Theodore Savage (24)

By:

August 19, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-fourth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

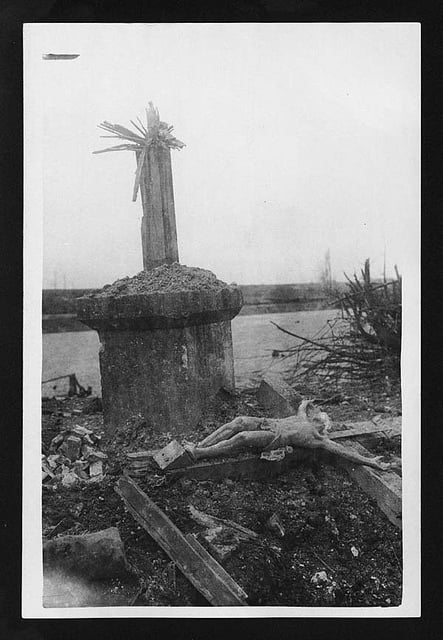

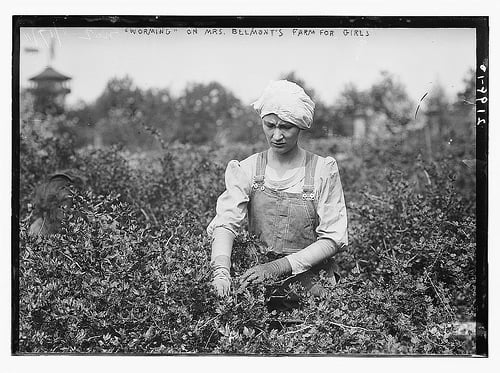

Outside the little fortress with its noisome huddle of sheds and shelters lay a belt of ploughed land, of patches scraped and sown, where the women worked by the side of their men and worked alone when their men were gone hunting or fishing. One or two members of the tribe who were countrymen born were its saviours in its first years of leanness, imparting their knowledge of soil and seed to their unskilled comrades bred in towns; and, by slow degrees, as the lesson was learned, the belt of tilled ground grew wider and more fertile, the little community more prosperous.

As families grew and the tribe settled down the makeshift shelters of wood and moss were succeeded by stronger and better built cabins; by the time that her second child was born Ada was established in a weatherproof hut — a mud-walled building, roofed with dried grass and with a floor of earth beaten hard. In its early years it possessed a glazed window, a pane which Theodore had found whole in a crumbling house and set immovably in an aperture cut in his wall. But, as years went on, unbroken glass was hard to come by; and there came a day when the window-aperture, no longer glazed, was plastered up to keep out the weather.

Long before he set about the building of his cabin Theodore had brought a strip of ground under cultivation, sown a patch of potatoes and straggling beans which, in time, expanded to a field. His life, henceforth, was largely the anxious life of the seasons; the sowing and tending and reaping of his crop, the struggle with the soil and the barrenness thereof, the ceaseless war against vermin…. He ended rich, as the men of his time counted riches; the possessor of goats, the owner of land which other men envied him, the father of sons who could till it. The new world gave him what it had to give; and gradually, with the passing of years, the hope of life civilized died in him and he ceased to strain his eyes at the distance.

It was slowly, very slowly, that hope died in him; but there came a day when, searching the skyline, as his habit was, it dawned on his mind that he sought automatically; it was habit only that made him lift his eyes to the horizon. He expected nothing when he shaded his eyes and looked this way and that; his belief in a world that was lettered and civilized had vanished. If that world yet existed, remote and apart, of a surety it was not for him — who perhaps was no longer capable of existence lettered and civilized. And if he himself could be broken to its decencies, what place had his children, his young barbarians, in an ordered atmosphere like that of his impossible youth? They belonged to their world, to its squalor, its dirt, its rude ignorance… as, it might be, he also belonged.

At the thought, he knelt and stared into the water, taking stock of the image it reflected and coming face to face with himself. His body and habits had adapted themselves to their surroundings, his mind to the outlook of his world — to his daily, yearly struggle with the soil and vermin and his fellows. His relations with his fellows — with women — with himself — were not those of humanity civilized; it was nothing to him to go foul and unwashed or to clench his fist against his wife. Could he live the life he had been born and bred to, of cleanliness, self-control and courtesy? Or had he been stripped of the decencies which go to make civilized man?… He covered his face with his broken-nailed fingers and strove with God and his own soul that he might not fall utterly to ruin with his world, that some remnant might remain of his heritage.

