King Goshawk (3)

By:

January 13, 2014

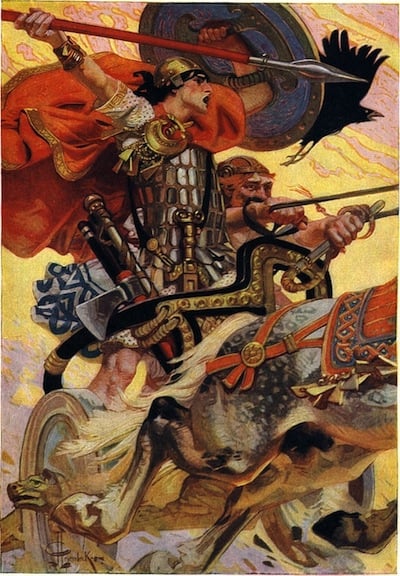

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 3: How the Philosopher, without Mechanical Aid, was translated to the Twentieth Heaven, and held Converse with one who has not spoken by the Ouija Board

The Philosopher, in spite of his years, was of a sound constitution, having at no time eaten when he was not hungry, or drunk when he was not thirsty, as does your ordinary sensible person to the detriment of his liver and the enlargement of his belly. He was not long, therefore, in recovering from the hurts he had suffered at the hands of the citizenry; in whose blows indeed there was more malice than strength, more will than power to do injury. As soon as his mind had regained its vigour and clarity, he said to himself: “So I was right after all.” And when he was fully healed and able to regard the matter with complete impersonality he confirmed that judgement. “And alas,” he said, “it is beyond my power to remedy this evil, for if I speak to the people again they will only treat me as before, to the undoing of their souls.” He began, therefore, to ponder how man might be redeemed from the course of wickedness and folly by which he was travelling to destruction; and to that inquiry he devoted the full labour of his mind for a period of thirty days; at the end of which time he came to the conclusion that the task was beyond the power of mortal man, and could be accomplished only by one returned from the life beyond.

Then the Philosopher set himself to recall to memory the words and works of the great men of the past, in order to discover which of them would be the most fitting to invoke for the purpose: whether Zoroaster or Confucius or Socrates or Plato or Aristotle or Aquinas or Descartes or Hegel or Ibsen or Mill. After prolonged cogitation and a most scrupulous weighing and comparison of the faculties, dispositions, and accidental circumstances of each (and indeed of many others whom he also considered), his choice fell upon Socrates as being the most distinguished of all the wise men for charity and equanimity; as was shown by the answer he gave Xanthippe one day, when, after rating him soundly for his gadabout habits, the low company he kept, and the talk he excited among the neighbours, she was so irritated by his refusal to answer back that she threw a bowl of soup over him: whereat “After the storm,” said he, “we may expect some rain.” The Philosopher felt that only by such a spirit as this could reason be restored to the counsels of mankind, and he made his decision accordingly. As to a way of carrying it into effect, that did not seem to him a matter of overwhelming difficulty; neither did he spend any time devising such methods as those by which Odysseus and Aeneas penetrated to the infernal regions, nor those by which Cyrano de Bergerac, Mr. Cavor, and the members of the Gun Club travelled to the moon; for he well knew that the mind of man can conceive more devices than the powers of his body can execute; on which account he was resolved to set his mind upon the quest alone, and to leave his body behind if need were. Locking himself, therefore, in his room, that he might not be disturbed, he gave his thoughts wholly to Socrates for the space of three days and three nights, during which time also he neither ate nor drank; whereby, as he became purged of earthy matter and gross desires, his mind was set free to journey among the stars, until at length it found the spirit of Socrates wandering in a valley of austere beauty lit alternately by twin suns, red and blue that whirl in the outer regions of space.

Said the spirit of Socrates: “Who are you?”

“One,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “who is looking for Truth.”

“So am I,” said the spirit of Socrates.

“What?” said the mind of the Philosopher. “Is the Truth not to be found in heaven?”

