phone. Calling Helen “Auntie,” just as he used to. The voice is … the same? Helen’s not certain. But she’s scared.

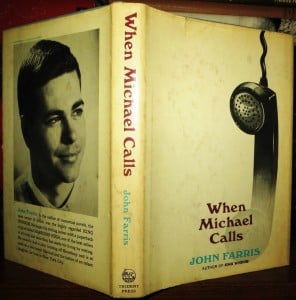

When Michael Calls originated in the fertile cerebrum of cult novelist John Farris. Published in 1967, it is a lean chiller-thriller, all narrative, little art in the prose—save for the unique and underrated art of telling a no-nonsense story about intelligent adults who are suddenly caught in otherworldly circumstances. The novel was made into a TV-movie, directed by Philip Leacock (British-born veteran of episodic US television, and brother of visionary documentarian Richard Leacock), scripted by James Bridges (soon to be director of such trendy Hollywood fare as The Paper Chase, The China Syndrome, and Urban Cowboy), and starring Elizabeth Ashley, Ben Gazzara, and Michael Douglas. It aired as an “ABC Movie of the Week” on February 5, 1972, and it was in this form that I first made the acquaintance of Michael’s haunting voice, and first learned to be afraid of the phone.

I’d have been all of five and a half when the movie first aired, but I must have encountered a rerun not long after. Its memory is inextricable with the house I lived in as a child, the bed I dreamed in, the teeming darkness of the room that was mine. The larger context of childhood is a panoramic blur, but those impressions—house, dream, teem—are engraved and ineradicable. Likewise, the tone of Michael’s telephonic voice runs in my mind as unvaryingly as an archival recording, while the film as a whole devolves to a generality.

Therefore, speaking generally: In its early stages, When Michael Calls (once marketed in VHS under the inane alternate title Shattered Silence; or maybe it’s Silence Shattered—the graphics confound) offers the same pleasures as the novel—dialogue you can actually imagine being spoken, plausible interactions between mindful grownups, an ongoing attempt, combining the frightened and the commonsensical, to devise sound explanations for inexplicable events. Additionally, there is the kind of windswept New England atmosphere that could pimple the flesh of the most rational goose. The cast may be overqualified for such a modest project, but Ashley, Gazzara, and Douglas are all first-rate, never smirking at the story that engages them, never falling back on smug memories of superior work to carry them through these pulpy doings.

An adult reviewing of Michael is both revelation renewed (what used to be scary still is) and desire defeated (it’s just not that strong on the whole). There is a compulsion in the film, finally, to convert a refreshingly naturalistic portrayal into cardboard (not an uncommon complaint against a TV-movie), and its peak is premature: richly unnerving for its first part, it’s progressively, enervatingly less so in its second. But to the extent the movie has left its identifiable prints on my stunted psyche, When Michael Calls is more important for the things it does just right than those it does less than right.

A word about the intriguing John Farris. He began as something of a prodigy, writing the 1959 bestseller Harrison High—a sort of adolescent Peyton Place—when just out of high school himself. It was followed by several sequels. Before and after Michael, Farris produced numerous thrillers and straight dramatic novels under both his own name and the pseudonym Steve Brackeen. In the ‘70s he wrote and directed a cult slasher movie, Dear Dead Delilah, starring Agnes Moorehead and Will Geer, and published The Fury, basis for the 1978 Brian DePalma movie (for which Farris wrote the screenplay). There have been several other novels since, but All Heads Turn When the Hunt Goes By (1977) is evidently held in special esteem by aficionados. The author himself seems quite privacy-minded, even curmudgeonly when met with attempts to draw him out; but a few of his more devoted fans maintain a website devoted to his work, with interviews, photos, and well-written essays on the Farris oeuvre.

But back to Michael. That is, back to the telephone, and the lost spirit at the other end of it. I’ve admitted the power of a ringing phone to set my heart racing with a shock out of any rational proportion to the event. Undeniably, the fear is greater when I’m alone; when I’m not expecting a call; when the wind blows branches against the window and the sky outside is edging dark blue into black. Among others in this dream world I’ve constructed, I have Michael to thank for that. I note the quality of his voice. It’s androgynous, or rather unisex: the voice of a male teenager, certainly, but with a woman’s emotional urgency pushing it up the throat. The tone is both inhuman and too human, the inconsolable sob only barely contained—and then not contained at all. The voice is not merely frightened; it’s fearful to the point of madness.