From the day when he saw himself for what he was and resigned all hope of the world of his youth, it seemed to him that he lived two divergent lives. One absorbed, perforce, in his digging and snaring, in the daily struggle, for the daily wants of his household; the other — in his hours of summer rest, in the long dark winter evenings — an inward life of brooding that concerned itself only with the past.

His memories became to him a species of cult, a secret ceremonial and a rite; that which had been (so he fancied) was not altogether waste, not altogether dead, so long as one man thought of it with reverence. When the mood took him he would sit for long hours with his chin on his hand, staring at the fire while the children wondered at his silence — and Ada, wearied of talking to deaf ears, flung off to gossip with the neighbours.

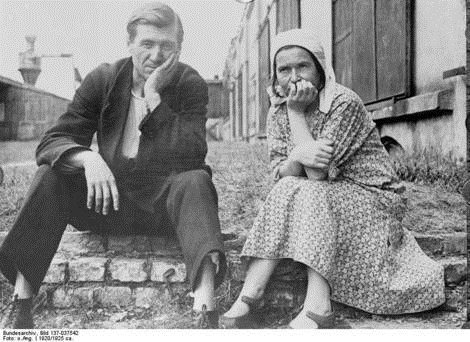

She, before she was thirty, was a haggard slattern of a woman; pitiable by reason of her discontent, and looking far older than her years. Childbearing aged her and the field-work she hated — the bent-backed drudgery she tried in vain to shirk and to which she brought no shred of understanding; even more she was aged by the weary desire that sulked in the corners of her mouth. Before she lost her comeliness she had more than once sought distraction from her dullness in clumsy flirtation; which perhaps was no more than silly ogling and nudging and perhaps led to actual unfaithfulness. Theodore — not greatly interested in his wife’s doings — ignored the danger to his household peace until it was forcibly thrust upon his notice by a jealous spitfire who cursed Ada for running after other women’s husbands, and proceeded to tear out her hair. Ada’s snuffling protestations when the spitfire was pulled off did not savour of injured innocence; he judged her guilty, at least in thought, cuffed her soundly and from that time kept his eye on her. He was not (as she liked to think) jealous — salving her bruises with the comforting balm that two males were disputing the possession of her body; what stirred him to wrath fundamentally was his outraged sense of property in Ada, his woman, and the possibility that her lightness might entail on him the labour of supporting another man’s child. The intrigue — if intrigue it were — ended on the day of the cuffing and hair-pulling; her Lothario, awed by his spitfire or unwilling to tackle an outraged husband, avoided her company from that day forth and Ada sank back to domesticity.

She, too, in the end accepted the loss of the world that had made her what she was, ceased to search the horizon and strain her eyes for the deliverer; whereupon — having nothing to aim at or hope for — she lapsed into slovenly neglect of her home, alternating hours of clack and gossip with fits of sullen complaining at the daily misery of existence.

Had destiny realized the dreams of her youth and set her to live out her married life in a shoddy little villa with bamboo furniture, she might have made a tolerable mother; she would at least have taken pride in the looks of her children, have dressed them with interest, as she dressed herself, and tied up their hair with satin bows. Being what she was, she could take no pride in ragamuffins who ran half the year naked; she could see no beauty, even, in straight agile limbs which were meant to be encased in reach-me-down suits or cheap costumes of cotton velveteen. Thus her naked little ragamuffins — those of them that lived — were apt to be dirtier, less cared-for, than the run of the dirty village youngsters. Theodore, in whom the instinct of fatherhood was strong, was sometimes roused to wrath by her stupid mishandling of her children; but, on the whole he was patient with her — knowing it useless to be otherwise. He beat her as seldom as possible and she was looked on by her neighbours as a woman kindly handled and unduly blessed in her husband. To the end she remained what she had always been; essentially a parasite, a minor product of civilization, machine-bred and crowd-developed — bewildered by a life not lived in crowds and not subject to the laws of the Machine. To the end all nature was alien and hateful to her — raw life that she turned from with disgust…. In her last illness her mind, when it wandered, strayed back into the world where she belonged; Theodore, an hour before she died, heard her muttering of “last Bank ’Oliday.”

