101 Sci-Fi Adventures

By:

November 7, 2013

Recently, I compiled a list of two hundred of my favorite adventures published before the Eighties (1984–1993). Forty-three of the titles on that list are science fiction adventures. Also, via the following posts — Best 19th Century Adventure (1805–1903) | Best Nineteen-Oughts Adventure (1904–1913) | Best Nineteen-Teens Adventure (1914–1923) | Best Twenties Adventure (1924–1933) | Best Thirties Adventure (1934–1943) | Best Forties Adventure (1944–1953) | Best Fifties Adventure (1954–1963) | Best Sixties Adventure (1964–1973) | Best Seventies Adventure (1974–1983) — I listed another two hundred and fifty of my favorite adventures. Fifty-eight of the adventures on those secondary lists are science fiction.

Thus — below, please find a list of one hundred and one of my favorite science-fiction adventures — arranged not qualitatively (which would be impossible) but chronologically. The forty-two titles marked with an asterisk (*) are from my Top 200 Adventures list; the others are second-tier favorites.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

Several prefatory notes about the following list: (1) Many great science fiction novels — Walter M. Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, for example — aren’t what I’d call adventures; so no matter how much I admire and enjoy such books, they’re not on this list. (2) The fact that my Top 200/450 lists attempt to name the best adventures of every genre from each decade is a distorted lens through which to view science fiction. The “second-tier” titles listed here are amazing; they were pushed out of the top tier by adventures from other genres (e.g., crime, espionage, horror, picaresque). And during the Thirties and Forties, when so many amazing non-sf adventures were published, there aren’t many top-tier sf adventures listed either. (3) Much as I like many science fiction titles published during the genre’s so-called Golden Age (1934–63), as my list makes apparent, I’m more interested in its Radium Age (1904–33) and New Wave (1964–1983) eras, not to mention its 19th century Poe/Verne/Wells era. (4) I like more than the 101 science fiction adventures listed here; click on the decade-specific links above, then scroll down to the “EVEN MORE” sections. (5) My list of Best Adventures ends in 1983, so obviously it’s incomplete. (6) I haven’t read every science fiction adventure ever, and I’ve probably forgotten some great ones that I have read.

PS: The terrific science fiction website io9.com has reprinted this list. Here are a few responses to thoughtful queries (I’ve paraphrased) from io9’s readers. “Is this an objective list?” That would be impossible. “What’s your definition of ‘adventure’? Shouldn’t it involve running, jumping, shooting? Philip K. Dick, Kafka, Samuel R. Delany, Karel Čapek, Anthony Burgess, George Orwell didn’t write adventures.” My definition of adventure is a reader-response thing: Did it make my pulse race? The novels on this list meet that criterion. “Aren’t some of these novels fantasy?” Yes, some of the sf titles on this list are also fantasy; and some of the titles on my fantasy novel list are also sf.

“Why no Asimov?” Asimov’s books are well worth reading, but they don’t make my pulse race; also, he wrote during sf’s so-called Golden Age, an era that’s barely represented here for reasons noted above. “Why no Clarke, Campbell, Blish, Vance, Zelazny, Matheson [other Golden Age sf authors]?” I’m a fan! Please see prefatory note #3 above. “Why no Heinlein juvies?” I’m a Heinlein juvie fan; I’m disappointed by their exclusion too. NOTE: Since compiling this list of 101 sf adventures, I’ve also put together a list of my 75 favorite Golden Age sf adventures — which corrects for some, though not all of the omissions mentioned above.

“Why no sf after 1983?” I like a lot of it! But my Top Adventures List project stops in 1983, because: I’m far more widely read in pre-1983 adventure; I have friends who’ve published adventures since 1983, and I don’t want guilt to be a factor; plus, adventure fans already know which post-1983 books are great. “Why no pre-19th century sf?” My Top Adventures List project begins in 1805; although pre-19th century sf is important historically, I don’t love reading it.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

In chronological order, here is the list of my Top 101 Science Fiction Adventures:

- 1818. Mary Shelley’s Gothic science fiction adventure Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. From multiple points of view, we read about a brilliant scientist and his creation: a dehumanized creature who longs for love and friendship and, eventually, revenge. PS: There are two editions of the book; the 1831 “popular” edition was heavily revised and tends to be the one most widely read; scholars tend to prefer the 1818.

- * 1838. Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic sea adventure The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Poe’s only complete novel — about a teenager who stows away on a ship, is kidnapped by mutineers and pirates, encounters cannibals, and explores the Antarctic before discovering the key to all Western mystical traditions — has been described as “at once a mock nonfictional exploration narrative, adventure saga, bildungsroman, hoax, largely plagiarized travelogue, and spiritual allegory.”

- * 1870. Jules Verne’s science-fiction adventure Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea introduces us to Captain Nemo, a scientific genius who roams the depths of the sea in his submarine — in quest of treasure, knowledge, and revenge. NB: The book inspired Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “Le Bateau Ivre.”

