The Zayat Kiss (2)

By:

September 18, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the second installment of our serialization of Sax Rohmer’s story “The Zayat Kiss.” New installments will appear each Wednesday for six weeks.

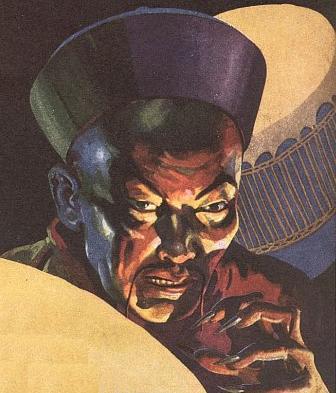

After the bloody Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which was sparked by secret societies in China whose aim was to eradicate Western and Christian influence in that country, a “Yellow Peril” panic briefly spread in the West. Sax Rohmer (Arthur Henry Ward) was a British journalist who haunted London’s Chinatown during that period; “The Zayat Kiss,” published in 1912, is set in that milieu. This story would be repurposed as the first three chapters of Rohmer’s popular novel The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu (1913; in the US: The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu), the first of a long series. Rohmer’s master criminal character, Fu Manchu, has since inspired depictions of sinister Asiatic science-fiction villains from Ming the Merciless to Dr. No, to Iron Man’s enemy The Mandarin.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

“What’s this?” muttered my friend hoarsely.

Constables were moving on a little crowd of carious idlers who pressed about the steps of Sir Crichton Davy’s house and sought to peer in at the open door. Without waiting for the cab to draw up to the curb, Nayland Smith recklessly leaped out, and I followed closely at his heels.

“What has happened?” he demanded breathlessly of a constable.

The latter glanced at him doubtfully, but something in his voice and bearing commanded respect.

“Sir Crichton Davey has been killed, sir.”

Smith lurched back as though he had received a physical blow, and clutched my shoulder convulsively. Beneath the heavy tan his face had blanched, and his eyes were set in a stare of horror.

“My God!” he whispered. “Just too late!”

With clenched fists he turned and, pressing through the group of loungers, bounded up the steps. In the hall a man who unmistakably was a Scotland Yard official stood talking to a footman. Other members of the household were moving about, more or less aimlessly, and the chilly hand of, King Fear had touched one and all, for, as they came and went, they glanced ever over their shoulders, as if each shadow cloaked a menace, and listened, as it seemed, for some sound which they dreaded to hear.

Smith strode up to the detective and showed him a card, upon glancing at which the Scotland Yard man said something in a low voice, and, nodding, touched his hat to Smith in a respectful manner.

A few brief questions and answers, and, in gloomy silence, we followed the detective up the heavily carpeted stair, along a corridor lined with pictures and busts, and into a large library. A group of people were in this room, and one, in whom I recognized Chalmers Cleeve of Harley Street, was bending over a motionless form stretched upon a couch. Another door communicated with a small study, and through the opening I could see a man on all fours examining the carpet. The uncomfortable sense of hush, the group about the physician, the bizarre figure crawling, beetlelike, across the inner room, and the grim hub, around which all this ominous activity turned, made up a scene that etched itself indelibly on my mind.

As we entered. Dr. Cleeve straightened himself, frowning thoughtfully.

“Frankly, I do not care to venture any opinion at present regarding the immediate cause of death,” he said. “Sir Crichton was addicted to cocaine, but there are indications which are not in accordance with cocaine poisoning. I fear that only a post-mortem can establish the facts — if,” he added, “we ever arrive at them. A most mysterious case!”

Smith stepping forward and engaging the famous pathologist in conversation, I seized the opportunity to examine Sir Crichton’s body.

The dead man was in evening dress, but wore an old smoking jacket. He had been of spare but hardy build, with thin, aquiline features, which now were oddly puffy, as were his clenched hands. I pushed back his sleeve and saw the marks of the hypodermic syringe upon his left arm. Quite mechanically I turned my attention to the right arm. It was unscarred, but on the back of the hand was a faint red mark, not unlike the imprint of painted lips. I examined it closely, and even tried to rub it off, but it evidently was caused by some morbid process of local inflammation if it were not a birthmark.

Turning to a pale young man whom I had understood to be Sir Crichton’s private secretary, I drew his attention to this mark and inquired if it were constitutional.

“It is not, sir,” answered Dr. Cleeve, overhearing my question. “I have already made that inquiry. Does it suggest anything to your mind? I must confess that it afforded me no assistance.”

“Nothing,” I replied. “It is most curious.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Burboyne,” said Smith, now turning to the secretary, “but Inspector Weymouth will tell you that I act with authority. I understand that Sir Crichton was — seized with illness in his study?”

“Yes, at half-past ten. I was working here in the library and he inside, as was our custom.”

“The communicating door was kept closed?”

“Yes, always. It was open for a minute or less about ten-twenty-five, when a message came for Sir Crichton. I took it in to him, and he then seemed in his usual health.”

“What was the message?”

“I could not say. It was brought by a district messenger, and he placed it beside him on the table. It is there now, no doubt.”

“And at half-past ten?”

“Sir Crichton suddenly burst open the door and threw himself, with a scream, into the library. I ran to him, but he waved me back. His eyes were glaring horribly. I had just reached his side when he fell, writhing, upon the floor. He seemed past speech, but as I raised him and laid him upon the couch he gasped something that sounded like ‘The red hand!’ Before I could get to the bell or telephone he was dead!”

Mr. Burboyne’s voice shook as he spoke the words, and Smith seemed to find this evidence confusing.

“You do not think he referred to the mark on his hand?”

“I think not. From the direction of his last glance I feel sure he referred to something in the study.”

“What did you do?”

“Having summoned the servants, I ran into the study. But there was nothing unusual to be seen. The windows were closed and fastened. He worked with closed windows in the hottest weather. There is no other door, for the study occupies the end of a narrow wing, so that no one could possibly have gained access to it while I was in the library unseen by me. Had some one concealed himself in the study earlier in the evening — and I am convinced that it offers no hiding place — he could only have come out again by passing through here.”

Nayland Smith tugged at the lobe of his left ear, as was his habit when meditating.

“You had been at work here in this way for some time?”

“Yes. Sir Crichton was preparing an important book.”

“Had anything unusual occurred prior to this evening?”

“Yes,” said Mr. Burboyne with evident perplexity, “though I attached no importance to it at the time. Three nights ago Sir Crichton came out to me and appeared very nervous; but at times his nerves — you know? Well, on this occasion he asked me to search the study. He had an idea that something was concealed there.”

“Something or some one?”

“‘Something’ was the word he used. I searched, but fruitlessly, and he seemed quite satisfied and returned to his work.”

“Thank you, Mr. Burboyne. My friend and I would like a few minutes’ private investigation in the study.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.