Theodore Savage (22)

By:

August 5, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-second installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

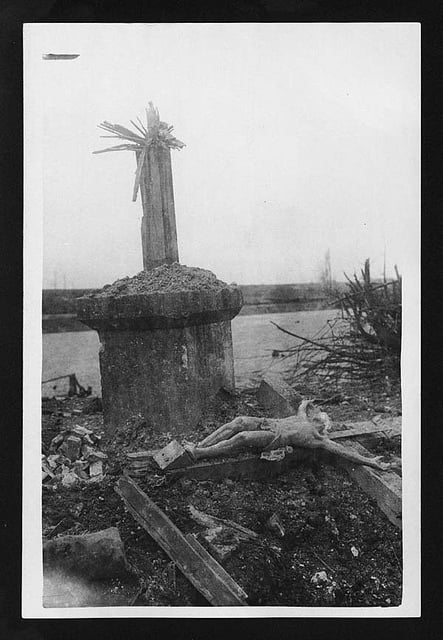

The goal of his first journey was the town lying lower down the river, the forbidden city which had once bred pestilence and flies. He approached it deviously, keeping to the hills and avoiding districts he knew to be inhabited; hoping against hope, that, in spite of report, he might find some rebuilding of a civic existence and human life as he had known it…. What he found when he came down from the foothills and trudged through its outskirts was the customary silent desolation; a desolation flooded and smelling of foul water — untenanted streets that were channels and backwaters, and others where the slime of years lay thick and scum bred rank vegetation. Silent streets and empty houses had long been familiar to him, but until that day he had not known how swiftly nature, left to herself, could take hold of them. The river and the life that sprang from it was overwhelming what man had deserted. Three winters of neglect in a low-lying, well-watered country had wrought havoc with the work of the farmer and the engineer; streams which had been channelled and guided for centuries had already burst their way back to freedom. With every flooded winter more banks were undermined, more channels silted up and shifted; and that which had been plough-land, copse or water-meadow was relapsing into bog undrained. The valley above and below the town was a green swamp studded with reedy little pools; a refuge for the water-bird where a man would set foot at his peril. Buildings here and there stood rotting, forlorn and inaccessible — barns, sheds and farm-houses, their walls leaning drunkenly as foundations shifted in the mud; and in the town itself, as surely, if more slowly, the waters were taking possession…. Towns had vanished, he knew — vanished so completely that their very sites had been matter of dispute to antiquarians — but never till to-day had he visualized the process; the rising of layer on layer of mud, the sapping of foundations by water. The forces that made ruin and the forces that buried it; flood and frost and the persistent thrust of vegetation. As the water-logged ground slid beneath them, rows of jerry-built houses were sagging and cracking to their fall; here and there one had crumbled and lay in a rubble heap, the water curdling at its base…. How many life-times, he wondered, till the river had the best of it and the houses where men had gone out and in were one and all of them a rubble heap — under water and mud and rank greenery? He saw them, decades or centuries ahead, as a waste, a stretch of bogland where the river idled; bogland, now flooded, now drying and cracked in the sun; and with broken green islets still thrusting through the swamp — broken green islets of moss-covered rock that underneath was brick and mortar. In time it might be — with more decades or centuries — the islets also would sink lower in the swamp, disappear….

The process, unhindered, was certain as sunrise; the important little streets that humanity had built for its vanished needs and its vanished business would be absorbed into an indifferent wilderness, in all things sufficient to itself. The rigid important little streets had been no more than an episode in the ceaseless life of the wilderness; an episode ending in failure, to be decently buried and forgotten.

He plodded aimlessly through street after street that was fordable till the shell of a “County Infirmary” mocked at Ada’s hopes and recalled the first purpose of his journey; a gaunt sodden building, the name yet visible on walls that sweated fungi and mould. Then, that he might leave nothing undone in the way of help and search, he trudged and waded to the lower outskirts of the town; where the roads lost themselves in grass and flooded water, and there stretched to the limit of his eyesight a dull winter landscape without sign of living care or habitation. In the end — having strained his eyes after that which was not — he turned to slink back to his own place; skirting alien territory where the sight of a stranger might mean an alarm and a manhunt, and sheltering at night where his fire might be hidden from the watcher.