Do dead people feel fright? Do they cower, feel cold, lost, alone? Can a ghost fear itself?

Michael’s voice is that of the ghost, the demon, who has realized, just this instant, what he is. Such pathos and terror in that voice: maybe that’s why it haunts me. Maybe that’s why, even now, when the phone rings in the dark, far past the hour when considerate folk have ceased calling each other, I freeze when picking up the receiver. Why I half expect to hear Michael begging me to come for him.

I’ll not reveal or even imply what the solution to the Michael situation might be. Suffice to say both that it is worth tracking, and that the creepiest passage in the novel is also the creepiest scene in the movie. It’s the one I’ve never forgotten the sound or feel of. As it occurs early in the narrative and gives nothing away, I’ll quote the Farris original in full.

About eleven the phone rang again, startling her. She had been absorbed in an expensive, beautifully photographed study of antebellum Louisiana mansions which a friend had loaned to her, and the wind had lulled her into a series of yawns. Helen sat up straight, and a dark bust of a child caught her eye.

“Time for all good little boys to be asleep,” she said, looking again at the pendulum clock on the wall opposite her desk to check the time. And she felt a little worried, not because it might be the same boy calling again, but because she was automatically assuming, whenever the telephone rang, that it was him.

After all, he’d had his fun.

Yes, but, she thought, and hurried across the foyer to lift the receiver before Peggy woke up.

She heard someone crying.

You’ve had your fun, Helen tried to say, but she couldn’t; her mouth had dried up.

He was weeping this time, heartbroken, and his sobs shocked her because it wasn’t a child playacting; she was certain of that. He was terrified, helpless, alone.

“Auntie Helen—”

“Y-yes—”

“I’m … home … and there’s … nobody … here.”

“Oh, my God,” Helen said quickly and harshly, “don’t keep this up. Whoever you are, please—”

“There’s … nobody here. Where’s my mother?”

The wind outside, to which she had paid little attention for the last hour, suddenly turned on the house and thumped at the door. Helen fell back against the table, trembling.

“Where’s Craig? Where’s my brother?”

“Please,” Helen whispered. “What are you trying to do?”

He was weeping again. She put the receiver down on the table and ran from it, into the kitchen. But the blackness outside the windows was too forbidding; she couldn’t stay there. And it seemed she hadn’t escaped him after all; she was still trembling, still vulnerable, and still pathetically frightened for a mature woman who was sure that she knew a great deal about the foibles of children.

Yes, real children. But this one is a sadistic, depressing ogre.

When Helen felt she could breathe normally, she returned to the foyer and picked up the receiver of the telephone. She heard nothing this time except the sighing, the tricky fade and rise of the wind, somewhere.

I’m going to be rid of you, she thought. I’m going to stop you if it takes— “Hello,” she said, and paused. “You wanted to talk to me. That’s a good idea. I certainly want to talk to you.” Again Helen paused. “I know you’re still there, so why don’t you say something? How long do you think—”

He screamed then, not in her ear but seemingly from a distance, and Helen cringed.

“Michael!” she said, not meaning to. “Mi—”

“I’m dead, aren’t I? I’m dead, I’m dead!”

***

MORE HORROR ON HILOBROW: Early ’60s Horror, a series by David Smay | Phone Horror, a series by Devin McKinney | Philip Stone’s Hat-Trick | Shocking Blocking: Candyman | Shocking Blocking: A Bucket of Blood | Kenneth Anger | Sax Rohmer | August Derleth | Edgar Ulmer | Vincent Price | Max von Sydow | Lon Chaney Sr. | James Whale | Wes Craven | Roman Polanski | Ed Wood | John Carpenter | George A. Romero | David Cronenberg | Roger Corman | Georges Franju | Shirley Jackson | Jacques Tourneur | Ray Bradbury | Edgar Allan Poe | Algernon Blackwood | H.P. Lovecraft | Clark Ashton Smith | Gaston Leroux |