Theodore Savage (17)

By:

July 1, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the seventeenth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

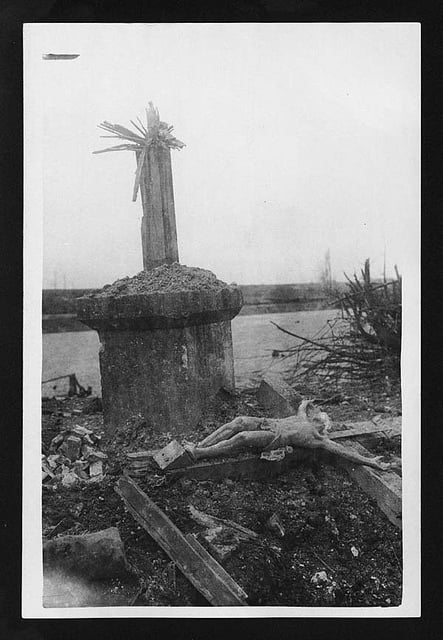

So, in pleasant company, he trudged until well after midday; when, perhaps discouraged by the beginnings of bodily weariness, perhaps affected by the sight of the stark village street — his unreasonable hopefulness passed and anxiety returned. He grew conscious, suddenly and acutely, of his actual surroundings; of silence, of the waste he had trodden, of the desolation about him, of the unknown loneliness ahead. That above all — the indefinite, on-stretching loneliness. He hurried through the dumb street nervously, listening to his own footsteps — the beat and the crunch of them on a frozen road, their echo against deserted walls; and at the end of the village he turned with relief into the road he had marked on his previous visit, the road that turned to run by the stream a few yards beyond the bridge. It wound dismally into a scorched little wood — not one live shoot in it, a cemetery of poisoned trees; then on, still keeping fairly close to the stream, through the same long waste patched with grass and spreading weed. The road, though it narrowed and was overgrown and crumbling in places, was easy enough to follow for the first few hours, but he sought in vain for traces of its recent use. There was no sign of man or the works of man in use; the only token of his presence were, now and again, a fire-blackened cottage, a jumble of rusted, twisted ironwork or a skeleton with rank grass thrusting through the whitened ribs. When the river rounded a turn in the hills, the prospect before him was even as the prospect behind; a waste and silence where corn had once grown and cattle pastured.

As the day wore on the heavy silence was irksome and more than irksome. It was broken only by the sound of his footsteps, the whisper of grass in a faint little wind and now and again — more rarely — by the chirp and flutter of a bird. Long before dusk he began to fear the night, to think, with something like craving, of the shelter and the fire and the woman beside it — that was home; the thought of hours of darkness spent alone amongst the whitened bones of men and the blackened carcases of trees loomed before him as a growing threat. He pushed on doggedly, refusing himself the spell of rest he needed, in the hope that when night came down on him he might have left the drear wilderness behind.

It was a hope doomed to disappointment; the fall of the early December evening found him still in the unending waste, and when the dusk thickened into darkness he camped, perforce, near the edge of the river in the lee of a broken wall. The branches of a dead tree near by afforded him fuel for the fire that he kindled with difficulty with the aid of a rough contrivance of flint and steel; and as he crouched by the blaze and ate his evening ration he scanned the night sky with anxious and observant eyes. So far the weather had been clear and dry, but he realized the peril of a break in it, of a snowstorm in shelterless country…. If to-morrow were only as to-day — if the waste stretched on without trace of man or sign of ending — what then? Would it be wise or safe to push on for yet another day — leaving home yet further behind him? For the journey back the waste must be recrossed, in whatever weather the winter pleased to send him; traversed by day and camped on by night, in hail, in rain, in snow… The thought gave him pause since exposure might well mean death — and to more than himself.

He slept little and brokenly, rousing at intervals with a shiver as the fire died down for want of tendance; and was on his feet with the first grey of morning, trudging forward with fear at his heels. It was a fear that pressed close on them with the passing of long lonely hours; still wintry hours wherethrough he strained his eyes for a curl of smoke or a movement on the outspread landscape…. The day was yesterday over again; the same pale sky, the dull swollen river that led him on, and the endless waste of shallow valley; and when night came down again he knew only this — a clump of hills that had been distant was nearer, and he was a day’s tramp further on his way. He settled at sundown in a copse of withered trees which afforded him plentiful firing if little else in the way of shelter from the night; and having kindled a blaze he warmed his food, ate and slept — too weary to lie awake and brood.

He had not slept long — for the logs still glowed redly and flickered — when he started into wakefulness that was instant, complete and alert. Something — he knew it — had stirred in the silence and roused him; he sat up, peered round and listened with the watchful terror instinctive in the hunted, be the hunted beast or man. For a moment he peered round, seeing nothing, hearing nothing but the whisper of the fire and the beating of his own heart… then, in the blackness, two points caught the firelight — eyes!… Eyes unmistakable, that glowed and were fixed on him….

He stiffened and stared at them, open-mouthed; then, as a sudden flicker of the dying flame showed the outline of a bearded human face, he choked out something inarticulate and made to scramble to his feet. Swift as was the movement he was still on a knee when someone from behind leaped on him and pinned both arms to his sides…. As he wrestled instinctively other hands grasped him; he was the held and helpless captive of three or four who clutched him by throat, wrist and shoulder…. By that token he was back among men.

