King Goshawk (6)

By:

February 3, 2014

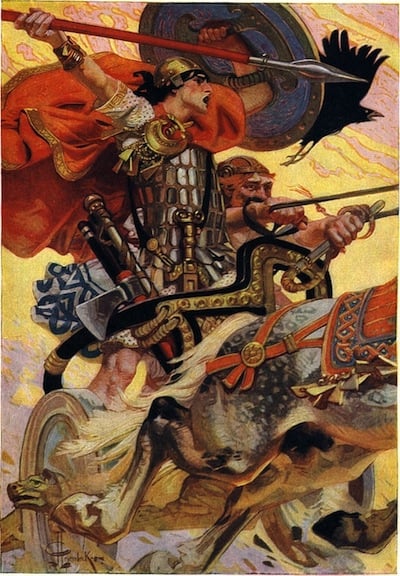

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 6: Cúchulainn takes a Walk

Thus clothed and fed, Cúchulainn set forth with the Philosopher to explore the city. What a sight was here for eyes accustomed to the splendours of Tír na nÓg. Come, O Muse, whoever you be, that stood by the elbow of immortal Zola, take this pen of mine and pump it full of such foul and fetid ink as shall describe it worthily. To what shall I compare it? A festering corpse, maggot-crawling, under a carrion-kissing sun? A loathly figure, yet insufficient: for your maggot thrives on corruption, and grows sleeker with the progression of putridity (O happy maggot, whom the dross of the world trammels not, had you but an immortal soul how surely would it aspire heavenward!). But your lord of creation rots with his environment; so the true symbol of our city is a carrion so pestilent that it corrupts its own maggots.

What ruin and decay were here: what filth and litter: what nauseating stenches. The houses were so crazy with age and so shaken with bombardments that there was scarce one that could stand without assistance: therefore they were held together by plates and rivets, or held apart by cross-beams, or braced up by scaffoldings, so that the street had the appearance of a dead forest. (Was it not a strange perversity that slew the living tree to lengthen the days of these tottering skeletons?) Many of the houses were roofless; others were inhabited only in their lower storeys; some had collapsed altogether, and squatters had built them huts of wood or mud or patchwork on the hard-pounded rubble. The streets were ankle-deep in dung and mire; craters yawned in their midst; piles of wrecked masonry obstructed them. Rivulets ran where the gutters had been. Foul sewer smells issued from holes and cracks.

Fit lairage was this for the tragomaschaloid mob that jostled the celestial visitor to the realms of earth. What stink of breath and body assailed his nostrils; what debased accents, raucous voices, and evil language offended his hearing; what grime, what running sores, what raw-rimmed eye-sockets, what gum-suppuration and tooth-rot, what cavernous cheeks, what leering lips and hopeless eyes, what pain-twisted faces, what sagging spines, what streeling steps, what filthy ragged raiment covering what ghastly-imagined hideousness of body sickened his beauty-nurtured sight.

Yet with all this putridity and squalor there were not wanting, even in those bygone days, many signs of progress and private enterprise. At every street corner there were loud-speakers which yelled forth news and advertisements. Airplanes circled like great dragon-flies in the sky, squirting out smoke-signals such as: “Read Cumbersome’s Papers”, “Why have a Bad Leg? Try Popham’s Pills”, “Trust the Trusts that Feed You”, “Vote for Coddo”, “To him that hath shall be given. Scripture backs the Trusts”, “Are you Languid? Try Peppo”. But these were but superficial signs of civilisation. If the hero had taken the pains to inquire, he would have learnt that every foot of land in the neighbourhood was worth fabulous sums of money; and that by a miracle of organisation every square inch of rag on the backs of the people, and every crust fermenting in their bellies had helped to make millions for somebody. Cúchulainn, however, was too preoccupied with the uglier side of things to make any such inquiries. Was he not a morbid ghoul and gloomy pessimist thus to nose and grope in the dark for hidden horrors, with the best of life dancing before him in the warm sunshine?

In the pother and hurly-burly I have described, owing to the celestial vigour of Cúchulainn, which was chafed rather than impaired by his catatheosis, and to the enfeeblement of the Philosopher, in whom the milk and cheese had not yet replenished the loss of tissue occasioned by his fast, the two became separated, Cúchulainn pursuing his way alone, and the Philosopher, after a vain attempt to overtake him, returning to his lodging. Cúchulainn, however, not perceiving the loss of his companion, strode onward with more than earthly vigour, to the grave detriment of his borrowed body, which was thereby shaken up, loosened, and derivetted, like a cheap car fitted with a too powerful engine, so that soon the stomach of Robert Emmet Aloysius O’Kennedy began to clamour for more nutriment.

