Theodore Savage (18)

By:

July 8, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eighteenth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

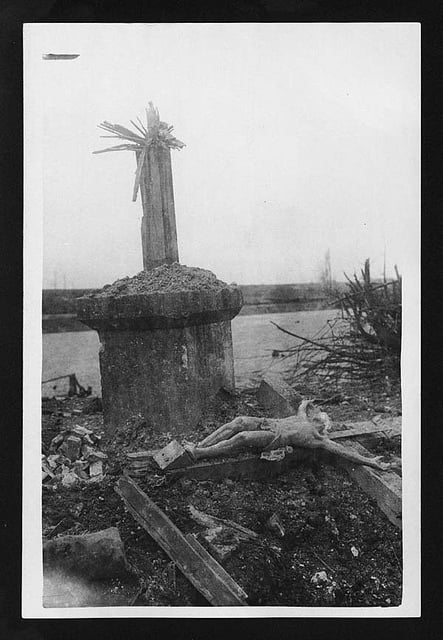

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

“Tell me,” at last came the order, “what you were doing here. Tell me everything” — and he lifted a dirty lean finger like a threat — “what you were doing on our land, where you came from, what you want?… and speak the truth or it will be the worse for you.”

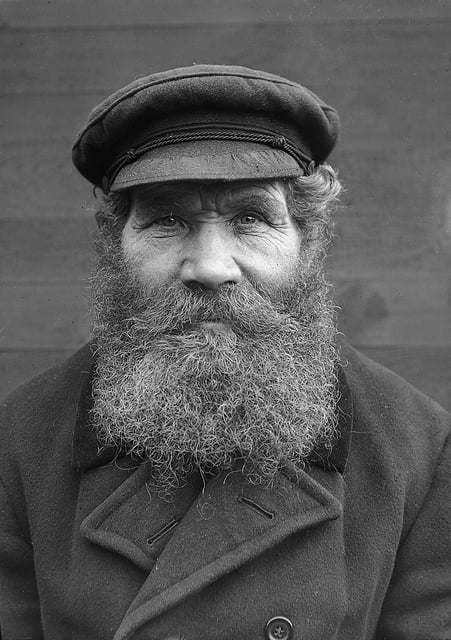

Theodore told him; while the steel-blue eyes searched his face as well as they might in the semi-darkness and the half-seen crowd stood mute. He told of his life as it had been lived with Ada; of their complete separation from their fellows for the space of nearly two years; of the coming of the child and the consequent need of help for his wife — conscious, all the time, not only of the questioning, unshrinking eyes of his judge but of the other eyes that watched him suspiciously from the corners and shadows of the room. Two or three times he faltered in his telling, oppressed by the long, steady silence; for throughout there was no comment, no word of interest or encouragement — only once, when he paused in the hope of encouragement, the old man ordered “Go on!”… He went on, striving to steady his voice and pleading against he knew not what of hostility, suspicion and fear.

“… And so,” he ended uncertainly, “they found me. I wasn’t doing any harm…. I suppose they saw my fire?…”

From someone in the darkness behind him came a grunt that might indicate assent — then, again, there was silence that lasted…. The dumb, heavy threat of it was suddenly intolerable and Theodore broke it with vehemence.

“For God’s sake tell me what you’re going to do! It’s not much I ask and it’s not for myself I ask it. If you can’t help me yourselves there must be other people who can — tell me where I am and where I ought to go. My wife — she must have help.”

There was no actual response to his outburst, but some of the half-seen figures stirred and he heard a muttering in the shadow that he took for the voices of women.

“Tell me where I am,” he repeated, “and where I can go for help.”

It was the first question only that was answered.

“You are on our land.”

“Your land — but where is it? In what part of England?”

“I don’t know,” said the old man and shrugged his lean shoulders. “But you haven’t any right on it. It’s ours.”

He pushed back his chair and stood up to his full, tall height; then, raising his hand, addressed the assembly of his followers.

“You have all of you heard what he said and know what he wants. Now let me hear what you think. Say it out loud and not in each other’s ears.”

He dropped his arm and stood waiting a reply — and after a moment one came from the back of the room.

“It’s winter,” said a man’s voice, half-sulky, half-defiant, “and we’ve hardly enough left for ourselves. We don’t want any more mouths here — we’ve more than we can fill as it is.” A murmur of agreement encouraged him and he went on — louder and pushing through the crowd as he spoke. “We fend for our own and he must fend for his. He ought to think himself lucky if we let him go after we’ve taken him on our land. What business had he there?”

This time the murmur of agreement was stronger and a second voice called over it:

“If we catch him here again he won’t get off so easily!”