“You ’aven’t found nothin’?” Ada whimpered, when he had told his necessary lies to the curious and they were out of earshot in their hut. Her eyes had grown piteous when he stumbled in alone; she had dreamt in his absence of sudden and miraculous deliverance — following him in fancy through streets with tramlines, where dwelt women who wore corsets — also doctors. Who, perhaps, when they knew the greatness of her need, would send a motor-ambulance — to fetch her to a bed with sheets on it.

“Nothing,” he told her almost roughly, afraid to show pity. “No doctors, no houses fit to live in. Wherever I’ve been and as far as I could see — it’s like this.”

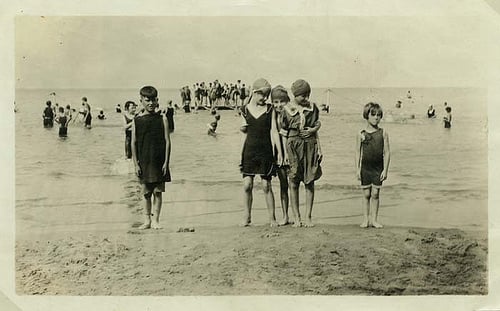

It was in the third spring after the Ruin of Man that Ada’s time was accomplished and she bore a son to her husband; on a day in late April or early May there was going and coming round the shelter that was Theodore’s home. The elder women of the tribe, by right of their experience, took possession, and from early morning till long after nightfall they busied themselves with the torment and mystery of birth; and with the aid of nothing but their rough and unskilled kindliness Ada suffered and brought forth a squalling red mannikin — the heir of the ages and their outcast. The child lived and, despite its mother’s fecklessness, was lusty; as a boy, ran shoeless, and, in summer, naked as Adam; and grew to his primitive manhood without letters, knowing of the world that was past and gone only legends derived from his elders.

His coming, to Theodore, meant more than paternity; the birth of his son made him one with the life of the tribe. By the child’s wants and helplessness — still more when other children followed — his father was tied to an existence which offered the necessary measure of security; to the stretch of land where he had the right to hunt unmolested, the patch he had the right to sow and reap, and the company of those who would aid him in protecting his children. He had given his hostages to fortune and the limits set to his secret expeditions in search of a lost world were the limits set by the needs of those dependent on him, by his fear of leaving them too long unprotected, unprovided for.

He learned much from his firstborn and the brothers and sisters who followed him; not only the intimate lore of his fatherhood, but the lore and outlook of man bred uncivilized, and the traditions, in making, of a world to come — which in all things would resemble the old traditions handed down by a world that had died. His children lived naturally the life that had been forced upon their father and inherited ignorance as a birthright; growing up — such as lived through the perils of childhood — without knowledge of the past and untempted by the sin of the intellect. The oath which Theodore, like every new-made father, was called on to swear in the name of the child he had given to the tribe, had a meaning to those who had lived through Disaster and witnessed the Ruin of Man; to the next generation the vow was a formula only, a renunciation of that they had never possessed. They could not, if they would, instruct their children in the secrets of God, the forbidden lore of the intellect.

By the time his first son was of an age to think and question, Theodore understood more than the growth and workings of a child-mind — much that had hitherto seemed dark and fantastic in the origins of a world that had ended with the Ruin of Man. It was the workings of a child-mind that made oddly clear to him the significance of primitive religious doctrine and beliefs handed down through the ages — the once meaningless doctrine of the Fall of Man and the belief in a vanished Golden Age. These the boy, unprompted, evolved from his own knowledge and the talk of his elders, accepting them spontaneously and naturally.

In Theodore’s childhood the Golden Age had been a myth and pleasant fancy of the ancients, and the Fall of Man as distant as the Book of Genesis and unreal as the tale of Puss-in-Boots; to his children, one and all, the legends of his infancy were close and undoubted realities. The Golden Age was a wondrous condition of yesterday; the Fall — the Ruin — its catastrophic overthrow, an experience their father had survived. The fields and hillsides where they worked, played and wandered were still littered with strange relics of the Golden Age — the vanished, fruitful, incomprehensible world whence their parents had been cast into the outer darkness of everyday hardship as a penalty for the sin of mankind. The sin unforgivable of grasping at the knowledge which had made them like unto gods; a mad ambition which not only they but their children’s children must atone for in the sweat of their brow…. More than once Theodore suspected in the secret recesses of his youngsters’ minds a natural and wondering contempt for the men of the last generation; the fools and blind who had overreached themselves and forfeited the splendour of the Golden Age by their blundering greed and unwisdom. So history was writing itself in their minds; making of a race that had acquiesced in science and drifted to destruction a legendary people whose sin was deliberate — a people whose encroachments had angered a self-important Deity and brought down his wrath upon their heads. It was a history inseparable from religious belief; its opening chapters identical in all essentials with the legendary history of an epoch that had ceased to exist.