- * 1874. Jules Verne’s science-fiction Robinsonade The Mysterious Island. An engineer, a sailor, a young boy, a journalist, and an African American butler escape a Civil War prison in a hot air balloon and crash land on a Lost-type island in the South Pacific. Who is observing them, helping them? Marred by didactic lessons of all sorts.

- 1895. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Time Machine.

- * 1896. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Island of Doctor Moreau. Edward Prendick, a shipwrecked man, is left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, who creates human-like beings from animals. After Moreau is killed, the Beast Folk begin to revert to their original animal instincts.

- 1897. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The Invisible Man. A scientist invents a way to change a body’s “refractive index” so that it absorbs and reflects no light. Experimenting upon himself, he becomes invisible… and plans a reign of terror. A great hunted-man type thriller: How do you catch an invisible man?

- * 1898. Alfred Jarry’s ’pataphysical adventure Gestes et Opinions du Docteur Faustroll, Pataphysicien. Faustroll and his monkey butler travel around Paris — on a mythical register — in a high-tech boat/vehicle. Published posthumously, in 1911.

- 1898. H.G. Wells’s science fiction adventure The War of the Worlds.

- 1901. M.P. Shiel’s science fiction adventure The Purple Cloud.

- 1904. G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Napoleon of Notting Hill, in which battles rage between neighboring boroughs of London.

- * 1905. Rudyard Kipling’s Radium Age science fiction adventure With the Night Mail follows the exploits of an intercontinental mail dirigible battling a storm. Also, we learn that a planet-wide Aerial Board of Control (A.B.C.) now enforces a technocratic system of command and control in world affairs. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- 1905. Edwin Lester Arnold’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation. It’s Gulliver’s Travels in space.

- 1908. H.G. Wells’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The War in the Air.

- 1908. Gustave Le Rouge’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars. Sequel: La Guerre des Vampires (1909).

- 1911. J.D. Beresford’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Hampdenshire Wonder, one of the first science fiction books about a hyper-intelligent mutant child.

- * 1912. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Lost World. The brilliant Prof. Challenger and companions journey to a South American jungle, where they discover a plateau crawling with prehistoric monsters. The first popular dinosaurs-still-live tale!

- * 1912. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Radium Age science fiction adventure A Princess of Mars. Inspired by the Mars-is-dying speculations of astronomer Percival Lowell (and perhaps by Edwin Lester Arnold’s 1905 Lieut. Gullivar Jones), this is a truly epic “planetary romance.”

- * 1912. Jack London’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Scarlet Plague. A former UC Berkeley professor recounts the chilling sequence of events — a gruesome pandemic (in 2013!) — which led to his current lowly state. Modern civilization has fallen, and a new race of barbarians, descended from the world’s brutalized workers, has assumed power. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- * 1912. William Hope Hodgson’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Night Land is set on a frozen future Earth whose human inhabitants live in an underground redoubt surrounded by Watching Things, Ab-humans, and other monstrous invaders from another dimension. Praised by everyone from H.P. Lovecraft to China Miéville… but little-read now. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- 1912. Garrett P. Serviss’s apocalyptic sf adventure The Second Deluge, in which complacent scientists, scheming public officials, and capitalist robber barons get their comeuppance after failing to heed a modern Noah’s warnings about an apocalyptic flood. PS: The author was a well-known astronomer.

- 1912. George Allan England’s apocalyptic sf adventure The Vacant World, the first part of the author’s Darkness and Dawn trilogy, in which two modern people wake up a thousand years after the Earth has been devastated by a meteor, and set about rebuilding civilization. New York lies in ruins; the protagonists wake up on the top floor of a ruined skyscraper!

- 1913. J.D. Beresford’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Goslings. When a plague kills off most of England’s male population, the proper bourgeois Mr. Gosling abandons his family for a life of lechery. His daughters — who have never been permitted to learn self-reliance — in turn escape London for the countryside, where they struggle to survive. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- 1913. Arthur Conan Doyle’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Poison Belt. If you alone had discovered that the Earth was about to be engulfed in a belt of poisonous “ether” from outer space, what would you do? Professor Challenger assembles the adventurers with whom he’d once romped through a South American jungle (in The Lost World) and locks them in his wife’s dressing room. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- * 1914. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Radium Age science fiction adventure At the Earth’s Core. A mining engineer discovers — thanks to his “iron mole” machine, that the Earth is hollow; at its center is Pellucidar, a land (lit by a miniature Sun) in which stone-age humans are dominated by intelligent flying reptiles… and in which prehistoric creatures roam freely. NB: H.P. Lovecraft was a fan; check out his 1931 adventure At the Mountains of Madness.

- 1914. G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Flying Inn. In an alternate future, England is dominated by Islamists who have banned alcohol. Humphrey Pump and Captain Patrick Dalroy roam the country selling rum, dispensing cheer to the workmen who have been denied a drink, and singing. Eventually, they must foil an Islamist coup!

