Ross MacDonald: 3rd Man

By:

August 10, 2013

If one seeks masters of the American hard-boiled mystery, one rarely looks farther than the two men at the form’s beginning, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, who — to paraphrase T.S. Eliot — divide the world between them and leave no third. Hammett is the genre’s father, whose novels all swerve in different stylistic directions, each offering a new model of detective, and a new vision of the fluid dangers of American society. Chandler is more public-school literary, refining over seven novels the detective as “shop-soiled Galahad,” steeped in but standing up to the sins of a vain, sun-washed world.

That’s one way of looking at it, but there are limits to the work of both, given the time and each man’s temper: Hammett stays at arms-length, Chandler is sentimental and a prude. The real issue is that both remain 19th century men in their hearts, tracking its slow-motion death into the first half of the 20th. It’s a third writer who lodges the American noir squarely in the post-war 20th century, in a modern landscape still recognizable, and raw.

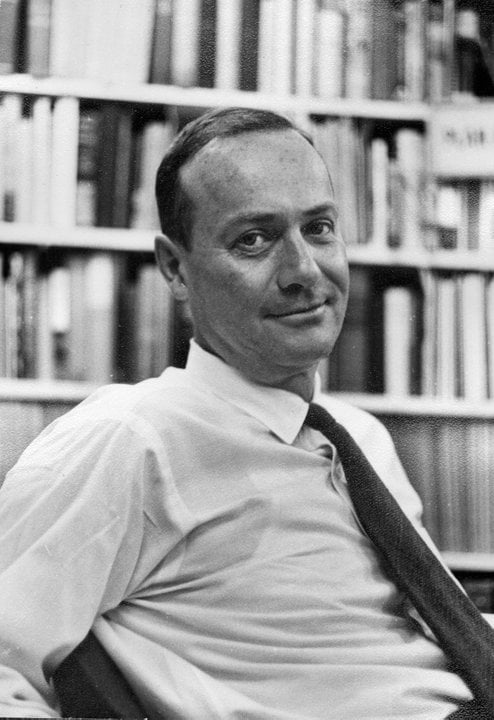

Kenneth Millar was born in 1915, in Los Gatos, California, but raised in Canada. After the war he pursued a teaching career, but started writing stories for the pulp magazines and published his first novel — The Dark Tunnel, under the name John Macdonald — while working toward his Ph.D. The pseudonym came so not to compete with his wife, Margaret Millar, who’d begun to establish herself as a mystery novelist (Beast in View is probably her best-known book, and well worth searching out). Three more John Macdonald novels followed, none especially successful, but the writing of them wrenched him out of academia. In 1949 The Moving Target appeared, the first Ross Macdonald novel, and the first to feature the detective Lew Archer.

Seventeen more Archer books would follow. They’re all worth reading, but Macdonald really hits his stride around 1956 with The Barbarous Coast. From then on the books get better and better, and Macdonald’s great theme appears, of the inescapable shadow of the past, especially the sins by which the present day’s wealth has been achieved. It’s an especially American theme, and twinned in his depiction of 1950s-1970s California to the thoughtless sacrifice of the natural world to commerce. His next-to-last novel, Sleeping Beauty, begins at a beach despoiled by an oil spill, and throughout the twisting case the spill echoes like the inescapable consequence of human greed.

Simply in terms of the hard-boiled mystery, the books are audaciously accomplished. Macdonald’s intricate plots are like Sophocles by way of a boa constrictor. His subtle reconfiguration of the detective character tips the Archer books toward social portrait and social critique without the burden of any particular axe being ground. Archer isn’t an avatar of tough virtue for the reader’s vicarious thrill. He may be a catalyst within the stories, but most profoundly and more simply he’s a witness. If Chandler’s novels are about Marlowe, then Macdonald’s — despite Archer’s fuller realization — are about California. But most remarkable is the compassion with which these unsparing tales are unwound. The compassion is never soft, but feels truthful without being cruel.

His strongest books — Black Money, The Chill, The Underground Man, The Instant Enemy, Sleeping Beauty — stand with anything in the field. His final novel, The Blue Hammer, is all the more impressive for being gentler at the edge. The next year early-onset Alzheimers would claim Millar’s writing at the age of 62, and his life 7 years after that.