King Goshawk (4)

By:

January 19, 2014

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 4: How a Champion took up the Gage of King Goshawk

The Philosopher came upon the spirits of the heroes walking in the meadows of asphodel in Tír na nÓg. They were not like the spirit of Socrates, which resembled a still flame; but they had the forms of men, glorious and ethereal. A hero is a person of superabundant vitality and predominant will, with no sense of responsibility or humour, which makes him a nuisance on earth; but he is in his element in the third heaven. There the heroes take themselves and one another at their own valuation, regarding their weaknesses as strength, their defects as merits. Their life is in their fame: every time an earthly orator recites their names they experience thrills of pleasure; if they are forgotten they die.

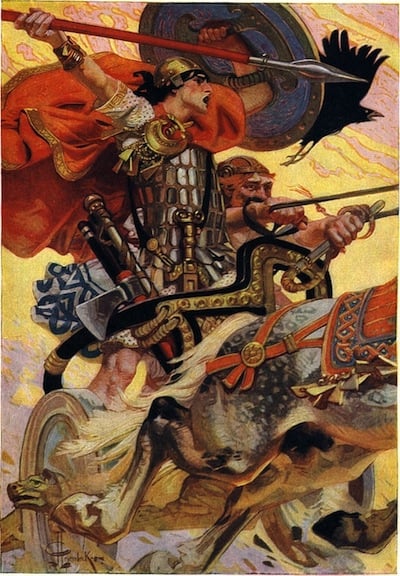

The Philosopher recognised many of the heroes as they walked in golden sunlight over the meadows of asphodel: Hector and Achilles arm in arm; Horatius in friendly colloquy with the Tusculan Mamilius; Henry V. of England; Patrick Sarsfield and Shane O’Neill; Bertrand du Guesclin; Garibaldi; and there were many more whom he did not know, mighty men of every race and nation that has shed blood on the green fields of earth. To none of these did the Philosopher address himself, but ever kept a watch for the one that seemed to him best suited for his purpose: namely, Cúchulainn of Muirthemne, son of Dechtire and of Lugh of the Long Hand, of whom it was said in his time that there was none to compare with him for valour and truth, for magnanimity and courtesy, for strength and comeliness among the heroes of the world. In the crowd that went by there was none that resembled him. The Philosopher therefore passed on, and crossing another field he came to a glade, and saw before him a bush spangled with blossoms of ever-changing colours, that played sweet music in the breath of the wind. In the shadow of the bush reposed a youth of exceeding beauty. Three colours were in his hair: brown at the skin, blood-red in the middle, golden at the ends. Snow-white was his skin; as seven jewels was the brightness of his kingly eyes. Seven fingers had he on each hand; seven toes on each foot; and if you doubt it, go straightway and poke your misbelieving nose into the pages of the Book of Leinster or the Book of the Dun Cow or the Yellow Book of Leccan, where all these things are faithfully recorded, with a good deal more that I spare you. Certain it is that it was by these marks that the Philosopher knew that the youth in front of him was Cúchulainn.

By the hero’s side lay a woman, with her head resting amorously on his shoulder. Very fair she was, with two plaits of hair of the rich hue of marigolds, eyes as blue as the wood anemone, and her naked body as white as the foam of the sea. The Philosopher took her at first to be Emer; but presently in their love talk, which held him entranced as by celestial music, he heard Cúchulainn call her Fand; at which the Philosopher was moved to indignant speech. Said he:

“I thought that affair was over since Manannan Mac Lir shook his cloak of forgetfulness between you. And surely it were only just to render to Emer in heaven that faithfulness you denied to her on earth.”

“You forget,” said Cúchulainn, “that in heaven there is no marrying nor giving in marriage. As for this” — looking down at the woman — “I am tired of it,” whereupon he cast her from him, and she vanished. “She was but the figment of my imagination,” said he, “made with a wish; unmade with another: for heaven is but the fulfilment of the heart’s desire.”

“I do not care for this heaven,” said the Philosopher.

“Your desire is nobler,” said Cúchulainn. “You should seek a higher heaven.”

“I am not a spirit,” said the Philosopher. “I am the mind of a man, and I have come all the way from Earth to find you.”

“What is your errand?” asked Cúchulainn.

“Man,” said the Philosopher, “is full of wickedness and folly.”

“True,” said Cúchulainn. “Tell me what wickedness and folly he has done since I left the earth.”

“In the first place,” said the Philosopher, “he is never done fighting and killing.”

“That,” said Cúchulainn, “is foolish, but it is not wicked. I fought and killed many in my time on earth. I am since convinced of folly, but I am clear of guilt.”

“In those days,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “men fought with men in hot blood, hand to hand, strength against strength, feat against feat, and knowing well what it was they were fighting for. But for many centuries they have been possessed of a devilish powder which enables them to kill at a distance; and by labouring hard at its improvement they have learnt how to kill without seeing one another at all. So that now when countries are at war they do not send forth armies, but each hurls millions of missiles over mountains and seas at the other, destroying lands and cities, men, women, and children, until one or other is utterly overwhelmed. Some of these missiles are so cunningly devised that when they hit they divide up into thousands of particles which riddle and macerate the body; others contain deadly poisons; others scatter the contagion of leprosy and such foul diseases through the air; others on bursting are converted into a fine dust which is borne on the wind and blinds every eye in which it finds lodgement. They inflict on each other besides a thousand more abominations of which I cannot tell you, for already I grow weaker and must soon yield to the earthward pull of my body. But you must know this also, that nobody ever knows the real cause or meaning of these wars, and that if any one asks he is immediately put to silence.”

Said the spirit of Cúchulainn: “This is indeed a most iniquitous way of fighting. But is the tale of man’s wickedness and folly complete?”

“No,” said the Philosopher. “That is only the beginning. While the many are thus fighting, the few are contriving against their liberties, and robbing them of their bread and their homes, so that all the wealth of the world has now passed into the hands of usurers. And at last, infamy of infamies, these have begun to covet the beauty of the world as well.” Then he told Cúchulainn of the bird-purchase of King Goshawk; and at that the hero was thrown into a rage surpassing even that of Socrates. “Enough!” said he. “I will rest here no longer. Let us to earth at once.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”