Theodore Savage (16)

By:

June 24, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the sixteenth installment of our serialization of Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (also known as Lest Ye Die). New installments will appear each Monday for 25 weeks.

When war breaks out in Europe — war which aims successfully to displace entire populations — British civilization collapses utterly and overnight. The ironically named Theodore Savage, an educated and dissatisfied idler, must learn to survive by his wits in the new England, where 20th-century science, technology, and culture are regarded with superstitious awe and terror.

The book — by a writer best known today for her suffragist plays, treatises, and activism — was published in 1922. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish it in a gorgeous paperback edition, with an Introduction by Gary Panter.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25

It was when the days were nearly at their shortest that the round and tenor of his life was broken by the shock of a disturbing knowledge. Trudging homewards toward sunset on a mild December evening, he came upon his wife sitting groaning in the path; she had been on her way to the stream for water when a paroxysm of sickness overtook her. Since the days of starvation he had never seen her ill and the violence of the paroxysm frightened him; when it was over and she leaned on him exhausted as he led her back to their camping-place, he questioned her anxiously as to what had upset her — had she pain, had she eaten anything unwholesome or unusual? She shook her head silently in answer to his queries till he sat her down by the fire ; then, as he knelt beside her, stirring the logs into a blaze, she caught his arm suddenly and pressed her face tightly against it. “Ow, Theodore, I’m going to ’ave a baiby!” “What?” he said. “What?” — and stared at her, his mouth wide open…. Perhaps she was hurt or disappointed at his manner of taking the news; at any rate she burst into floods of noisy weeping, rocking herself backwards and forwards and hiding her face in her hands. He did his best to soothe her, stroking her hair and encircling her shoulders with an arm; seeking vainly for the words that would stay her tears, for something that would hearten and uplift her. He supposed she was frightened — more frightened even than he was; his first bewildered thought, when he heard the news, had been ‘What, in God’s name, shall we do?’

He drew her head to his shoulder, muttering “There, there,” as one would to a child, till her noisy demonstrative sobbing died down to an intermittent whimper; and when she was quieted she volunteered an answer to the question his mind had been forming. She thought it would be somewhere about five months — but it mightn’t be so long, she couldn’t be sure. She didn’t know enough about it to be sure — how could she, seeing as it was her first?… She had been afraid for ever so long now — weeks and weeks — but she’d gone on hoping and that was why she hadn’t said anything about it before. Now there wasn’t any doubt — she wondered he hadn’t seen for himself… and she clung to him again with another burst of noisy weeping.

“But,” he ventured uncertainly, reaching out after comfort, “when it’s over — and there’s the baby — you’ll be glad, won’t you?”

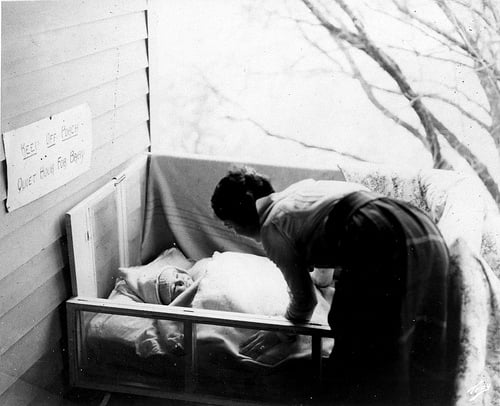

His appeal to the maternal instinct had no immediate success. Ada protested with yet noisier crying that she was bound to die when the baby came, so how could she possibly be glad? It was all very well for him to talk like that — he didn’t have to go through it! Lots of women died, even when they had proper ’orspitals and doctors and nurses….

He listened helplessly, not knowing how to take her; until, common sense coming to his aid, he fell back on the certainty that exhausting, hysterical weeping could by no possibility be good for her, rebuked her with authority for upsetting herself and insisted on immediate self-control. It was well for them both that wifely obedience was already a habit with Ada; by the change in his tone she recognized an order, pulled herself together, rubbed her swollen eyes and even made an effort to help with the preparing of supper — whining a little, now and again, but checking the whine before it had risen to a wail.