- 1914. Raymond Roussel’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Locus Solus, an ironic homage to the Robinsonade. A scientist invites colleagues to his country estate, where he shows them his bizarre inventions.

- 1914. H.G. Wells’s apocalyptic Radium Age science fiction adventure The World Set Free.

- * 1915. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s utopian Radium Age science fiction novel Herland. A utopian novel describing an all-female society (with reproduction by parthenogenesis) in which women’s essential quality of nurturing creates a peaceful and rationally ordered world. Mostly exposition, but there are one or two chase scenes — in which the women capture the rogue males. (Read it on HiLobrow.)

- 1915. Jack London’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Star Rover. Laced into a straitjacket by San Quentin prison officials, a convicted murderer enters a trance state — in which he not only projects his spirit into past reincarnations but visits outer space.

- * 1919. H. Rider Haggard’s Radium Age science fiction adventure When the World Shook. When adventurers Bastin, Bickley, and Arbuthnot are marooned on a South Sea island, they discover two Atlanteans in a state of suspended animation. One of the awakened sleepers, Lord Oro, is a superman. The other is Oro’s sexy daughter, Yva. Using astral projection, Lord Oro determines whether or not he should once again employ an infernal chthonic machine to drown the worthless human race! (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- * 1920/1921. Karel Čapek’s Radium Age science fiction play R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots expressed the Czech litterateur’s fear of social disaster and the unlimited power of corporations — and gave the world the term “robot,” which the author’s brother, Joseph, coined (from the Czech for “corvée labor”) to describe manufactured, exploited humanoids.

- 1920. David Lindsay’s Radium Age science fiction adventure A Voyage to Arcturus.

- 1920. Edward Shanks’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The People of the Ruins. Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising in 1924, Jeremy Tuft awakens 150 years later — on the eve of a new Dark Age! When half-savage northern English and Welsh tribes invade London, he sets about reinventing twentieth-century weapons of mass destruction. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- * 1921. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s Radium Age science fiction adventure We. Circulated in samizdat for years — in which form it influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four — this dystopian novel extrapolates from the rhetoric of communists who advocated extending Taylorism, Fordism, and other (capitalist) scientific-management techniques beyond the factory into all spheres of life. It’s set in a totalized social order whose citizens eat, sleep, work, and even make love like clockwork.

- * 1922. Cicely Hamilton’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Theodore Savage. When war breaks out in Europe, British civilization collapses overnight. The ironically named protagonist must learn to survive by his wits in a new Britain… one where science and technology swiftly come to be regarded with superstitious awe and terror. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- * 1922/1926. Franz Kafka’s posthumously published Das Schloss (The Castle). The protagonist, K., struggles for unknown reasons to gain access to the mysterious authorities of a castle who govern the village. Sardonic inversion of an adventure — the protagonist can’t get started. Brian Aldiss writes, of Kafka’s oeuvre: “the baffling atmosphere, the paranoid complexities, the alien motives of others, make the novels a sort of haute sf.”

- * 1922. Karel Čapek’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Absolute at Large describes how a near-future Greatest War (during which worldwide civilization collapses) is sparked by the manufacture of an atomic reactor whose unintended byproduct is the spiritual essence that permeates every particle of matter: i.e., God. An absurdist tour-de-force.

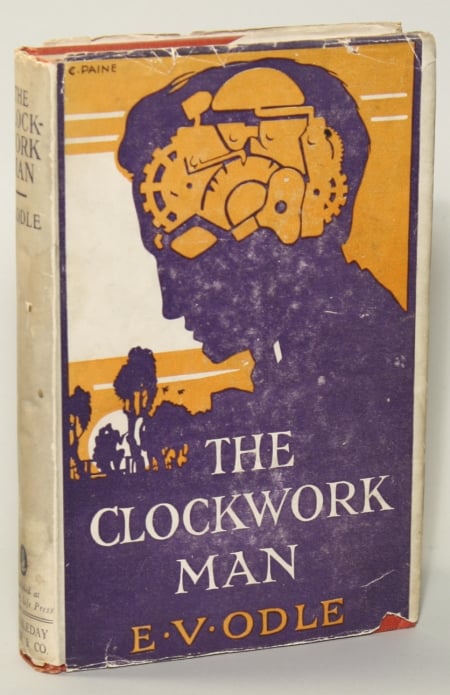

- * 1923. E.V. Odle’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Clockwork Man. Years from now, advanced beings will implant devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, this technology will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live perfectly regulated lives (hello, Singularity). However, if one of these devices should ever go awry, a being from the future might turn up in the 1920s. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

- 1924. Gaston Leroux’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Le machine à assassiner. A human-looking mechanical man is animated by a clockwork expert (presciently named Norbert) with the aid of radioactive serum and the brain of guillotined murderer; the cyborg carries off Norbert’s daughter, only to later save her from… a Hindu vampire cult!