“Only this truth,” said the spirit of Socrates: “that it is not to be found. And this we learn when we come to the twentieth heaven, which is here. For in seeking there is life; but in finding there is stagnation, and stagnation is death.”

“That,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “does not seem to me to be just or reasonable.”

“It is plain, then,” said the spirit of Socrates, “that you have come here direct from some corporeal world, and not from one of the lower heavens. Know then that the justice of heaven is this: that we obtain our desires. Now the desire of the many is for peace; and there is no peace but in death. But the desire of the few is for knowledge; and knowledge is infinite; so that its pursuit is life everlasting. But tell me — for I must not reveal the secrets of paradise — what is your errand?”

“Man,” said the Philosopher, “is full of wickedness and folly.”

“He always was,” said the spirit of Socrates.

“Nay, but,” said the Philosopher, “he had not always the powers of which he is now the master; which indeed are so great that a wise and just people could not safely be entrusted with them, and in his hands are likely to bring him to utter destruction.”

Said the spirit of Socrates, pausing in the middle of the valley of austere beauty, bathed in the purple twilight of the rising and setting suns: “If so, so good; for there is no more use for him.”

“Nevertheless,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “I wish to save him. For we are of one blood, and I cannot but love him.”

“Save him, then,” said the spirit of Socrates, “but do not interrupt my contemplations with any further talk of his follies.”

“I cannot save him,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “because he will not hear me. Therefore I came here to ask you to speak to him instead, for he would listen to one from beyond the grave.”

“I have greater work than that before me,” said the spirit of Socrates.

“It is your own kin,” said the mind of the Philosopher, “— maybe your own descendants — that I want you to save.”

“I am beyond love and hate,” said the spirit of Socrates.

Said the mind of the Philosopher:

“There was a rich man once who owned mines and factories and lands without number; and he had twenty palaces and thirty motorcars. His fingers, which were as fat and flabby as white puddings, were covered with diamond rings; a most impious practice, for precious stones were made for the adornment of beauty, not for the extenuation of ugliness. He had five chins, and his belly was of obscene proportions and very foul within. For this man was a most insatiable eater and drinker. His meals followed so hard upon one another that he had never in all his life known what it was to feel hungry; and it is even reported that in the night hours his attendants administered nutriment to him while he slept, but whether by injection or inunction I cannot tell. Neither was he ever known to take any exercise, but in the most trivial and intimate actions was assisted and forestalled by the attendants aforesaid. Can you picture him so? Pah! what a parcel of tripes was this, to be so carefully handled and so honourably observed by decent men.

“There was also living at this time a poor widow, who had nothing at all but one only son, whom she supported by working in one of the rich man’s factories; for which work he paid her as little as he could, charging her mightily for the kennel he assigned her for a habitation, and for the clothes and food she bought in his shops. Those who have little want less than those who have abundance; and this woman wanted nothing but the happiness of her son, whom she loved with every fibre of her body and every power of her soul. When she looked at him sometimes sleeping in his bed her heart would stand still for very love, and she yearned to take him back to her and enfold him again in the warmth of her being. ‘God bless him: God bless him!’ she would say, and then go and darn his socks or patch his breeches with fingers weary with toil.

“The youngster loved her too, but easily, as is the way of boys. Under her care he grew up strong, handsome, and intelligent. For his sake she denied herself every comfort, and by diligent saving she was able to keep him on at school beyond the age at which the poor are usually taken away from it for the better preservation of their inferiority. Then when she saw with what zeal he applied himself to learning, and when she looked with eyes of loving pride at the growing shelf-ful of prizes he brought home to her, a new pleasure came into her life: that of dreaming golden dreams of her dear boy’s future.

“One day the rich man, wishing to add a few more millions to his wealth, bought up all the sugar in the world and doubled the price. The shopkeepers promptly quadrupled it, and forthwith there arose such an outcry of indignation that the Government was forced to appoint a Commission to inquire into the matter. The rich man bought the souls of the Commissioners, and then, to divert public attention from the question, he purchased an oil-field in a distant part of the world where the frontiers were not very clearly defined, and by manoeuvres which I shall not particularise, as I had not the wit to understand them, presently succeeded in involving the two governments concerned in a war which soon spread over the whole world.