She was manifestly cheered by a bowlful of hot stew — whereof, though she pushed it away at first, she finished by eating sufficiently; and, once convinced that the outburst of emotion was over, he petted her, though not too sympathetically, lest he stirred her again to self-pity. She was not particularly responsive to his hesitating suggestions anent the coming joys of maternity; more successful in raising her spirits were his actual encouraging pats and caresses, his assumption of confidence greater than he felt in the neighbourhood of men and women whose hands were not turned against their fellows…. He realized that, as the suspicion of her motherhood grew to a certainty, she had spent long, lonely hours oppressed by sheer physical terror; and he reproached himself for having been carelessly unobservant of a suffering that should long ere this have been plain to him.

He was longing to be alone and to think undistracted; it was a relief to him therefore when, warmed, fed, and exhausted by her crying, she began to nod against his shoulder. He insisted jestingly on immediate bed, patted and pulled at her moss-couch before she lay down, kissed her — whereupon she again cried a little — and sat beside her, listening, till her breathing was even and regular. Once sure that she slept, he crept back to the fire to sit with his chin on his hands; outside was the silence of a still December night, where the only sound was the rush of water and the hiss and snap of burning logs.

With his elbows on his knees and his chin on his hands, he stared into the fire and the future… wondering why it had come as a shock to him — this natural, this almost inevitable consequence of the life he shared with a woman? He found no immediate answer to the question; understanding only that the animal and unreflecting need which had driven them into each other’s arms had coloured their whole sex-relation. They had lived like the animal, without any thought of the future…. Now the civilized man in him demanded that his child should be born of something more than unreasoning lust of the flesh and there stirred in him a craving to reverence the mother of his son…. Ada, flaccid, lazy, infantile of mind, was more, for the moment, than her prosaic, incapable self. A rush of tenderness swept over him — for her and for the little insistent life which might, when its time came, have to struggle into being unaided….

With the thought returned the dread which had flashed into his mind when Ada revealed to him his fatherhood. If their life in hiding were destined to continue — if all men within reach were as those they had fled from, there would come the moment when — he should not know what to do!… He remembered, years ago, in the rooms of a friend, a medical student, how, with prurient youthful curiosity, he had picked up a textbook on midwifery — and sought feverishly to recall what he had read as he fluttered its pages and eyed its startling illustrations.

As had happened sometimes in the first days of loneliness, the immensity of the world overwhelmed him; he sat crouched by his fire, an insect of a man, surrounded by unending distances. An insect of a man, a pigmy, whom nature in her vastness ignored; yet, for all his insignificance, the guardian of life, the keeper of a woman and her child…. They would look to him for sustenance, for guidance and protection; and he, the little man, would fend for them — his mate and his young…. Of a sudden he knew himself close kin to the bird and beast; to the buck-rabbit diving to the burrow where his doe lay cuddled with her soft blind babies; to the round-eyed blackbird with a beakful gathered for the nest…. The loving, anxious, protective life of the winged and furry little fathers — its unconscious sacrifice brought a lump to his throat and the world was less alien and dreadful because peopled with his brethren — the guardians of their mates and their young.

It was clear to him, so soon as he knew of his coming fatherhood, that, in spite of the drawbacks of winter travelling, his long-deferred journey of exploration must be undertaken at once; the companionship of men, and above all of women, was a necessity to be sought at the risk of any peril or hardship. Hence — with misgiving — he broached the subject to Ada next morning; and in the end, with smaller opposition than he had looked for, her lesser fears were mastered by her greater. That the certain future danger of unaided childbirth might be spared her, she consented to the present misery of days and nights of solitude; and together they made preparations for his voyage of discovery in the outside world and her lonely sojourn in the camp.

As he had expected, her first suggestion had been that they should break camp and journey forth together; but he had argued her firmly out of the idea, insisting less on the possible dangers of his journey — which he strove, rather, to disguise from her — than on her own manifest unfitness for exertion and exposure to December weather. Once more the habit of wifely obedience came to his assistance and her own, and she bowed to her overlord’s decision — if tearfully, without temper or sullenness; while, the decision once taken, it was he, and not Ada, who lay wakeful through the night and conjured up visions of possible disaster in his absence. His imagination was quickened by the new, strange knowledge of his responsibility, the protective sense it had awakened; and, lying wide awake in the still of the night, it was not only possible danger to Ada that he dreaded — he was suddenly afraid for himself. If misfortune befell him on his journey into the unknown, it would be more than his own misfortune; on his strength, his luck and well-being depended the life of his woman and her unborn child. If evil befell him and he never came back to them — if he left his bones in the beyond…. At the thought the sweat broke out on his face and he started up shivering on his moss-bed.