Just as this clamour was beginning to be unbearable, Cúchulainn espied a shop window most alluringly arrayed, with a cargo more varied and of more diverse origins than ever was carried by Venetian argosy or Corinthian trireme or galley of Tyre or ancient Sidon. There were oranges there from Jaffa and Seville, and little golden tangerines from Africa nestling in silver tinfoil. There were lemons from Italy and Spain; olives and currants from the land of Hellas; raisins from the Levant, and sultanas and muscatels. Figs were there from Smyrna, and dates from Morocco, Tripoli, and Cyrenaica; bananas, the long straight kind, from Jamaica, and short curved ones from the Canaries; and pineapples and cocoanuts from the islands whose palm-trees fan the Pacific. Then there were cheeses of a hundred species: great Stiltons like mouldy casks from a tangle of jetsam; Gorgonzola streaked like marble; rich yellow English Gloucester; Dutch cheeses like bloated beetroots; hygienic cheeses done up in jars to keep in the vitamines; evanscent-flavoured Gruyere and sharp-fanged Roquefort; simple chaste Cheddar, and sensuous Camembert. There were teas also from China, India, and Ceylon, coffee from the East Indies, cocoa from Brazil and Ecuador, and sugar from five continents and a hundred isles. Rice was there from many lands — China and Japan, Persia and Siam; and with it were pearly sago and slippery tapioca. There were tinned sardines there from France and Scotland; tinned salmon and potted meat from America. From Canada there was shredded wheat and macaroni; and macaroni also from Italy. Great pyramids of apples there were, from England and from the home orchards: some red as the blush of a country maiden, some yellow like shining taffety; with pale Newtown pippins and quiet green baking apples. Over all hung fine well-smoked hams and bacon flitches from Denmark (with a few from Limerick), and American bacon like greasy tallow. And there were biscuits and chocolates and candied fruits and nuts and odds and ends from the Lord knows where. All these things came as tribute to the men of Eirinn: they made nothing for themselves.

Here, therefore, Cúchulainn turned in that he might find the wherewithal to appease the revolt of the baser nature he had put on; but he had scarce set foot in the shop before he was accosted by a large and ferocious person with stand-up hair and waxed moustaches, who, hauling him forward by the lapel of his coat, bawled into his face: “What’s the meaning of this, you blasted young slacker? An hour late! You can leave this day week; and go behind the counter this minute and make up the orders or I’ll smash your face in.”

“Sir,” said Cúchulainn, “I know not what your rank is, nor what you take me for. Howbeit, I am not used to being handled thus, or being spoken to in such fashion as you have assailed me withal. Loose me, therefore, lest the grossness of this body which I am wrapped in should foul my spirit with thoughts of anger.”

The Manager, however, had not in all his life been conscious of the image of God in any shop boy: neither were his eyes opened now. Therefore, taking a stronger hold of Cúchulainn, he would have thrust him ignominiously before him, had not the hero, by a sudden exertion of his muscles, maintained himself as if rooted to the floor.

“Come on, now, you obstinate young devil!” cried the Manager, giving him a flip on the ear with his great fat hand.

Anger came on Cúchulainn at that, and a terrible appearance came over him. Each hair of his head stood on end, with a drop of blood at its tip. One of his eyes started forth a hand’s-breadth out of its socket, and the other was sucked down into the depths of his breast. His whole body was contorted. His ribs parted asunder, so that there was room for a man’s foot between them; his calves and his buttocks came round to the front of his body. At the same time the hero-light shone around his head, and the Bocanachs and Bananachs and the Witches of the Valley raised a shout around him. For such was his appearance when his anger was upon him; as testify the Yellow Book of Leccan and the other chronicles; which, if any man doubt, let him search his conscience whether he have not believed even stranger things printed in newspapers. For myself, I think the chroniclers are the more trustworthy, as they are certainly the more entertaining; for, if they lie, they lie for the fun of it, whereas the journalists lie for pay, or through sheer inability to observe or report correctly.