“After two years of warfare the rich man’s country was in terrible straits for men and money; and the Government, knowing that the poor were already taxed to the last penny that could be got from them without violence, decided to levy a special tax on the rich. And they took from the rich man of whom I am telling you nearly six million pounds that year, leaving him barely two millions for himself, less than a quarter of what he was used to; and they also took ten of his motor-cars to carry the wounded from the battle-fields, and one of his palaces to house them; at which the rich man grumbled exceedingly. ‘O misery!’ said he. ‘O my cars and palace! O my two paltry little millions!’ and he began to cry, shedding great lardy tears as big as new potatoes into a golden cup proffered by the attendants. This outburst of grief was followed by one of anger. ‘I am robbed,’ said he. ‘Plundered and oppressed by a tyrannical Government. What is the meaning of this differentiation against one class when all should be united in the national emergency? Why do they not tax tea and sugar, that the common burden may fall on the common shoulders?’ By which meditations he worked himself at last into such a frenzy of indignation that his bile broke all the dams of his liver and flooded his guts, so that he would have burst then and there had not the two doctors, who were always in attendance on him, made a lightning diagnosis, and by operating on him forthwith, saved his precious life. So the rich man lived, and continued his grumblings.

“But being also short of man-power they called up all the lads who were old enough to die: namely, those who were seventeen years and over. And they took the widow’s only son, and drilled him, and taught him how to shoot, and sent him out to the war, where, after he had slain several other women’s sons, he was killed in his turn. Then the light went out of his mother’s life; yet though she had nothing left to live for, she lived on. But they compensated the rich man for the motor in which the boy was carried from the field, and for the palace in which he died.”

Said the spirit of Socrates: “I am also beyond anger and pity.”

“Nevertheless…” began the Philosopher.

“What?” said the spirit of Socrates. “Do you ask me to leave the pursuit of truth and the contemplation of God to endure again the wickedness, ignorance, and folly which I so thankfully left behind me?”

“I have not finished yet,” said the Philosopher. “This pestilent, gross, lardacious fellow, who already owns all the wheat in the world, and all the sugar, as I have told you, has even now, out of the plenitude of his coffers, bought up all the song-birds, and proposes to cage them, and charge a fee to those who would hear them sing.”

At these words perturbation ruffled for the first time the celestial serenity of the spirit of Socrates; and the anger that shook him rolled forth in thunder that rocked the stars in their courses; for, as the poet says:

A robin redbreast in a cage

Puts all heaven in a rage.

But presently, being calmer, he spoke, saying:

“You should not have come to a philosopher on this errand, nor to any of those who inhabit the higher heavens. A hero would better have served your turn. Follow me.”

Then he led the mind of the Philosopher forth from the valley of austere beauty to the rim of the encircling hills, and he showed him the sky suffused with a twilight of purple splendour, with a few great stars shining like sapphires, and a thousand pale nebulae glimmering feebly like phosphorescence on the seas of earth. And he said: “These stars are the heavens; and those nebulae are the material universes. See that dim one yonder of the size and shape of a man’s thumb: that is the universe from which you have come. Lost in its texture are Sirius and Aldebaran and the Pleiades and the Hyades and the inconsiderable sun whose dust is the planets of which your earth is one.

“Now see yonder star of golden hue, lying low on the horizon. Two planets have it for sun, of which the inner is the third heaven, which is Tír na nÓg. There you may find one to help you…. No, do not stay to thank me, but take yourself out of my contemplations with what speed you can.”

The blue sun set, and the red sun rose in a blaze of glory; but to the mind of the Philosopher they were already fused to one purple star as he sped through the black resistless ether of the infinite void. Other stars opened up before him into double, triple, quintuple, or sevenfold suns of divers colours, and closed again at his passing. Right across the vault of the heavens he rushed, through black cold eons of space, throbbing with the heavy music of the spheres, till he came within the zone of the golden sun that lighted the plains of Tír na nÓg.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”