Not A Bot

By:

September 25, 2013

What is it like to be a bot?

When Alan Turing proposed his Turing Test, the object was to see if a response from a machine could be indistinguishable from a response from a human, to a typed question. You (the human interrogator) slid a typed question under two doors. Behind one, a human, behind the other, a machine. In response, two typed answers slipped out. If you, the human asker, could not tell if a reply was from a bot or not, then effectively, it was not. The Turing Test is still the gold standard for artificial intelligence, and to date, no machine has succeeded.

But what if, behind those closed doors, a human pretended to be a bot?

[Marquese Scott incorporates slo-mo, stop-motion, and other machine-inspired moves]

We’ve been imitating our machines ever since we built them to imitate us. From Taylorism to dubstep dance, from C to philosophies of mind, from streamlining to the art of the glitch; our machines, and especially our computers, have been the objects of our contemplation, amusement, oppression, admiration, and fear—not in that order, and sometimes all at once. It seems we cannot get enough of our mechanical mirror stage.

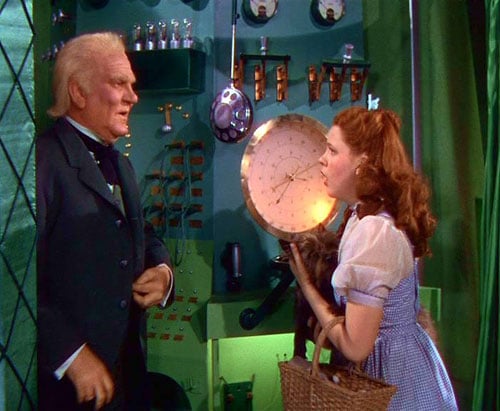

[Lucy and Harpo]

Or can we? The Twitter account @horse_ebooks was outed by Susan Orlean in The New Yorker as not a bot. Instead of being written by an algorithm, and meta-authored by a coder, it has been written, at least since 2011, by Jacob Bakkila, who describes it as a conceptual art project. Bakkila purchased it from Alexey Kuznetsov, its original Russian author, who either coded the original algorithm (so it was a bot) or just wrote it himself (so it wasn’t).

In terms of convincing everyone it was a bot, prior to the confession in legacy media-space, @horse_ebooks was not only effective, but incredibly popular. Funny, gnomic, dada, and occasionally weirdly prescient, @horse_ebooks was a scrying algorithm for digitized text strings*, the machine looking for its own ghost within, the meaninglessness at the heart of (the) matter.

Ok, so it isn’t a bot. Although it is, or was, still funny, gnomic, dada, etc., all those things for which it was celebrated, it just achieved them via imagination and not algorithm. So why the disappointment, the divestment of glamour, the widespread dismay when it was revealed that the bot had human authorship after all? Surely no one felt that dada is the path to machine sentience? Although perhaps there’s always a disappointment when the batteries run down, when the robot isn’t real, when the serial number is discovered under the feathers of the owl…

[Blade Runner: Owl Eyes]

But why not celebrate the human authors as paragons of fragmentation, wielding that razor’s edge of readable randomness that characterizes the literary gestalt of the age? Why not? We could. We should!

Although… what if it’s a sophisticated piece of viral marketing? Jacob Bakkila works as creative director of Buzzfeed. Thomas Bender has collaborated with him on a number of alternate reality games, as Synydyne, defined online as both an art collective, and an ARG company. What if the secret message is ultimately, as Ralphie discovers, “a crummy commercial?” In that case, we may rightfully feel that we have been played.

[A Christmas Story]

Our initially elusive meta-author may just turn out to be our usual suspect, the contemporary corporation, competing for our attention as it seeks to monetize every interaction, virtual and otherwise. The rage against the faux-machine is rage at marketing miasma, the fog surrouding and suffusing our every digital interaction, and, increasingly, our every interaction, period. As we consumers have grown more savvy, and more weary of being termed “consumers,” advertisements have grown more subtle, and more insidious. Instead of advertising their wares out loud, they attempt to trick us into thinking it’s our idea. The outcry at The Atlantic’s Scientology advert was that it disguised itself in the format of an article. The fatigue with “sponsored posts” infesting all of social media is that they disguise themselves as regular posts, from your friends. The outcry at a Twitter bot’s authorship is not, or not only, at the disguise of humans pretending to be a bot, but an outcry against the idea that some corporation, once again, is disguising itself behind the notion of personhood.

We want to delight in the magic in the world, the creativity and combination of humans and animals, particles and waves—yes, delight even in our machines; we want to soar with text and image to simulate meaning, then swerve to fragment and shatter it again. “Magic” here is of course a metaphor, but delightful in spite of that, or perhaps because of it. We delight in metaphor, that is magic for us. What we do not want: we do not want our metaphors monetized.

Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain? Perhaps; perhaps not. But pay very much attention to who—or what—might be paying him.

*[Interestingly, this is not so different from how Watson, IBM’s Jeopardy-winning array, operates and “learns:” Watson scans our digitized texts from literature to operating manuals for anything that might look like an answer to be formed into a question.]