Lord of Light

By:

July 3, 2013

According to its author, the starting impulse for the 1967 novel Lord of Light was a silly play on words – a joke that speaks not at all to the book’s larger concerns, and which, when it does appear in chapter 2, finds our attention like a pimple on the end of an adolescent’s nose. What the joke does speak to, however, is the unabashed and wise-ass humanity that informs Roger Zelazny’s book about gods and demons, enlightenment and immortality.

These days we take its scenario for granted: a spaceship, The Star of India, fleeing the destroyed Earth, finds a planet filled with hostile life. Over generations, the passengers harness technology – neurosurgery, mutation, bioengineering – to develop mental skills and physical abilities that come to resemble, and then are explicitly mapped upon, figures in the Hindu pantheon. Over generations because their other technological plus is an ability to transfer a person’s identity – atman – from one body to its tank-grown replacement. In time the descendants of the original crew have spread across the planet, while their still-living ancestors, countless bodies later, abide in a Celestial City of high-tech splendor, ruled by a heavily-weaponized Trimurti whose policies suppress science amongst their progeny to an easily controlled medieval level.

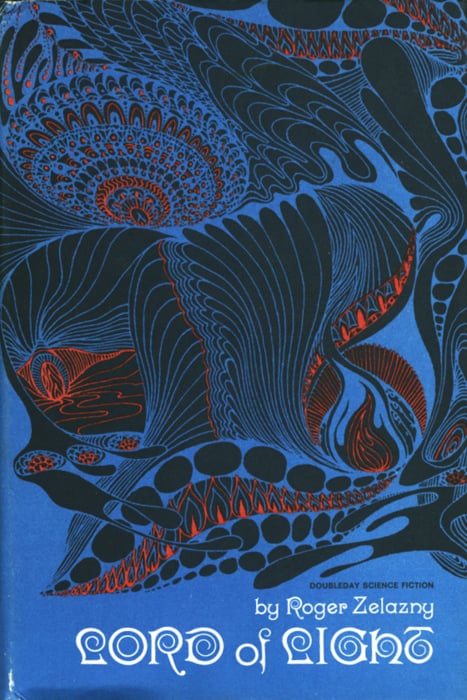

The plot of the book is simple enough as well: an original crewman, Sam, decides to fight the hierarchy of heaven, employing Buddhist teachings, a talent for “electrodirection,” and some shrewd alliances, most notably with Yama, the God of Death. What’s important is how Zelazny, because he’s writing about people, never loses sight of the frailties behind this grand façade – the kinked reasoning beneath every desire for godhead. He writes with humor and compassion about anger and lust, and the entitlement that so swiftly twins itself to power. This light touch shows in jokes like his starting pun, but also in romantic descriptions that remind you, with the same warm feeling one gets looking at the cover of Disraeli Gears, that yes, this was written in 1967. But Zelazny’s own sensibility, his groove, is much more beat. He’s into science, and poetry, like he’s into fencing. He delights in sinking in, whether to track the realpolitik of religion, the impermanence of love, or the granularity of a duel.

More than this, as well as this, Lord of Light, like pretty much everything Zelazny wrote, is also a tightly-plotted, page-turning kick in the pants. Irreverent and reverent, poetic and profane, routinely ingenious. Lord of Light is a book dedicated to dragging all wizards out from behind their curtains, but it isn’t cynical. Nor is it optimistic, per se – any hope for the future is twice tempered, by loss and by betrayal. But still, the book insists, across the fragile margins of its world, on the possibility of insight, perhaps even enlightenment, from the humblest or most corrupted life.