The assent that followed was more than assent; applause that swelled and grew almost clamorous. The old man stilled it with a lifting of his knotted hand.

“Then you won’t have him here? You don’t want him?”

The “No” in answer was vigorous; refusal, it seemed, was unanimous. Theodore tried to speak, to explain that all he asked… but again the knotted hand was lifted.

“And are you — for letting him go?”

The words dropped out slowly and were followed by a hush — significant as the question itself…. This much was clear to the listener: that behind them lay a fear and a threat. The nature of the threat could be guessed at — since they would not keep him and dared not let him go; but where and what was the motive for the fear that had prompted the slow, sly question and the uneasy silence that followed it?… He heard his own heart-beats in the long uneasy silence — while he sought in vain for the reason of their dread of one man and tried in vain to find words. It seemed minutes — long minutes — and not seconds till a voice made answer from the shadows:

“Not if it isn’t safe.”

And at the words, as a signal, came voices from this side and that — speech hurried, excited and tumultuous. It wasn’t safe — what did they know of him and how could they prove his story true? He might be a spy — now he knew where to find them, knew they had food, he might come back and bring others with him! When he tried to speak the voices grew louder, overshouted him — and one man at his side, gesticulating wildly, cried out that they would be mad to let him go, since they could not tell how much he knew. The phrase was taken up, as it seemed in panic — by man after man and woman after woman — they could not tell how much he knew! They pressed nearer as they shouted, their faces closing in on him — spitting, working mouths and angry eyes. They were handling him almost; and when once they handled him — he knew it — the end would be sure and swift. He dared not move, lest fingers went up to his throat. He dared not even cry out.

It was the old man who saved him with another call for silence. Not out of mercy — there was small mercy in the lined, dirty face — but because, it seemed, there was yet another point to be considered.

“If they came again” — he jerked his head towards the open — “we should be a man the stronger. Now they are stronger than we are — by nearly a dozen….”

Apparently the argument had weight, for its hearers stood uncertain and arrested — and instinct bade Theodore seize on the moment they had given him…. What he said in the beginning he could not remember — how he caught their attention and held it — but when cooler consciousness returned to him they were listening while he bargained for his life…. He bargained and haggled for the right to live — offering goods and sweat and muscle in exchange for a place on the earth. He was strong and would work for them; he could hunt and fish and dig; he would earn by his labour every mouthful that fell to him, every mouthful that fell to his wife… More, he had food of his own laid away for the winter months — dried fish and nuts and the store of fruit he had salved and hoarded from the autumn. These all could be fetched and shared if need be…. He bribed them while they haggled with their eyes. Let them come with him — any of them — and prove what he said; he had more than enough — let them come with him…. When he stopped, exhausted and sobbing for breath, the extreme of the danger had passed.

“If he has food,” someone grunted — and Theodore, turning to the unseen speaker, cried out — “I swear I have! I swear it!”

He hoped he had won; and then knew himself in peril again when the man who had raised the cry before repeated doggedly that they could not tell how much he knew….

“Take him away,” said the old man suddenly. “You take him — you two” — and he pointed twice. “Keep him while we talk — till I send for you.”

At least it was reprieve and Theodore knew himself in safety, if only for a passing moment. For their own comfort, if not for his, his guards escorted him to the fire in the open, where they crouched down, stolid and watchful, Theodore between them — exhausted by emotion and flaccid both in body and mind…. There was a curious relief in the knowledge that he had shot his last bolt and could do nothing more to save himself; that whatever befell him — release or swift death — was a happening beyond his control. No effort more was required of him and all that he could do was to wait.

He waited dumbly, in the end almost drowsily, with his head bent forward on his knees.

After minutes, or hours, a hand was laid on his shoulder and shook it; he raised his eyes stupidly, saw his guards already on their feet and with them a third man — sent, doubtless, with orders to summon them. He rose, knowing that a decision had been made, one way or another, but still oddly numb and unmoved…. The two men with him thrust a way into the crowded little room, elbowing their fellows aside till they had pushed and dragged their charge to the neighbourhood of the fireplace and set him face to face with his judge. As they fell back a pace or two — as far as the crowding of the room allowed — someone again lit a branch at the fire and held it up that the light might fall upon the prisoner.

To Theodore the action brought with it a conviction that his sentence was death and his manner of receiving it a diversion for the eyes of the beholders…. The old man was waiting, intent, with his chin on his hand, that he might lengthen the diversion by lengthening the suspense of the prisoner….

When he spoke at last his words were a surprise — instead of a judgment, came a query.