She died at the end of a long hard winter during which she had failed and complained unceasingly, sat huddled to the fire and grown weaker; creeping, at last, to her straw in the corner and forgetting, in delirium, the meaningless life she had shared with her husband and children. Death smoothed out the lines in her sullen face; it was peaceful, almost comely, when Theodore looked his last on it — and wondered, oddly, if among the “many mansions,” were some Cockney paradise of noise and jostle where his wife had found her heart’s desire?

Of the four or five children she had brought into the world but two were living on the day of her death, her eldest-born and a youngster at the crawling stage; but the care of even two children was a burdensome matter for a man unaided, and it was esteemed natural and no insult to the dead, that Theodore should take another wife as speedily as might be — in the course not of months but of weeks. He found a woman to suit his needs without going further than his own tribe; a woman left widowed a year or two before, who was glad enough to accept the offer of a better living than she could hope to make by her own scratching of a rod or two of earth and the uncertain charity of neighbours. The proposal of marriage, made in stolid fashion, was accepted as a matter of course… and, that night, Theodore stared through the fire into a room in Westminster where a girl in a yellow dress made music… and a young man listened from the corner of a sofa with a cigarette, unlit, between his fingers. He was dreaming at a table — with silver and branching yellow roses — when his son nudged him that supper was ready, and he dipped his hand into a greasy bowl for the meat.

The wedding followed swiftly on the heels of betrothal, and was celebrated in the manner already compulsory and established; by a public promise made solemnly before the headman, by a clasping of hands and a ceremony of religious blessing. This last was moulded, like all tribal ceremonies, on remembered formulae and ritual; and the tradition that a wedding should be accompanied by much eating and general merrymaking was also faithfully observed.

The new wife, if not over comely or intelligent, was a sturdy young woman who had been broken to the duties required of her, and Theodore’s home, under its second mistress, was better tended and more comfortable than in the days of her sluttish predecessor. He had married her simply as a matter of business, that she might help in his field-work, cook his food, look after his children and satisfy his animal desire; and on the whole he had no reason to complain of the bargain he had made. She was a younger woman than Ada by some years — had been only a slip of a girl at the time of the Ruin — and, because of her youth, had adapted herself more readily than most of her elders to a world in the making and untraditioned methods of living. Her husband found life easier for the help of a pair of sturdy arms and pleasanter for lack of Ada’s grumbling…. She brought more than herself to Theodore’s household — a child by her first husband; and, as time went on, she bore him other children of his own.

As the years went by and his children grew to manhood in the world primitive which was the only world they knew, the life of Theodore Savage became definitely twofold; a life of the body in the present and a life of the mind in the past. There was his outward, rustic and daily self, the labourer, hunter and fisherman, who begat sons and daughters, who trudged home at nightfall to eat and sleep heavily, who occasionally cudgelled his wife: a sweating, muscular animal man whose existence was bounded by his bodily needs and the bodily needs of his children; who fondled his children and cuffed them by turns, as the beast cuffs and fondles its offspring. Whose world was the world of a food-patch enclosed in a valley, of a river where he fished, a wood where he snared and a hut that received him at evening…. In time it was of these things, and these things only, that he spoke to his kin and his neighbours; the weather, the luck of his hunting or fishing, the loves, births and deaths of his fellows. With the rise and growth of a generation that knew only the world primitive, the little community lived more in the present and less in the past; mention of the world that had vanished was even less frequent and even more furtive than before.

And even if that had not been the case, there was no man in the tribe, save Theodore, whose mind was the mind of a student; thus his other life, his life of the past, was lived to himself alone. It was a vivid memory-life in which he delved, turning over its vanished treasures — the intangible treasures of dead beauty, dead literature, learning and art; a life that at times receded to a dream of the impossible and at others was so real and overwhelming in its nearness that the everyday sweating and toiling and lusting grew vague and misty — was a veil drawn over reality.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”