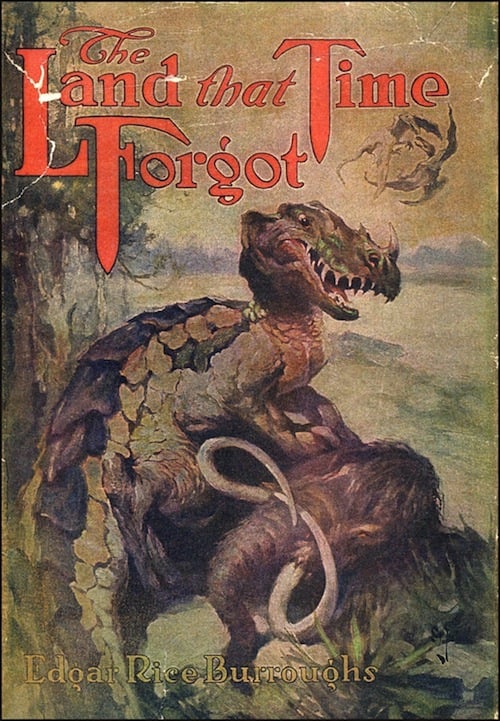

- 1924. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Land That Time Forgot. Many readers consider this Burroughs’s best novel! A submarine is drawn to an uncharted magnetic island… inhabited by tribes in various states of evolution towards Man.

- 1924. S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Amphibians.

- * 1927. Muriel Jaeger’s Radium Age science fiction adventure The Man with Six Senses. When Hilda, a beautiful young member of England’s cynical postwar generation, meets Michael, a hapless mutant capable of perceiving the ever-shifting patterns of electromagnetic fields, she becomes his apostle. (Reissued by HiLoBooks.)

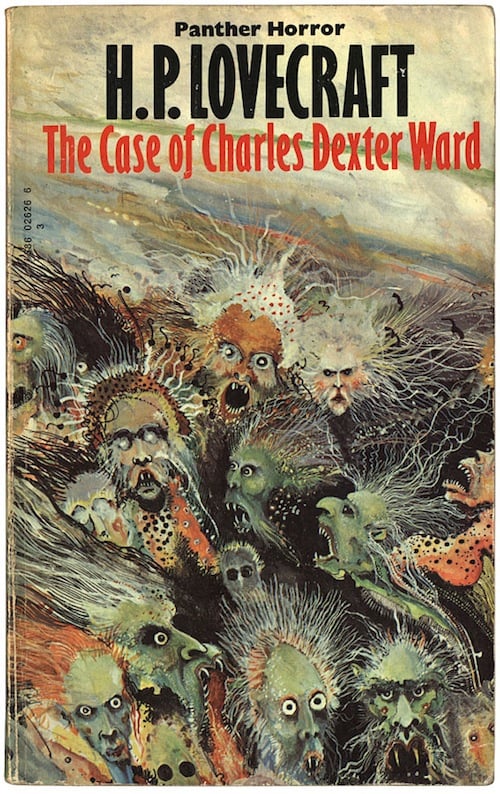

- 1927/1941. H.P. Lovecraft’s occult/sf adventure The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, in which a young Rhode Island man becomes obsessed with his wizardly ancestor.

- 1928. S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Deluge.

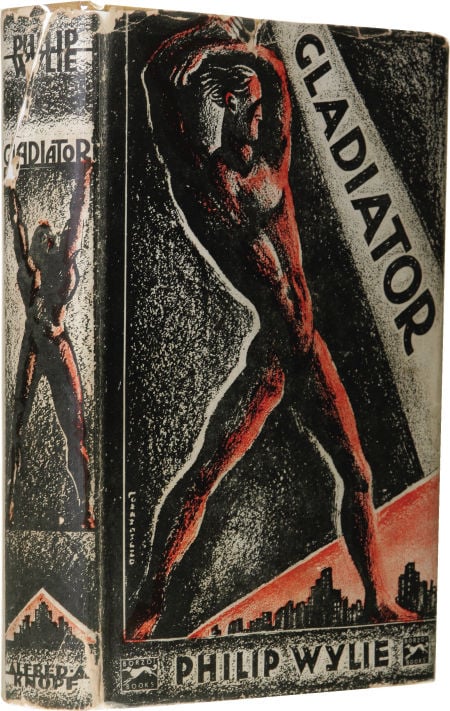

- * 1930. Philip Gordon Wylie’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Gladiator, in which a young man who is nearly invulnerable and can leap trees fights in WWI — as a member of the Foreign Legion. Later, he plans to adopt a secret identity in order to fight crime in New York. A major influence on Siegel and Shuster’s 1938 Superman comic.

- * 1931/1936. H.P. Lovecraft’s Radium Age science fiction adventure At the Mountains of Madness. A team of explorers from Miskatonic U. arrive in Antarctica… where they discover the frozen bodies of ancient monsters. They accidentally thaw one out. Plus, an abandoned city whose technologies reveal the true origins of intelligent life on Earth. Spoiler: It was ancient astronauts.

