King Goshawk (9)

By:

February 24, 2014

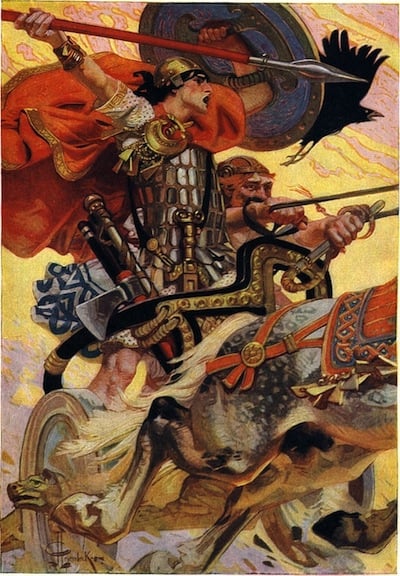

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 9: Why the Censors were so Zealous

You must understand that in those days every action, word, and thought of which man is capable was most thoroughly regulated by law. Like every other product of human endeavour, the process of legislation had been so perfected and accelerated by the marvellous progress of science during the previous quarter of a century, that the output of laws at this period baffles computation. Indeed, there were so many that it had been found necessary to double the number of judges; yet even so it would have been impossible to administer all the new statutes and punish all the new crimes without rather neglecting the old ones. (It was for this reason that Cúchulainn was able to get away with an assault or two, so long as he kept his hands off millionaires.) The penalties for breach of any law were necessarily very severe, for the complexity of the system made the smallest infringement a matter of such consequence that only the most powerful deterrents could save the courts from being glutted with cases. So great, however, was the legislative zeal of the age that although, as a contemporary wit observed, there were already so many laws that it was almost impossible to obey one without breaking another, nevertheless the promulgation of new ones continued unabated, so that it had become a matter of vital necessity for every citizen to read his newspaper in the morning with the closest attention, lest inadvertently he should commit an act which had been made criminal while he was in bed; as happened once to some forty thousand people of Dublin, who on a morning in March found themselves lodged in gaol for blowing their noses in public, being unaware that this action had just been incorporated as Schedule 678 of the Public Modesty Act.

However, there was as yet no law to protect the wise from the malice of the ignorant; though there were many to protect the ignorant from the assistance of the wise. Hence the fate that befell the Philosopher in our first chapter.

You must further understand that these were the days of paternal government. All over the world the governments had decided to abolish temptation, it being generally conceded, by philanthropists, social reformers, and statisticians, that man’s character was now so weak that at the mere appearance of temptation he must instantly succumb. The manufacture of wine, beer, spirits, and tobacco had long since been entirely suppressed. The vine and the tobacco plant were actually extinct, and in France there was a law ordaining that any one who should see a wild seedling of either must, under severe penalties, report it at once to the authorities for destruction. Substitutes for the banned commodities were, however, illicitly manufactured in great abundance. The Germans invented an imitation beer, made by soaking scrap iron in a mixture of vinegar and water; there was an insuppressible trade in Ireland in a kind of whisky of immense strength and unknown origin; and the ingenuity of the French had succeeded in extracting a very potent liquor from the common blackberry. For tobacco-substitute, every conceivable plant had been put under contribution, the chopped and dried leaves being usually smoked in pipes of plain deal, which, in the event of a raid by the Inspectors of Morals, would be readily consumed if thrust into a fire. Some of the more venturesome would even smoke cigars of brown paper in the street, and if they saw an Inspector approach, would extinguish and unroll it and wrap it like parcelling round a cake of soap or some such trifle kept for the purpose.

Even more thorough were the methods employed to save the citizens from the temptations of the flesh. The costumes of women, both as to cut and material, were all regulated by statute, the length of the skirt and the thickness of the stockings being the subjects of most stringent legislation; for the enforcement of which the Inspectors were furnished with tape-measures and calipers, with instructions to test any garment that might excite their suspicions.

Needless to say, the arts had received a full share of the attention of these paternal governments. The nude was a forbidden subject; and there had been a great holocaust of existing works in this genre many years ago. Fully two-fifths of the world’s literature had suffered the same fate, and another fifth had been so mutilated by the expurgators as to have been rendered unrecognisable to its authors. The Old Testament had been reduced to a collection of scraps, somewhat resembling the Greek Anthology; and even the New Testament had been purged of the plainer-spoken words of Christ which were offensive to modern taste. All new works had to undergo a prolonged inspection by a board of Censors, whose jurisdiction, however, did not extend to musical comedies or Sunday papers.

But the efforts of the governments to abolish the occasions of sin did not end here. It was ordained that if a person were to behave in such a way as to tempt any one to murder him, he could be arrested and imprisoned at the President’s pleasure; to abolish the temptation to bear false witness, the practice of calling witnesses in legal proceedings was being gradually discontinued; and anybody whose poverty might render him liable to steal could be put under restraint until such time as his circumstances should improve. The Party of Civil Liberty, however, had by tremendous exertions succeeded in preventing the passing of a law forbidding the rich to flaunt their wealth in the faces of the poor. It was but a trifling omission from such an exhaustive code. Such indeed was the zeal of the authorities in their war against temptation that it was a frequent occurrence for the police on duty in the law-courts to arrest all the members of the public present, the jury, the lawyers, and even the judge himself, to save them from hearing some unsavoury detail of a case.

Yet in spite of all these laws and regulations the general behaviour of the human race was in no wise improved; a thing which the purveyors of morals were hard set to explain. Wars and individual murders were more frequent than ever before; thoroughfares in the great cities were often rendered impassable on Saturdays and Sundays by the prostrate forms of men and women drunk with poteen or blackberry wine; and the white slave traffic was paying dividends of sixty-two per cent on its ordinary shares, which were openly purchased by respectable citizens. Governments and peoples still preserved an attitude of mistrust and feelings of hatred in their relations with one another; and internal politics were largely a matter of flamboyant posters, mean little handbills, and dirty language.

So much for the measures taken for the elimination of moral temptations from the ways of the world. Political and social stability were preserved by the same means; there being in every country a law forbidding the speaking or writing of any word declaring, implying, or insinuating that the legislative, executive, or judicial system of that country was not the best conceivable for that country. Thus in one country it would be forbidden to criticise plutocracy disguised as monarchy; in another to criticise plutocracy disguised as republicanism; and in Ireland it was high treason to condemn the system of flamboyant posters, mean little hand-bills, and dirty language. It was customary also for states entering into an alliance to make a mutual compact by which each state was to suppress criticism of the government of the other. Hence the Spaniards and Portuguese could criticise neither monarchy nor republicanism; and the Irish and Russians were debarred from comparing capitalism with communism; as for the English, so multifarious were their alliances and understandings that they could criticise nothing at all: which suited their temperament to perfection.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”