When they had him down and helpless at their feet, a dry branch was thrust into the embers and, as it flamed, held aloft that the light might fall upon his face. To him it revealed the half-dozen faces that looked down at him — weatherworn, hairy and browned with dirt, the eyes, for the moment, aglow with the pleasure of the hunter who has tracked and snared his prey. They held their prey and gazed at it, as they would have gazed at and measured a beast they had roped into helplessness. Satisfaction at the capture shone in their faces; the natural and grim satisfaction of him who has met and mastered his natural enemy…. That, for the moment, was all; they had met with a man and overcome him. Curiosity, even, would come later. Theodore, after his first instinctive lunge and struggle, lay motionless — flaccid and beaten; understanding in a flash that was agony that men were still what they had been when he fled from them into the wilderness — beast-men who stalked and tore each other. In the torchlight the dirty, coarse faces were savage and animal; the eyes that glowered down at him had the staring intentness of the animal…. He expected death from a blow or a knife-thrust, and closed his eyes that he might not see it coming; and instead saw, as plainly as with bodily eyes, a vision of Ada by the camp fire, sitting hunched and listening for his footstep. Listening for it, staring at the dreadful darkness — through night after dreadful night…. In a torment of pity for his mate and her child he stammered an appeal for his life.

“For God’s sake —I wasn’t doing any harm. If you’ll only listen — my wife… All that I want…”

If they were moved they did not show it, and it may be they were not moved — having lived, themselves, through so much of misery and bodily terror that they had ceased to respond to its familiar workings in others. Fear and the expression of fear to them were usual and normal, and they listened undisturbed while he tried to stammer out his pleading. Not only undisturbed but apparently uninterested; while he spoke one was twisting the knife from his belt and another taking stock of the contents of his food-bag; and he had only gasped out a broken sentence or two when the holder of the torch — as it seemed the leader — cut him short with “Are you alone?”… Once satisfied on that head he listened no more, but dropped the torch back on to the fire and kicked apart the dying embers. The action was apparently a sign to move on; the hands that gripped Theodore dragged him to his feet and urged him forward; and, with a captor holding to either arm, he stumbled out of the clump of stark trees into the open desert — now whitened by a moon at the full.

There was little enough talk amongst his captors as, for more than two hours, they thrust and guided him along; such muttered talk as there was, was not addressed to their prisoner and he judged it best to be silent. It was — so he guessed — the red shine of his fire that had drawn attention to his presence; and, the fear of instant death removed, he drew courage from the thought that the men who held and hurried him must be dwellers in some near-by village. Once he had reached it and been given opportunity to tell his story and explain his presence, they would cease to hold him in suspicion — so he comforted himself as they strode through the wilderness in silence.

After an hour of steady tramping they turned inland sharply from the river till a mile or so brought them to broken, rising ground and a smaller stream babbling from the hills. They followed its course, for the most part steadily uphill, and, at the end of another mile, the scorched black stumps gave place to trees uninjured — spruce firs in their solemn foliage and oaks with their tracery of twigs. A copse, then a stretch of short turf and the spring of heather underfoot; then down, to more trees growing thickly in a hollow — and through them a glow that was lire. Then figures that moved, silhouetted, in and out of the glow and across it; an open space in the midst of the trees and hut-shapes, half-seen and half-guessed at, in the mingling of flicker and deep shadow…. Out of the darkness a dog yapped his warning — then another — and at the sound Theodore thrilled and quivered as at a voice from another world. Now and again, while he lived in his wilderness, he had heard the sharp and familiar yelp of some masterless dog, run wild and hunting for his food; but the dog that lived with man and guarded him was an adjunct of civilization!

The warning had roused the little community before the newcomers emerged from the shadow of the trees; and as they entered the clearing and were visible, men hurried towards them, shouting questions. Theodore found himself the centre of a staring, hustling group — which urged him to the fire that it might see him the better, which questioned his guards while it stared at him…. Here, too, was the strange aloofness that refrained from direct address; he was gazed at, stolidly or eagerly, taken stock of as if he were a beast, and his guards explained how and where they had found him, as if he himself were incapable of speech, as they might have spoken of the finding of a dog that had strayed from its owner. Perhaps it was uneasiness that held him silent, or perhaps he adapted himself unconsciously to the general attitude; at any rate — as he remembered afterwards — he made no effort to speak.

The men and women who crowded round him, staring and murmuring, were in number, perhaps, between thirty and forty; women with matted hair straggling and men unshorn, their garments, like his own, a patchwork of oddments and all of them uncouth and unclean. One woman, he noted, had a child at her half-naked breast; a dirty little nursling but a few months old, its downy pate crusted with scabs. He stared at it, wondering as to the manner of its birth — the mother returning his scrutiny with open-mouthed interest until shouldered aside without ceremony by a man whom Theodore recognized for the leader of his band of captors. When they reached the shadow of the clump of trees he had stridden ahead and vanished, presumably to report and seek orders from some higher authority; and now, at a word from him, Theodore was again jerked forward by his guards and, with the crowd breaking and tailing behind him, was led some fifty or sixty yards further to where, on the edge of the clump of trees, stood a building, a tumbledown cottage. The moon without and a fire within showed broken panes stuffed with moss and a thatched roof falling to decay; inside the atmosphere was foul and stale, and heavy with the heat of a blazing wood fire which alone gave light to the room.

By the fire, seated on a backless kitchen chair, sat a man, grey of head and bent of shoulder; but even in the firelight his eyes were keen and steely — large bright-blue eyes that shone under thick grey eyebrows. His face, with its bright, stubborn eyes and tight mouth, was — for all its dirt — the face of a man who gave orders; and it did not escape the prisoner that the others — the crowd that was thrusting and packing itself into the room — were one and all silent till he spoke.

“Come nearer,” he said — and on the word, Theodore was pushed close to him. “Let him go”— and Theodore was loosed. Someone, at a sign, lit a stick from the heap beside the fire and held it aloft; and for a moment, till it flared itself out, there was silence, while the old man peered at the stranger. With the sudden light the hustling and jostling ceased, and the crowd, like Theodore, waited on the old man’s words.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.