- 1931. John Taine’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Seeds of Life. An ugly and stupid lab technician is transformed via X-rays into a gorgeous genius. This superman invents wireless energy transfer devices, but does not use them to benefit mankind.

- 1923/1931. A. Merritt’s fantasy/sf adventure The Face in the Abyss.

- 1931/1936. H.P. Lovecraft’s occult/sf adventure The Shadow Over Innsmouth.

- * 1932. Aldous Huxley’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Brave New World. In the year 632 A.F. (After Ford), extra-uterine babies are the norm and conspicuous consumption is the law. Everyone is content… until a Shakespeare-quoting Savage questions whether all this progress is worth it. The one sf novel that everyone knows — and one whose predictions (unlike those of Nineteen Eighty-Four) are uncannily accurate.

- * 1932. Edwin Balmer and Philip Gordon Wylie’s Radium Age science fiction adventure When Worlds Collide. Scientists rescue a group of men and women, and bear witness to the collapse of civilization, just before the Earth is destroyed.

- 1932. Olaf Stapledon’s Radium Age science fiction adventure Last Men in London.

- * 1935. Olaf Stapledon’s science fiction adventure Odd John. Led by the titular teenage mutant “supernormal,” a group of evolved misfits form an island colony, where they experiment with telepathic communication and “individualistic communism.” Don’t kid yourself they belong to you / They’re the start of a coming race!

- 1949. George Orwell’s dystopian science fiction adventure Nineteen Eighty-Four. In a totalitarian social order marked by omnipresent government surveillance, Ministry of Truth revisionist historian Winston Smith dreams of rebellion against “Big Brother.” His illicit romance with the mechanic Julia leads to Smith’s imprisonment, interrogation, torture, and re-education by the Ministry of Love’s Thinkpol. Not exactly an adventure…

- 1950. Ray Bradbury’s science fiction adventure collection The Martian Chronicles.

- * 1951. John Wyndham’s post-apocalyptic science fiction adventure The Day of the Triffids, in which a man whose eyes are bandaged escapes a world-wide epidemic of blindness (caused by a meteor shower). Not only does civilization collapse, but the blind are helpless to resist the depredations of a bioengineered species of plants known as “triffids.” Rival colonies of survivors are formed, some more humane than others.

- 1951. Robert Heinlein’s science fiction adventure The Puppet Masters.

- * 1952. Alfred Bester’s science fiction adventure The Demolished Man, serialized. A police procedural set in harshly capitalistic future world where widespread telepathy has rendered deceit and crime impossible — and privacy a thing of the past. When Ben Reich, a young businessman, decides to murder a rival, he hires an Esper (telepath) to hide his murderous thoughts. Published in book form in 1953. NB: Winner of the first Hugo!

- * 1953. Ray Bradbury’s science fiction adventure Fahrenheit 451. Published shortly after McCarthy’s speech about Communists making policy in the State Department, Bradbury’s best novel takes as its theme censorship and the threat of neo-fascist book burning in the United States. But it’s also an exciting hunted-man tale: Who can forget the robot dog, with its hypodermic snout!

- 1954. Jack Finney’s science fiction adventure The Body Snatchers. Interpreted as a social and political satire on the conformity of the Fifties. Inspired three film adaptations.

- 1956. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure The World Jones Made.

- 1956. Alfred Bester’s science fiction adventure The Stars My Destination, also known as Tiger! Tiger! An interstellar Count of Monte Cristo, and an important influence on Samuel R. Delany’s Nova.

- * 1959. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure Time Out of Joint. Ragle Gumm believes that he lives in the year 1959 in a quiet American suburb. His repeatedly wins the cash prize in a newspaper competition, “Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?”. Confusion gradually mounts for Gumm. Adapted as (actually, baldly ripped off by) The Truman Show. Except Gumm’s occluded reality is much weirder than Truman’s.

- 1960. Poul Anderson’s historical/science fiction adventure The High Crusade.

- 1961. Robert Heinlein’s science fiction adventure Stranger in a Strange Land. A cult classic.

- 1962. Anthony Burgess’s science fiction adventure A Clockwork Orange.

- * 1962. Madeleine L’Engle’s YA science fiction adventure A Wrinkle in Time. Fourteen-year-old Meg Murry is shy, awkward, and too good at math to be considered cool. When their scientist father disappears, Meg and her genius baby brother travel through space and time to rescue him — with the assistance of two weird neighbors (Mrs. Whatsit and Mrs. Who), and a basketball-playing jock.

- 1963–on. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s comic The X-Men.

- 1964. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure Martian Time-Slip.

- 1964. William S. Burroughs’s science fiction adventure Nova Express.