“What were you?” he asked suddenly; and, at the unexpected, irrelevant question, Theodore, still numb, hesitated — then repeated mechanically, “What was I?”

“In the days before the Ruin — what were you? What sort of work did you do? How did you earn your living?”

He knew that, pointless as the question seemed, there was something that mattered behind it; his face was being searched for the truth and the ring of listeners had ceased to jostle and were waiting in silence for the answer.

“I — I was a clerk,” he stammered, bewildered.

“A clerk,” the other repeated — as it seemed to Theodore suspiciously. “There were a great many different kinds of clerks — they did all sorts of things. What did you do?”

“I was a civil servant,” Theodore explained. “A clerk in the Distribution Office — in Whitehall.”

“That means you wrote letters — did accounts?”

“Yes. Wrote letters, principally… and filed them. And drew up reports….”

The question sent him back through the ages. In the eye of his mind he saw his daily office — the shelves, the rows of files, interminable files — and himself, neat-suited, clean-fingered, at his desk. Neat-suited, clean-fingered and idling through a short day’s work; with Cassidy’s head at the desk by the window — and Birnbaum, the Jew boy, who always wore a buttonhole…. He brought himself back with an effort, from then to now — from the seemly remembrance of the life bureaucratic to a crowd of evil-smelling savages….

“You were always that — just a clerk? You have never had any other way of earning a living?”… And again he knew that the answer mattered, that his “No!” was listened for intently.

“You weren’t ever an engineer?” the old man persisted. “Or a scientific man of any kind?”

“No,” Theodore repeated, “I have never had anything to do with either engineering or science. When I left the University I went straight into the Distribution Office and I stayed there till the war.”

“University!” The word (so it seemed to him) was snatched at. “You’re a college man?”

“I was at Oxford,” Theodore told him.

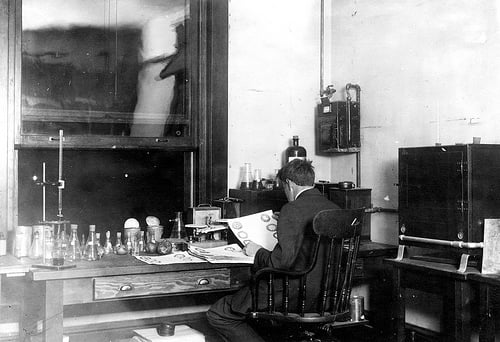

“A college man — then they must have taught you science. They always taught it at colleges. Chemistry and that sort of thing — you know chemistry?”

In the crowd was a sudden thrill that was almost murmur; and Theodore hesitated before he answered, his tongue grown dry in his mouth…. Were these people, these outcasts from civilization, hoping to find in him a guide and saviour who should lighten the burden of their barbarism by leading them back to the science which had once been a part of their daily life, but of which they had no practical knowledge?… If so, how far was it safe to lie to them? and how far, having lied, could he disguise his dire ignorance of processes mechanical and chemical? What would they hope from him, expect in the way of achievement and proof?… Miracles, perhaps — sheer blank impossibilities….

“Science — they taught it you,” the old man was reiterating, insisting.

“Yes, they taught it me,” he stammered, delaying his answer. “That is to say, I used to attend lectures….”

“Then you know chemistry? Gases and how to make them?… And machines — do you know about machines? You could help us with machines — tell us how to make one?”

The dirty old face peered up at him, waiting for his “Yes”; and he knew the other faces that he could not see were peering from the shadow with the same odd, sinister eagerness. All waiting, expectant…. The temptation to lie was overwhelming and what held him back was no scruple of conscience but the brute impossibility of making good his claim to a knowledge he did not possess. The utter ignorance betrayed by the form of the old man’s speech — “You know chemistry — do you know about machines?” — would make no allowance for the difficulty of applying knowledge and see no difference between theory and instant practice…. In his hopelessness he gave them the truth and the truth only.

“I have told you already I am not an engineer — I have never had any training in mechanics. As for chemistry — I had to attend lectures at school and college. But that was all — I never really studied it and I’m afraid I remember very little — almost nothing that would be of any practical use to you…. I don’t know what you want but, whatever it is, it would need some sort of apparatus — a chemist has to have his tools like other men. Even if I were a trained chemist I should need those — even if I were a trained chemist I couldn’t separate gases with my bare hands. For that sort of thing you need a laboratory — a workshop — the proper appliances…. I’ll work for you in any way that’s possible — any way — but you mustn’t expect impossibilities, chemistry and mechanics from a man who hasn’t been trained in them…. And why should you expect me to do what you can’t do yourselves — why should you? Is it fair?….”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.