The Zayat Kiss (5)

By:

October 9, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the fifth installment of our serialization of Sax Rohmer’s story “The Zayat Kiss.” New installments will appear each Wednesday for six weeks.

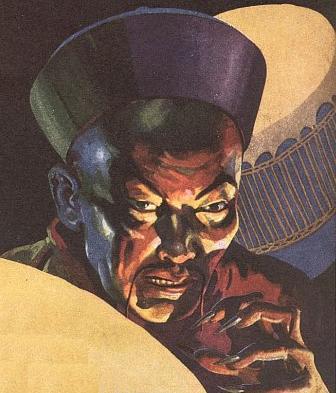

After the bloody Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which was sparked by secret societies in China whose aim was to eradicate Western and Christian influence in that country, a “Yellow Peril” panic briefly spread in the West. Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Ward) was a British journalist who haunted London’s Chinatown during that period; “The Zayat Kiss,” published in 1912, is set in that milieu. This story would be repurposed as the first three chapters of Rohmer’s popular novel The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu (1913; in the US: The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu), the first of a long series. Rohmer’s master criminal character, Fu Manchu, has since inspired depictions of sinister Asiatic science-fiction villains from Ming the Merciless to Dr. No, to Iron Man’s enemy The Mandarin.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6

I sank into an armchair in my rooms and gulped down a strong peg of brandy.

“We have been followed here,” I said.

“Why did you make no attempt to throw the pursuers off the track, to have them intercepted?”

Smith laughed.

“Useless, in the first place. Wherever we went he would find us. And of what use to arrest his creatures? We could prove nothing against them. Further, it is evident that an attempt is to be made upon my life to-night — and by the same means that proved so successful in the case of poor Sir Crichton.”

His square jaw grew truculently prominent, and he leaped stormily to his feet, shaking his clenched fists toward the window.

“The villain!” he cried. “The fiendishly clever villain! I suspected that Sir Crichton was next, and I was right. But I came too late, Petrie! That hits me hard, old man. To think that I knew and yet failed to save him!”

He resumed his seat, smoking hard.

“Fu-Manchu has made the blunder common to all men of unusual genius,” he said. “He has underrated his adversary. He has not given me credit for perceiving the meaning of the scented messages. He has thrown away one powerful weapon — to get such a message into my hands — and he thinks that, once safe within doors, I shall sleep, unsuspecting, and die as Sir Crichton died. But without the indiscretion of your charming friend I should have known what to expect when I received her ‘information,’ which, by the way, consists of a blank sheet of paper.”

“Smith,” I broke in, “who is she?”

“She is either Fu-Manchu’s daughter, his wife, or his slave. I am inclined to believe the latter, for she has no will but his will, except” — with a quizzical glance — “in a certain instance.”

“How can you jest with some awful thing — Heaven knows what — hanging over your head? What is the meaning of these perfumed envelopes? How did Sir Crichton die?”

“He died of the Zayat Kiss. Ask me what that is and I reply ‘I do not know.’ The zayats are the Burmese caravansaries, or rest houses. Along a certain route — upon which I set eyes for the first and only time upon Dr. Fu-Manchu — travelers who use them sometimes die as Sir Crichton died, with nothing to show the cause of death but a little mark upon the neck, face, or limb, which has earned in those parts the title of the ‘Zayat Kiss.’ The rest houses along that route are shunned now. I have my theory, and I hope to prove it to-night if I live. This was my principal reason for not enlightening Dr. Cleeve. Even walls have ears where Fu-Manchu is concerned. I wanted an opportunity to study the Zayat Kiss in operation, and I shall have one.”

“But the scented envelopes?”

“In the swampy forests of the district I have referred to a rare species of orchid, almost green and with a peculiar scent, is sometimes met with. I recognized the heavy perfume at once. I take it that the thing which kills the travelers is attracted by this orchid. You will notice that the perfume clings to whatever it touches. I doubt if it can be washed off in the ordinary way. After at least one unsuccessful attempt to kill Sir Crichton — you recall that he thought there was something concealed in his study on a previous occasion?—Fu-Manchu hit upon the perfumed envelopes. He may have a supply of these green orchids in his possession — possibly to feed the creature.”

“What creature? How could any creature have got into Sir Crichton’s room to-night?”

“You no doubt observed that I examined the grate of the study. I found a fair quantity of fallen soot. I at once assumed, since it appeared to be the only means of entrance, that something had been dropped down; and I took it for granted that the thing, whatever it was, must still be concealed either in the study or in the library. But when I had obtained the evidence of the groom Wills, I perceived that the cry from the lane or from the park was a signal. I noted that the movements of anyone seated at the study table were visible, in shadow, on the blind, and that the study occupied the corner of a two-storied wing and, therefore, had a short chimney. What did the signal mean? That Sir Crichton had leaped up from his chair and either had received the Zayat Kiss or had seen the thing which some one on the roof had lowered down the straight chimney. It was the signal to withdraw that deadly thing. By means of the iron stairway at the rear of Major General Platt-Houston’s I quite easily gained access to the roof above Sir Crichton’s study — and I found this.”

Out from his pocket Nayland Smith drew a tangled piece of silk, mixed up with which were a brass ring and a number of unusually large-sized split shot, nipped on in the manner usual on a fishing line.

“My theory proven,” he resumed. “Not anticipating a search on the roof, they had been careless. This was to weight the line and to prevent the creature’s clinging to the walls of the chimney. Directly it had dropped in the grate, however, by means of this ring I assume that the weighted line was withdrawn, and the thing was only held by a slender thread, which sufficed, though, to draw it back again when it had done its work. It might have got tangled, of course, but they reckoned on its making straight up the carved leg of the writing table for the prepared envelope. From there to the hand of Sir Crichton — which, from having touched the envelope, would also be scented with the perfume — was a certain move.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.