- * 1965. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. Via an odyssey of nested hallucinations, the Gnostic idea that the world is the creation not of God, but of an evil, lesser deity, is burned forever into the reader’s mind. The title character is a demiurge who brings to mankind a “negative trinity” of “alienation, blurred reality, and despair.”

- * 1965. Frank Herbert’s science fiction adventure Dune, a potboiler about one family’s declining empire, a mythology-saturated fantasy about the founding of a new social order, and a band-of-brothers yarn (Thufir Hawat, the human computer; Gurney Halleck, the troubadour warrior; master swordsman Duncan Idaho). It’s also a criticism of humankind’s despoliation of nature in the name of progress. Plus: Alia, a telepathic four-year-old girl, roams the battlefields of Arrakis slitting the throats of imperial stormtroopers! The Bene Gesserit, who subtly guide humanity’s development! The worm-riding Fremen! Wow.

- * 1966. J.G. Ballard’s science fiction adventure The Crystal World. In the Cameroon Republic, a British doctor discovers that entrance to the forest is being discouraged… but he can’t figure out why. Seeking his friends, who run a leper colony, he travels upriver and discovers a forest of glass. Trees, grass, water, animals and men are slowly encased in glittering crystals. The universe, its myriad of possibilities, is crystallizing into sameness. Serialized in the first Moorcock-edited issue of New Worlds.

- 1967. John Christopher’s YA science fiction adventure The White Mountains. First in the Tripods trilogy.

- 1968. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

- 1968. Samuel R. Delany’s science fiction adventure Nova.

- * 1969. Kurt Vonnegut’s science fiction adventure Slaughterhouse-Five. Billy Pilgrim witnesses the firebombing of Dresden in WWII while “time-tripping” to the distant planet of Tralfamadore, where he is put in a zoo and mated with a movie star. Sardonic inversion of the genre; considered the author’s masterpiece.

- * 1969. Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish science fiction adventure The Left Hand of Darkness. A much-admired novel set on a frozen planet whose denizens are neither female nor male: they have gender identities and sexual urges only once a month. When a Terran envoy, Genly Ai, and an exiled native politician, Estraven, escape from a prison together, they battle snow and ice together; and as Estraven changes from male to female, Ai questions the binary assumptions that structure his own worldview. Harold Bloom said, of this book: “Le Guin, more than Tolkien, has raised fantasy into high literature, for our time.”

- 1969. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure Ubik.

- 1970. Poul Anderson’s science fiction adventure Tau Zero. A spaceship is caught in an uncontrollable acceleration. One of the author’s best science fiction novels.

- * 1971. Walker Percy’s satirical science fiction adventure Love in the Ruins. When Sixties-type political and cultural divides lead America to devolve into chaos, a small-town Louisiana psychiatrist sets up a love nest at an abandoned motel — and uses his invention, the Ontological Lapsometer, to diagnose and treat the harmful mental states at the root of the social crisis. “For the world is broken, sundered, busted down the middle, self ripped from self and man pasted back together as mythical monster, half angel, half beast, but no man….”

- 1971. Ursula K. Le Guin’s science fiction adventure The Lathe of Heaven.

- 1971. M. John Harrison’s science fantasy adventure The Pastel City.

- 1971. Robert C. O’Brien’s children’s science-fiction adventure Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH.

- * 1974. Ursula K. Le Guin’s anarchistic science fiction adventure The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia, a pointed critique of typical utopian narratives. It’s set on Annares, a planet whose inhabitants value voluntary cooperation, local control, and mutual tolerance — but who have preserved their grooviness through an entrenched bureaucracy that stifles innovation. Le Guin’s protagonist temporarily abandons Annares for a nearby world, one that is superior in certain respects because its inhabitants value the free market. How to reconcile?

- 1974. Christopher Priest’s science fiction adventure Inverted World.

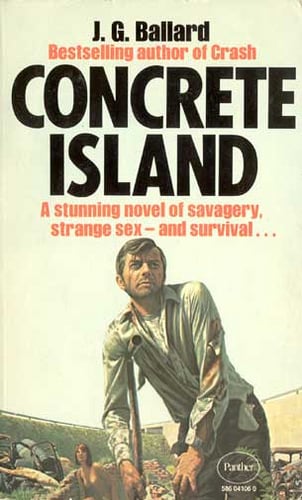

- 1974. J.G. Ballard’s science fiction adventure Concrete Island. A satirical Robinsonade set on an “island” in the middle of a super-highway.

- 1975. Samuel R. Delany’s science fiction adventure Dhalgren.

