Regression Toward the Zine (17)

By:

December 19, 2013

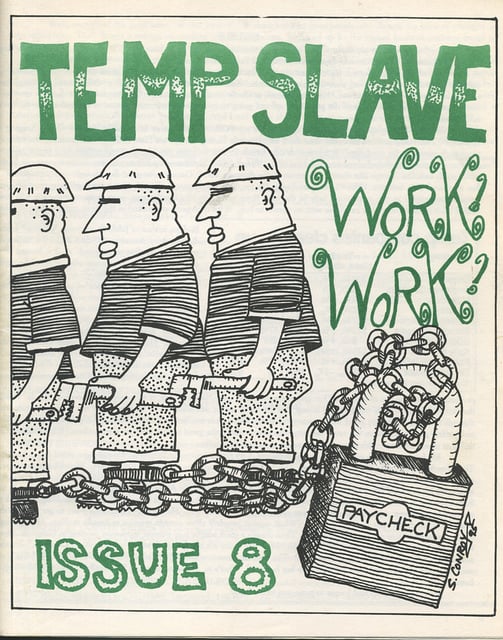

In this installment: Bust, Heinous, McJob, and Temp Slave.

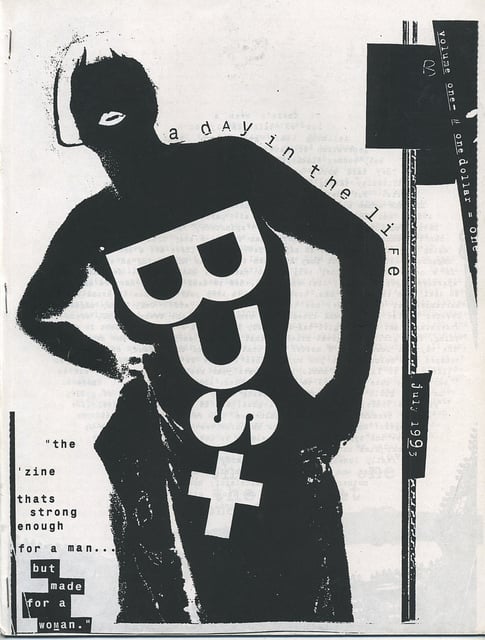

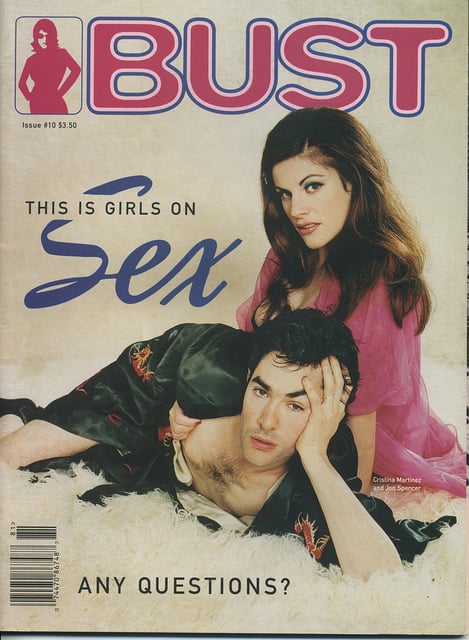

Bust — “for women too old to be riot grrls, too young to have been hippie chicks,” as a review I commissioned for Utne Reader put it, “and way too smart to be labeled anything but feminist” — began in 1993 as a low-budget, third-wave feminist zine. Founding editors “Betty Boob” and “Celina Hex,” who worked at Nickelodeon and wished there was a Sassy for 30-somethings, rapidly evolved Bust into an independent magazine complete with color covers, slick ads, and arty graphics. It’s still going strong today.

Bust cofounder Debbie Stoller (Celina Hex) has also become a best-selling author of hip knitting books.