Now when the Manager of MacWhatsis-name’s grocery saw Cúchulainn facing him in the same dreadful guise wherein he overcame Ferdiad at the ford and drove Fergus before him from the field of Gairech, the strength went out of his limbs, and the corpuscles of his blood fled in disgraceful rout to seek refuge in the inmost marrow of his bones. Dreadful were the scenes that were then enacted in the arched and slippery dark purple passages of his venous system. Smitten with a common panic, Red Cells, Lymphocytes, and Phagocytes rushed in headlong confusion down the peripheral veins, which soon became choked with swarming struggling masses of fugitives. Millions of smaller Lymphocytes and Mast Cells perished in the crush, but the immense mobs poured on towards the larger vessels. Yet even here there was no relief: for as each tributary stream ingurgitated its protoplasmic horde, these too became stuffed to suffocation; so that, though every corpuscle strove onward with all his strength, the jammed and stifled cell mass could scarce be seen to move. Here and there bands of armed Phagocytes, impatient of delay, tried to cut themselves a passage through the helpless huddled mass of Lymphocytes and Platelets: but they succeeded only in walling themselves up with impenetrable mounds of slaughtered carcases. Still more frightful scenes occurred when two mobs, travelling by anastomosing vessels, met each other head to head: for while those in front fought in grim despair for possession of the road until it was totally blocked and thrombosed with their bodies, the cells behind, still harried by fear, pressed onward as vigorously as ever, to the great discomfiture of the dense crowds packed between, who, thus driven by an irresistible force against an impenetrable obstacle, perished in millions.

Thus was the Manager’s blood very literally curdled. And straightway Cúchulainn made his salmon-leap and fisted him a smasher under the third waistcoat button, breaking four of his ribs, and hurling him backwards against the counter with enough force to crack the front of it; yet he was so well covered behind that he took no further hurt, though by his screams you would have thought he had been dumped upon the hob of hell. Then, having wrecked the shop and all it contained, Cúchulainn went forth into the street, breaking a thigh or a collar-bone for any that attempted to stop him: for all which he was most soundly rated by the Philosopher when he returned to him at the close of the day.

“What have I done?” said the Philosopher. “Old footling dunderhead that I am. What have I fetched out of heaven to show mankind his wickedness and folly? Have you no respect for our civilisation that you must sally forth, as fiery-wild as upon that first foray of yours in the barbarous youth of the world, and the first grocer’s shop you come to, must leave your sign of hand upon it as though it had been the Dun of Nechtan’s sons. This will never do. If two thousand years of heaven have not tamed your soul, you must tame it now; or if it is the body of Mr. O’Kennedy that is at fault, then you must bring it into subjection right rapidly: for this sort of thing cannot be done in these days.”

“What,” said Cúchulainn, “have you no such pests now as these sons of Nechtan? whose Dun lay athwart the road out of Ulster into Meath, and they took toll of blood and treasure of all that came by. A right strong place it was, not to be easily taken; and the sons of Nechtan were protected by magic also, so that Foill, the eldest, could not be killed with edge of sword or point of lance; and Tuachel, the second, if he were not killed by the first thrust or the first cut, could not be killed at all; and the youngest, Fandall, was swifter in the water than a swallow in the air: yet I slew them all, and gave their Dun to the winds to howl in, and to the wild beasts of Sliabh Fuaith for a lairage. Have you no such pests now?”

“A many!” said the Philosopher. “Their duns lie across all the ways of the men of Ireland, and none may eat or drink or walk abroad without paying them toll. But they cannot be brought low by such tactics as these: for they are more cunningly fenced in, and protected by more potent magic, than ever were the sons of Nechtan. This Goshawk that I told you of is one of them: and I wish you would learn to control yourself, lest you find yourself in a gaol before you can cross swords with him. But, come now. When you had vindicated your honour by thrashing the grocer, what was your next exploit? Tell me all.”

“When I had left the grocer,” said Cúchulainn, “I walked farther up the street until I came to an eating-house, which I entered very gladly, as I was feeling the pangs of my adopted stomach more keenly than ever. Here I was received at first more courteously than in any other place in this earth of yours. The master of the house bowed low to me, gave me a chair by a table clothed with fine linen, and summoned a servant to attend to my wants. Right generous and goodly fare was then put before me, and I fed full, to the manifest enjoyment of this voracious body. Afterwards, when I had rested me a while, I sought out the master of the house that I might thank him for his hospitality: but in the midst of my speech I was interrupted by the aforesaid servitor, who thrust a piece of paper into my hand, saying, ‘Your bill, sir,’ whereat the master of the house said, ‘Good morning, sir; much obliged; pay at the desk.’ Then there came upon me a most noble rage, not this time out of the spleen of O’Kennedy, but out of my own soul; and I said: ‘Pay! Thou kindless, impious, inhospitable boor! What shall I pay?’ for I had thought the place to be a hostelry for the free entertainment of strangers, such as they have in all the planets I have ever visited, and as they had in Eirinn in the olden time. Then said my host: ‘I don’t know what part of the world you come from, stranger: but in this benighted country you don’t get nothing for nothing.’ ‘Very well, then,’ I said, I will pay. But not now, since I have not the wherewithal. Good day to you, therefore. I will return anon.’ So saying, I would have departed in peace, but the fellow laid hand on my shoulder, saying that he would not suffer me to go until I had paid what I owed. By my hand of valour, my word never was doubted before. Therefore I smote him, yet not very hard: only so as to lay him senseless at my feet, but with the life still in him.” (Here the Philosopher groaned.) “After that,” said Cúchulainn, “two warriors, twins, clad both alike in blue, and their helmets embossed with shining steel, came to his assistance. To these I would willingly have explained the justice of the case, but before I could speak they seized upon me, so that I was compelled to defend myself. Yet, pitying their ignorance, I did them no injury, only binding them back to back with their own harness.”