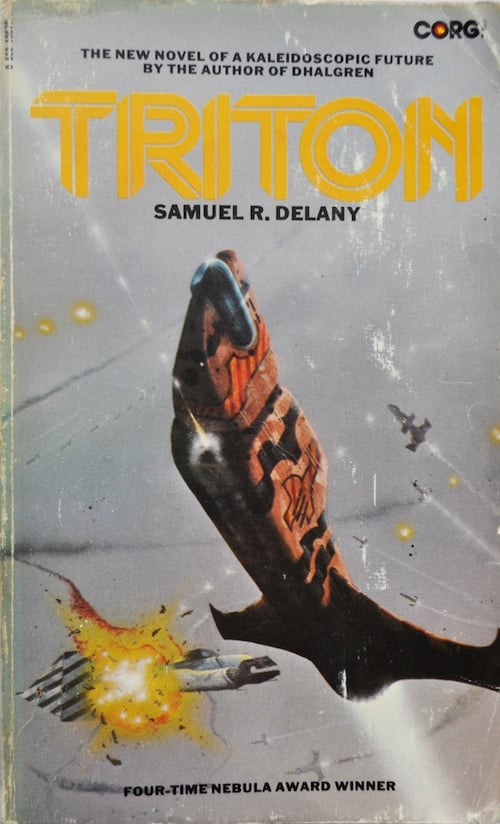

- * 1976. Samuel R. Delany’s Foucauldian science fiction adventure Trouble on Triton: An Ambiguous Heterotopia (also published as Triton). A post-structuralist novel set on a Neptunian colony where no one goes hungry and everyone is sexually confused. The subtitle signal’s the author’s critique not only of utopian narratives but of Le Guin’s vestigial nostalgia for pastoral communes. Political tensions between Triton — where one can change one’s physical appearance, gender, sexual orientation, and even specific patterns of likes and dislikes — and Earth lead to a destructive interplanetary war.

- 1976. Ursula K. Le Guin’s science fiction adventure The Word for World is Forest.

- 1976–79. Moebius’s science fiction graphic novel The Airtight Garage.

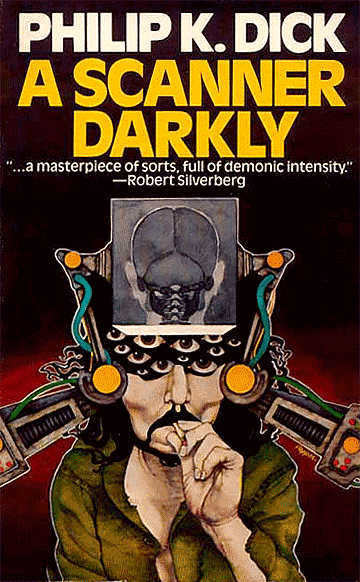

- * 1977. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure A Scanner Darkly. Set in a barely futuristic suburban LA of 1994, Scanner tells the story of “Fred,” a disillusioned narc who enjoys the company of the addicts with whom he lives as “Bob” — whose own drug intake contributes to a toxic brain psychosis complicated by Fred’s new assignment… to spy on Bob. The book ends with a dramatic dedication to Dick’s many friends who’d been killed or permanently damaged by drug abuse; the author’s own name is on the list.

- * 1977–on. Gary Panter’s comic Jimbo. Panter’s “ratty line” illustrations helped define the style of L.A. punk. But the appeal of Jimbo — an all-American, freckle-faced punk wandering through a post-apocalyptic social order on Mars known as Dal Tokyo — is timeless. The first Jimbo comics appeared in the zine Slash and in Spiegelman/Mouly’s Raw; they have been collected in Jimbo (1982), Invasion of the Elvis Zombies (1984), Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise (1988), and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). Panter is still producing Jimbo adventures today!

- 1977. Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s science fiction adventure Lucifer’s Hammer. A cozy catastrophe.

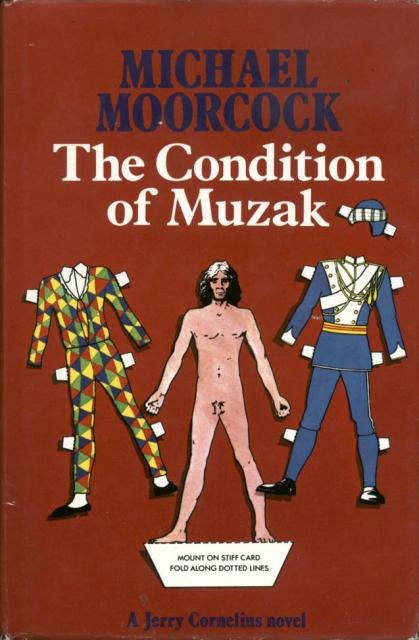

- 1977. Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius science-fiction adventure The Condition of Muzak. The fourth in the author’s Jerry Cornelius Quartet.

- 1978. Philip K. Dick’s science fiction adventure VALIS.

- 1979. Douglas Adams’s absurdist science fiction adventure The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

- * 1980. Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist science fiction adventure Wild Seed. Anyanwu, a 350-year-old shapeshifter who can absorb bullets and heal with a kiss, is lured from an African jungle to the colonies of America by the ruthless Doro, an immortal entity who changes bodies like clothes — and who wants to use Anyanwu for his breeding experiments. The history of slavery, recapitulated as alien abduction! The prequel to Mind of My Mind (1977), Clay’s Ark (1984), Survivor (1978), and Patternmaster (1976).