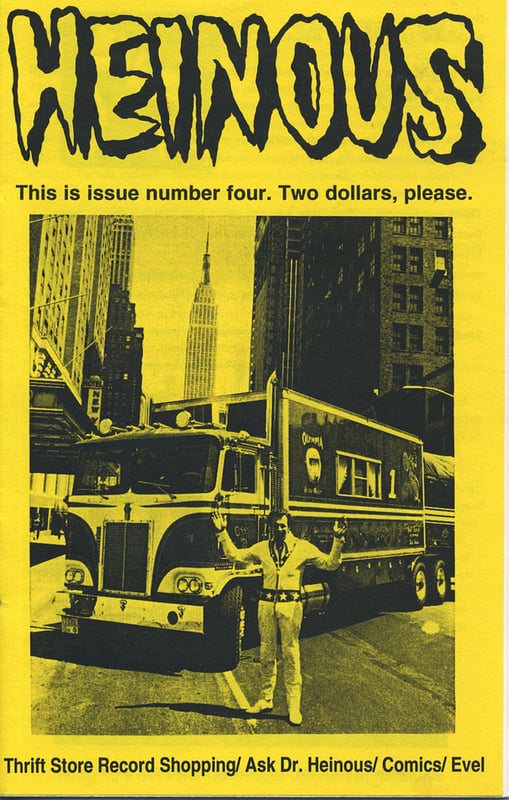

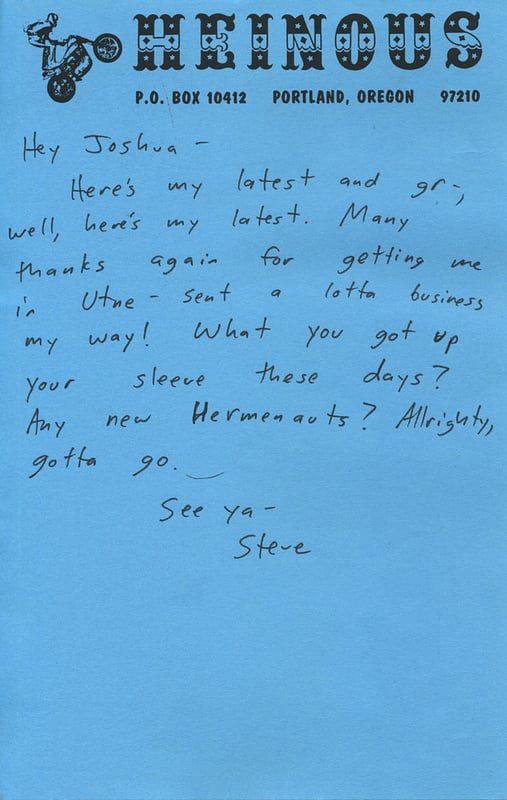

Heinous was published by Steve Mandich out of Portland, Oregon. Ostensibly an Evel Knievel fanzine (as a youth, the publisher styled himself “Stevel Knievel” and did stunts on his BMX), Heinous was also fascinated with Jack Chick’s religious minicomics, 1970s rock monsters, and more. The zine was actually bound with tape from old Stooges and KISS cassettes.

Mandich went on to write a great book about Knievel’s life and legacy. Here’s a Heinous archive.

Julie Peasley published several fun zines — my favorite being McJob, which was by and for the disenchanted employees of low-paying jobs.

Julie has since started the Particle Zoo, selling stuffed protons, neutrons, electrons, quarks, tachyons, and other subatomic particles.

Temp Slave, published by Jeff Kelly (Keffo) out of Madison, Wisc., provided a voice for disgruntled temp workers. In 1997, Keffo published a book version of the zine. Temp Slave was righteously angry — because if wage slavery is bad, temp work is worse. But it was mostly funny — lots of gallows humor, slackery, workplace sabotage, and the like.

Over the course of the mid- to late 1990s, the Web had the same effect on zine publishing as it will in the next few years have on book and magazine publishing: Zine publishers were forced to choose between creating beautifully designed and printed artifacts or going entirely digital. The Web offered free publishing and distribution; after the Web happened, it didn’t make sense to spend a fortune printing and mailing zines when your potential audience could find the same sort of “content” online. Zines had to offer something that blogs couldn’t: a unique tactile and aesthetic sensation. Form became critical.

In the early 1990s a host of zines — including Rollerderby and Bust — began sprucing up their act. If the Zine Revolution was a mannerist phase of DIY publishing, we’d now entered a baroque phase. Those who equate DIY authenticity with crude packaging were scornful. But those of us who were adding color covers, selling ads, and so forth were just trying to make a living doing what we loved. Which meant we needed to sell more copies, more subscriptions, and more advertisements.

Thousands of zines were published after 1993, yet I date the Zine Revolution’s demise to that year specifically. Why? Because in 1993, the Mosaic web browser gave everyone access to the World Wide Web; in 1994, Justin Hall popularized the “web log.”

Like Wile E. Coyote running off the edge of a cliff but not realizing it right away, we zinesters kept working furiously — it seemed like we were gaining traction in the culture! — but no matter how spruced-up our zines became, we were already obsolete.

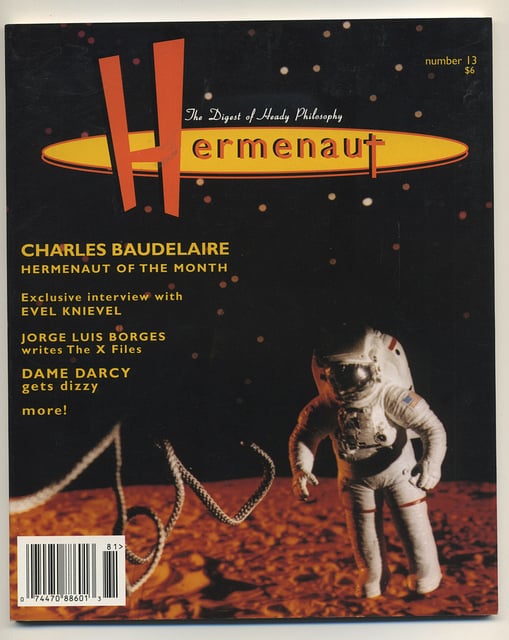

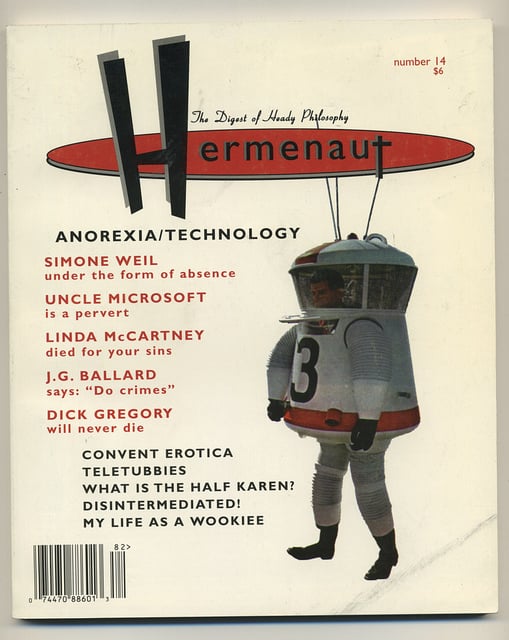

This is a 25-part series in which HiLobrow editor Joshua Glenn, who from 1990–93 published the zine Luvboat Earth and from 1992–2001 published the zine/journal Hermenaut, bids a fond farewell to his noteworthy collection of zines, which he recently donated to the University of Iowa Library’s zine and amateur press collection. CLICK HERE to view the online finding aid for this collection.