He worked through the day at preparations for the morning’s departure which, if simple, demanded thought and time; saw that plentiful provision of food and dry fuel lay ready to his wife’s hand, so that small exertion would be needed for the making of fire and meal. For his own provisioning he filled a bag with cooked fish, chestnuts and the like — store enough to keep him with care for five or six days. All was made ready by nightfall for an early start on the morrow; and he was awake and afoot with the first reddening of a dull December morning. Fearing a breakdown from Ada at the last moment, he had planned to leave her still asleep; but the crackling of a log he had thrown on the embers roused her and she sat up, pushing the tumbled brown hair from her eyes.

“You’re going?” she asked with a catch in her voice; and he avoided her eye as he nodded back “Yes,” and slung his bag over his shoulder.

“Just off,” he told her with blatant cheeriness. “Take care of yourself and have a good breakfast. There’s water in the cookpot — and mind you look after the fire. I’ve put you plenty of logs handy — more than you’ll want till I come back. Good-bye!”

“You might say good-bye properly,” she whimpered after him.

He affected not to hear and strode away whistling; he had purposely tried to make the parting as careless and unemotional as his daily going forth to work. Purposely, therefore, he did not look back until he was too far away to see her face; it was only when the trees were about to hide him that he turned, waved and shouted and saw her lift an arm in reply. She did not shout back — he guessed that she could not — and when the trees hid him he ran for a space, lest the temptation to follow and call him back should master her.

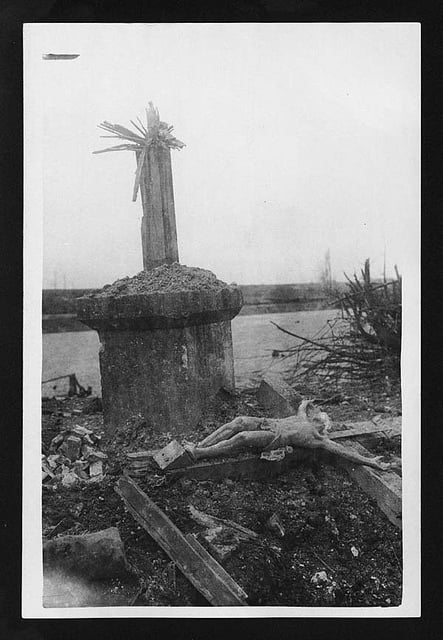

He had planned out his journey often enough during the last few months; considering the drift of the river and lie of the country and attempting to reduce them to map-form on the soil by the aid of a pointed stick. His idea was to make, in the first place, for the silent village which had hitherto been the limit of his voyaging; and thence to follow the road beside the river which in time, very surely, must bring him to the haunts of men. Somewhere on the banks of the river — beyond the tract of devastated ground — must dwell those who drank from its waters and fished in them; who perhaps — now the night of destruction was over and humanity had ceased to tear at and prey upon itself — were rebuilding their civilization and salving their treasures from ruin!… The air, crisp and frosty, set him walking eagerly, and as his body glowed from the swiftness of his pace a pleasurable excitement took hold of him; his sweating fears of the night were forgotten and his brain worked keenly, adventurously. Somewhere, and not far, were men like unto himself, beginning their life and their world anew in communities reviving and hopeful. Even, it might be — (he began to dream dreams) — communities comparatively unscathed; with homes and lands unpoisoned, unshattered, living ordered and orderly lives!… Some such communities the devils of destruction must have spared… If a turn in the valley should reveal to him suddenly a town like the old towns, with men going out and in!

He quickened his pace at the thought and the miles went under him happily. He was no longer alone; even when he entered the long waste of coarse grass and blackened tree that lay around the dead village its dreariness was peopled with his vivid and hopeful imaginings… of a crowd that hustled to hear his story, that questioned and welcomed and was friendly — and led him to a house that was furnished and whole… where were books and good comfort and talk….

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.