The Philosopher groaned again, and said: “How many people altogether have you maimed and killed? Speak out. Let me know the worst at once.”

“Venerable sir,” said Cúchulainn, “I maimed no more; neither did I kill any. After that I went to a picture-house, but seeing that there was a charge for admission, I did not enter. And by my hand of valour, there is no other planet in the universe — not even among the savage seventy that revolve around the Dog Star — that acts so scurvily: for pictures were meant to elevate the soul, and therefore cannot be priced.”

“What a pity you had no money,” said the Philosopher.

“After that,” said Cúchulainn, “I entered a car driven by electricity. What do you call them?” “Trams.” “Trams. I thank you. Your trams are tolerable. Nay, I have seen worse, but I have forgotten where. In this tram there were seventeen people, whom I observed with great interest. Nine of them wore discs of glass before their eyes, held in place by a band of metal fixed to the nose. Why did they do that?”

“To enable them to see,” said the Philosopher. “Their eyes were bad.”

“Why?” asked Cúchulainn.

“Civilisation,” said the Philosopher.

“Twelve of them,” said Cúchulainn, “had strange looking teeth of a most unnatural aspect.”

“They were false teeth,” said the Philosopher.

“What became of their own?” asked Cúchulainn.

“Rotted,” said the Philosopher.

“Why?” asked Cúchulainn.

“Civilisation,” said the Philosopher.

“Ten of them,” said Cúchulainn, “had complexions of a pale green colour, with dull eyes and drooping lips. What was the meaning of this?”

“They were poisoned,” said the Philosopher, “by eating too much preserved food.”

“Why did they do that?” asked Cúchulainn.

“They could afford no better.”

“Why?” asked Cúchulainn.

“Civilisation,” said the Philosopher.

“Eight of them,” said Cúchulainn, “had sores on their faces; and there were two that could not sit straight, but balanced themselves tenderly on half a rump. What was wrong with them, venerable sir?”

The Philosopher, with all commendable delicacy, gave explanation of the phenomenon.

Said Cúchulainn: “The bottom of your civilisation is in no better case. Never have I seen so many and such strange diseases as upon this little planet. Yet you have learned and charitable physicians to cure these ills, whose advice was written plain upon the windows of the tram; as, for instance: Are you jaded, weary, dispirited? Have you that tired feeling? Then try Peppo; and, Is your Liver bad? Mixo will set you right; and again. You feel well today. But who knows what loathsome diseases the Future may bring in its train? If you want to KEEP well, dose yourself daily with Absoluto. How is it, then that these diseases persist?”

“These were no physicians’ prescriptions,” said the Philosopher. “They were but the advertisements of the Patent Medicine Trust. All these sick people you saw were sick because they were poor, and so had to stint themselves in food. To pay for these pills and bottles they must stint their food again, and so again become ill.”

“I begin to understand your world,” said Cúchulainn. “While I was making these observations the Guardian of the tram came to me and held out his hand in a manner that I had at last come to know the meaning of. Can you get nothing in this world without money, my friend?”

“No,” said the Philosopher.

“Therefore,” said Cúchulainn, “I got up to leave the tram quietly, whereupon the Guardian laid hand on me as though to detain me. Nevertheless I smote him not, but, stopping, held his arm a moment, so that he paled and offered no further hindrance. Having dismounted from the tram, I accosted one who passed, asking him to direct me to Stoneybatter. Very quickly he gave me a description that I could not understand, and would have hurried away had I not detained him by the shoulder, saying: ‘What, churl! is this your courtesy to a stranger? I have a mind to slay thee, but lead me on straight to Stoneybatter, and perhaps I may pardon thee.’ Said the man of Dublin: ‘What sort of a joker are you? Do you know who I am?’ I said I did not. ‘I am Solomon Beetlebrow,’ quoth he, ‘Minister of the Interior.’ ‘Your humble servant,’ said I, bowing. ‘But time presses, therefore lead on.’ At that I took him by the ear, and in this wise he led me to Stoneybatter, but not without exciting some admiration in our course.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”