Once his eight-year boy, planted sturdily before him, demanded a plain explanation of the folly of his father’s contemporaries.

“Why,” he asked frowning, “did the people want to find out God’s secrets?”

Theodore thought of Ada and the countless millions like her, leaned his chin on his hand and smiled grimly.

“Some of us didn’t,” he answered. “Some of us — many of us — had no interest in the secrets of God. We made use of them when others found them out, but we, ourselves, were quite content to be ignorant. Ignorant in all things.”

“I know,” the child assented, puzzled by his father’s smile. “The good ones didn’t want to — the good ones like you and Mummy. But the others — all the wicked ones — why did they? It was stupid of them.”

“They wanted to find out,” said Theodore, “and there have always been people like that. From the beginning, the very beginning of things — ever since there were men on the earth. The desire to know burned them like a fire. There is an old story of a woman who brought great trouble into the world because she wanted to know. She was given a box and told never to open it; but she disobeyed because she was filled with a great curiosity to know what had been put inside it. Her longing tormented her night and day and she could think of nothing else; till at last she opened the box and horrible creatures flew out.”

The boy, interested, demanded more of Pandora and the horrible creatures. “Is it a true story?” he asked when his father had

given such further details as he managed to remember and invent.

“Yes,” Theodore told him, “I believe it is a true story. It was so long ago that we cannot tell exactly how it happened: I may not have told it you quite rightly, but on the whole it is a true story…. And the wicked people — our wicked people who brought ruin on the world — were much like Pandora and her box. It was the same thing over again; they wanted to know so strongly that they forgot everything else; they had only the longing to find out and it seemed as if nothing else mattered.”

“Weren’t they afraid?” the boy asked doubtfully, still puzzled by his father’s odd smile. “Afraid of what would happen to them?”

“No,” Theodore answered. “Until it was too late and they saw what they had done, I don’t think many were afraid. Here and there, before the end, some began to be frightened, but most of them didn’t see where they were going.”

“But they must have known,” his son insisted, frowning. “God told them He would punish them if they tried to learn His secrets.”

“Yes,” Theodore assented — with the orthodox truth, more deceptive than a lie, that meant one thing to him and another to the world barbarian. “Yes, God told them so; but though He said it very plainly not many of them understood….” They were talking, he knew, across more than the gulf between the mind of a child and a man; between them lay the centuries, the barrier of many generations. To his son, now and always, dead and gone chemists and mathematicians must appear in the likeness of present evildoers — raiders of the territory and robbers of the property of God; to his son, now and always, inventors and spectacled professors in mortar-boards would be greedy, foolish chieftains who planned war against Heaven as a tribe plans assault upon its rivals. These were and must always be his “wicked,” his destroyers of the Golden Age; his life and outlook being what it was, how should he picture the war against Heaven as pure-hearted, instinctive and unconscious?

“Why not?” the child persisted, repeating the question when his father stroked his head absently.

“Because… they did not know themselves. If they had known themselves and their own passions they would have seen why knowledge was forbidden.”

“Yes,” said the child vaguely — and passed to the matter that interested him.

“Why didn’t the others make them understand? You and the other good ones?”

“Because,” said Theodore, “we ourselves didn’t understand. That was the blunder — the sin — of the rest of us. We didn’t seek after knowledge, but we took the fruits of other men’s knowledge and ate.”

(Unconsciously he made use of the familiar hereditary simile.)

“I’d have killed them,” his son declared firmly. “Everyone. I’d have told them to stop, and then, if they wouldn’t, I’d have killed them. Thrown them in the river — or hammered them with stones till they died. That’s what I’d have done.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.