- 1980. Russell Hoban’s science fiction adventure Riddley Walker.

- 1982. Alan Moore’s graphic novel adventure V for Vendetta, set in a near-future United Kingdom, ruled by the fascist Norsefire Party, which came to power after a nuclear war. An anarchist revolutionary, who wears a Guy Fawkes mask and calls himself “V,” begins a campaign of terrorism designed to bring down the government — and revenge himself on the scientists whose experiments led him to develop superhuman abilities. Illustrated mostly by David Lloyd.

Adventure-wise, the Oughts struggled at first to escape the shadow of the 1894–1903 decade, during which H.G. Wells gave us The Island of Doctor Moreau and The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, Bram Stoker Dracula, Jack London The Call of the Wild, Arthur Conan Doyle The Hound of the Baskervilles, Joseph Conrad Heart of Darkness, L. Frank Baum The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and Anthony Hope The Prisoner of Zenda. A transitional era from the 19th to the 20th Centuries; what rough beast was a-borning? By 1912, a wild new adventure sub-genre — Radium Age science fiction (a term I coined; I’ve written elsewhere about sf’s Radium Age) — had made its mark.

As I’ve written elsewhere, 1912 was one of the most important years in the history of science fiction.

Brian Aldiss laments, in Billion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction, that “It is as difficult to imagine Franz Kafka, Aldous Huxley, Karel Čapek, et al., submitting their works for serialization in Amazing Stories or Weird Tales, as it is to think of E.E. Smith, creator of the Grey Lensman, as a moulder of Western thought. The gulf between two similar sorts of reading matter has become complete.” Not any longer! HILOBROW is bridging that gulf.

During the Thirties, guided in important ways by Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell Jr., pulp speculative fiction’s romantic, uncanny 1904–33 Radium Age era was — for better or worse — eclipsed by the wised-up, gung-ho “mature” science fiction and fantasy of, among others, Robert A. Heinlein, Fritz Leiber, L. Sprague de Camp, Fredric Brown, Clifford D. Simak, L. Ron Hubbard, C.L. Moore, A.E. van Vogt, Eric Frank Russell, Jack Williamson, Robert E. Howard, John Wyndham, and Edmond Hamilton. As you can tell, although I like sf from the genre’s so-called Golden Age, I’m far less interested in it than I am in the sf that came immediately before and after the Golden Age.

The apex of Cold War paranoia coincided with the apex of the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction and Fantasy — by 1963, the New Wave era of these genres was visible on the horizon. Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint and The World Jones Made and The Man in the High Castle, Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, and J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World already contain New Wave elements. Yet they’re not so self-conscious as New Wave science fiction and fantasy; the pleasure they offer to the reader is less rarified and self-conscious than what was to come. Not that there’s anything wrong with rarified and self-conscious.

The New Wave era in Adventure’s science fiction sub-genre began in 1964 (when Michael Moorcock took over the editorship of the British sf magazine New Worlds; Jack Kirby also had something to do with it, in science-fiction comics) and lasted through 1983. (Cyberpunk begins in ’84, with Gibson’s Neuromancer.) What was New Wave? The best sf adventures published during the Sixties were characterized by an ambitious, self-consciously artistic sensibility. Many of my favorites — including Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Martian Time-Slip, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and Ubik; William S. Burroughs’s Nova Express; Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven; Samuel R. Delany’s Nova; and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five — concern themselves, at the level of both content and form, with the nature of perception itself.

If adventure novels in the Sixties troubled their readers’ faith in fixed, universal categories, and in certainty, Seventies adventure replaced these relics with difference, process, anomaly. The science fiction of the era — Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, Samuel R. Delany’s Trouble on Triton, Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, Christopher Priest’s Inverted World, Olivia E. Butler’s Kindred and Wild Seed — was as far-out as it gets, the final flourish of New Wave before the advent of cyberpunk. All binary oppositions (past/present, liberal/conservative, innocent/guilty, utopian/anti-utopian) are overthrown. Ambivalence, indeterminacy, and undecidability of things: In Seventies adventures, these are the anti-anti-utopian new normal.

Postmodernist adventure first began to flourish in the late Fifties (1954–1963), although it was invented earlier than that by Flann O’Brien. The trend reached its apex in the late Sixties (1964–1973). In the Seventies, postmodern lit rallies for a last hurrah. Several great Seventies adventures foreground the eclecticism and hybridity lurking beneath the illusion of conceptual unity and institutional integrity. In Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew, Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada, Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, and John Crowley’s Little, Big, we discover, e.g., the author as character; plots which are self-contradicting or which blur reality and fiction; form and language being disrupted or played with; and fiction that overtly references other fictional works. PS: Although postmodernist literature is still produced in the Eighties, it’s no longer as funny. Unfunny postmodernism… why bother?

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE